As I sit with Eileen Cooper on the roof terrace of the NED hotel looking over the London skyline, large snowflakes swirl outside the plate glass window and we calculate that the first time we sat down together to discuss her work was thirty-three years ago. The circumstances were rather different then. I was a young art critic and poet, a single mother new to London, writing for Time Out. Eileen was an “emerging” artist. She had a gallery in the West End and was getting noticed. Her work was much favoured by women writers for their book covers. I, myself, used a powerful charcoal drawing Carefully (1993) on the front of my first poetry collection, Everything Begins with the Skin. At that first meeting we sat huddled in a bedroom of her south London home that was then being used as a kitchen, while the downstairs was slowly being converted. We talked about art and the struggle to be both mothers of small children and creative women. It’s a long time ago now. But those times shaped who we are. The lives of women, relationships, fertility and sexuality have long been the enduring themes of Eileen Cooper’s very human work.

Born in the Peak District, Derbyshire in 1953, she went, as she says, to an ordinary comprehensive. It was a long journey from there to become the first female Keeper of the Royal Academy Schools since the RA began in 1768. Drawing has always been the basis of her practice. She’s an organic, intuitive artist who discovers things through the process of making, through experimentation in the studio. Her drawings, prints and paintings are peopled with strong, independent women. Often, they are the main nurturers among a cast of men, boys and animals that range from cats to tigers. Monumental and assured, many of her women are nude. Some dance. She’s not interested in the naturalistic but in symbols and implied narratives.

Totemic and wild, her women are closely allied with nature. Halfway between humans and goddesses. In The Two Gardeners (1989) a pair of naked females, painted in bright vermillion, swing from a scroll of vines above their gardening fork and spade, while in Enchantress (2000) a woman covers her face with a mask of leaves like some sort of ecological dance of the Seven Veils. There’s an ecstatic, chthonic quality to her movement, as though she’s just escaped from the Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Primitive, shamanic and atavistic, T.S. Eliot’s clodhopping dancers come to mind: “Leaping though the flames, or joined in circles, /Rustically solemn or in rustic laughter/Lifting heavy feet in clumsy shoes,/ Earth feet, loam feet lifted in country mirth….”

Her figures pulse with energy, part of the matrix of life in which we all find ourselves entwined. They are living, breathing, sensing bodies that draw their sustenance from the soil, from plants and animals. Of late she’s been making sculptures but says she’s happiest working in two dimensions. Her influences are Indian miniatures and mediaeval painting. The German expressionists from Nolde to Kirchner. Picasso and the Fauvists. Like these artists she is a powerful colourist.

Has she always been a feminist? Yes, she answers. But it’s only now, when she looks back on her time as a student in the early 70s at Goldsmiths, that she realises how often she was excluded from core activities. Then she hardly noticed. She just got her head down and worked. She only had male tutors. Though some, like Basil Beattie and Bert Irvin, were supportive of women. When she started teaching she was unusual: both a woman and a figurative painter.

“Networking is so important to success as an artist. But a gap opens up for young women with families.”

Is her work autobiographical? “Not directly”, she answers. But it does “draw from my experience. It’s about movement and balance. About juggling. The figures are contained within a rectangle. I think of it like theatre where I explore issues of creativity, work and family relationships. Networking is so important to success as an artist. But a gap opens up for young women with families. Going to private views is out because that’s children’s tea-time. It’s hard to keep going.”

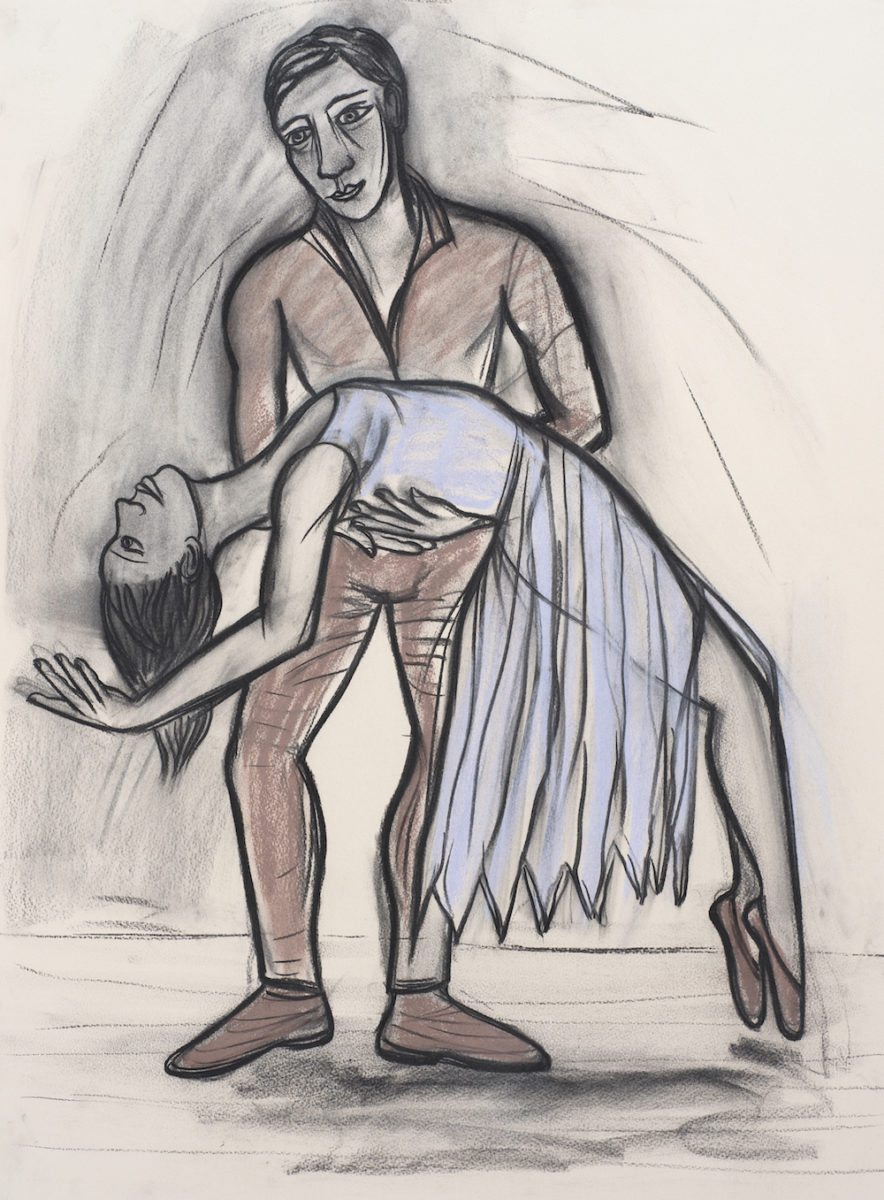

Hear the Wind Cry I, 2017

I ask what she thinks about the current #MeToo campaign and, like many women of our generation, she is ambivalent, feeling that the slogan is too simplistic. “I tend,” she says, “to put the past behind me and live in the present. Class was, in fact, as much an issue for me as being a woman. I didn’t come from a background where people went to art school.” She feels it’s important to help students find their way through a system that’s always favoured the privileged and the male. Even now, she claims, there are far fewer women in major collections than men. “And that,” she says, “is in modern collections, not just historic ones” But, she passionately believes in the value of a liberal arts education, whether or not students go on to be artists, and feels that it’s in danger of being cannibalised. “Education is a thing in itself. It’s not just about qualifications.”

“I try not to take myself too seriously. There’s so much pomposity in the art world.”

And now that she’s handed on the baton of Keeper, I ask, what does she plan to do? She’s lucky, she says. She has the time to take her practice in new directions. As a process-based artist, she likes to work outside her comfort zone, experimenting with new materials and ideas. “I try,” she says, “not to take myself too seriously. There’s so much pomposity in the art world. Of course, in the studio, I’m deadly serious, but I like to take a step back, to help young artists. Education changed my life. I’m proud of my time at the Academy Schools. It’s a centre of excellence.”

- Body Talk 3, 2017

- Centre Stage 2, 2017

And now there’s a new development. She has a gallery in Beirut, Lebanon. Going there has given her fresh ideas. She’s fascinated by the ancient mosaics she’s discovered, experimenting with how she can incorporate them into her work. She likes how, when we walk on them, they connect us to the past, give us a direct route back through time to older civilizations. She’s always trying to improve as an artist but admits there’s probably only so much work inside her. Now, for the first time, she can take things a bit easy. She might take longer on an individual work or spend more time preparing. If she’s working on paper she often draws flat on the table, beginning with a charcoal outline. Other times she’ll work on an easel, changing and experimenting as she goes along, rubbing out with tissue paper and rag, then transforming and rebuilding. Drawing will always be central, but she is working on three new big canvases. And she loves printmaking. The co-operation, the sociability. Working in a team.

Like Paula Rego, who is a decade and a half older, Eileen Cooper shows us the world, after centuries of seeing it through the male gaze, through female eyes. She creates narratives of the collective female experience in a universe peopled by women, their partners and children. Her work is intimate and accessible, concerned above all with how we make sense of our lives as mothers, wives and friends. But it’s also knowing, informed and packed full of influences from Giotto to Matisse, and as much about the process of being an artist—the use of materials, the medium etc—as it is about exploring the experiences and adventures of being a modern woman.

Pause, 2017