Luís Lázaro Matos

Creating environments to immerse yourself within is Luís Lázaro Matos’ gift. With a keen eye for architectural and design details, he conjures everything from the cool breeze of a swimming pool in the south of France to a futuristic alien dystopia, complete with interplanetary satellite dishes. A graduate of Goldsmiths, he harnesses various modes of communication, from set building to zine-making and even music production, to tackle themes as diverse as social media and apocalyptic futures. His latest show at Galeria Madragoa in Lisbon takes us underwater. Suspended in space, it conjures an experience somewhere between the ocean and the cosmos, and is aptly titled Seabed Monsters and Cosmic Rays. Music, lights and the signature wall murals of Lázaro Matos come together to conjure the uncertainty of our current moment through the visual language of liquidity. (Louise Benson)

Alicia Reyes McNamara

The Chicago-born artist celebrates the fallen women of Mexican and Irish mythology in her latest series of paintings. While researching the history of mythology in both countries, she noticed a common symbol of water running through each. She also realised how many of the goddesses in these tales were presented as disgraced, and often punished for the way in which they expressed themselves sexually. Her paintings combine women’s bodies with more animalistic forms, depicting the most intimate bodily spaces being explored, pulled and caressed by aquatic creatures. The colours are joyful, bringing watery tones together with bright pinks and purples. McNamara’s work is on display in a solo show at Niru Ratnam gallery in London until 3 July. (Emily Steer)

- Yukimasa Ida, Mai, 2021 (left). Self Portrait, 2021 (right). Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim

Yukimasa Ida

Japanese painter Yukimasa Ida utilises a dense impasto to create large-scale, heavy-duty canvases that tread a fine line between figuration and abstraction. These thick layers of oils take on the qualities of sculpture, while his bronze ‘heads’ also retain marks that resemble the impact of a forceful palette knife. For his inaugural solo exhibition at Mariane Ibrahim in Chicago (on display from 26 June to 14 August) Ida presents a new body of work that embraces the idiom “ichi-go ichi-e”, a concept that promotes treasuring the expression and unrepeatable nature of a moment. It is a prescient topic for an artist who his finding his own unique language through the experimental possibilities of his materials, while making nods to their position within the canon of art history. (Holly Black)

Gabby Laurent

Falling can be undeniably painful, but there’s still something slapstick, and even liberating, about the act. Gabby Laurent’s new book (out now with Loose Joints) and exhibition (at London’s Webber gallery until 19 June) are all about what happens when we fall (physically and emotionally) and how falling has also become a metaphor, represented in language by so many idiomatic phrases: falling in love, falling unconscious, falling pregnant… Laurent captures the state in a way we can never apprehend, frozen by the camera, making it appear all the more strange and free, an enigmatic dance with fate and gravity, between our bodies and the inevitable. (Charlotte Jansen)

Dickon Drury

The British artist paints intimate, playful and surreal interior scenes loaded with items such as fruit, meat, glasses of wine, cans of food and everyday household items. Despite the lack of living beings in his works (except for the odd fly buzzing around), there is a frenzied energy that brings them to life, carried through in his bright paint choices and packed compositions. He renders the domestic both thrilling and overwhelming. This intensity takes on new pertinence in light of the last year, as many people have spent vast amounts of time indoors, viewing the same domestic spaces day after day. His recent show at Kendall Koppe in Glasgow introduced the laptop computer screen to many of his paintings, offering an enticing window into a world experienced from afar. (Emily Steer)

- Sophie Vallance Cantor, Dress the Part - Douglas, Squats in the Studio, Dress the Part - Naina (left to right), all 2021. Courtesy the artist

Sophie Vallance Cantor

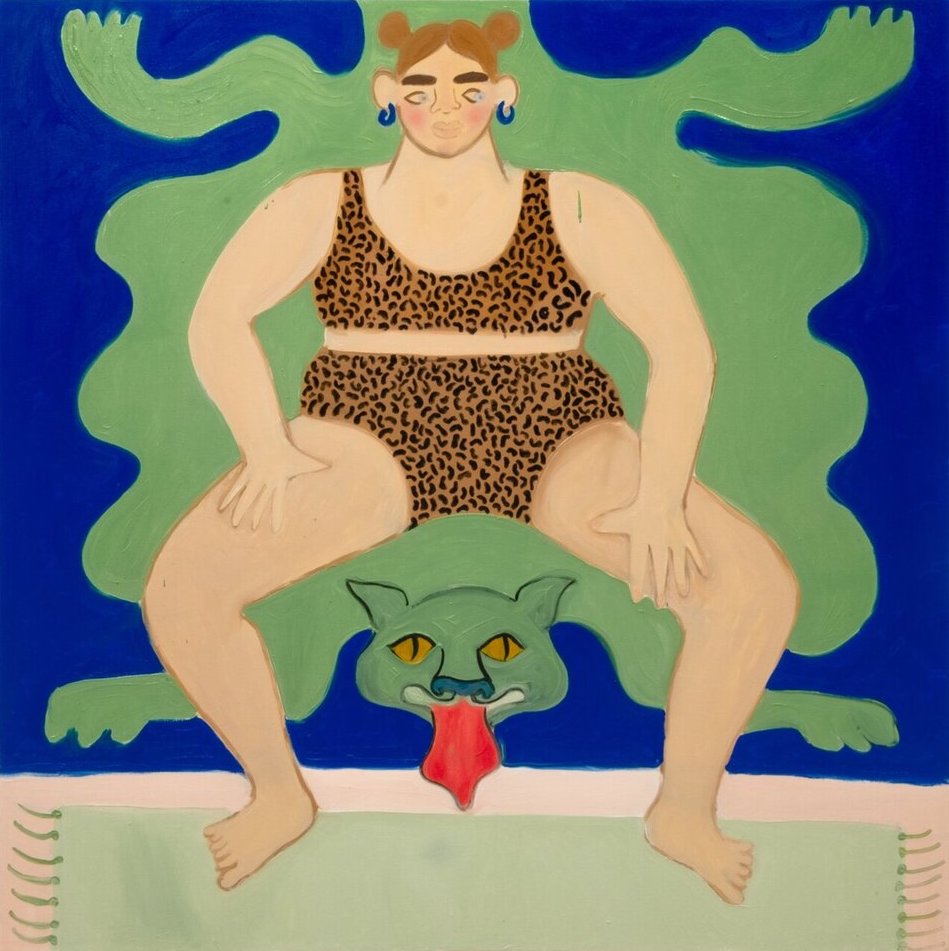

The people who populate the paintings of Sophie Vallance Cantor exist in a world that combines the trappings of contemporary life with the wild roar of the animal kingdom. Domestic cats morph into tigers and panthers, eyes glittering hungrily, while their human accomplices crouch, dance and preen themselves for an unseen audience. A recent graduate of Camberwell College of Arts, the Glasgow-based artist is firmly of the Instagram age, where the line between public and private is frequently blurred. She participated in London Gallery Weekend this June, in a group exhibition staged by Guts Gallery and hosted by Sadie Coles. A further solo show with Guts Gallery is scheduled for 2021, followed by an outing at Kogan Amaro in Sao Paulo. (Louise Benson)

Mame-Diarra Niang

“I have come to think of the self as a territory made of well-curated memories and erasures”, says artist Mame-Diarra Niang, whose beguiling series Léthé reverses the purpose of the photograph. Rather than creating a totem of the past, they constitute a deliberate erasure that forces us to forget. How might our sense of self evolve if we were not constantly looking back through the rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia at what we once were? The experience of looking at Léthé (now showing at Stevenson gallery’s online viewing room) is a frustrating one for a viewer obsessed with visual information. It represents an experiment with the push-pull relationship between photography and knowledge, the picture and the ability to possess time. (Charlotte Jansen)