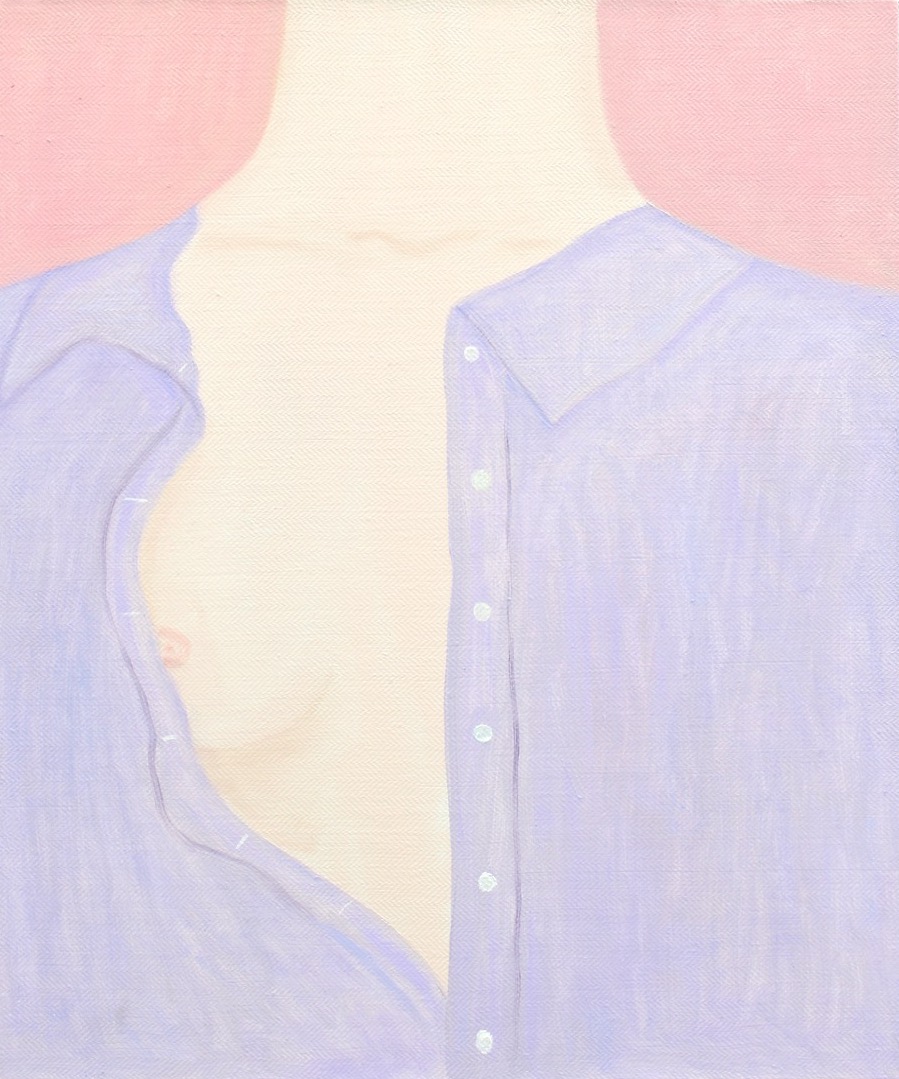

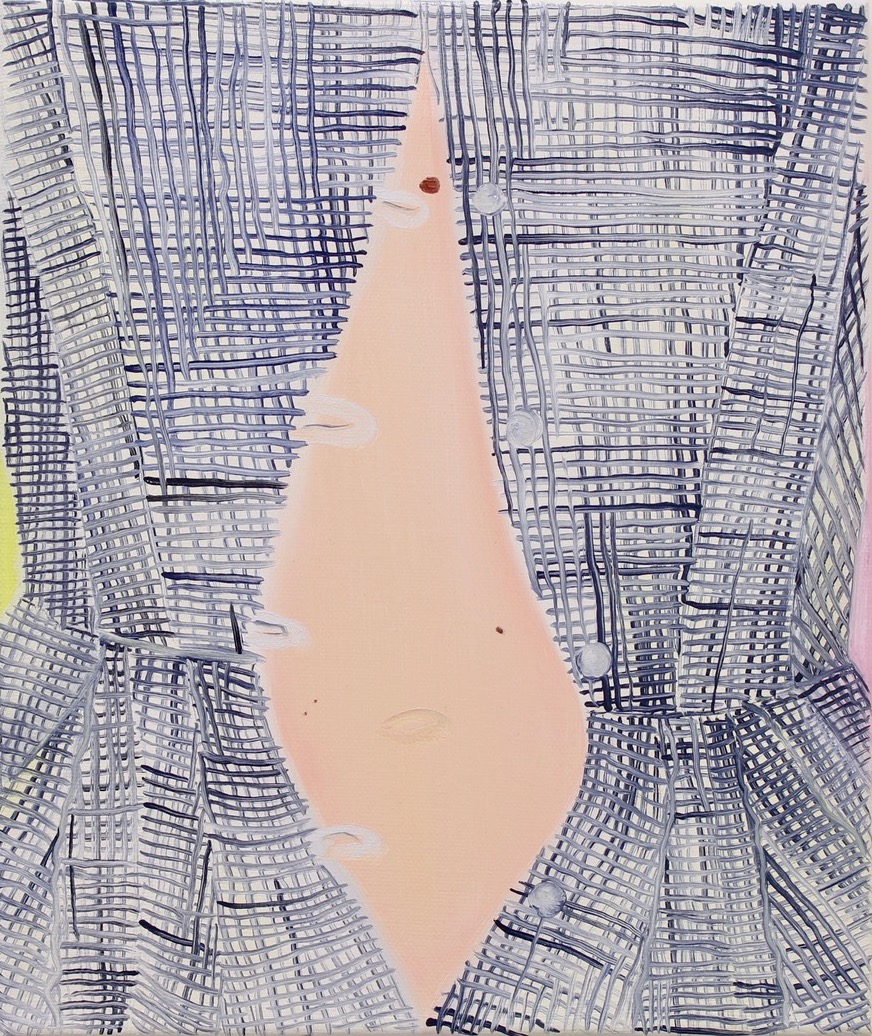

Intimacy and introspection come together in the work of Ellie MacGarry. Her paintings frequently feature tight crops of skin, hair and/or nails, focusing in on the parts of our body that are endlessly renewed. She is interested in the ongoing personal transformation that we each experience, and she emphasizes the many guises that we wear through the gradual stripping away of these layers. Buttons and ribbons come undone, and a casual nip-slip becomes full-frontal nudity.

MacGarry, who recently completed an MFA at the Slade School of Fine Art, also works with ceramics to extend the world of her paintings; combs thick with hair or scattered nail clippings take on a surreal tone when awkwardly rendered in clay. A plate of tomato pasta takes on a strangely hairy quality in one painting, while in others pubic hair peeps out of garments and hemlines, as humorous as it is uncanny.

What is hidden and what is exposed is often central to your paintings, looking closely at garments and how they relate to the naked body beneath. Why do you often choose to focus on the relationship between these elements?

I think it functions in different ways in different paintings. At times I am really interested in the idea of assertive undressing, that the cloth hasn’t just fallen away but that the person has allowed it, and is offering this portion of themselves to you freely. In other works I think of it more as an unravelling; unbuttoned and undone after a long day, shifting from your public body to your private body.

Despite its negative or self-indulgent connotations I really love the expression “navel gazing”; I like to think of it as looking into our bodies in order to get to know ourselves better or to feel closer to ourselves. There’s a sense of tender introspection in being alone with our bodies; it’s an intimate and complex relationship.

This motif of undressing also functions as a metaphor for the general feeling of exposure we might feel day-to-day—exposing ourselves through what we say (and don’t say), what we reveal to others and what we want to keep to ourselves. Clothes give us a lot of choice about how we present ourselves to others, but when they fall away we are just left with what’s underneath: our bare state.

“There’s a sense of tender introspection in being alone with our bodies; it’s an intimate and complex relationship”

Hair is another common motif in your work, suggestive of everything from childhood trips to the hairdressers to the private eroticism of pubic hair. What interests you particularly about hair?

I think what really interests me is less about hair itself and more about these moments of potential transformation, of the shedding of old, of the intimate closeness with someone you have only just met—their fingers on your neck, of being confronted with your own reflection for longer than you might like. There is such a duality of fear and excitement at the prospect of leaving as someone different to when you entered.

The first painting I made of pubic hair is called Fear of Flying Low, which stemmed from imagining an undone fly occurring while for some reason the person wasn’t wearing any underwear. It’s quite a large painting so it becomes abstract in a way: two areas of paint—curling brown lines and smooth blue fabric as contrasting zones of inside and outside.

I struggle to relate to the hairless bodies that have been represented throughout art history, and that are still the dominant representation (of women particularly) in the media today. I have always been really interested in masks and wigs so the merkin paintings stemmed from a fascination in the discovery of these pubic wigs—they are kind of ridiculous but there is something fun and humorous about them. They veer into the carnivalesque of dress-up, blurring lines between human and animal, real and fake. They both reveal and conceal.

You also work with ceramics. How do you incorporate these alongside your paintings into a wider practice, and what are the positives and negatives of each medium?

I make the ceramics in the studio while I am making the paintings and, although I don’t plan them or set out for them to have a direct relationship with a particular painting, there often ends up being an interesting partnership between them. They all seem to inhabit the same world. The ceramics explore similar ideas of self-consciousness; they tend to be slightly embarrassing or tired objects which are a little too well-used, so are not necessarily something you would like the world to see.

I find working with clay very freeing and almost therapeutic and I enjoy experimenting with it. The ceramic brushes came into being when I started pushing small lumps of clay through some wire mesh; the extruded pieces this action created were so bristle-like that I attached them to handles of long, smooth pieces of clay. There is something wonderful about working a piece of clay and being able to give up on it and re-form it back into a ball again—this is a feeling I can never get with a painting. Even if I wipe something off I am really aware of the lingering presence of the past image, it’s never quite the tabula rasa I would like it to be.

Something I love about both paint and clay is that you can make something really quite quickly which completely surprises you—there is an unbelievably open-ended potential in these materials.

The framing and crops in your work are notable for the unusual views and angles that they offer on the women who you depict. What influences these decisions when composing your paintings and choosing what to leave in and what to leave out?

I am really interested in the economy of means when it comes to making artworks—thinking about what is essential and what can be left out. I find there is a directness in the simplicity of the works that this kind of editing process results in. I also like that you can suggest the presence of a body without there being one there, like in my painting Puttanesca.

I have always been fascinated by framing devices in painting; by cropping something at a point of continuation it allows for the imagination of the viewer to expand beyond the constraints of the painting. But the cropping is also a way of emphasizing; it’s a way of asserting the importance of a particular singular moment. I love Italian renaissance painters like Piero della Francesca and Uccello but, when I look at them, there are so many amazing details that I would just love to see in isolation with none of the surrounding elements to distract me. So, in a way, I think this is what I am doing—for myself and for the viewer—in my work.

“I struggle to relate to the hairless bodies that have been represented throughout art history, and that are still the dominant representation (of women particularly) in the media today”

Who are the women in your paintings, and how do you relate to them?

I actually see gender to be quite fluid in my paintings, but there is certainly an element of self-portrait in them—in some cases more in terms of sensation than appearance. I see them as a vehicle to explore a sense of self, to explore gender and the intimate and shifting ways we relate to our bodies. I like Claude Cahun’s attitude towards the self-portrait—although her photographs almost always featured her, they are not necessarily autobiographical but are a “mise en scène” in which she used her body and image as a tool to explore ideas about identity.