It takes a deft, smart and very witty artist to simultaneously address grave and complex issues—globalisation, information networks, climate crisis and the precariousness of employment—with an approach that is democratic, accessible and genuinely funny. It takes an even wittier one to do so with potatoes. It was the humble spud that led me to the work of Swedish-born, Denmark based Emilia Bergmark, whose

Potato The Great works centre on the tuber that was awarded second place in the 2019 Harrogate Giant Vegetable Competition.

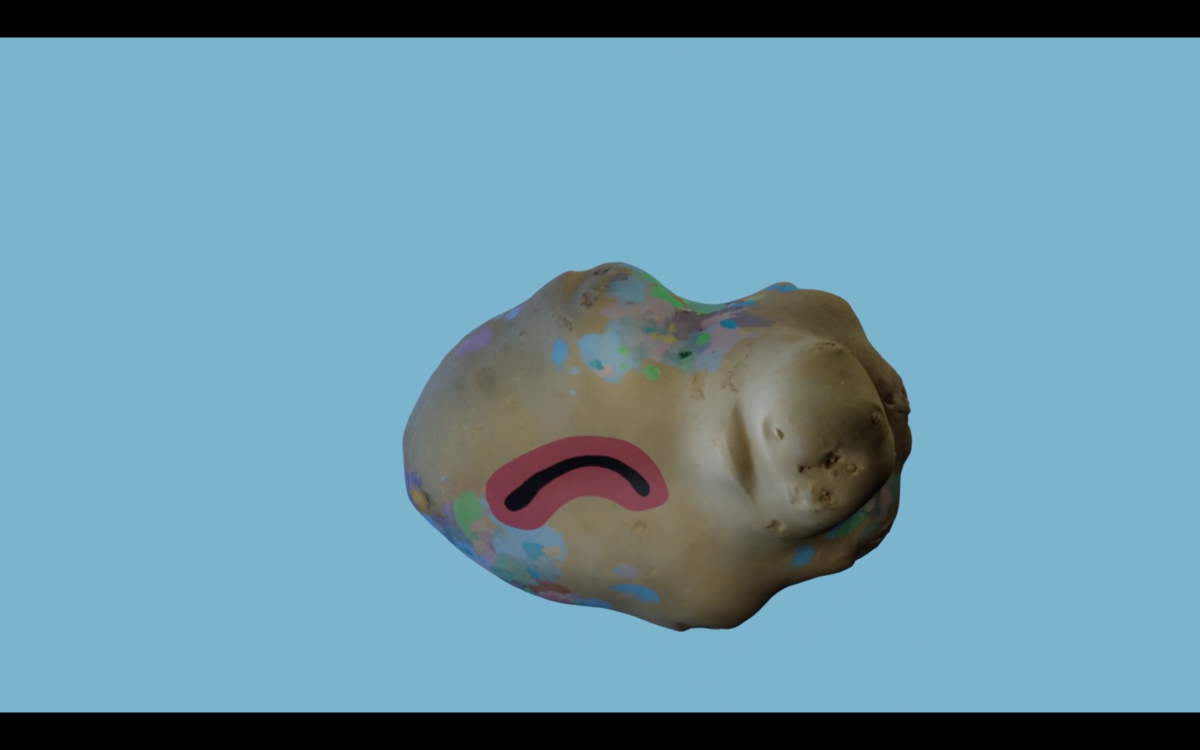

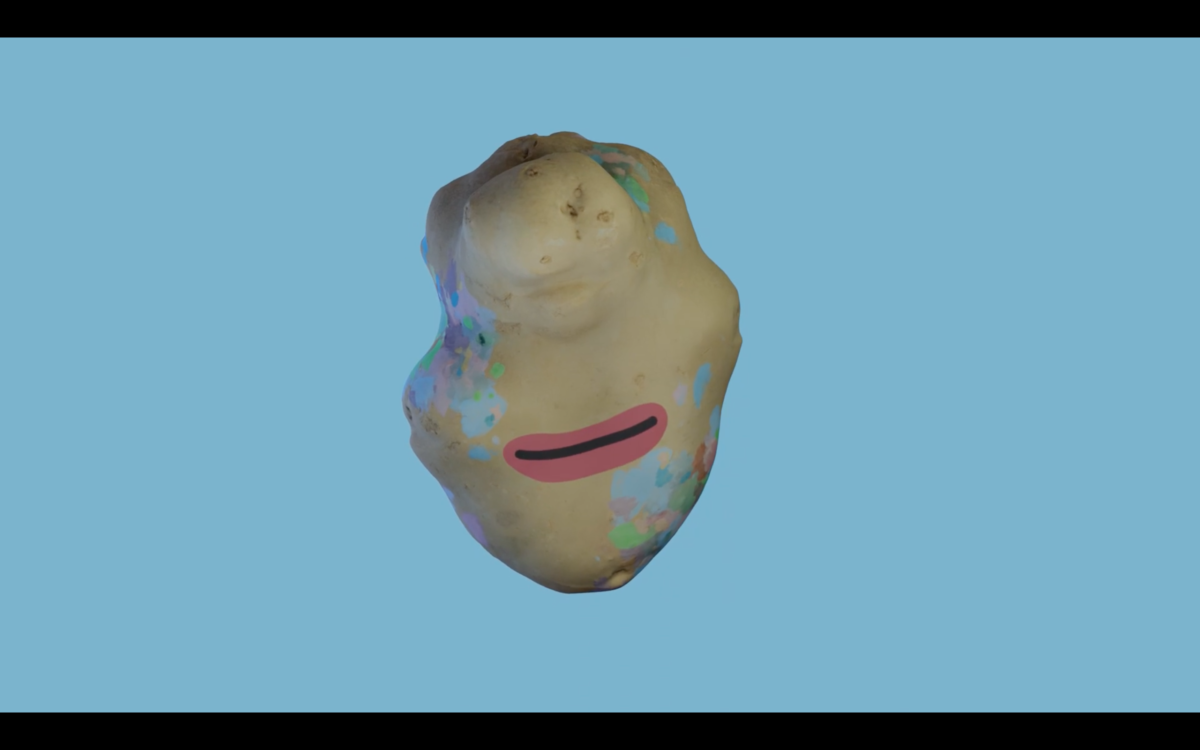

Seeing the works online, I’d assumed this was a sort of wry Instagram-friendly found-object prank; perhaps she’d just daubed some paint on a potato and popped it on a plinth. But no: she had tracked down the actual second-prize winner (a potato as large as her face, which her process shots prove) and created a series of new casts of its exact likeness, which also appeared in a beautifully bizarre moving image piece.

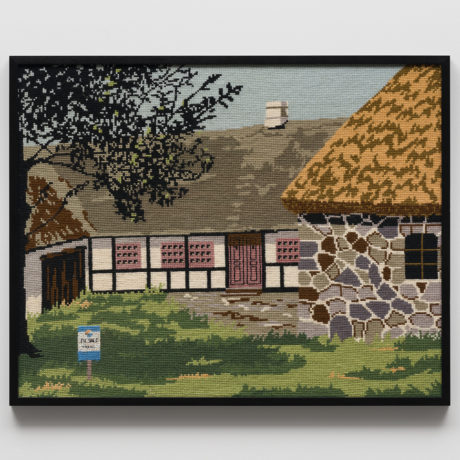

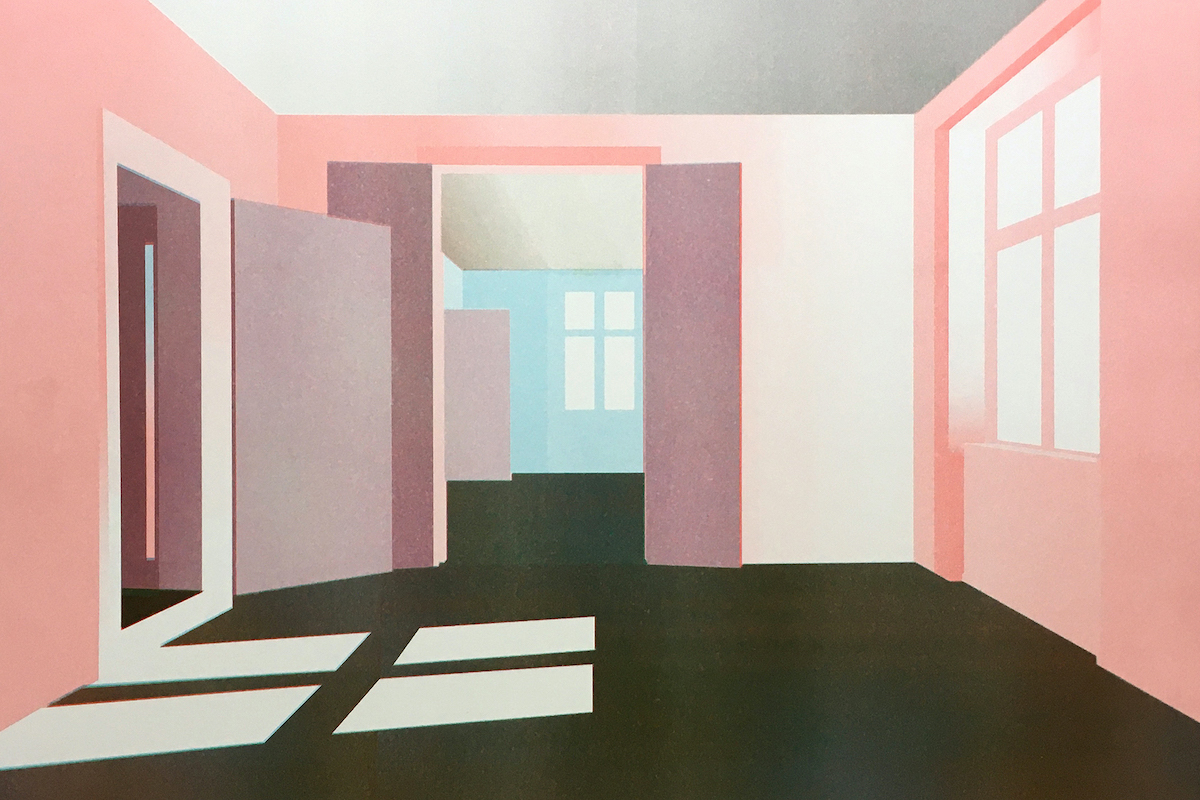

The works exemplify Bergmark’s recurrent use of anthropomorphism as a vehicle for untangling knottier themes, and her eschewal of art-world doublespeak in favour of playfulness and absurdist modes of address. She creates installations that combine sculpture, writing, interior design, sound, film, painting and print pieces. Her current show, Ett Hem (A Home) looks at our modern-day relationship with homes as a community, and ponders Swedish Arts and Crafts painter Carl Larsson’s status as “the first lifestyle blogger in Swedish history.”

- Emilia Bergmark, Potato The Greatest, 2020, video still

Although your current exhibition Ett Hem (At Home) was planned well before the pandemic, it feels like a timely theme. What prompted you to look at domestic spaces?

The exhibition is addressing the question of how the modern home has become a commodity on the market, rather than something that we see as a right. The right to feel safe and have a sense of belonging should be accessible to everyone. My thoughts around the show actually started with observing my sisters’ obsession with websites where homes are for sale. My sisters would browse these websites with images of beautiful houses in the countryside, that are, you know, just sitting there looking for someone to “save them” and make them into a cosy home.

I found it really interesting how this has become a tool for daydreaming. It’s a bit sad, because we would usually think of daydreaming as being about the imagination, but [daydreaming about homes] fits into the contemporary logic of consumption and capitalist realities. I don’t want to diminish that behaviour, and it’s a creative outlet for a lot of people, but people from our generation build their dreams around these images—people who have grown up having to move every six months and will never be able to buy a flat. It triggers something.

“I often use humour as a tool for when I’m trying to say something that is a more harsh critique, and to transcend the subject”

To me that exhibition felt slightly more serious than your previous works, which often use more humorous and absurdist elements within their broader meanings or themes.

I often use humour as a tool for when I’m trying to say something that is a more harsh critique, and to transcend the subject. For example, in my work Burnout I dealt with the biological crisis, looking at how we’re basically at the sixth wave of extinction and this time, man is the reason that all of these species are dying out. It’s a really heavy truth. So I tried to make that truth interesting, or at least digestible, by using anthropomorphism.

The whole show was set up around a conversation between an angry female worker bee who is really upset about her working conditions and a kind of chauvinistic male bumblebee. It’s a subject that’s already so dark and that we’re so sad about (at least I am), so humour becomes a tool to create empathy for something we don’t usually feel empathy with, and to say “come on, let’s continue dealing with this subject, even though it feels hopeless.” It’s also a tactic to open up my work to people who aren’t necessarily acquainted with the art world or literate in “international art language”.

As well as being very funny, there was so much historical and biological background to the Potato the Great project: potatoes’ impact on populations, trade, globalisation; the comparison between the way tubers grow and “rhizomatic” information networks; Marie Antoinette as a potato “influencer”. Tell me more about your interest in potatoes…

If I had to choose one vegetable to eat for the rest of my life, it would be potatoes. Potatoes have been a research subject for some years now, I think the first time I used it as a subject in my art was for a collaborative performance and dinner project in 2011. My collaboration partners in the project, Holly Featherstone and Barnie Page, who run [contemporary art platform] Sacred Thing, wanted me to make an edition. I had been thinking about it for a long time, and then all the pieces just fell into place. I have this archive of pictures from giant vegetable competitions, and I’d wanted to make a talking potato as we have a Mr Potato Head… I like working with symbols that exist in the collective imagination, things that are already there and waiting to be used.

How did you come to be working with the potato that features in Potato The Great specifically?

I asked if Holly could go to the Harrogate Giant Vegetable Competition, and just schmooze with the growers and try and get the winning potato. We spoke together once she was at the show, and I realised that we needed a potato that had a sort of deflated sense of self, the kind of thing you see in Boris Johnson or Trump—they’re constantly having to prove themselves because they have this hole to fill, this megalomania. So it made more sense to use the runner up.

Also, the actual winner was very ugly, from a new variety of potato, which gets much bigger, but from an eating perspective and from an aesthetic perspective it’s quite shit. It’s interesting that when you take something too far, it becomes useless. Well, either way, the runner up was much better, and also it was really beautiful—it had sculptural qualities. And then, to immortalise this specific potato, we found a guy who lives in Suffolk who helped us cast the potato in jesmonite with a pigment to give it the beige colour. It’s really big—about the same size as my face.

“I like working with symbols that exist in the collective imagination”

You’ve used the term “kitchen sink realist” to describe your approach to art. Can you tell me more about what that means in terms of your approach?

It started out as a sort of serious joke. The first time I used it to describe my work was for a show called Heaven and Earth, in which I had three sculptures that referred to food, like a kilo of potatoes sculpted in yellow unfired clay presented on a plinth, and a bronze cucumber. They were props in a more complex story that plays out in a “lifestyle” universe of art and food set in space. But there is a seriousness to the term “kitchen sink realist”.

The term is actually related to the next show I’m working on with Maria Gondek, a Danish artist based in Glasgow. Its subject is the politics and economics of the home, and it’ll be like a radio drama that unfolds in the gallery, but using sculptural objects and sound from voice actors. It borrows a lot of references from the tradition of the kitchen sink drama, but when you think of people like Ken Loach, often the main characters are male. He also has some really good female characters, but usually the focus is on the working man, so I’m going to be talking about the gendered labour of the home.