Steaming nipple factories, ombré sherbet sunsets, hyper-elasticated tongues and saucy broomsticks are key protagonists in Texas-born, Brooklyn-based painter Emily Mae Smith’s strange and glamorous world. Merging neo-pop surface appeal with an uncanny collage of art historical references, sci-fi and classical mythology, her seductive and symbolic tableaux riff on the canon as much as they subvert it.

I spoke to the artist ahead of her collaborative exhibition with studio mate and long-term friend Genesis Belanger at Perrotin New York, where the two have produced a carefully choreographed scene of provocative extravagance for A Strange Relative.

Let’s start with the broom—she’s weirdly human and she’s everywhere in your work.

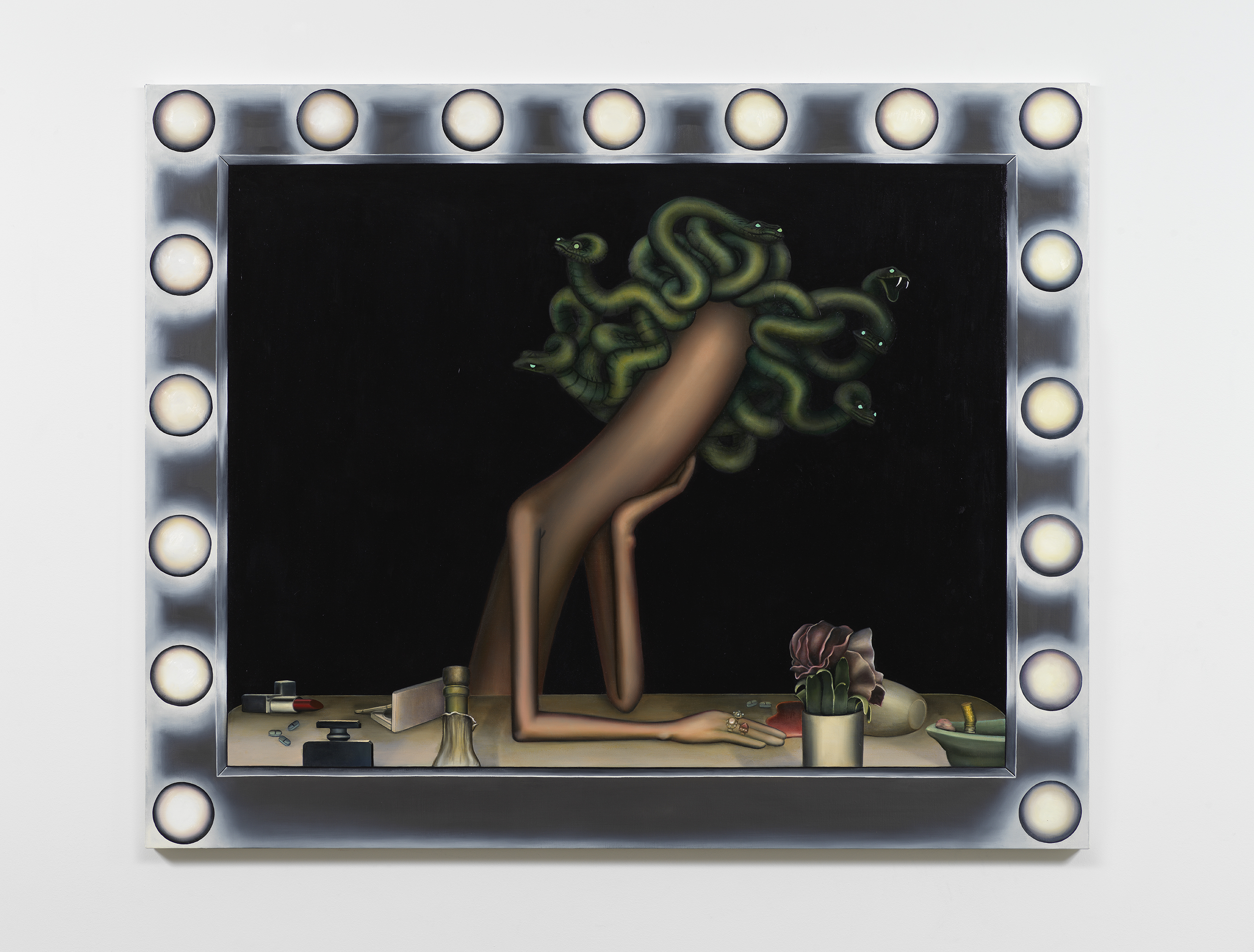

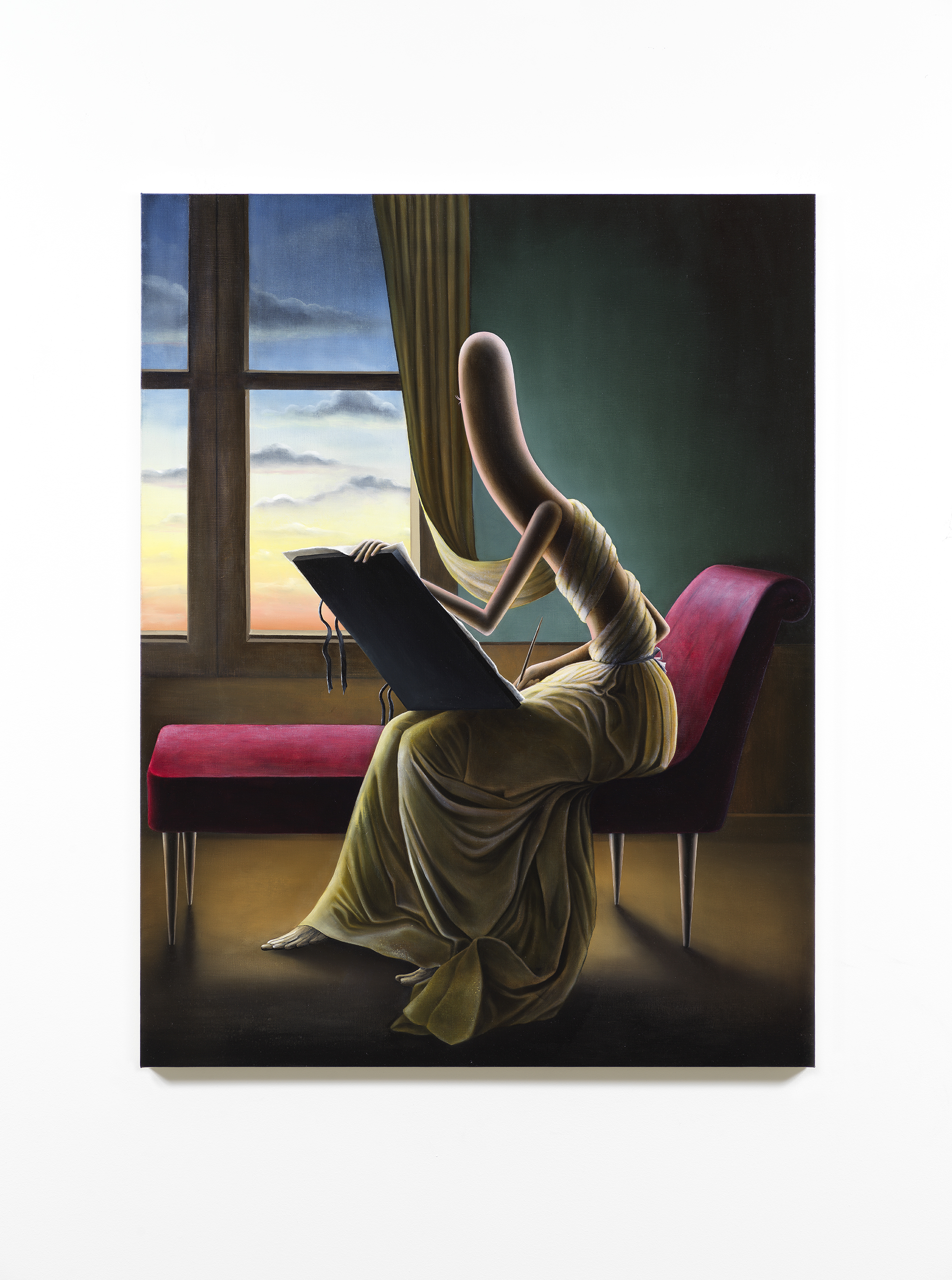

The broom has become this really handy tool for me to work around the gendered connotations that you might get from painting the naked female figure. The broom is nude but you don’t really think about it. And this enables me to place her in all sorts of scenarios—as a glamorous movie star Medusa, as in [my painting] Medusa Moderne, or a contemplative painter gazing out into the sunset, like in The Drawing Room.

Within my collaboration with Genesis the broom takes on additional layers of meaning. She appears next to ceramic hotdogs and cosmetics scattered across the table lining a vanity mirror; she becomes the moody backdrop in an imagined psychoanalyst’s office, within which crossed porcelain finger-studded bouquets rest upon a chaise lounge, which is an amazingly gendered piece of furniture.

In A Strange Relative, the broom embodies the stereotype of the hysterical female, cloaked in domesticity—her legs are literally woven into the curtain, morphing into it—but The Drawing Room is also about the female gaze. It’s based on a historical painting from 1801 by Marie-Denise Villers—which was misattributed to Jacques-Louis David until the mid 1960s, when a female art historian revealed its true creator—and depicts a woman painting a woman, a female portrait of the female artist.

How would you describe your relationship with art history? From fruit, to classical poses, and pop iconography, references abound… but they’re darker somehow.

The history of painting is definitely a big influence for me; having grown up in Texas where there was little access to museums on the scale of MoMA and the Met, moving to New York triggered this kind of fixation.

But instead of going with whatever the canon of art history says, I actually just developed deeply personal relationships with specific paintings, giving them my read. In a sense my paintings are a response to these paintings and the web of social, cultural and emotional weight they carry instead of a reference to them.

There’s this book that I’ve read recently by the art historian Linda Nochlin, author of the landmark 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, that was published in the late nineties. Titled Representing Women, Nochlin here goes through art history and explores these paintings as they relate to interpreting the role of the female and it is totally not at all what art history says these paintings are about. It’s a strong revisionist take that reveals how much of what we think is a given throughout visual culture is actually a highly subjective, constructed language with a singular voice. I want to undo all these dominant narratives that compartmentalize and streamline art history.

The more I see, the more I’m convinced modernism has all its roots in European symbolism, and that symbolism is seen as this very embarrassing grandparent that American artists like to shove out and close the door. It’s funny that in the trajectory of my practice, the further along I get, the further back I wanna go. Last year it was symbolism, now it’s the 1400s…

How do you use humour in your work?

To me, humour in art is like the rope-a-dope: a boxing term coined in the 1970s where one boxer pretends he is more hurt than he really is. When you think he’s totally down and out, at the mercy of the other player, he stands up and lands the punch.

First and foremost, I’m a painter, an artist, an image-maker. I’m trying to make things I haven’t seen or that I want to see. I don’t have all the answers—I’m not an academic; I’m not a preacher. So humour is, for me, a much better way to start a conversation. I don’t have answers, but here’s some ideas!

Humour also allows a huge spectrum of reactions or conversations to happen, which seems crucial in your multi-layered work. I’m curious how growing up in Texas influenced your paintings—I’m sure you encountered certain opinions and belief systems…

It’s funny you say that, because one of the biggest paintings in this show, Fruits of Labor—my first painting of fruit, and my first shaped canvas since art school—was inspired by a particular Texas moment.

In Texas we have vacation bible school in the summer break—it’s basically Sunday school every day. I remember my college roommate went and was asked to draw a representation of God and he drew this giant bowl of fruit that just said G-O-D, and that’s basically this painting.

Texas also influences the colour schemes I use in my work. Growing up in a very rural area, I would have a half-hour drive to school, where I would capture these amazing gradients on an old 35mm camera I kept in my car. They’re fiery hot and golden, like in No Patience for Monuments, but some colour schemes come from New York as well, like in Fruits of Labor, with a cool, silvery northern light that makes the fruits look frozen, or like stained glass. I think about this painting as a sort of reverse sublime landscape, one with an infinite abundance of fruits, which will ultimately all decay.

Can you talk a bit about the element of pop in your paintings?

Around 2013, I started to pare down my work. I was forced to do this by financial instability and constantly needing to move studios. But it pushed my work in the pop direction because I had to cut all the fat—and I realized it made me a much more efficient communicator. Because when you’re so efficient at creating meaning and communicating it, you’re tearing down certain barriers. And certain hierarchies, like the patriarchy, would prefer to keep those barriers in place.

And the other thing drawing me to pop was that it was so uncool. When I first got interested in the style, in the early 2000s, it was seen as ultra low taste, and surface appeal was also deeply not cool. It was better to staple something to the wall and be like, I’m smart, instead of painting something. There was a whole division there that was disturbing, and the antagonism toward pop felt strangely gendered.

For me it’s a really interesting counter-move to pop as perceived as this very machismo movement, with its aggressive graphics and streamlined, mass-production approach.

The first pop-inspired paintings I was making were fontal, laconic, not at all allusions. Like a gun barrel sticking out of a butt and surrounded by teeth, as in The Magician (2014). I was thinking of them as feminist pop, and obviously had a really hard time finding references for that. I was looking to the Imagists but realized these jokes that wouldn’t make sense if they were fussy, they had to be straight to the point—like Joan Rivers, the classic one-liner was exactly what I was going for.

It’s also a condition of being in this time now, who I am and what resources I have. Half the time I’ll finish the painting and then realize—Oh! That’s what I was referencing.

- Installation view of Genesis Belanger & Emily Mae Smith: A Strange Relative. Photo by Dario Lasagni. Courtesy of the artists and Perrotin

A Strange Relative by Emily Mae Smith and Genesis Belanger

Until 22 December at Perrotin New York

VISIT WEBSITE