Emma Talbot’s women don’t go quietly. Loosely sketched on draped silk, or made flesh in three-dimensional installations and sculptures, these women dance and cavort, engage in sexual activity and even give birth to an entire cosmos. There is a mythological undertone to Talbot’s work, as if the personal has been expanded to accommodate past, present and future in a single swoop. Patterned repetitions, yonic forms and the binding line of the umbilical cord keep her women both grounded and suspended in imaginary space.

Talbot has been building her art career for more than twenty years, balancing her work as an artist with bringing up her two sons following the death of her partner in 2006. It has been a long and challenging process, but momentum is building fast around her work following her decision to finally dedicate herself full-time to her practice. Her presentation at Art Night last year, in her local area of Walthamstow, was a highlight of the programme Her brightly-coloured banners were hung in a former cinema and in the William Morris Gallery, and have since been acquired by the gallery collection.

The Max Mara Art Prize for Women comes at the apex of her recent achievements, and offers a unique period of reflection and research. The aim of the prize is to promote and support female artists based in the UK, enabling them to develop their potential with the gift of time and space. Talbot will spend six months in Italy to deepen her skills in everything from the production of ceramics to textiles, as well as exploring the country’s wealth of art historical material. The prize culminates with a major exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery and Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

What led to your interest in tapestry and painting on loose fabric, rather than the more traditional canvas? It has a rich history of everything from protest banners to painted garments. How does this lineage inform your work?

If the beginning of a painting is a rectangular stretcher with canvas, there’s just such a set of givens that dictate what that object, that thing, is going to be. It comes from a modernist tradition; it’s not been that long it’s been that way, but it’s a dominant given in our memory. I realized that I didn’t need it. I’m really interested in Hélène Cixous, who talks about how you can formulate language on your own terms and from a feminist point of view. I then applied that to painting and considered how the surface could be something else: it could be flowing and irregular rather than rigid. You can make these really interesting decisions right at the beginning about what it could be. Silk is very light and fluid, while very strong. It’s a better meeting with my work and my outlook. It’s an idiosyncratic way of doing things, which can be quite direct.

“On silk, if you make a mark then you can’t take it off—just like paper. It’s very immediate, and it stopped me from doubting“

Protest banners come out of wanting to convey a message, wanting to make a demonstration of ideas, which is very different to that traditional root of painting. I really like that the work can be a readable experience. But, to be honest, I didn’t study banners in particular; I just wanted to make something that felt immediate. I wanted to make something that had the same quality as the drawings I do on paper. On silk, if you make a mark then you can’t take it off—just like paper. It’s very immediate, and it stopped me from doubting. It offers a certain freedom; you can just do what you want. For me, it seems liberating. You can trust yourself to make an image or make a text.

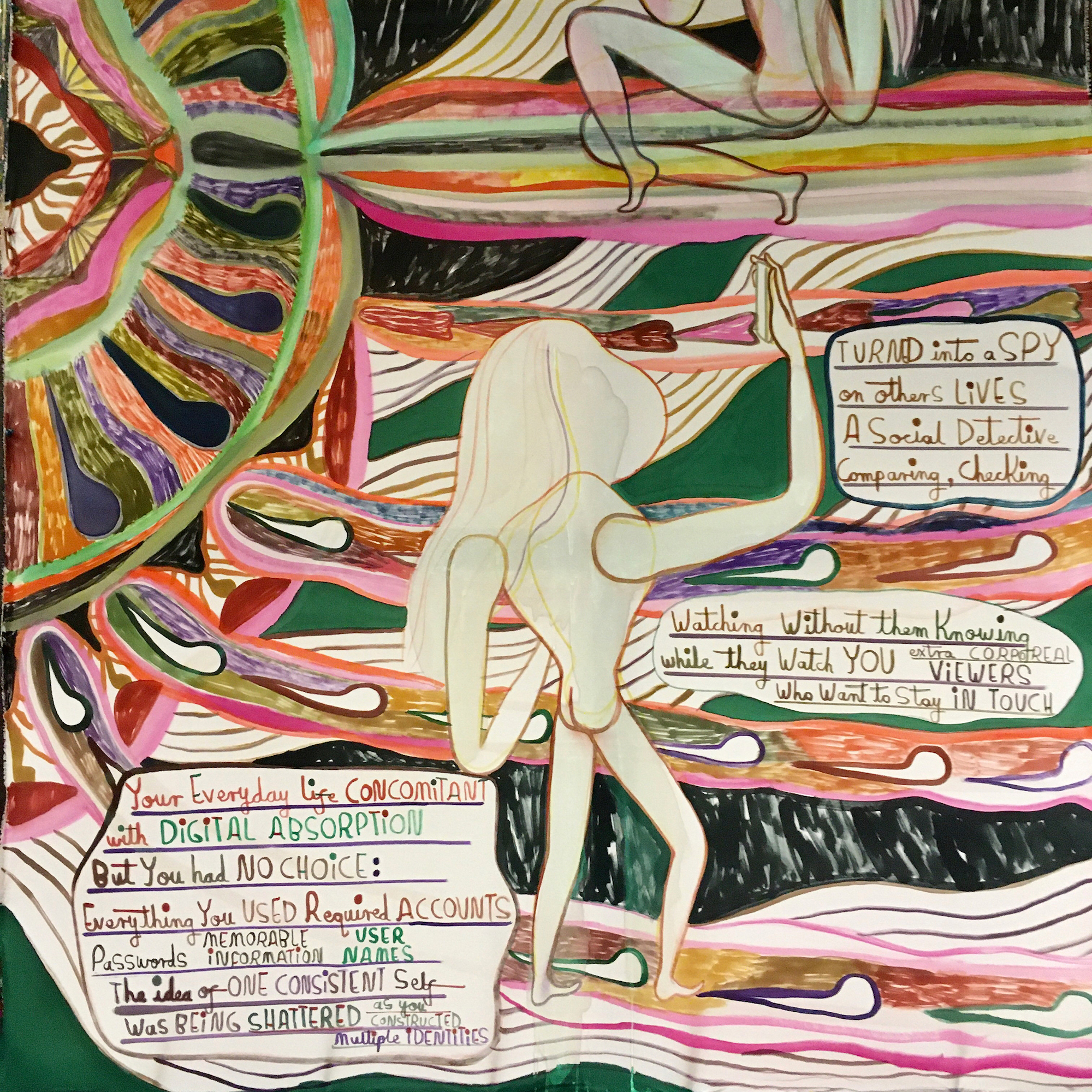

You often create various scenes within a single drawing or painting, akin to a book or comic strip. Why is this, and are comic books important to your work?

I was looking at graphic language when I was a kid, reading comics and so on. I didn’t think of that multi-image way of working directly like comics; rather, it was just a way of having lots of things happening at once. One painting could have lots of images together, and you could gather a meaning or narrative from that. Differently from comics, my drawings aren’t linear. You can focus on details in any order, and you begin to hopefully gather the meaning through a nonlinear looking around. I was trying to convey lots of layered and associative things. I wanted it to reflect how my mind works, and so one image felt reductive. By placing images against patterns, I wanted to create an atmosphere of these ideas.

Your combination of image and text reminds me of the visual style of German-Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon. She created Life? or Theatre? A Musical Play, a remarkable series of paintings on paper between 1941 and 1943, which some have called the first graphic novel.

It’s an incredible work, which I saw for the first time in Amsterdam. The framework is different, set to an opera, and it was one of the things that I wanted to do at the beginning. I was thinking of all these different frameworks for your own life stories. But over time I think that my painting has become about bigger narratives, there are fewer smaller pockets of images, and a personal narrative drops into a more universal space. You see that with Charlotte’s work; it’s personal but overshadowing it are the movements of the time.

We are all within the world, and it’s a really important part of what I’m trying to narrate. We have these very personal private narratives that are always going on in our minds, and we’re also walking around in the world. We have these two things going on simultaneously. In the time of making, you might say that it’s just someone doing something privately for themselves and then it becomes really emblematic of a period of time in the world.

Your proposal for the Max Mara Art Prize explores and challenges the various representations of women throughout visual culture, and particularly in Gustav Klimt’s painting The Three Ages of Women. What were some of your earliest encounters with this subject in art, and how do you plan to approach this work?

This is a painting that I’ve been looking at for a long time. I’ve had an image of it for a really long time, and I’ve been thinking about what it is about it. It’s almost like it’s been poking me to get my attention. Over time my hair went grey, and I was looking at the elderly woman who has her head in her hands like she’s in shame. I thought, why is this elderly woman shameful, and why is it that we think of elderly women as invisible? They become less visible because they no longer fit into a standard of beauty, or they are seen as weak. I wanted to take this figure as a protagonist in my work; I thought of her as a future survivor. It’s all of our future too, as we’re all going to be old, all of us.

I was researching the painting and why it was in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, and discovered that it was bought by them to celebrate the fifty-year anniversary of the unification of Italy. It seemed quite a strange image to choose for the unification of a nation, but then I thought how it reflects a suspicion of old values, and a modernist need for purity and youth; a modernist idea of clearing away the old for a pure future, a scientific space. It’s not just about my own personal response to women and age; it becomes about notions of past and future, and ideals in relation to future and nationalism. Questions of what a nation is and what its values are feature heavily in our current politics.

“Nature used to be thought of in terms of the sublime. I think we have the same relationship to technology today”

I thought that this unlikely female protagonist could explore ways of sustainable living in the future, and also go back to the past to look at power structures and address them. She is undergoing the Trials of Hercules, as I considered how the Classics are often considered the foundational base of our canon. Even Boris Johnson recently used the word Herculean, and it’s a prevalent way of how power is understood. But this woman won’t do the trials like Hercules did them, by violence or colonialism. She would do them by acceptance, and use power in benevolent ways. Power doesn’t have to be aggressive.

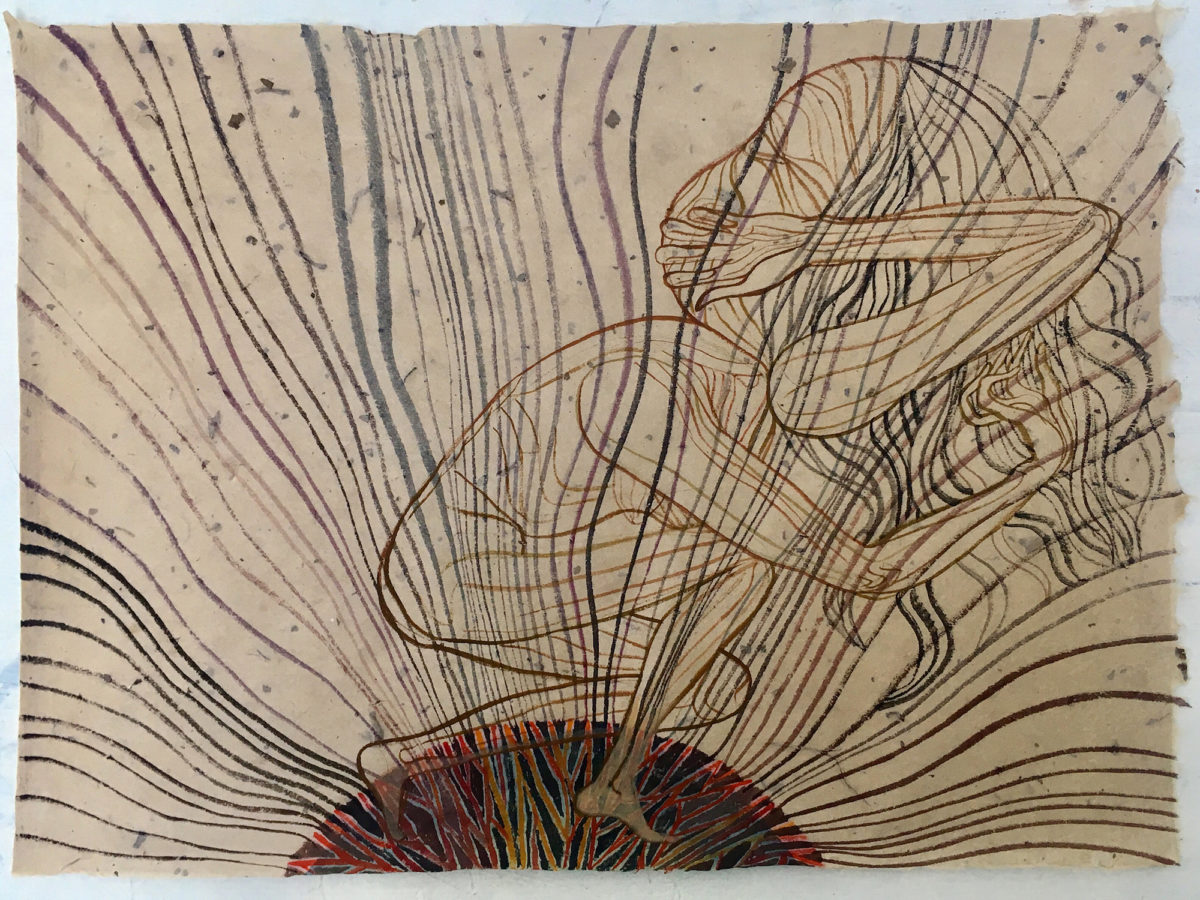

- Emma Talbot, How Is Your Own Death So Inconceivable? Installation view from Sounders of the Depths at GEM Museum Voor Actuele Kunst, The Hague. Photo by Peter Cox

How important is mythology to your work? What would you say are the new mythologies of today?

I would say that technology is our new mythology. I’m making a show for Eastside Projects in Birmingham, called When Screens Break. We know we’re attached to a technological network but we don’t know what it looks like. It’s so big in relation to us that we can’t imagine it visually. This is how people in the past comprehended nature, and they would create ways of understanding it. We don’t have a very universal or all-encompassing understanding of technology, but it has a lot of power over us. Nature used to be thought of in terms of the sublime, where you’d look at it with awe and be slightly frightened of it. I think we have the same relationship to technology quite often.

What has been your experience of ageing, particularly in the context of the art world and working as a woman?

I’ve had a quite particular experience because I became a widow when I was in my mid-thirties. I had two sons, who were six and seven at the time, and I had to support us. I was teaching in art schools to support us to live, and just juggling all of that, working in the studio, going to work and raising a family. My work has evolved fairly slowly in terms of it coming to a wider audience and I am a bit older than most emerging artists. But it’s something that I’m proud of, and I’m proud of raising two children in London, where it’s hugely expensive to live.

I had a particular set of challenges and I feel that, as my work develops, I can meet them with the new opportunities I have been offered. I feel like recently my work has had a lot of support, but it’s taken a long period of time. It was hard, but luckily my sons were brilliant and they never made any question of what I wanted to do as an artist. It’s been amazing to receive this prize; it has come at the right time for me.