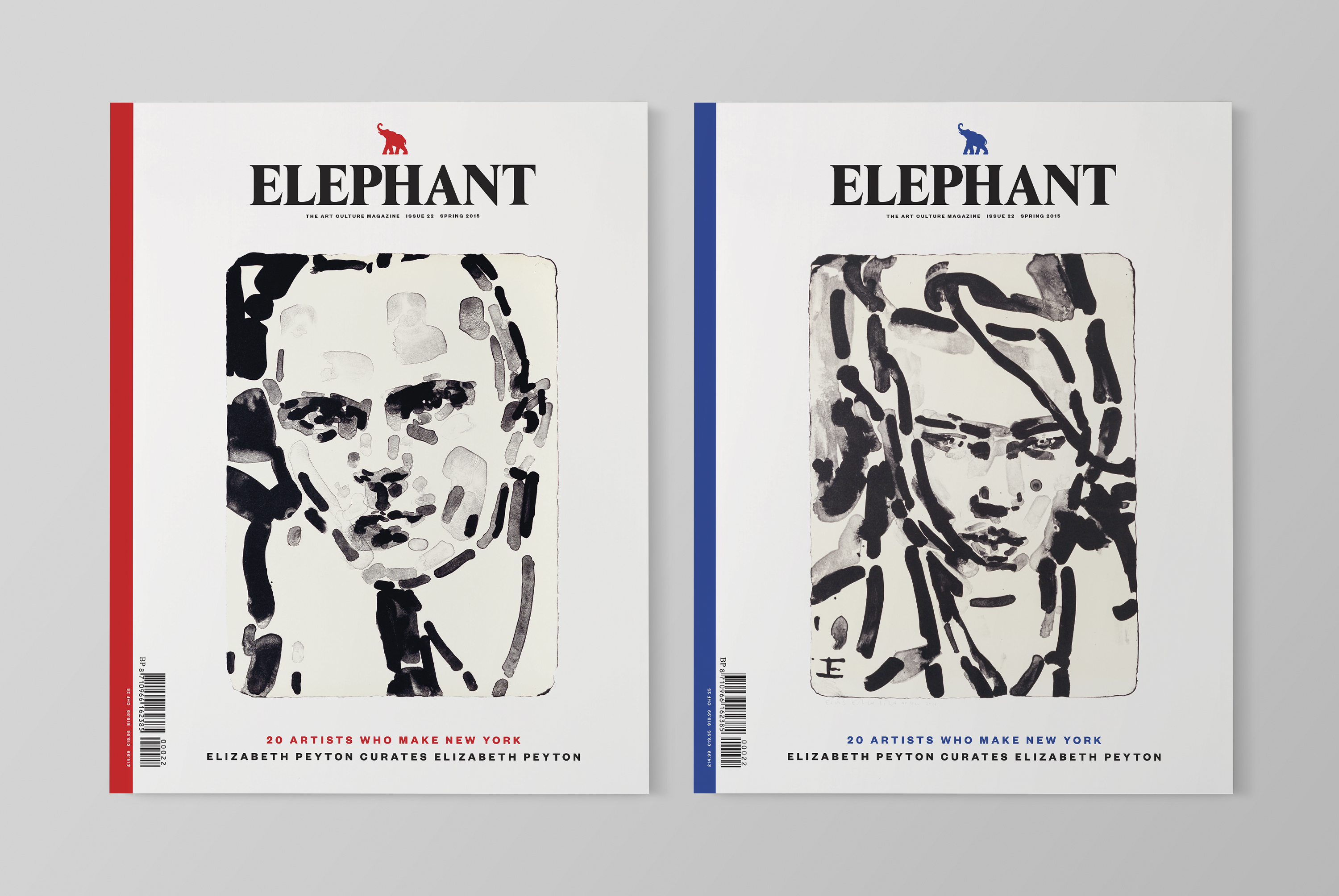

After drawing record-breaking crowds in Brussels and Tel Aviv, Michaël Borremans’ travelling survey show, As Sweet As It Gets, arrives at the Dallas Museum of Art. Katya Tylevich talks to the show’s curator, Jeffrey Grove, to trace the development of the artist’s style and to discover why it connects with so many people.

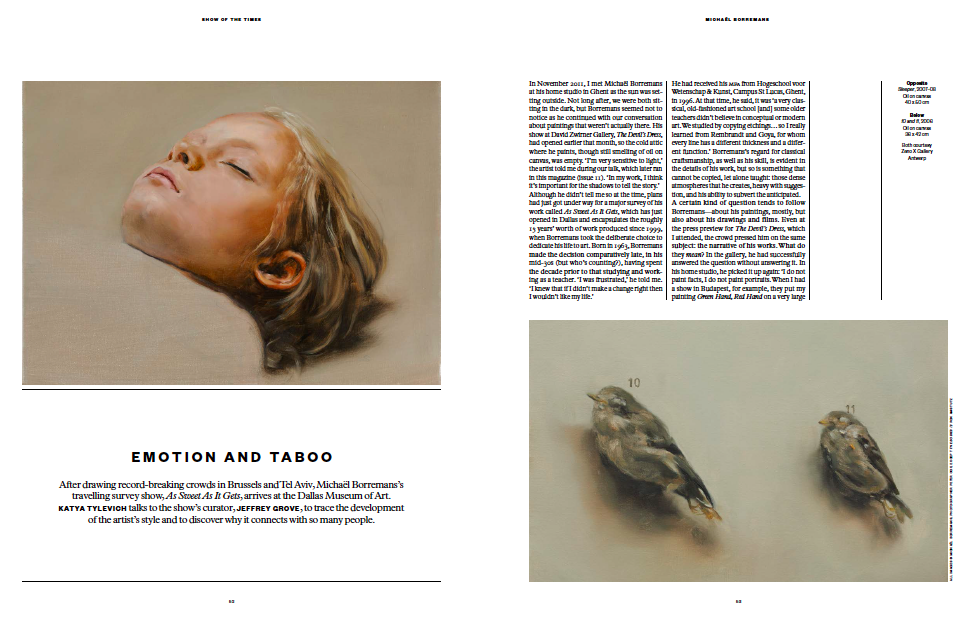

In November 2011, I met Michaël Borremans at his home studio in Ghent as the sun was setting outside. Not long after, we were both sitting in the dark, but Borremans seemed not to notice as he continued on with our conversation about paintings that weren’t actually there. His show at David Zwirner Gallery, The Devil’s Dress, had opened earlier that month, so the cold attic where he paints, though still smelling of oil on canvas, was empty. ‘I’m very sensitive to light,’ the artist told me during our talk, which later ran in this magazine (issue 11). ‘In my work, I think it’s important for the shadows to tell the story.’

Although he didn’t tell me so at the time, plans had just got under way for a major survey of his work called As Sweet As It Gets, which has just opened in Dallas and encapsulates the roughly 15 years’ worth of work produced since 1999, when Borremans took the deliberate choice to dedicate his life to art. Born in 1963, Borremans made the decision comparatively late, in his mid-30s (but who’s counting?), having spent the decade prior to that studying and working as a teacher. ‘I was frustrated,’ he told me. ‘I knew that if I didn’t make a change right then I wouldn’t like my life.’

He had received his MFA from Hogeschool voor Wetenschap & Kunst, Campus St Lucas, Ghent in 1996. At that time, he said, it was ‘a very classical, old-fashioned art school [and] some older teachers didn’t believe in conceptual or modern art. We studied by copying etchings… so I really learned from Rembrandt and Goya, for whom every line has a different thickness and a different function.’ Borremans’s regard for classical craftsmanship, as well as his skill, is evident in the details of his work, but so is something that cannot be copied, let alone taught: those dense atmospheres that he creates, heavy with suggestion, and his ability to subvert the anticipated.

A certain kind of question tends to follow Borremans—about his paintings, mostly, but also about his drawings and films. Even at the press preview for The Devil’s Dress, which I attended, the crowd pressed him on the same subject: the narrative of his works. What do they mean? In the gallery, he had successfully answered the question without answering it. In his home studio, he picked it up again: ‘I do not paint facts, I do not paint portraits. When I had a show in Budapest, for example, they put my painting Green Hand, Red Hand on a very large banner, and the curator told me: “I want people to see it, because it’s a political work.” He had to explain to me

why that is. He said: “This painting explains the situation in the country we live in. It shows two contrasting hands, but they come from the same body. That’s our problem.” I like that. It means I made a good work, when someone can use it for a purpose I didn’t intend. But I also subscribe to the Romantic idea that art is always an expression of yourself. In some way, the works are all biographical. That’s almost taboo to say, which I find strange. Art is emotional. It should be.’

The emotional aspects of art—the shadows—may be difficult or even unnecessary to articulate, but they are what make a work irresistible. Often, those shadows are the foremost draw for an audience, especially one extending beyond people primed to look at art within academic brackets. Borremans’s work certainly lends itself to academic reading, but perhaps more important is that it is equally available to anyone entering the museum with no expectations or previous knowledge of the artist. That quality, however indefinable, helps to explain the record-breaking attendance rates for As Sweet As It Gets, which puts on display close to 100 of the artist’s paintings, drawings and films.

The show’s curator, Jeffrey Grove, an independent curator living in New York, and formerly senior curator of special projects and research at the Dallas Museum of Art, has followed Borremans’s work since the early 2000s and has developed a close working and personal friendship with the artist. A month before the Dallas opening, Grove tells me that ‘when people talk about Michaël’s work, they talk about beauty, humour and darkness in the same breath. They are referring to the emotional qualities of the work… which doesn’t happen when someone walks into an exhibition of abstraction or conceptual art.’ One of Grove’s intentions with the survey, he says, is to give people something to talk when they draw their next breath: the ‘intellectual qualities’ of Borremans’s work.

Grove says that the importance of an artist and a signifier that the artist’s work will resonate across different continents is not only measured by the subjective feelings that the work might arouse, but by the more impartial qualities of influence, relevance and circumstance. In our conversation, Grove explains the enormous process and pay-off of an exhibition of this scale:

How did you decide on the selection of works in the show?

Michaël and I worked closely on the show from the beginning. We probably went back and forth for six to nine months over the selection of works, which is a difficult process whether an artist has painted 200 pictures or 2,000 pictures. We would get together and look at images. Because I have a long history with Michaël, I’d seen many if not all of the works in person over the years, so we were able to talk about them in more depth than if we were just working from reproductions. Certainly we negotiated, but I think we’re both pleased with the final outcome.

We shared a vision in that we wanted to represent the breadth of his career and strike a balance between his painting, drawing and film. A lot of people are familiar with his paintings, but don’t know his film, and the drawings might also be somewhat of a surprise. While [the drawings] are completely concerned with a lot of the same issues as his paintings, they have a different quality and narrative content.

The exhibition encompasses about a 15-year arc, starting from when he began to dedicate himself to drawing and then, a little bit later, to painting. Although we didn’t want to privilege certain periods over others, we necessarily wanted to show the development technically in his work over time. There are a few more paintings from certain periods where you can really detect increasing sophistication in the handling of the paint or the technique—2005, 2007–08 and a body of work that was produced in 2013.

In his earliest paintings, Michaël used found source material—images that he took out of books or magazines or off the internet. Then at a certain point he realized that those images are sort of tainted by nostalgia or history and that people were bringing associations to them. So he began to construct his own images in the studio and photograph them, then create from there. He took on a more auteurial voice, you could say, and you can detect the change. It’s also reflected in the technique, the way he’s handling the paint: Michaël is always studying technical aspects of painting, and as he paints more, he becomes more sophisticated in how he mixes glazes and oils and applies the paint. You see the paintings taking on a deeper aura.

Have any responses to the show surprised you?

At

BOZAR in Brussels the show was the best attended they’ve ever had. I couldn’t believe how many people were there just at the preview on opening night. Then we turned around and went to Tel Aviv and it was the same thing. We just don’t have openings of that size in Dallas or Cleveland or Atlanta, or any of the institutions I’ve worked at. You don’t really see that in American institutions at that scale. I think it says something about the way culture is consumed in different parts of the world, but also about the interest in his work. The rabid level of interest in his work is exciting.

What indicates to you that it’s time for a survey of an artist’s work?

I’m always interested in artists whom other artists are looking to and talking about—artists whose effect you see on younger generations. There was so much attention among artists and art students and serious collectors with regard to Michaël’s work that it needed to be exposed to a larger audience. A survey is a measure of an artist’s influence, and a way to put it into context—in this case, with currents in portraiture and the revival of the figure and figurative painting, even though Michaël would argue that he doesn’t paint the figure. This survey is about the idea of tradition in painting and a question about what tradition is. These are issues that are implicated in Michaël’s work, and are relevant particularly at this time.

This feature appears in the current Issue 22