A series of paintings by Nicolas Ruston declaring ‘The End’ proved just the beginning for a series of writers. Text: Sue Hubbard

‘In my end is my beginning,’ wrote T.S. Eliot in Four Quartets, somewhere between 1935 and 1942, in the midst of the Second World War. The work was that of a mature poet facing a world riven by war and increasingly neglectful of its past, a poet in search of a spiritual narrative. But in another decade and another century, art and literature find themselves inhabiting a very different terrain. We look round to find ourselves without a coherent narrative. Centres, as Yeats predicted, do not hold. Not only are they lacking in conviction but they are void of definition and clarity. We discover not only a refusal of the sacred in favour of narcissism but a loss of belief in any system of values beyond the self. Meaning is negotiable. One beginning or end is as good as another – and what, anyway, in a culture of endless circularity and avatars do such terms mean when everything is interchangeable? Technological progress has usurped its own utopian ends to lead us back, not to Eliot’s Ouroboros-like beginning, but to a place of dissolution and alienation.

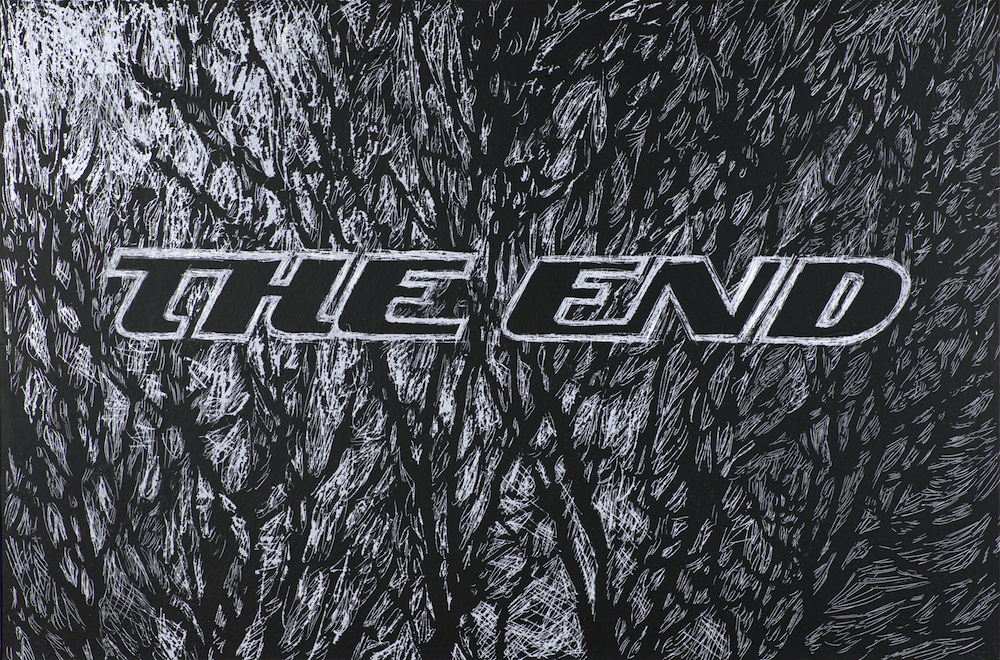

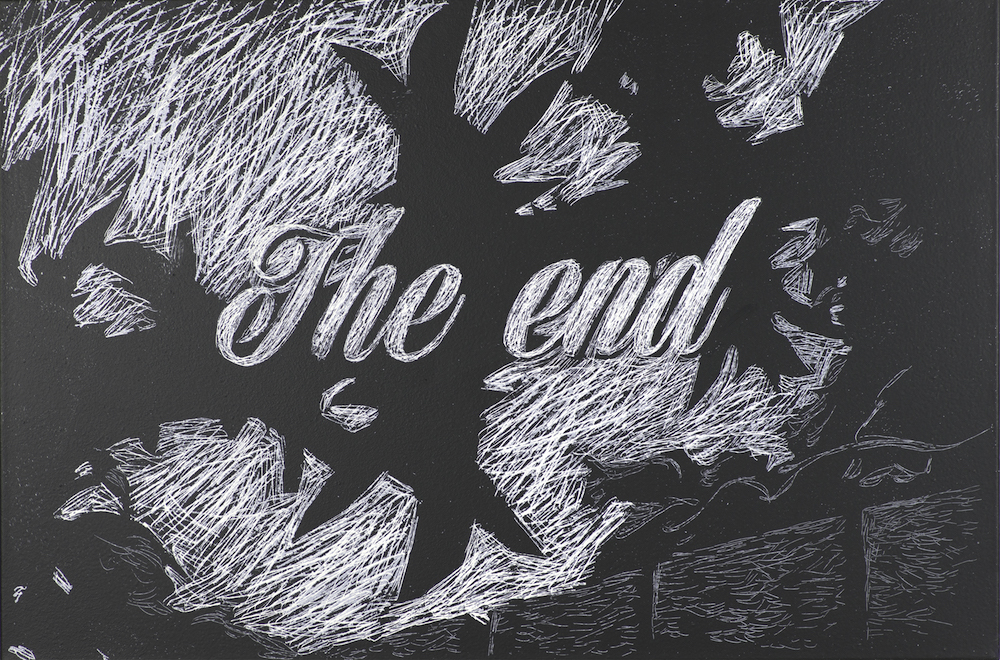

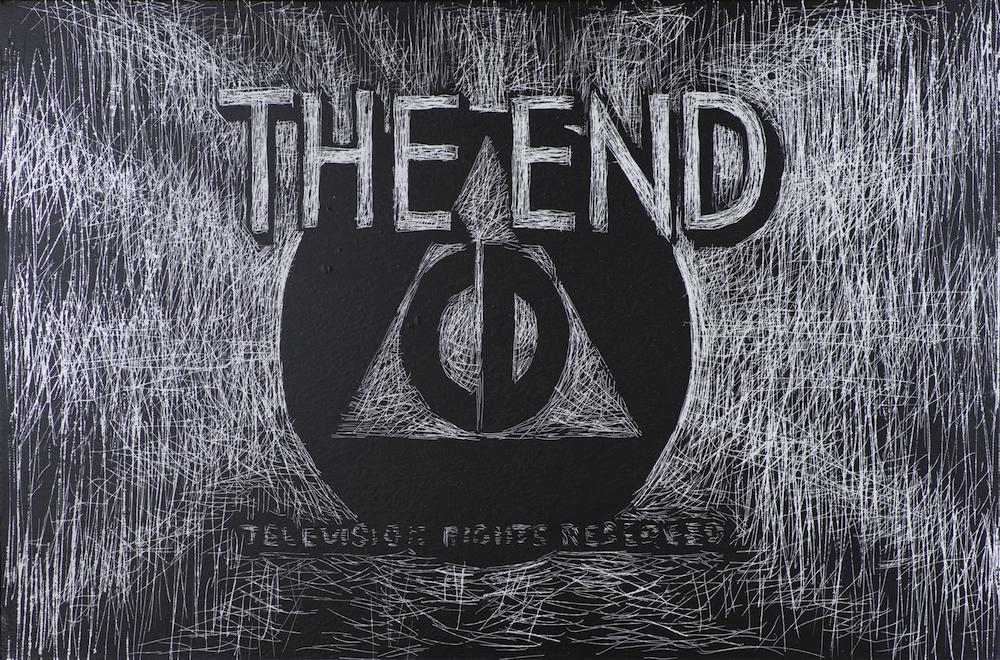

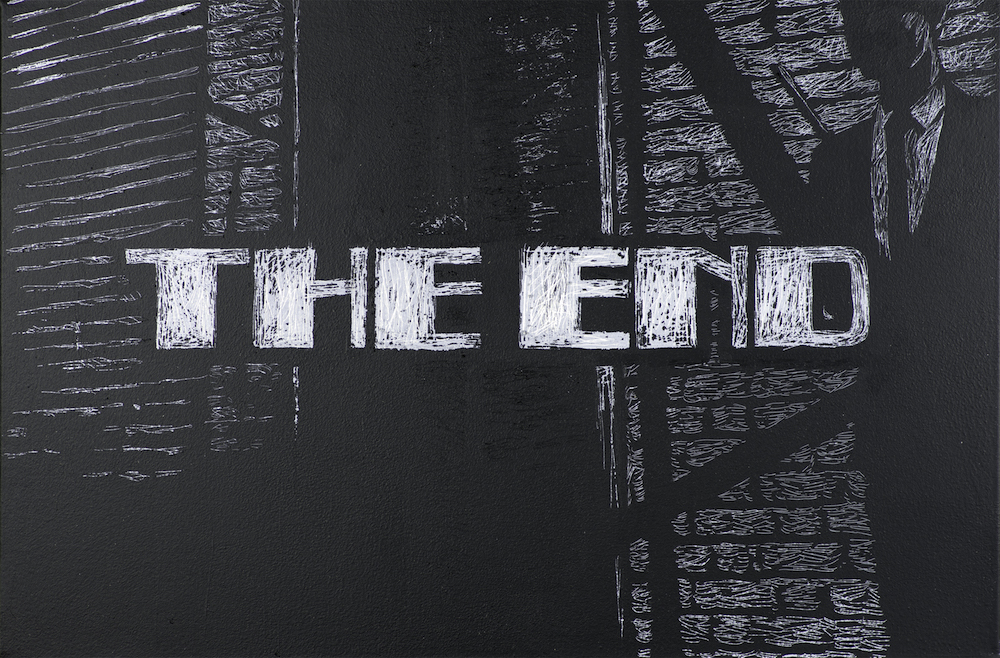

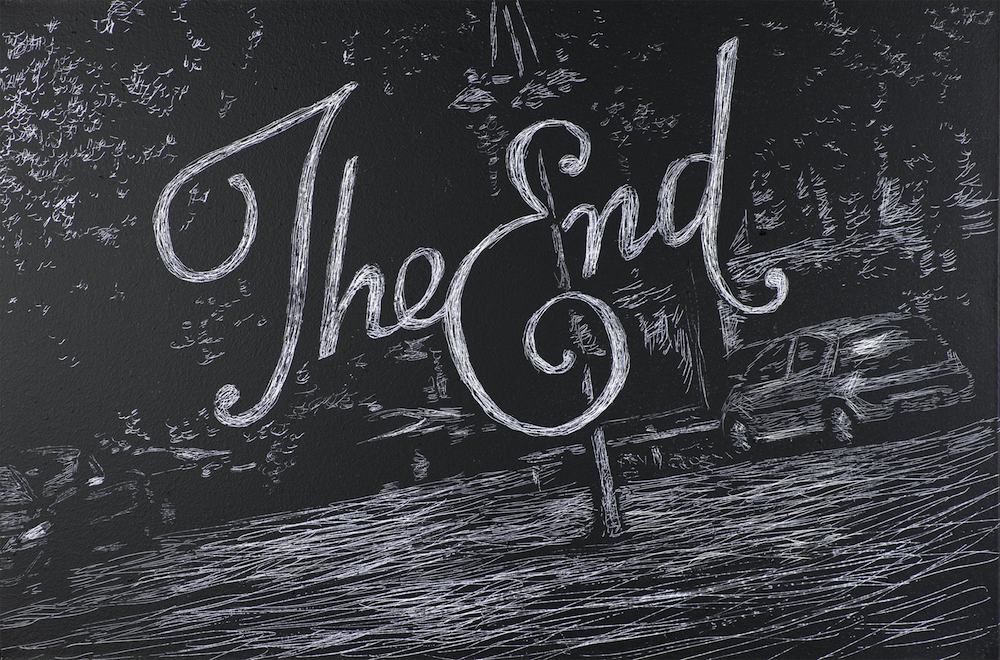

For his project The End, Nicolas Ruston has produced a series of 15 paintings. The different typographies suggest the end titles from period movies, the sort of films made in the early 20th century when ‘The End’ appeared on the screen against swelling music, to assure the viewer that not only had moral certainty been restored but that the film’s protagonists would live, if not happily ever after then, at least, restored to their proper place in the order of things.

With a background in advertising and marketing, Ruston has long been fascinated by how mass media images bleed into our constructions of reality. The varying topographies he employs in these ironically nostalgic, black and white paintings imply narratives that are never stated. The imagery is generic – a wet city street, where a low-slung black saloon is parked by a sidewalk that might, at any minute, disgorge a couple of undercover cops in trench coats and fedoras; or a little house on the prairie where we can imagine grandpa leaning on the farm gate to share a few homespun homilies. These are just two of the scenarios that suggest multiple storylines.

Ruston handed over his paintings to 15 writers to interpret their backstories as they chose (and now published by Unthank Books). Implicit in this conceptual gesture is the notion that the, apparent, finality of the texts produced is anything other than illusory. A myriad of other stories might have been written in their stead. Truth, we learn, is no more than a series of shifting images in a hall of mirrors.

Ruston’s scratch-painting technique has been developed through trial and error using household gloss and masonry paint. Influenced by the scalpel pictures of the artist Edith Simon, whom he met in his teens, his years of producing models for pop videos have also left their mark.

‘”Truth”,’ Victor Burgin writes, ‘was a principal character in the allegorical canvases of humanism; in post-modernist allegories Truth has been replaced by the twins “Relativity” and “Legitimation”.’ Ruston’s project illustrates that in our fractured world, what we view as The End is a matter of preference and interpretation rather than fact.

‘The End: Fifteen Endings to Fifteen Paintings’ by Nicolas Ruston runs at The Library, 112 St Martin’s Lane, London WC2N 4BD until 24 November.

The End ‘Harbour Lights’ (2015), Nicolas Ruston, Gloss and masonry paint on canvas, 51 x 66cm