British multi-instrumentalist and performer Gazelle Twin (aka Elizabeth Bernholz) emerges like some shape-shifting apparition, stalking through a variety of weirdly familiar landscapes, from the intoxicating, otherworldly panorama of her debut album The Entire City (2011), through the urban pressure of Unflesh (2014), and most recently, the vividly warped images of Merrie Englande on Pastoral (2018). This multi-layered vision is the fruit borne of what she describes as “getting locked into a mood and running with it”.

Several years ago, Bernholz and her musician partner Jez relocated from their Brighton base to the midst of the Leicestershire countryside; the move away from city life and closer to a different kind of nature seemed to yield new stirrings and undercurrents in her work as Gazelle Twin. It also tapped into personal roots, as the move brought her back to a former family home, where she had studied music as a teen, and developed a fascination with early music and choral compositions.

“It was a slow, painful process, but everything came out very clearly”

“I hated commuting to London, but I got a lot out of it,” she murmurs. “I was spending a lot of time being uncomfortable, underground… I think that a lot of that feeling definitely got channelled into Unflesh… With Pastoral, it was about having an almost rural folk quality, and mixing that with anxiety— the result of what was going on in the world, and my own life.”

While Pastoral propels Gazelle Twin into outside realms, it is in its own way, intriguingly claustrophobic—not least on the harsh rasp of its lead single, Hobby Horse (“My hands are tied, and I can’t get out of here”). The album came together in “twenty-minute bursts, between breastfeeding and sleeping”, as she adjusted to new motherhood, and observed the increasingly tense environments around her. “It was a slow, painful process, but everything came out very clearly,” she recalls.

Pastoral also ran with the dystopian themes explored in Gazelle Twin’s previous work, Kingdom Come (originally commissioned by Manchester’s Future Everything festival in 2016). This audio-visual project, created with ace indie filmmakers and regular collaborators Chris Turner and Tash Tung, was based on JG Ballard’s final dystopian novel, which depicts a middle-class commuter-belt community turned feral and fascistic through rampant consumerism. Although Bernholz herself didn’t appear onstage during that show (its chillingly faceless characters were played by Natalie Sharp, aka The Lone Taxidermist, and Stuart Warwick), she was distinctly present, through its mesmerizingly murky soundtrack, and the use of costume as a means “to transcend flesh”.

Bernholz mentions that Pastoral’s visual themes came coincidentally, early on in the work’s inception (and with the backdrop of 2016’s EU referendum, which would spiral into the seemingly interminable limbo state of “Brexit Britain”). “I found an ‘England’ cap, plain white with a St George’s cross, in a charity shop,” she says. “The cap is obviously quite an iconic piece of contemporary streetwear, but there’s also something about this particular symbolism that’s really frightening—I wanted to dig a bit deeper, and find out why. I took a couple of pictures of myself wearing it, with a grimace…”

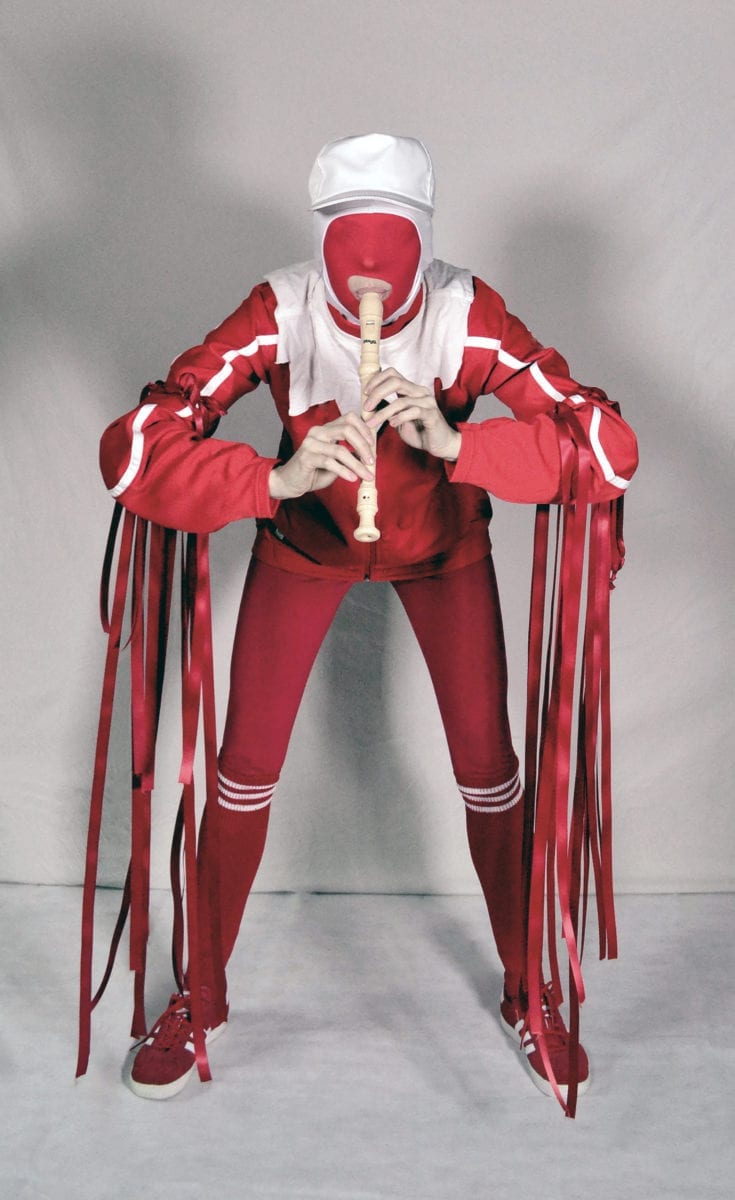

Bernholz’s pearly-white grimace—or demonic grin—is the only part of her face visible in her Gazelle Twin guise for Pastoral: this time, she appears as a red-and-white devil-cum-court jester in sports casual, looming at the edges of a bucolic scene, or raving and rampaging through the woods in the Hobby Horse

video.

“I’m always banging on about pagan costumes and dance rituals!” laughs Bernholz. “I’m fascinated by their layers of meaning, and the way that they use everything that’s around as material: leaves, straw… I felt like the jester was the ideal symbol for all of the meeting points on Pastoral, and there’s also an element of Commedia dell’arte masked theatre, which I love.

“I don’t know if the music on Pastoral is ‘earthy’ so much as very basic,” she says. “I used the cheapest recorders. I didn’t want to sound ‘organic’, as I feel like that’s such an over-used word, but I did want to feel that we were in the earth, that there was a deep landscape there: the jaunty folk stuff, the creepy woodland stuff, the almost suburban woodlands…”

““I’m always banging on about pagan costumes and dance rituals! I’m fascinated by their layers of meaning”

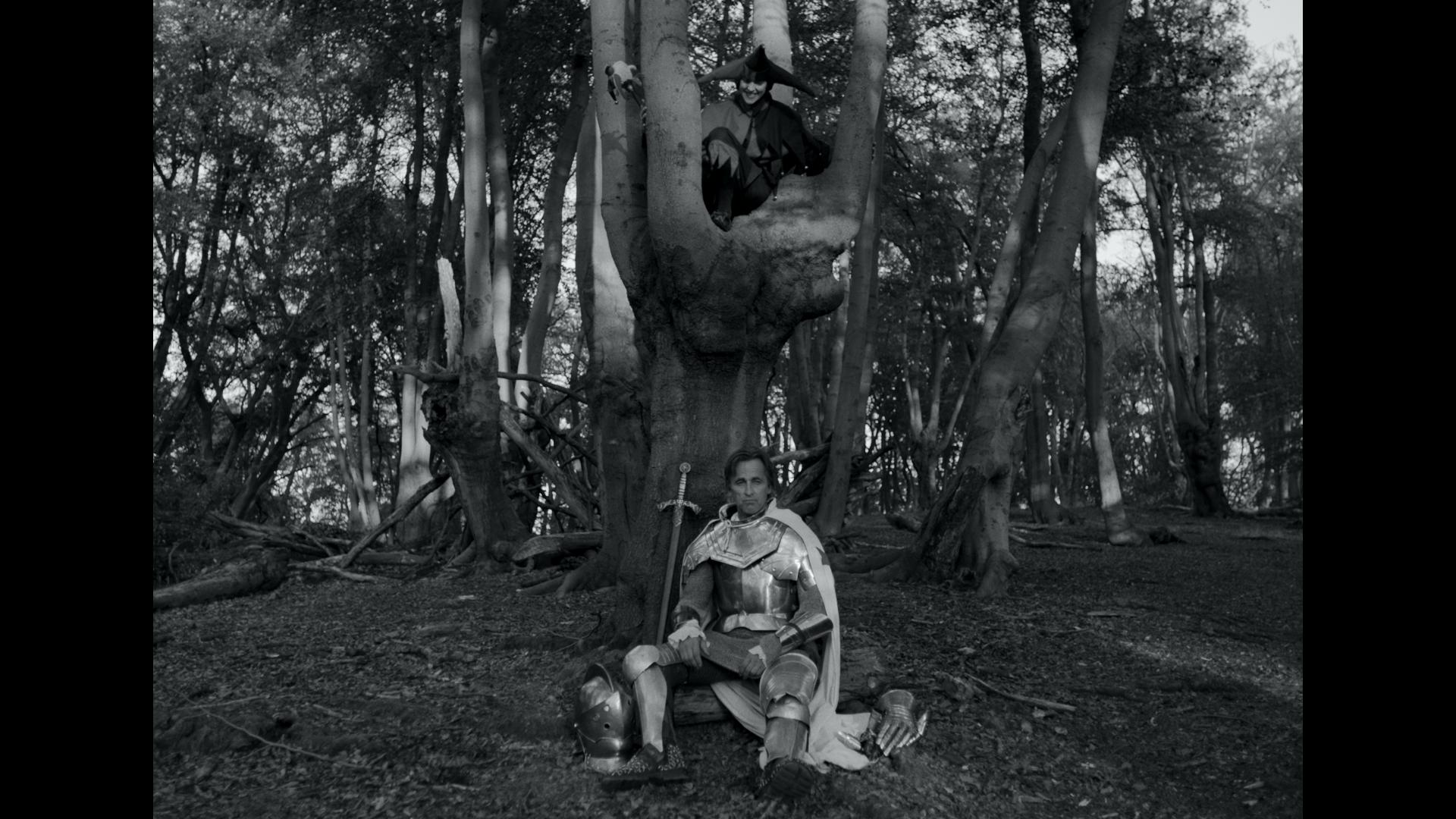

That landscape was fleshed out further in the video for another Pastoral highlight, Glory: shot in the atmospheric depths of Epping Forest, with actor Crispian Belfrage playing a brooding knight, and Bernholz appearing in different forms: the jester; a nun; a fleeing maiden (a call-out was also made for members of the public to play plague-ridden dancers; I very nearly signed up).

Bernholz found herself thinking about how heritage and patriotism is constantly repackaged, from the Crusades (“How did such a brutal regime end up becoming these knights of valour?”) to the stocks on show in the local village: medieval instruments of torture transformed into quaint curios for daytrippers. “We filmed the video over a hot weekend, and got bitten to death by fleas,” says Bernholz “But it was amazing, wandering through this beautiful forest, finding all of these strange corners.”

Gazelle Twin’s forest forays continue with her next live date, as she performs Pastoral as part of Waltham Forest’s Borough of Culture programme in September. This may be the final outing for Pastoral’s jester persona (Bernholz treats each album as a distinct live phase), but Gazelle Twin continues to transform to captivating effect; in November, she will perform a special London Jazz Festival show, in collaboration with experimental choir NYX, who combine electronics and vocal techniques.

“NYX are this really wonderful group of people, who adore drone music,” says Bernholz. “The collaboration really tunes into some of the themes that the music brings out, including witchcraft. We wear these red veils, which resemble something from [Dario Argento’s] Suspiria. It’s almost religious, very intense, beautiful and symmetrical.” The past and the near-future are intermingled in Bernholz’s vision, and they spawn febrile, fantastical offshoots.