“Where would you like to start,” says Eric Fischl as we walk around his solo exhibition at Skarstedt gallery in London. Where would he like to start, I insist. “Well I was born in a log cabin,” he says, joking. This opening story is a typically American one. His paintings are stories—narratives of a fluctuating but mostly terminal American Dream that are often compared to the work of mid-century American novelists: bards of suburbia, such as John Updike, John Cheever and Richard Yates. He has lived for much of his life on Long Island, where F Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby lived; many of his most recognizable images take place around a pool, which for Fischl functions as a hearth of listless American privilege. His paintings have a heavily allusive literary feel, even if they aren’t allusive to a concrete thing. Does he read a lot?

“I knew the upper-middle class, the dysfunctional alcoholic family; I knew that space between what things look like and what they feel like”

“I wish I did,” he says. “I’m slightly dyslexic and have an attention deficit thing, so I find it laborious to read. But I see myself as coming from the oral tradition.” In the eighties Fischl was lauded by Warhol and grouped alongside the still-living Basquiat. His breakthrough works such as Bad Boy, Sleeper and Daddy’s Girl allude to suburban repressed desires and oedipal ambiguity. “Literature had begun to do that before, and in film they were doing that as well. But when I came up into narrative figurative painting, there was no genre for that. It didn’t recognize the suburbs as a place of content. You had the bucolic pastoral; the high life of the city or the low life of the city. There was no sense of the suburbs. But my generation was the first to grow up in the suburbs. We knew there was lots of content there. And the critique against painting then was also so intense—as well as the critique against certain kinds of painting—that I needed to find something that I knew was authentic that they couldn’t take away from me. So where do you go? You go to what you know. I knew the upper-middle class, the dysfunctional alcoholic family; I knew that space between what things look like and what they feel like. It provided a life’s work.”

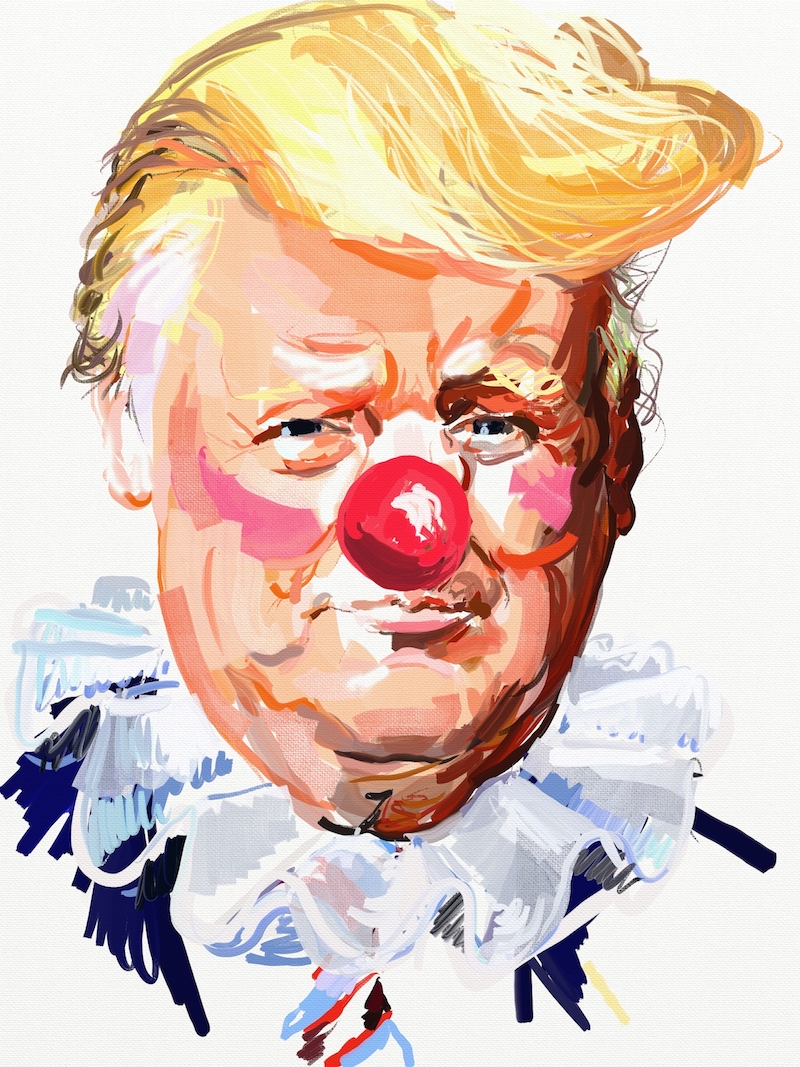

In Fischl’s childhood there was the money and the appearance of prosperity that comes with it. His mother was an alcoholic who dabbled in various art forms. She took her own life while Fischl was in California on an art school scholarship. He became a master of painting the surface of this kind of gilded life, while also suggesting an underside that isn’t always concealed. Now the gilded philistinism is seen in his interpretations of the White House. “I see it as a desperate moment. People are holding onto the most absurd stuff as a reaction to the utopian world that was promised in the fifties. The events of 9/11 terrified us in a way we never fully acknowledged. We just started to run, and ran into smaller and smaller protected groups. As well as all those people who were killed, our self-image was destroyed. Everything let us down, including our sense of self. We ended up with Trump, the most ludicrous example of the white male image.”

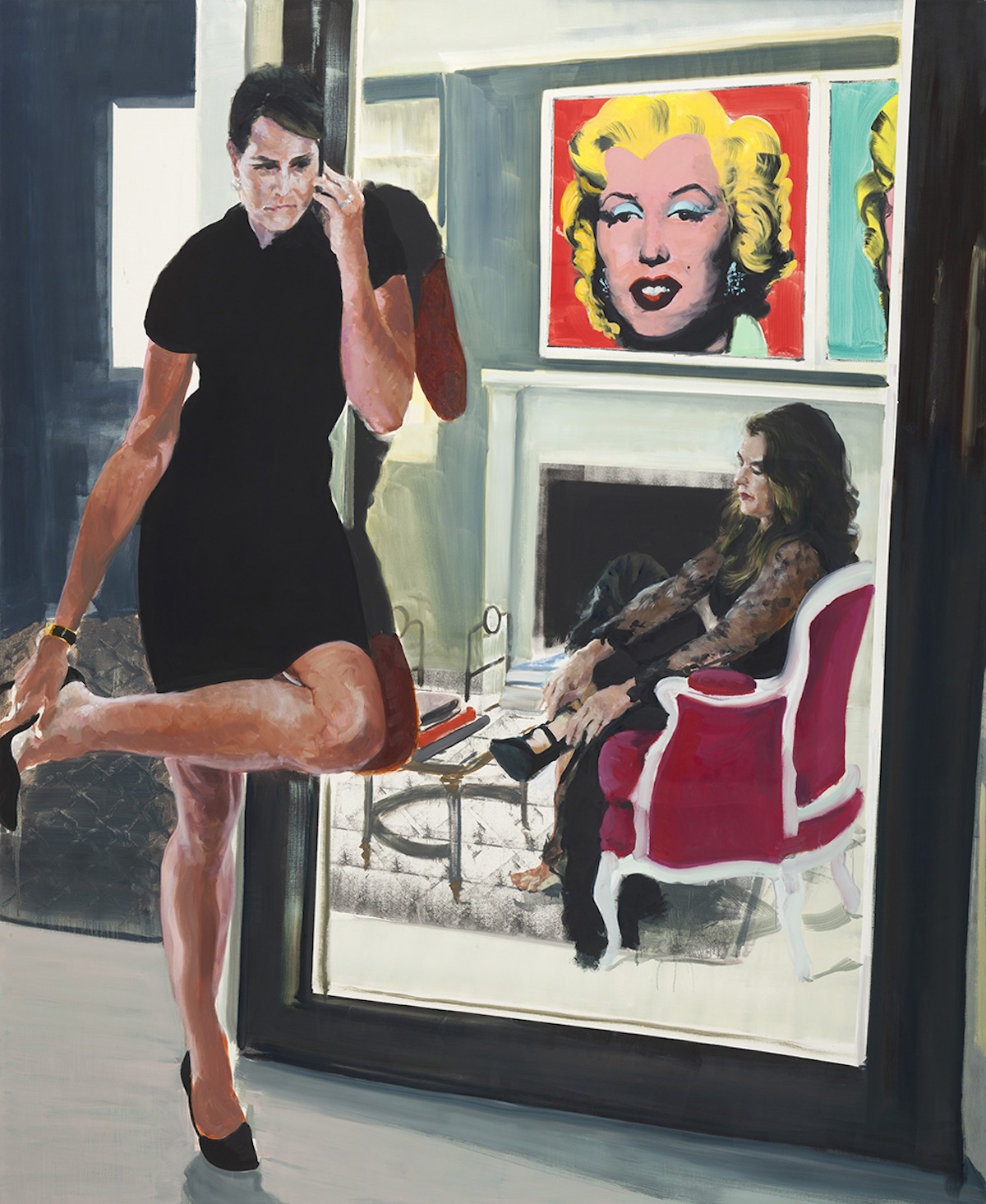

Days after the election Fischl posted his painting Late America on Facebook. The painting shows an inconsolable naked man lying by a swimming pool, as a kid draped in a flag just looks at him. He has also painted cartoons of Trump’s cabinet—he started for amusement, then this turned to escapism—on the ArtRage iPad app. His most striking image, of Trump with fully coiffed hair and clown nose, appears in the background of his latest paintings. These scenes begin in Photoshop, with Fischl taking photographs of individual parts of what will become a collage from which he then paints. “With a model they want to pose. But I can’t tell a model what I am looking for because I don’t know. I have to see it. You work with an actor and you give them some problem, man they can take it into an incredible space.”

He talks about one of the “wonderful” actors he worked with on an untitled work, in which one woman offers a tissue to another. One is veiled by lace, another by a cloud of smoke. Who is she? “Brooke Shields”, he says in a no-big-deal kind of way. “It’s not a portrait of Brooke: it’s a character that she created. I was thinking, ‘You’re sisters, you’re identical twins.’ I said ‘Okay. You’re two different sisters that are dealing with the same loss. What is it?’”

“For me the one higher purpose is to try to keep the empathy channel open”

This “What is it?”—a quality of subtle inscrutability—is everywhere in the new works. In The Appearance, a couple get ready in a twin room. A man who looks like a Baldwin brother is in a black bathrobe and the woman is in mourning dress with a whiskey in her hand. But if this is a time of mourning, why have they travelled with the incongruous butterfly suitcase which sits on the floor? Scenes that look realistic are in fact slightly off. When asked, he says his paintings are not about realism, but reality.

He vowed in his 2013 memoir Bad Boy that “I would never let the unspeakable also be unshowable. I would paint what could not be said.” But today we live in a garish world where things are overshared. What can be the goal of his work in an age where everything is shown and said? “That’s a myth,” says Fischl. “It’s not true. It just appears that way.”

Fischl has said before that the subjects in his paintings have given up on a higher purpose. What about him? “I don’t know. I keep looking for it. For me the one higher purpose is to try to keep the empathy channel open. Speaking towards America, the lack of feeling for other people is phenomenal. The superficial look at my work would be that it’s a comment on or “critique” of something. But actually what I’m trying to do is look at something that is real. These people aren’t everybody, but they’re somebody. And if you can feel the confusion—if you feel tender towards them or compassionate towards them or angry with them or something—then the art’s doing its job.”

Images © Eric Fischl. Courtesy of Skarstedt