Photographer Eric Rhein’s monograph, Lifelines, has been a long time coming: work on its images began back in 1989, but the decades have done nothing to erode their potency and poignance. Rhein—who works across wire drawings, sculpture, photography and mixed-media collage—describes it as “an artistic experience as well as an historical document”, and these terms seem both piquantly apt and somehow also lacking in communicating the deeply moving, personal but universal vistas of Lifelines.

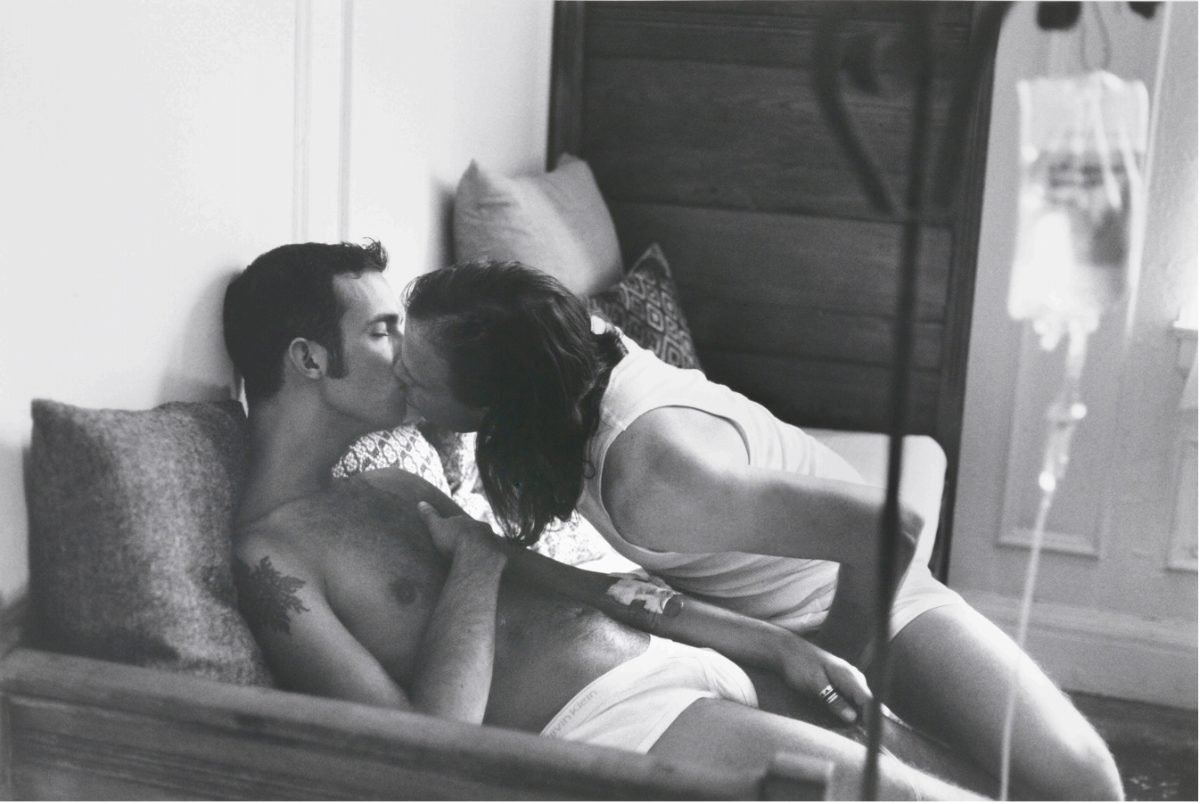

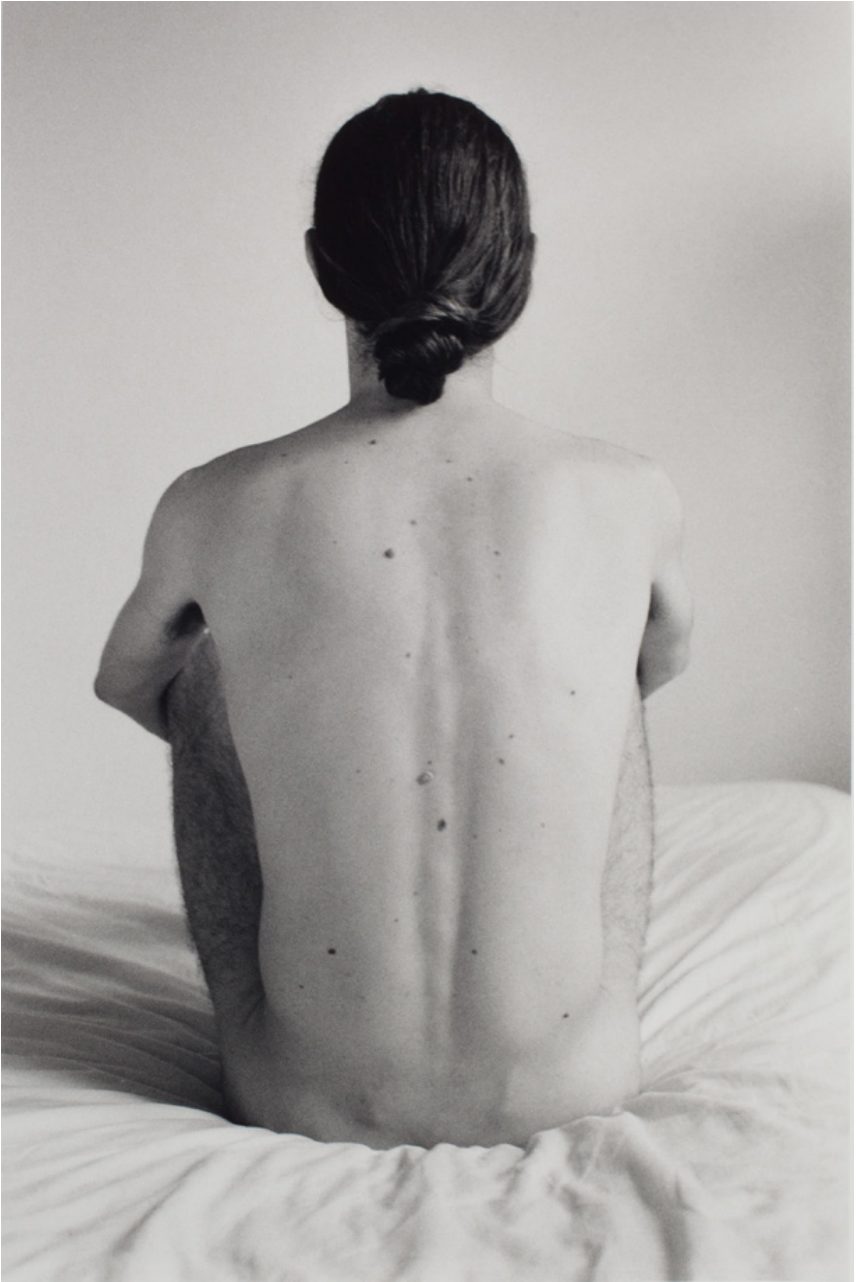

The monograph/memoir spans three decades of Rhein’s work, featuring images shot between 1989 and 2012, including self-portraits and images of his friends and lovers. The period of time is significant: it spans the years after Rhein was diagnosed with HIV in 1987, running through his near-death, and closing around the period he found “the eventual vitality that new medications would afford him”, as the book’s publisher puts it.

“Rhein sees his art as a form of activism and healing as much as creation”

Rhein was raised in New York’s Hudson River Valley, and during the 1980s was a fixture in the East Village arts community alongside the likes of Greer Lankton, Luis Frangella, David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar and Mark Morrisroe.

His work is largely inspired by his uncle Elijah ‘Lige’ Clarke, an activist who co-founded the first national gay weekly newspaper, Gay, and the Washington Mattachine Society, with his partner Jack Nichols. As such, Rhein sees his art as a form of activism and healing as much as creation; and is a founding member of the Visual AIDS Archive Project, which was formed to support artists living with HIV/AIDS and preserve the works of those who passed away.

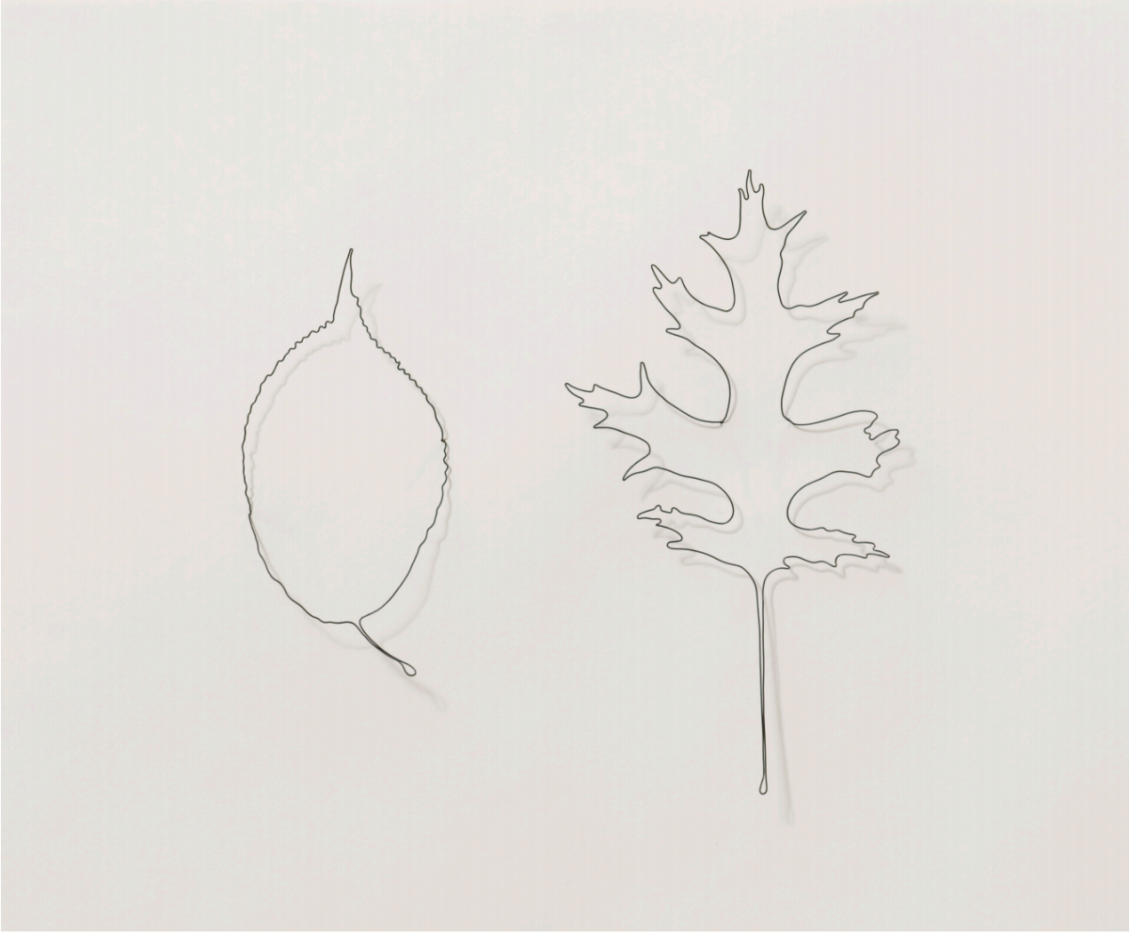

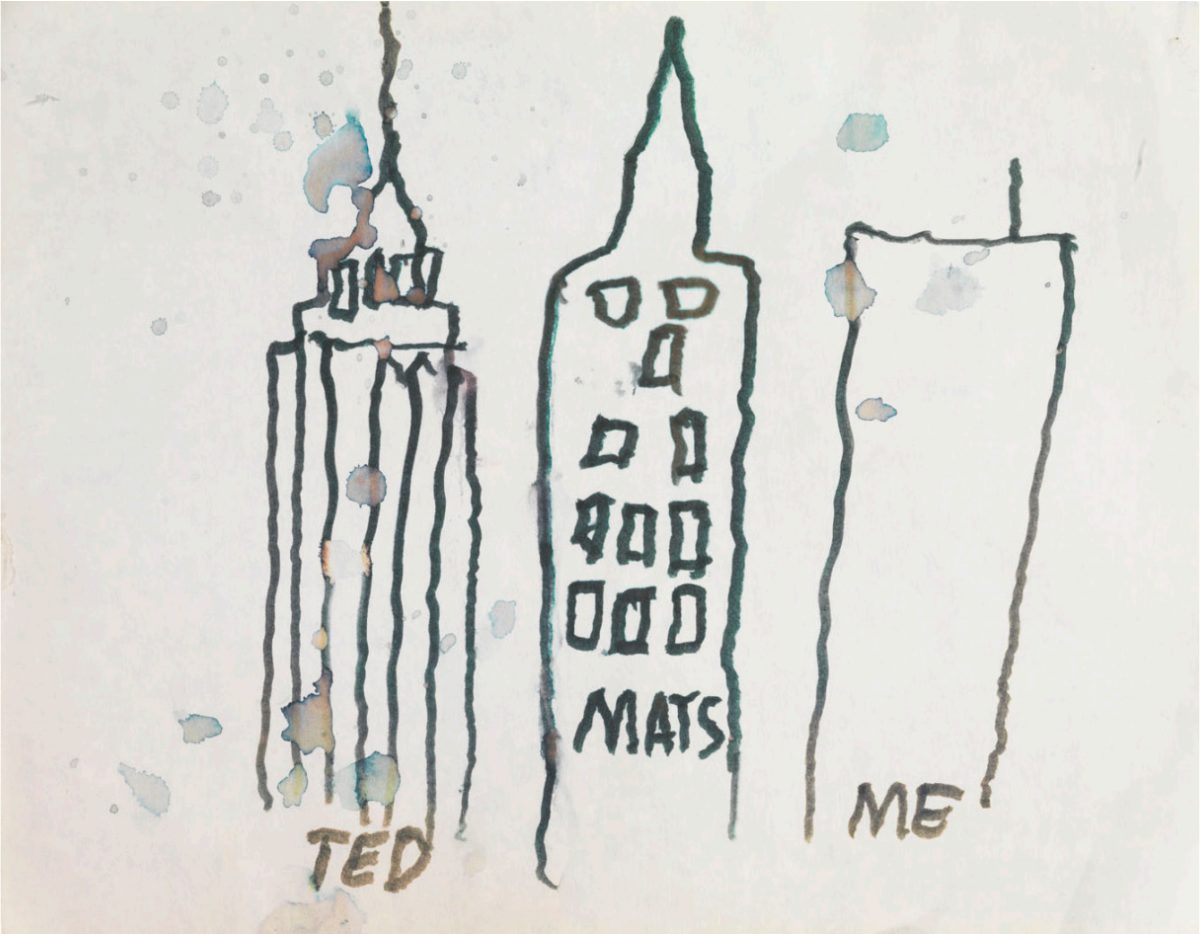

- Eric Rhein, Jeff and Tim (Jeffrey Geiger and Tim Goetz), from Leaves, an AIDS memorial, 2005 (left); Ted Mats Me (from Hospital Drawings, Saint Vincent’s Hospital) (right)

While there are multiple concurrent themes and lines of inquiry in the book and in Rhein’s work (nature looms large, for instance), its pulse point is a response to the AIDS and its impact. It’s about life, love, death and pain; delineated through images that feel vehemently tender. The intimacy that imbues his photographs is so potent that the viewer almost feels accidentally voyeuristic—that we’ve seen something that’s not for us, and it’s time to turn away. But their privacy gives way to the universality of tragedy and the agony of loss, and of the beauty of vulnerability, and just being alive.

As well as Rhein’s photographs, the book also includes essays by poet Mark Doty and publisher 193’s director Paul Michael Brown; as well as watercolours, assemblages and wire drawings, many of which are part of the artist’s ongoing project Leaves, an AIDS memorial honouring more than 300 individuals that he knew.

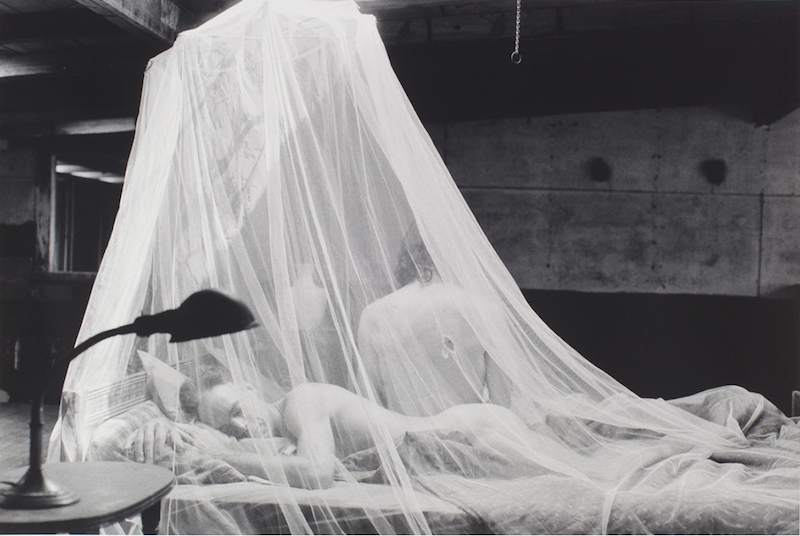

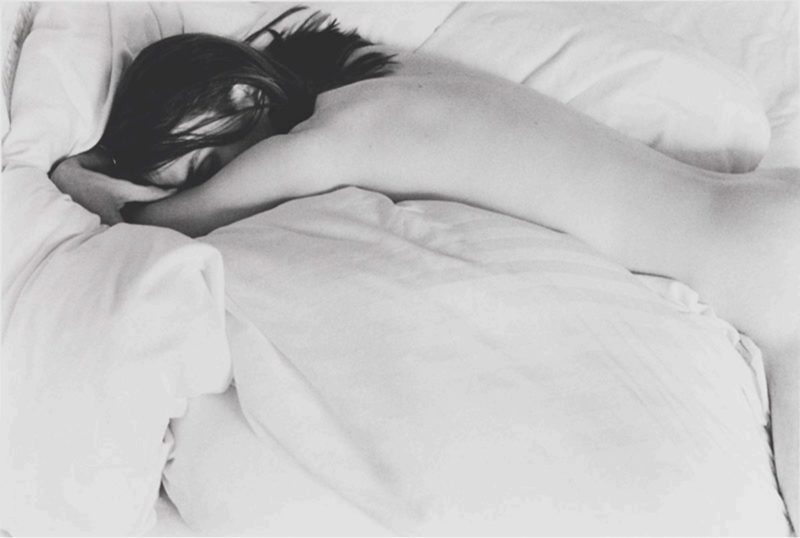

At times, Rhein’s images are as seductive as they are harrowing: his quiet, plaintive style is as beautiful as his subjects—mostly elegant young men shot in reverent chiaroscuro. The shots of friends and lovers underscore the vast chasm of “before and after” that the AIDS epidemic engendered: community and desire was soon to become solitude and danger. “The intimacy of sexual experience speaks to the most fundamental of human wishes: to be held, embraced in all the senses of that word, and to embrace another,” writes Doty in his essay.

“…We dwell for a time in that light. The self is held by an equally desiring other, and the self who can no longer embrace can be embraced just the same. No one disappears in the embrace, no one is swallowed up, and two selves make together a fullness outside of time.”

- Eric Rhein, Veil 2 (self-portrait with Russell Sharon, Hudson Valley) (left); Dodge–Before Dawn (William W. Dodge IV) (right), 1994