Ericka Beckman’s video works never fail to jolt: their lurid, neon-hued colour palettes adorn strange, frequently dystopian worlds in which there’s always a game, never a winner. Instead, we see our campily-costumed female protagonists trapped in futile, looping quests; bobbing about at the mercy of the desires of other people, or unseen structures and forces.

Her imagery is often inspired by the visual language of early computer games, subtly reflected in her characters’ movements, and overtly underscored in the grid structures and flashing text that offer a framework of sorts to her non-linear narratives. Just as you feel you’re making sense of her stories, you realise that you don’t have to: her tales critique a world in which structures such as those of the patriarchy are inherently ridiculous and nonsensical.

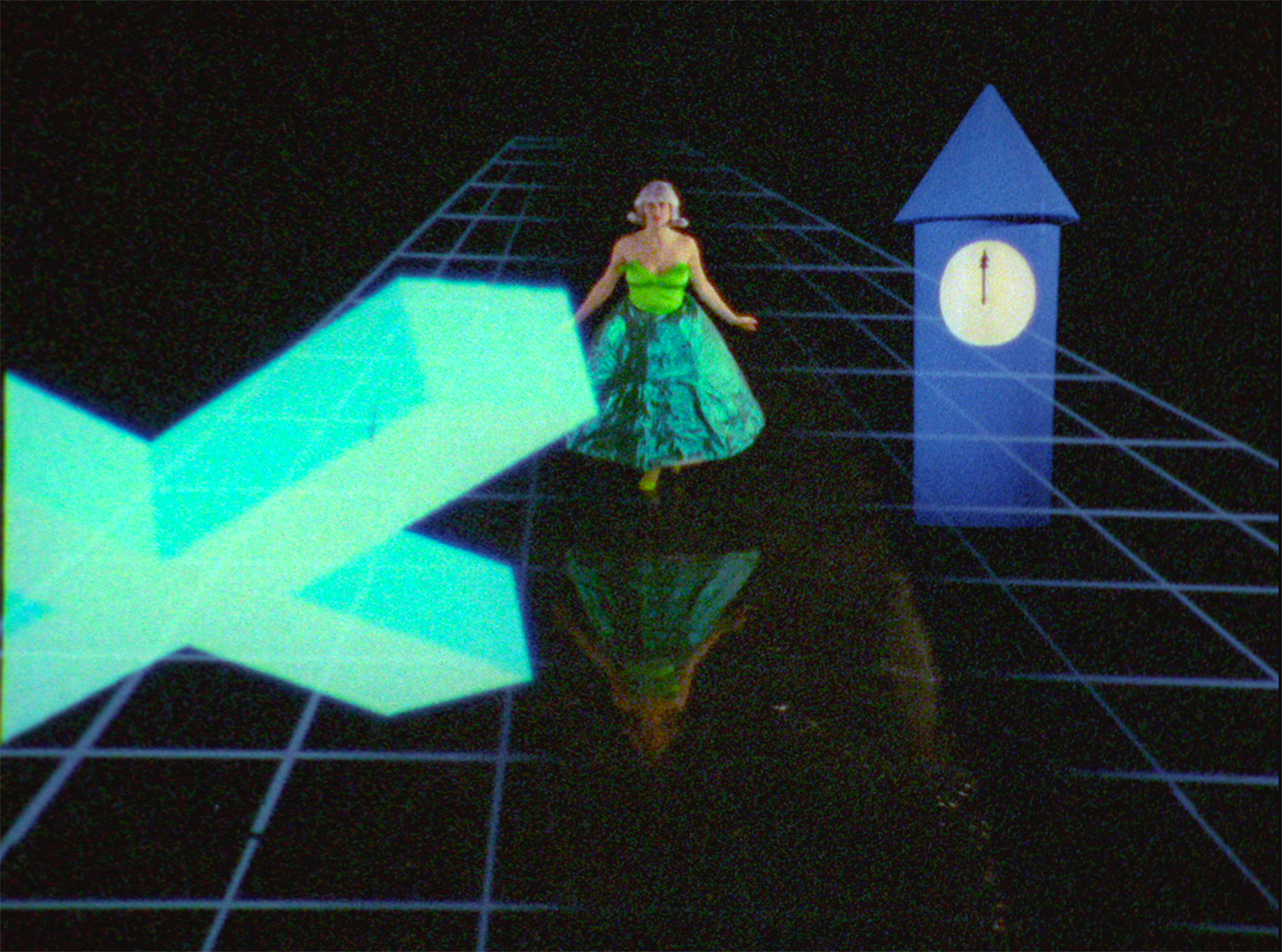

Cinderella (still), 1986

The artist began to make films in the 1970s as part of the group of largely CalArts grads later dubbed the Pictures Generation; and says that early in her career, seeing the emergence of music videos was “the first time I saw experimentation with image and sound and the form itself as being something which excites you to get up and move.” She went on to work with artist Julia Heyward on Talking Heads’s Burning Down the House video. As such, her work is driven as much by its strange and compelling sound design as her equally strange images.

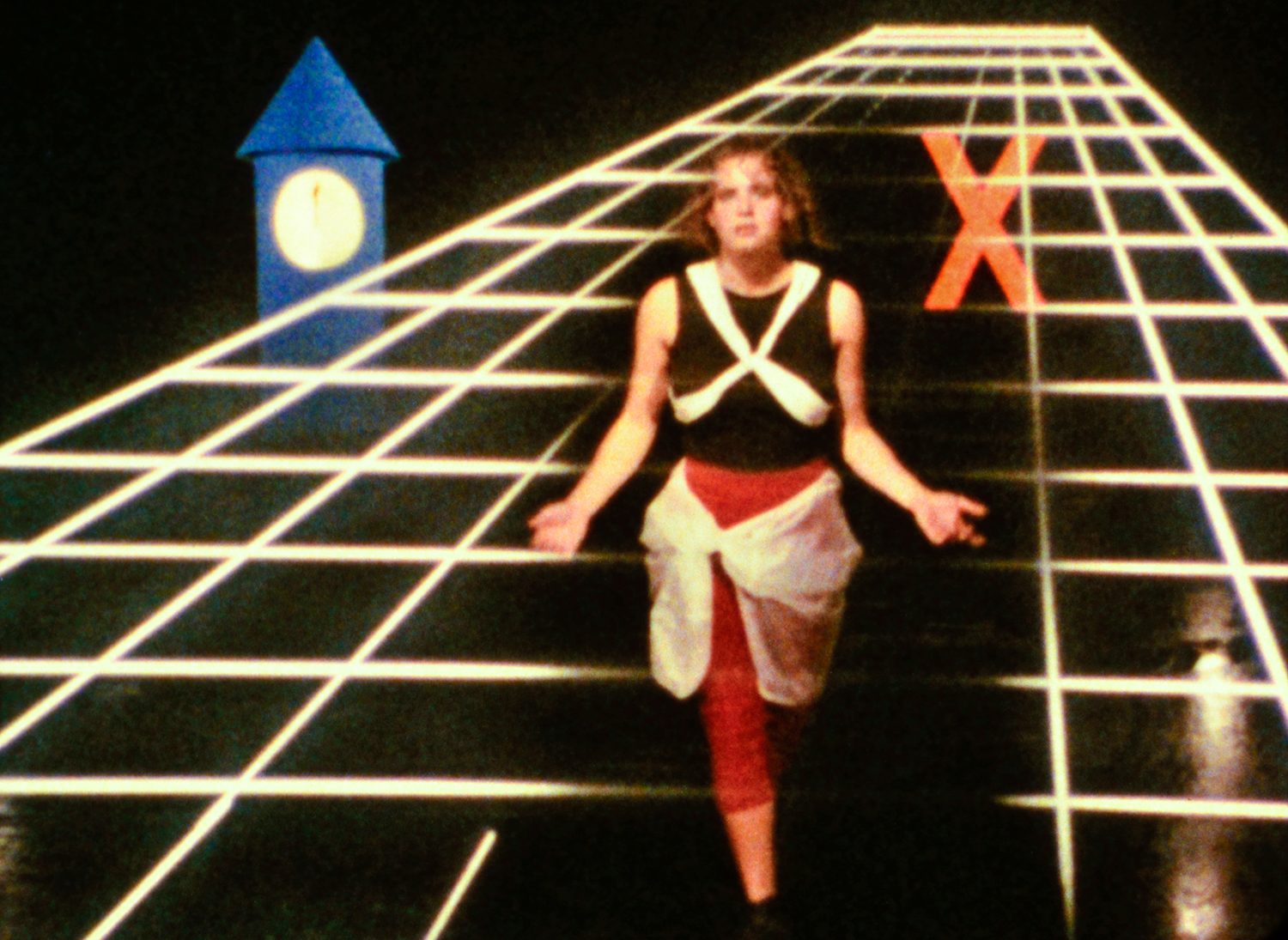

Two pieces of Beckman’s work, Cinderella (1986) and Hiatus (1999/2015), are currently on show at Fact Gallery in Liverpool. The pair of works are united by their roundabout explorations of female identity in an post-industrial age, grappling with both traditional gender expectations and the emergence of virtual landscapes. The “real” and the “digital” become confused; and in Hiatus in particular, we see the conflict (and irresolution) of the dual impulses for idealism and corruption offered by the then-new world wide web.

You frequently make use of sound, and most of all percussion, in your work. How do you approach those elements?

It is important for sound in film is to engage the body and the senses—not through emotion, but in a direct physical way—to feel a physical extension of the actors and the material and also the editing, and the kind of jarred juxtaposition of things. I went to CalArts to learn percussion in order to work with musicians; to collaborate with students in the music school and directly involve people that were making music into the collaborative process of making image and sound together. I want people to feel that my work is a part of them—not just cerebrally or emotionally but hopefully a feeling of some kind of interaction.

That idea of interaction is central to the idea of a game, too, which a lot of your work explores.

Game structures were something for me to hang on to while I was working linearly with time, and trying to avoid autobiography and narrative. The lineage of my work starts with surrealist games and situationist art practice in the late 60s. What I took from performance in the late seventies and early eighties was that it was easy to develop ideas that are based on narrative in gaming structures, as they hold an awful lot of the same attributes: there’s competition, there’s equilibrium and balance, protagonist and antagonist, solo and group work, strategy-building… If you break down the narrative, you see those elements. The game itself is a backbone in some part of a narrative structure, so I was looking at where they coexist. I did a lot of research in order to be confident in using game as structure, so I researched games through culture and through time and early on discovered it would be the thing that would be with me for a very long time.

“I want people to feel that my work is a part of them—not just cerebrally or emotionally but hopefully a feeling of some kind of interaction”

- Ericka Beckman, Hiatus, still

- Ericka Beckman, Hiatus, still

Why did you choose the Cinderella story for your work?

Because there are so many variants of it. I read two anthologies of the story, and there are easily 400 entries. There was a real search on my end to find a woman’s story. I was dead set against using Cinderella at the beginning, because it’s such an overused symbol— it was so offensive to me. But I was committed to the idea that I’d find a fairytale that had enough cultural diversity in it that I could generate a version of it that would react to the most common one we know: that Disney one.

It’s a story about waking up and belonging; where you fit in the world. It’s always about economic downturn, whether that’s being in a fatherless family and having to work or being abandoned and having to work. A lot of the characters in some versions of the story had to disguise themselves as young men in order to survive, so in my film it’s about the importance of the costume as a disguise.

Do you see Cinderella as a feminist piece?

That’s a very interesting question. When it came out [in 1986] we’d just had a huge feminist surge culturally in the early eighties. In my generation and group of people in New York, people like Lizzie Borden and Kathryn Bigelow who were trying to participate in an alternative cinema scene upped and went to Hollywood, thinking that if you wanted to be involved in change you had to be in the “real world”; there was that divide. I was pretty much committed to staying with what I was doing and not changing, but I wasn’t interested in theatrical distribution.

The film hit a chord. When it came out the feminist critique of it was that it was undermining feminism because I was using musical tracks—I was doing a musical using a broadway singer, and the fact I was turning feminism on its head by using the musical genre was pretty much the immediate reaction to it. No one confronted me at the time, but my friends would hear people talk about it, saying, “You know it’s not a feminist film, it’s not in the tradition of feminist work”. But my intention was not to make a feminist film in any case: it’s about freedom and free will rather than being tied to gender.

“At the core of my work there’s always something that really offends and disgusts me”

- Ericka Beckman, Hiatus (1999/2015), installation view at Fact, photography by Rob Battersby

- Ericka Beckman, Cinderella, installation view at Fact, photography by Rob Battersby

What’s interesting about the games you depict in your work is that there’s never any “winning”—characters seem sort of stuck in a futile loop. Why is that?

Because I’m more interested in the process of confrontation and adjustment than competition or defeat. Our culture now is so bogged down with “gamification”: from what I see, there are a lot of cultural products that are using game strategies to motivate consumption, and in some cases, education. I see these strategies as being one aspect of gaming, but for me the interest is in analysing the rules of the game and the systems and strategies, and confronting and adjusting them. I have to really untangle the process, and show it in repeated attempts and looping in order to focus the attention away from the goal and on to the process.

At the core of my work there’s always something that really offends and disgusts me. I take that impulse, or a concept I struggle with, and work it out in the film. The work has to start from some emotional charge, usually a reaction.

Ericka Beckman is on show with Marianna Simnett at Fact, Liverpool, until 16 June

VISIT WEBSITE