Kessels has published over fifty books of his collected images, including the vernacular photography book series In Almost Every Picture (2001–16), and since 2000 has been an editor of the monographic magazine Useful Photography

, focusing on overlooked images taken for practical purposes. The work is loaded with love and humour but there is also a deep melancholy to it—the approach, to borrow Tibor Kalman’s term, could be called “contemporary anthropology”. By detaching images from their original context and changing the way in which they are viewed, Kessels gives us a magnifying glass to look at ourselves in a different way. This recontextualizing of found photographs is at the heart of what Kessels does so successfully. As Marcel Proust said: “The true voyage of discovery does not consist of searching for new landscapes, but of having a new pair of eyes.”

As someone with a commercial background, how were you initially received in the art world?

My first exhibition [in 2007] was a very big one. It filled nine halls! I always thought that there would be criticism from the museum and art world. But it turned out to be the other way around. The art world had no problem with my background whatsoever; it was the advertising guys who didn’t really understand it. It’s a bit understandable because it becomes hard to choose what title to use for yourself. It’s a great luxury to be able to work across so many disciplines. I’m always hoping that labelling yourself will be unnecessary in the future.

What was your reaction when you found

out about the nomination of Unfinished Father for this year’s Deutsche Börse Foundation Prize?

I had been on the shortlist a couple of times before, but it was really special to eventually be nominated with a project as personal as this one. Unfinished Father is about my father. It shows a small, unfinished Fiat Topolino and the Polaroids my father took during the renovation of it. My father suffered a stroke and will never be able to finish his car. For me the car became a symbol for my Unfinished Father. It’s the personal story behind the otherwise random pictures that makes it so meaningful. It was a great honour that the Deutsche Börse Foundation Prize saw and recognized that.

I read in an interview that you were pleasantly surprised a few years ago when Mishka Henner was nominated for his project No Man’s Land because “that was not typical, not the usual finalist, and marked an interesting shift”.

It’s good to see that the more experimental projects, movements on the border of photography and art, are getting noticed.

How do you reinterpret and give a new meaning to found images?

By selection and curation you can enhance an existing story. You never alter the images or create something that wasn’t there already but you can magnify it. It’s always very important to leave space for people to have their own interpretation—that way one plus one becomes three. You create an opportunity for people to pause and take a moment to discover something new.

Does the magnification of reality create new fictions?

Well, you could see it as a distortion of reality but you could also see it as magnifying reality by making it bigger. I try not to distort reality but some things that I do are not totally real, there is a slight percentage of fiction in there. I try to make people look at things in a different way. And to relook at it in a different way. By not distorting the content or the pictures themselves, I try to keep it very authentic—I simply edit or bend the story a little bit. Nowadays an average person sees more images before lunch than someone from the eighteenth century in their whole lives. This new phenomenon has made us a species of editors. There is so much available that we have to choose what we see, what we hear and what we read. Because of the internet the role of photography has changed. The average lifecycle of an image has become much shorter and the physical aspect of the images has disappeared. The abundance of images has sparked a new kind of photographic practice. It’s no longer needed to take images of your own now that there are so many available online for the taking. There’s a lot of people copying each other, making pictures of their food and their feet. The stories and ideas behind the photos have become more important. We live in a renaissance of imagery today—there are more images than ever. The phenomenon of reappropriation is a result of this. I react to this and work with it.

Which other artists influence your work and why?

I love the work of Joachim Schmid and Hans-Peter Feldmann. I’ve always been fascinated by the way artists appropriated existing images and the story they were able to tell by doing so. Like Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and Christian Boltanski. I love Warhol’s Double Disaster, in which an ambulance is involved in an accident. And Boltanski’s Kaddish, a deeply moving book filled with just images and no words. To me it’s an example of how much you can say with just images. My personal playgrounds are the two series that I make, Useful Photography and, in particular, In Almost Every Picture. They are storytelling books. My background as a graphic designer and an art director—where most images are kind of perfect—has fuelled my passion for found and amateur images precisely because of the imperfection in them. We live in a time where imperfections are harder and harder to come by. Everything is corrected, Photoshopped and polished. Logically there is a reaction to that. An old picture becomes interesting again and vinyl is gaining popularity because of the authenticity of it. But now “authenticity” is becoming a tool to create the perfect imperfection—with Instagram filters, for instance. It’s a shame so much of it is fake.

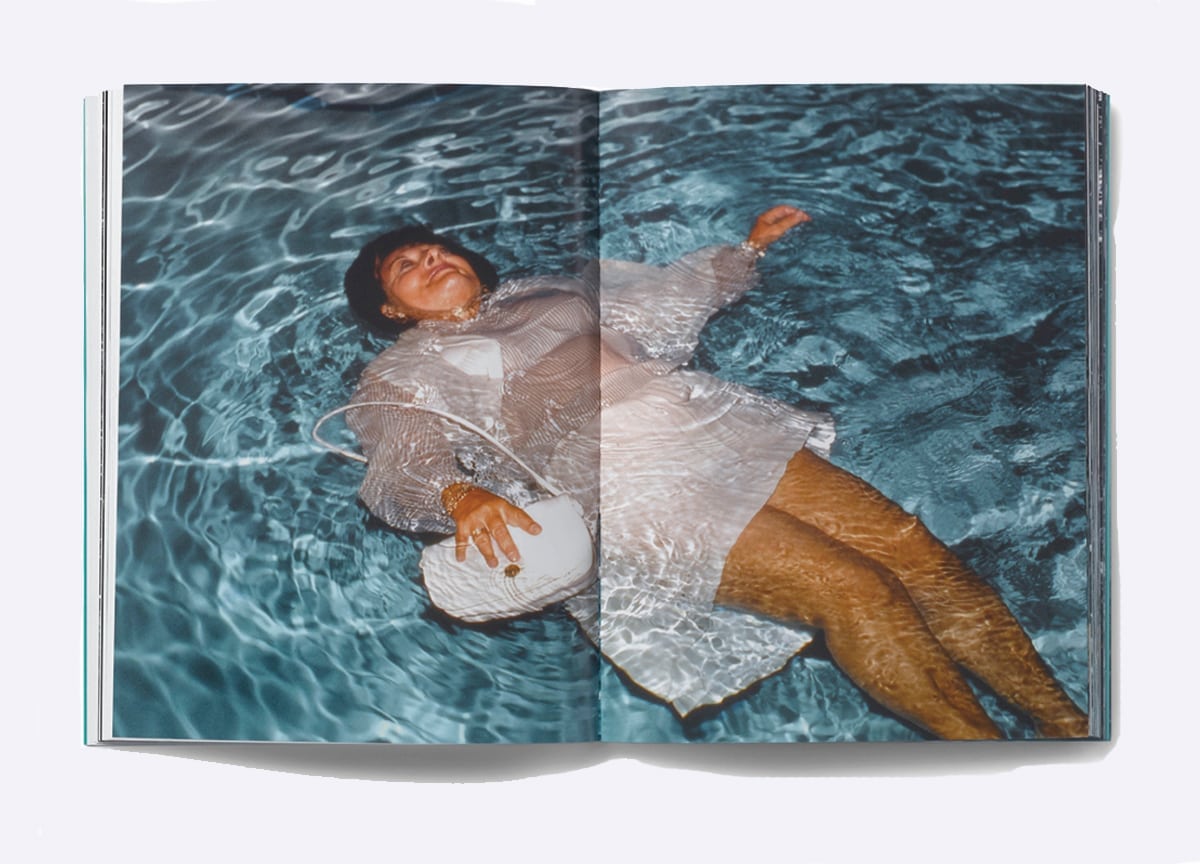

The internet,in particular networking and image-sharing sites,has brought about a fascinating voyeuristic phenomenon. What used to be private has become public.

Exhibitionism has always been there, it’s not a new phenomenon. The internet has only sparked it and made it more accessible. Take Fred & Valerie (In Almost Every Picture 11), for instance. Their sweet and special fetish is something that we would never have come across if it wasn’t for the internet, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t exist. The internet surprises us, it showcases the things that otherwise stayed in shoeboxes at the bottom of a closet. And yes, it has shown us that apparently a lot of people don’t really have a need for privacy.

“for me images are nothing without the mysterious patterns they sometimes make”

Your travelling exhibition, 24 Hrs in Photos, is a colossal and poignant display of the unstoppable surge of digital imagery.

There is an overload of images in this digital era. I wanted to see what would happen if I took all these images offline. It puts our daily use of images in a new perspective. Also it created this weird and beautiful tension between private and public use of images.

Can you describe this “beautiful tension”?

Privacy is hard to find on the internet. We had family albums before, and they were very secret, for private use—nobody else could see them. This happened in In Almost Every Picture 1: the private travel photographs became quite public. Reversing the roles changes the point of view. But on the internet there is a blurring between the private and public. It is almost obscene. You can see everything. I mean, when a baby is born people put it on Facebook and everyone can enjoy the bloody picture of the baby being born. It’s absurd. In 24 Hrs in Photos people actually walked over the pictures, and some of the pictures were very private and intimate moments. I find it fascinating to play with the private and public.

Besides the fact that the images were all shot by amateurs and how disparate the topics of the books are, the nature of the stories is similar.

A lot of the books are about life, death and the passage of time. For example, in In Almost Every Picture 1, Rosario, the woman in the pictures, gets smaller and smaller as the sequence progresses. Through the years, her husband took more distance from her, becoming more interested in the surroundings, or maybe it was her—she didn’t want to be photographed up close any more. The book is almost like a flipbook—Rosario becomes smaller in the landscape. It is beautiful but also tragic and sad in a way.

“The art world had no problem with my background whatsoever; it was the advertising guys who didn’t really understand it”

Regardless of how tragic or sad some of the stories are, there is an irony and a humour in the telling that makes them almost grotesquely funny.

Yes, definitely. In storytelling you need a certain kind of curve. For instance, in the book with the rabbit, everyone laughs and thinks that these pictures are very funny but at the end there is a totally different experience because you see that the rabbit is getting old and is dying. At the very end there is an image of two carrots placed in the snow as his tomb. This is a classical curve of humour, tragedy and humour again. This works in storytelling.

Which part of your working process excites you most—the search for the images or the search for unseen patterns?

Unseen patterns, because that’s the real treasure hunt. It’s like visual archaeology. For me images are nothing without the mysterious patterns they sometimes make.

How does your advertising/commercial work inform your personal work and vice versa?

Sometimes I search for amateur mistakes in my commercial work. Because I believe that professionals can learn a lot from amateurs and vice versa. The ‘off’ moments in photographs are often more interesting than the perfect ones. For Diesel we were able to use a picture with a model looking very funny instead of beautiful. It just makes you look at the ad a little bit longer.

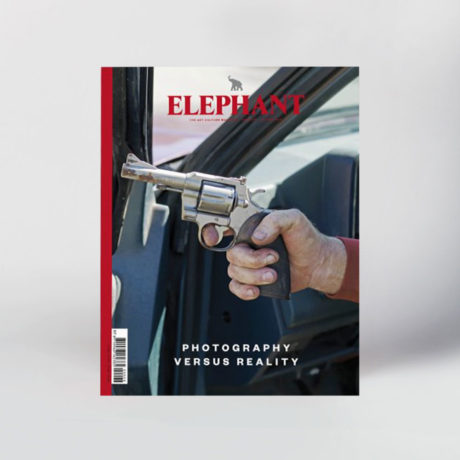

This feature originally appeared in issue 28

BUY ISSUE 28