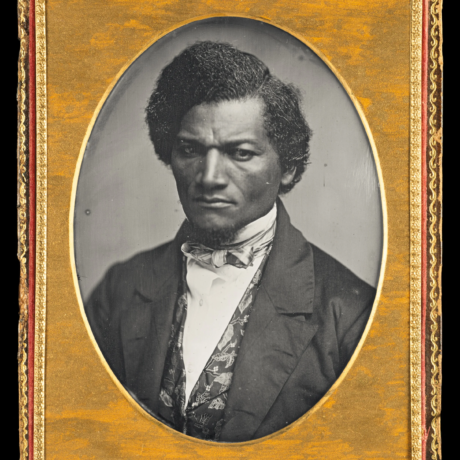

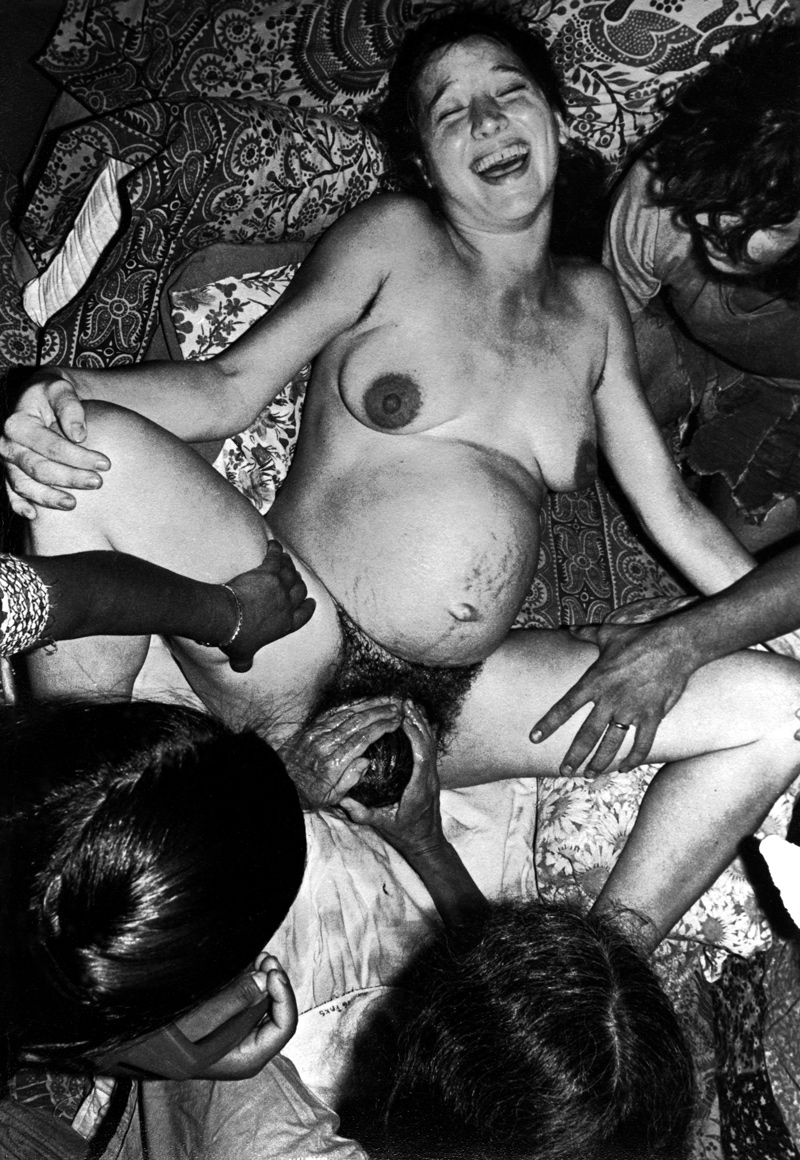

The fact that you can orgasm while giving birth is perhaps not as well-known as it should be. The artist Hermione Wiltshire reminds us of this fact in Therese in Ecstatic Childbirth, a response to the censorship of positive birth images, a picture that was originally taken by radical midwife Ina May Gaskin of a woman at the point of crowning. You might think that this is exactly the kind of image we would want to see: a pleasurable picture of birth. To look at it might bring confidence and relief; more universally, it reminds us that even in intense pain, there can be joy. But the image hasn’t proved very popular; it has been repeatedly censored and removed from public display. Not only are women not supposed to enjoy childbirth, but the image patently represents one of the most unbearable things we can imagine: the sexuality of a mother.

Obstetrical orgasm—what Terese apparently experiences—is a relatively rare medical phenomenon. Only around 0.3% of women, it’s estimated, will orgasm during birth. The physical experiences of pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding put you firmly back into a female body in a way that can be strangely erotic. But, outside of niche pornography, this erotic feeling evolves over time into a shameful kind of sexuality. No-one wants to address the idea of what critic Susan Fraiman, named the “sodomitical mother”, in other words, a mother with sexual desire to spare—beyond the required amount needed to reproduce.

“The physical experiences of pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding put you firmly back into a female body in a way that can be strangely erotic”

In the contemporary visual world, depictions of pregnancy and breastfeeding have done a lot to eroticize and heroicize female bodies; flaunting their rounded fullness. We could interpret this as celebratory, but the eroticization of motherhood is contradictory: you can be sexy in a passive way, but when a mother figure overtly expresses sexual desire it becomes disturbing. Why are so many people, for example, squeamish about public breastfeeding? We cannot stand the proximity of sex and motherhood, though they come from the same primal desires. Think of Halley, the mother in The Florida Project, who seems driven by sexual desire and seems to enjoy using men for sex and money. She’s hardly a sympathetic figure, choosing a lifestyle that clearly isn’t good for her daughter. Sex isn’t Halley’s only issue, but we are encouraged to be shocked by her sexuality.

Society demands we separate active sexuality from motherhood, because we cannot bear the thought of it. Psychoanalysis has made us all afraid of the sex lives of mothers, and what it might say about us. As the novelist Catherine Texier wrote, in 2000, “perhaps it’s time to open the door on the secret, sexual lives of mothers, even if it is hard for children—and we readers have all been children—to contemplate this taboo: our own mother’s sexuality”.

“Slowly my sex drive has returned, but there are times that it still feels a little bit wrong”

When I became a mother, my sexuality shifted: for some months after birth, sex was the furthest thing from my mind and the last thing my body needed—both were occupied with another kind of physical love. All my sexual feeling was lost in a cloud of nursing pads and pillows, muslin cloths and wet wipes. Slowly my sex drive has returned, but there are times that it still feels a little bit wrong—the guilty pleasure of literal pleasure. Modern motherhood wisdom will tell you to take “me time” and practice self-care, but when it comes to postnatal sex issues, between the “MILF” videos and Mila Kunis in Bad Moms, it’s all very murky waters.

I’ve turned to photography, again, to find some space to contemplate this awkward question. You cannot forget you’re a mother; it becomes part of your sexual identity as much as the rest of who you are. The works of Berber Theunissen juxtapose a mother’s nurturing sensuality and beguiling sexuality, exploring fleshy nudity,

gauzy curtains, bedsheets, morning light. Partner and newborn child are shown with love and affection, different but equal. None of it is shameful. The Dutch artist, who is represented by Open Doors gallery, extends the eroticism of this transformative phase in a woman’s life, changing bodies, the renewed sense of feeling for the world, into early motherhood and family life. It’s like a warm, fuzzy, all-encompassing embrace. The love between a family emphasizes, rather than diminishes, a mother’s innate sexual power.