Conservative British politicians excel at crafting images of prosperity that stand in inverse proportion to the country’s economic realities. A common method involves embedding glorified yet easily consumable versions of patriotism within everyday situations. For example, a builder’s brew poured into a Union Jack mug, or the proliferation of the monarch’s image on everything from T-shirts to scatter cushions.

While these customs stand at the root of unequal policies, discrimination, and class division, Britain is still one of the most prosperous countries in the world, as long as we separate macroeconomy from society. It is a distinction these politicians expertly blur.

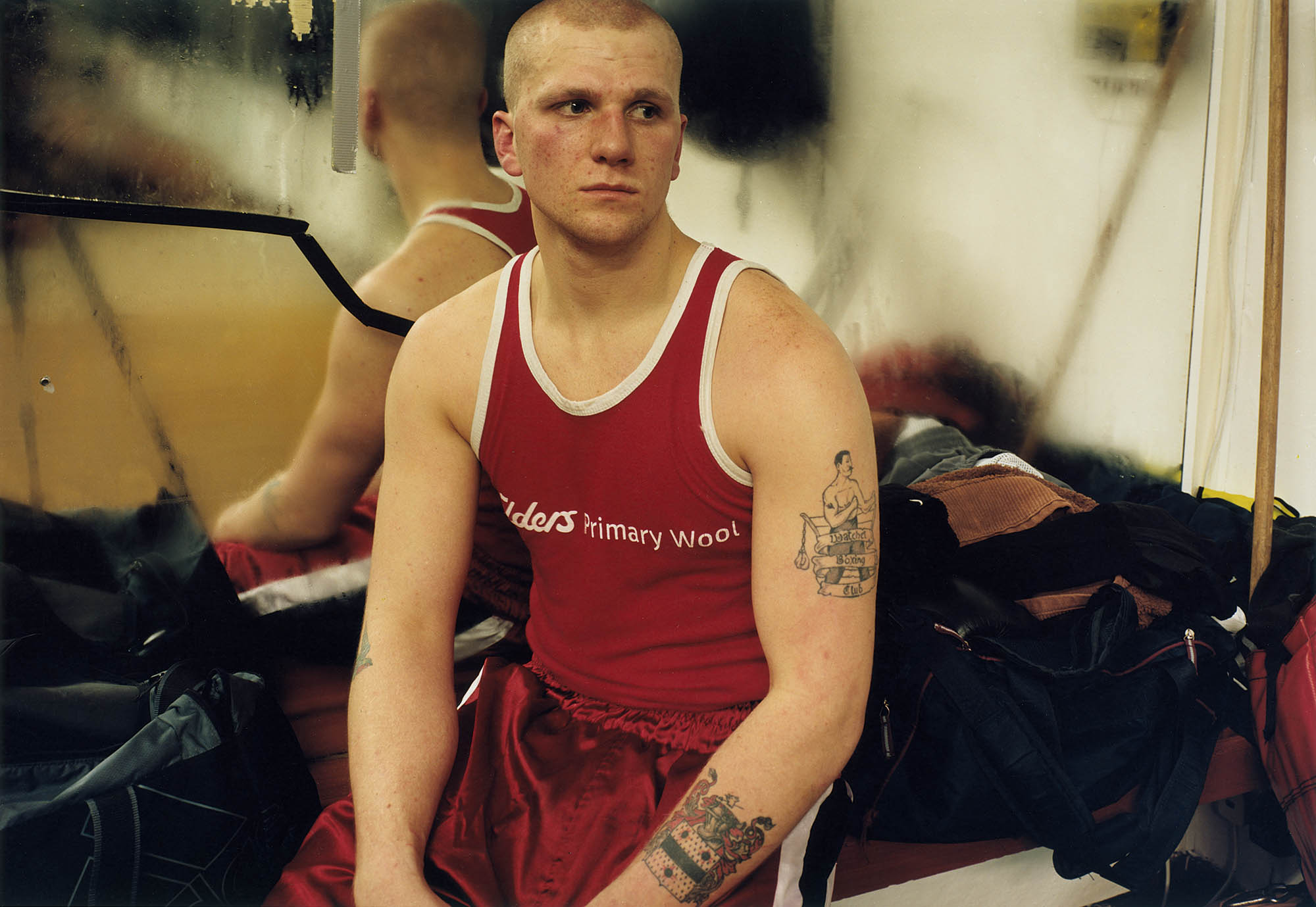

Tim Richmond peels back the veneer in his photobook Love Bites. It captures life on a twenty-mile section of the Bristol Channel that tourists sidestep in favour of the more picturesque destinations of Devon and Cornwall. He composes his scenes with a painter’s sensibility but relies on the photographic process of bleach bypass development to obtain high contrast and slightly desaturated colours. The result is an aesthetic bleakness that is probably more pronounced than any actual visit to the area.

The images were made in pubs, clubs, bingo halls, and cheap eateries, their artificial light imbuing them with a cinematic look that colours the struggles of the regulars that frequent them. Even the exteriors have a gloomy psychological charge, starting with the shoreline, arrested in various shades of grey that may explain the lack of tourists. Humour is present, albeit in small doses, as seen in a snap of graffiti that reads “Big Up Isambard Kingdome Brunell” accompanied by a sketched face wearing a top hat.

“Documenting the shortcomings of a place is not sexy or fashionable, but Richmond’s depiction of the working class is incisive but respectful”

The book also gathers images of cultural staples, namely canned beans, chips, darts, Harrington jackets, chequered shirts, and Doc Martens, along with food banks (a more prevalent addition to the British lifestyle in recent years). Richmond’s pictures witness the fate of people with low-paying jobs condemned to poverty, many of whom are immigrants working in hospitality, or as food pickers and truck drivers.

While the images offer only a glimpse into these people’s lives, their unhappiness is palpable, and their physical exhaustion a reminder of how Brexit has affected those who struggle the most. The cast of characters is complemented by pole dancers, drifters, wrestlers, and boxers. Several transvestites also make an appearance (the book opens with the striking picture of a bewigged man in a dress aiming an air rifle) many of whom attend a local camp where they can holiday at ease.

“Richmond’s pictures witness the fate of people with low-paying jobs condemned to poverty”

The buildings of the different coastal towns show their own kind of exhaustion, with no sign of promised redevelopments happening any time soon. The closest we get to any sort of ‘levelling up’ is a new housing complex for workers at the Hinkley Point nuclear power station. However, the site comes across as just as soulless and generic as the prefabricated houses overlooking the estuary encountered on the following page. Other pictures show the dispiriting qualities of institutional décor in the waiting rooms of homeless shelters, rehab centres and other locations.

Photography allows a flow between certainty and uncertainty. It usually means that the questions an image produces outnumber its answers. The connecting thread running through this book is a collective lament for those who never enjoyed the glory of the Empire but must endure the “cost of living crisis” exacerbated by Brexit. Given the context, it’s hard not to interpret the lone slice of cake behind a café counter as a metaphor for the crumbs left by the one percent and its enabling system.

Documenting the shortcomings of a place is not sexy or fashionable, but Love Bites is not aiming for facile recognition. Richmond’s depiction of the working class is incisive but respectful, operating just like a love bite, an act of intimacy that leaves a visible mark of injury, which in this case consists of raising a mirror to reflect the harsh economic reality of disadvantaged communities. Anyone offended by Richmond’s love letter to the Bristol Channel probably doesn’t want to accept what is standing right in front of them.

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer and writer. He holds a PhD in Fine Art from the University of Oxford

Love Bites by Tim Richmond is out now (Loose Joints)