The visceral, boundary-pushing works of Eva Hesse and Helen Chadwick become sites of solace and self-reckoning in Ryann Donnelly’s Body High: Death, Drugs & Eva Hesse. Deborah Nash explores both artists and the themes of health and illness in their lives and practices.

In her book Body High: Death, Drugs & Eva Hesse, the author and artist Ryann Donnelly charts her disintegrating relationship with a heroin and crack addict. In a telling detail at the start, she comes across his druggy bag: “I found a tiny bit of plastic with a knot at the end of it on my dresser” she writes. From then on, the couple freewheel between cities and places to stay, from London to Venice, Marrakech to Los Angeles, between rehab and relapse. Threaded through the chapters are Donnelly’s encounters with artworks by female artists whose starting point is the body, whose art she sees as a form of self-care that gift her some respite. Their works “made me feel light and medicated: a body high.” Prominent among these is the German-born American sculptor Eva Hesse (1936-1970).

The final sculpture made by Eva Hesse towards the end of her life is displayed at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Baling out of the ugliness of her situation, Donnelly takes herself off to the French capital, seeking refuge at the Centre Pompidou where she stands before Untitled (Seven Poles) for an hour.

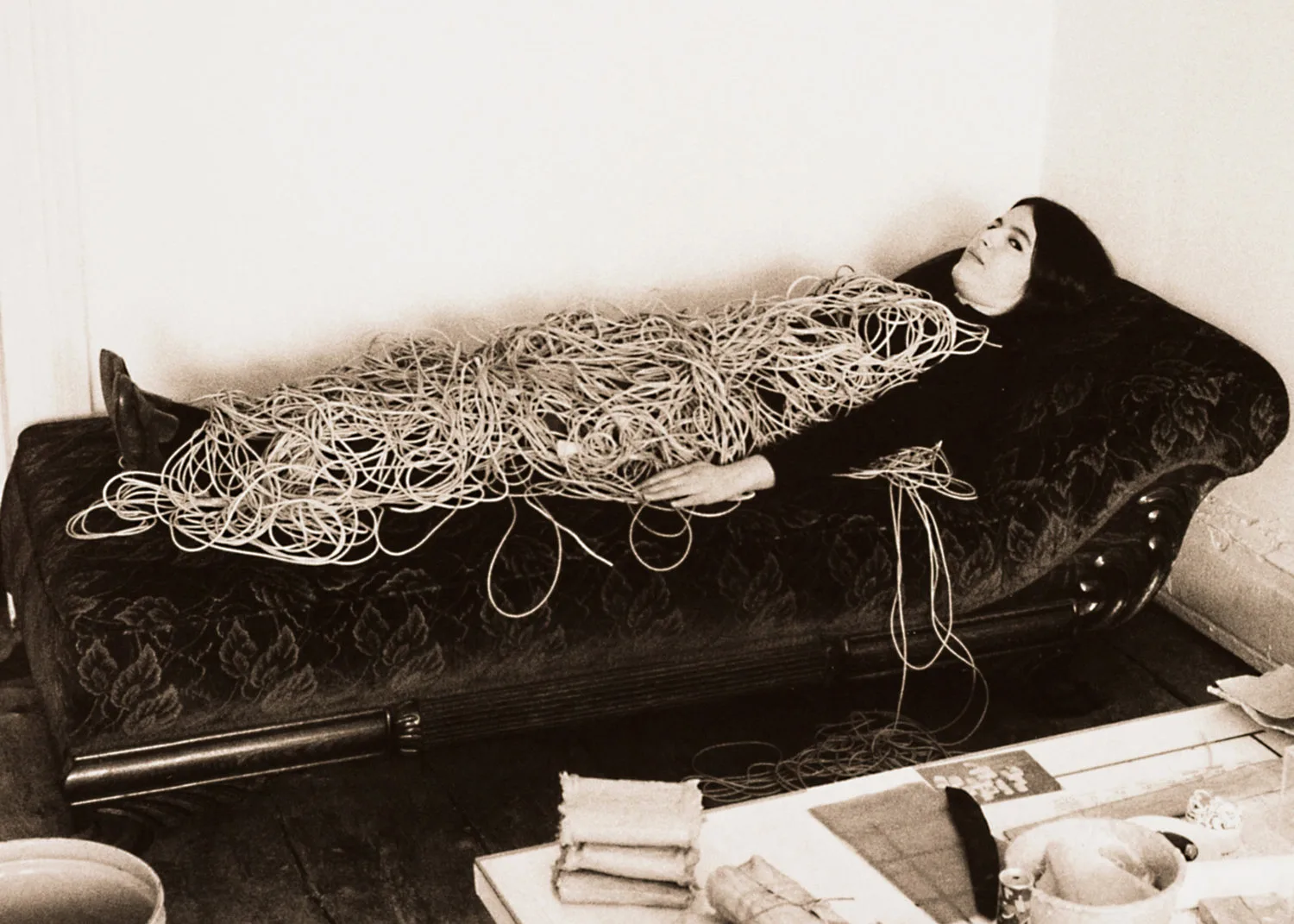

Begun in March 1970 and – following Hesse’s hospitalisation – completed by assistants from a maquette, then exhibited in New York in May (Hesse died from a brain tumour a few weeks later at the age of 34) Untitled (Seven Poles) is a wormy thrust of seven knuckled growths that kneel on the ground while suspended from the ceiling by wire hooks. For all the simplicity of their forms, the individuality of each upright is rooted in human corporeality, even recalling the etiolated figures of sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Their contact with the floor reminds me of Lauren Elkin’s anecdote that Hesse ‘couldn’t sleep at night without her feet touching the bottom bars of her bed frame’.Constructed from fibreglass, polyester resin, polyethylene and aluminium wire, Seven Poles glistens; its surfaces are a variegation of transparency, translucency and opacity. Donnelly is attracted to this material tactility, “its spermy, comey” eroticism, noting that the rubber, latex and plastics Hesse used draws associations with condoms, diaphragms, sex toys and fetish wear.

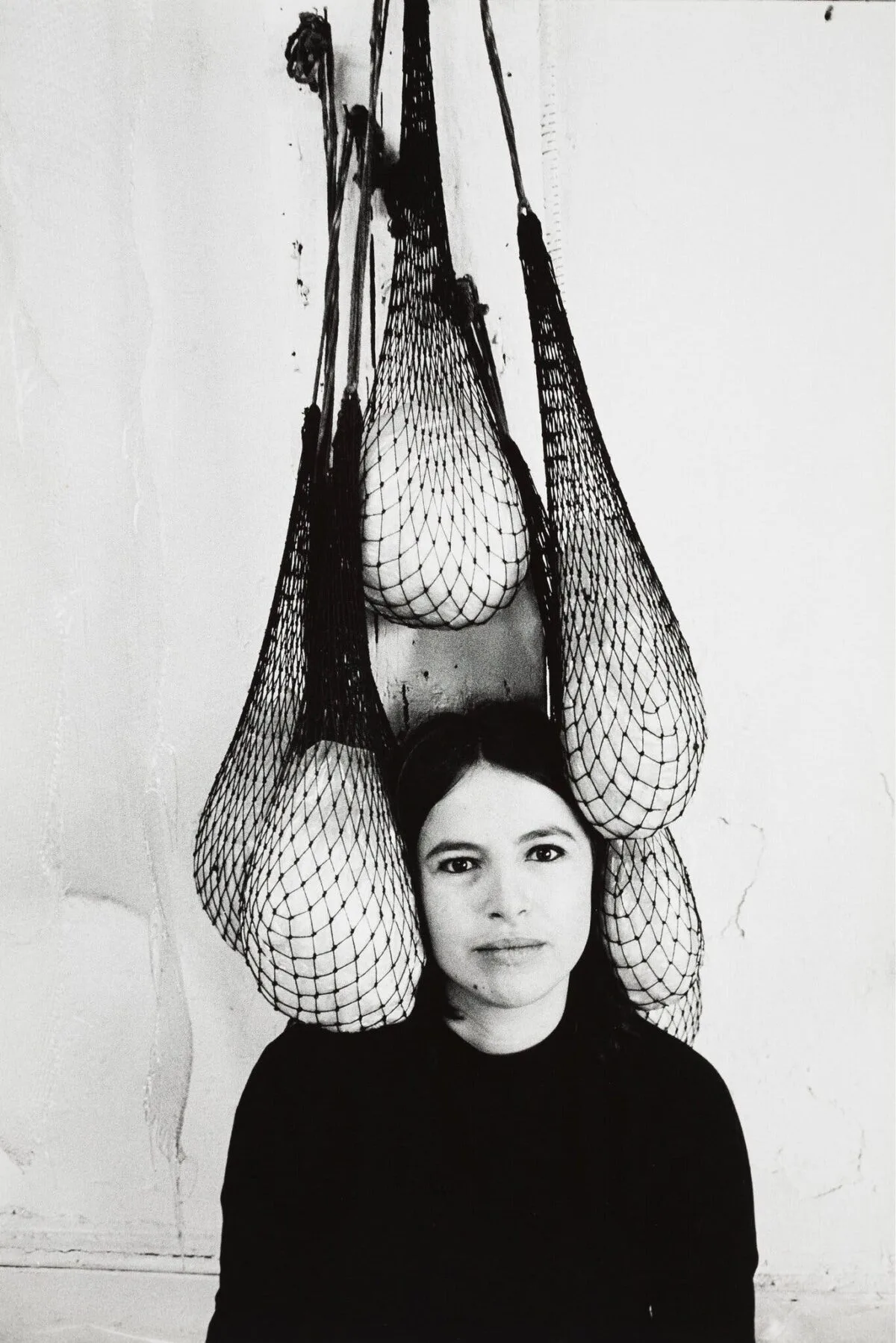

Eva Hesse was born in Hamburg in 1936 to Ruth and Wilhelm Hesse, a lawyer. When she was two, she was moved with her sister Helen to the Netherlands to escape the Nazis. A year later, the whole family relocate to New York and Hesse becomes an American citizen. Life does not go smoothly. Her parents divorce and in 1946, Eva’s mother Ruth Hesse commits suicide after learning that her parents had died in the camps. Eva Hesse takes up painting, studying under Josef Albers, later meeting minimalist Sol Lewitt, who becomes an important influence and friend. In 1961, Hesse marries sculptor Tom Doyle and in 1964 undertakes a residency in an abandoned textile factory in Germany. It is here she begins to develop more sculptural works. Back in New York, Hesse separates from Doyle, and frequents the hardware stores on Canal Street to purchase her unorthodox materials – rubber casings, latex, plastics, fibreglass and resin. In 1969, she collapses and is diagnosed with a brain tumour. She is operated on twice and undergoes radiation and chemotherapy treatments. Hesse continues to work through her illness, but in March 1970 she re-enters hospital for a third operation, from which she does not recover.

The artist’s early death and the trauma of her background have led some cultural commentators to warn against pathologizing her work “as wound.” In an interview with Cindy Nemser published posthumously in Artforum in 1970, Hesse admits that life and sickness, are inescapably part of her art: “Art and work and art and life are very connected and my whole life has been absurd. There isn’t a thing in my life that has happened that hasn’t been extreme – personal health, family, economic situation. My art, my school, my personal friends were the best things I ever had. And now back to extreme sickness – all extreme – all absurd.”

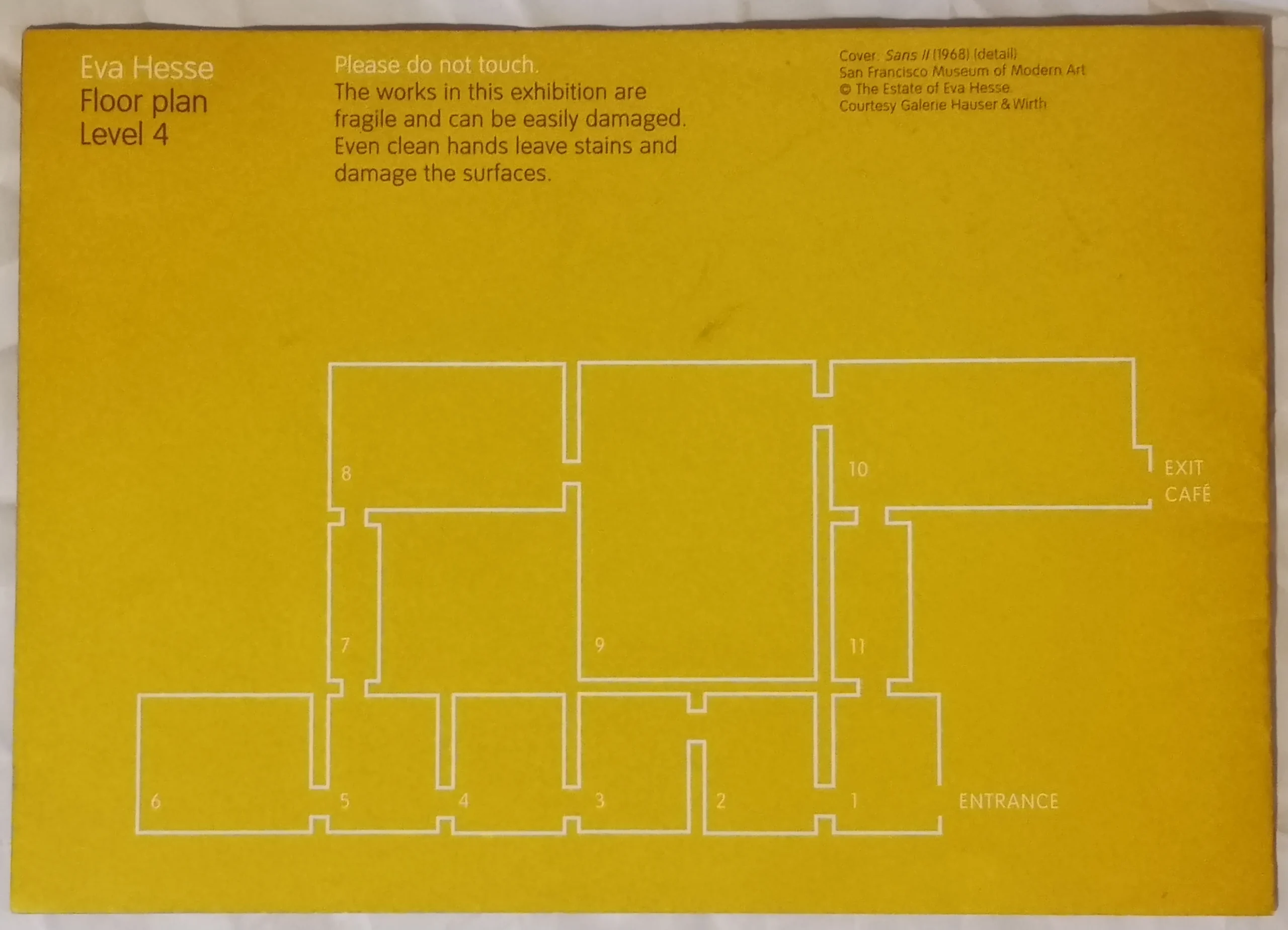

In 2003, I saw an exhibition of Hesse’s work at Tate Modern. At that time, the institution was still very new, but 33 years after her death, visitors were aware of the fragility of Hesse’s sculptures. Their colours had darkened, and the rubber used in some prone to cracking; some pieces teetered on the edge of collapse. Warned of their impermanence, Hesse responded in 1970, “Life doesn’t last; art doesn’t last.” The artist worked organically, playing with different materials, building up layers of resin as if to create a skin. There has been speculation that some of the mediums she worked with were toxic – wire with asbestos lining sold on Canal Street; the poisonous fumes given off by others, although it’s difficult to say whether these contributed to her illness.

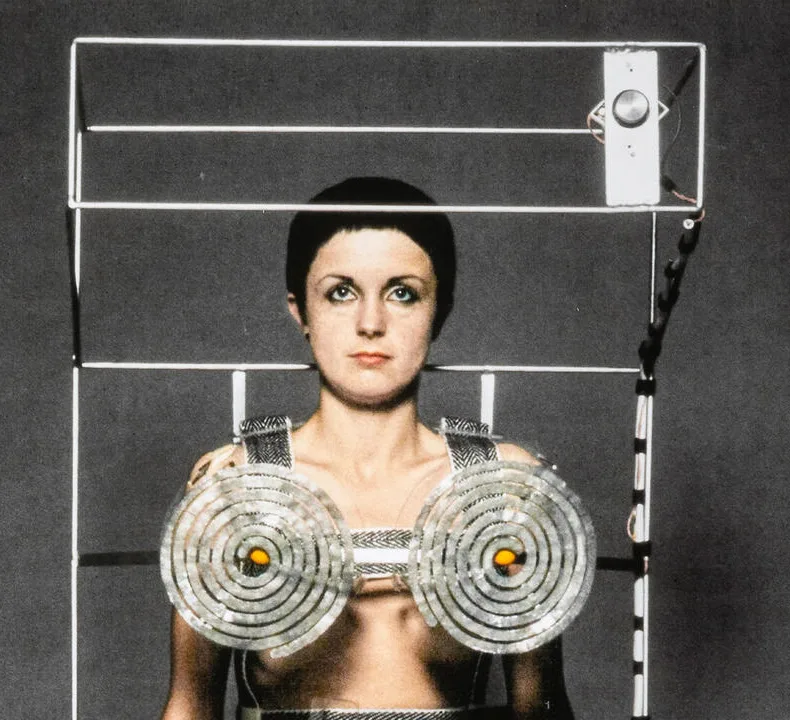

British artist Helen Chadwick (1953-1996) was born in Croydon to a Greek mother and English father. She went on to develop a multimedia practice that included photography and sculpture and explored ideas around desire and disgust in association with the human body. Chadwick shares the same spirit of playfulness and experimentation as Hesse and the same challenges of working in a man’s world (not much had changed for female artists between 1970 and 1996). Chadwick’s approach to making was more planned and conceptual than Hesse, and she enjoyed a greater degree of success, having been the first woman to be nominated for the Turner Prize in 1987. She, too, worked with unorthodox materials. For Carcass, a two-metre-tall glass column displayed as one half of an installation at the ICA in 1986, Chadwick collected nine months’ worth of domestic compost from her home and the houses of her neighbours on Beck Road in Hackney. There is footage of her emptying these into the glass column with ungloved hands – a striking detail when viewed from a post-Covid age.

Chadwick described Carcass as a “tower of corruption and decay”, a stack of detritus and death that she paired with a second piece, The Oval Court. This work, now permanently housed in the V&A, presented twelve cyanotype-blue photocopies of the artist’s naked body on the floor, adrift in a pool alongside photocopies of dead animals and fruits, with five golden spheres on the surface, the colour combinations recalling the luxury pigments of Byzantine paintings, lapis lazuli blue and gold leaf. The fermentation of the vegetal matter of Carcass within its glass tank meant that Chadwick had to feed it compost on a daily basis. “It was constantly percolating bubbles,” she said in an interview in 1986. “So, ironically, it became more a metaphor of life than The Oval Court stretched out like a blue corpse in the next room.”During the course of the exhibition, Carcass began to leak, and when staff tried to move the glass column the structure collapsed, vomiting 10 gallons of rotted food and stench across the gallery floor.

Carcass was not the only work by Chadwick to come undone. In May 2004, a fire swept through a warehouse in East London that stored artworks by major British artists, reducing them to ash. Among them were ten pieces by Chadwick, including Cyclops Cameo (1995). The artist’s early death at the age of 42, her preoccupations with the body as a vehicle for thought as well as sensation, and themes of life, birth and memento mori make such losses poignant, bringing the physical fragility of both artist and artwork into a mortal pairing. Except that while Chadwick explored the notion of binaries, she also questioned them, lending the pieces contemporary resonance.

In the late 1980s, Chadwick moved away from using photographs of her naked self (with face averted) towards pieces that explored the functioning and fabric of an ungendered body, from cells to flesh to bodily fluids. In 2004, I saw Cacao at the Barbican and remember the bubbling smell of this giant chocolate fountain with its penile spout and the luxurious unctuousness of all that gloopy chocolate, offset by a title that associated it with runny shit, a push-pull of attraction and repulsion.

Continuing with the body fluids theme, Chadwick’s Piss Flowers (1991-2) are currently on show at Tate Modern. Created during a residency in ice-bound Canada, Chadwick and her collaborator David Notarius urinated into mounds of snow that were cut into 12 flower shapes using a giant cookie cutter implement, the cavities formed by the warm liquid were filled with plaster then cast in bronze and painted in white enamel. For Chadwick, the interest of these sculptures lay in the gender inversion of whose piss created which form; Chadwick’s made long stamen-like projections, while Notarius’ were squat and petal-shaped. The artist described their creation as an erotic act, but it was also the permanent fixing of a private inconsequential bodily function in a substance that normally melts and vanishes, such as snow. The crumbed and cratered surfaces of Piss Flowers made me think of dead planets, where life may once have existed but no more.

Illness cut short the life and career of Chadwick differently to Hesse. Eva Hesse was aware of being ill, of time running out; she listed her medications in her diaries and wrote about her health. Helen Chadwick supported herself by teaching and died suddenly and unexpectedly on a day packed with activity. It is still not certain what killed her: heart attack? Mystery virus? Her last project had been a residency at King’s College Hospital in London where she photographed fertilised human eggs at the Assisted Conception Unit, which had been rejected for implantation in the womb. She arranged them in shapes that recalled Victorian mourning jewellery, while the title of one piece, Monstrance, referred to the Catholic vessel used to carry the consecrated bread during the Eucharist. In a way, these final works transformed into Chadwick’s own memorial.

In 1925, Virginia Woolf wrote her essay On Being Ill lamenting the lack of interest from writers on the subject: “Literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear…. On the contrary, the very opposite is true. All day, all night, the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February…”

In the work of Eva Hesse, the private and the personal become public and absurd. “The artist is there, embedded in what you’re looking at,” observed British artist Phyllida Barlow. Meanwhile, Helen Chadwick challenges the separation of mind and body directly in her Enfleshings series, in which cuts of steak are made into light boxes, bringing the light bulb of thought into the flesh of the body. Thus do these two artists move through its “daily drama”, as Virginia Woolf called it. “The effect of Seven Poles re-orientated me,” writes Donnelly, following her visit to Hesse’s sculpture at the Centre Pompidou. “…and through my evaluation of it, re-shaped the events which had led me to it.” An assertion of the healing power of such encounters with art.

Written by Deborah Nash

- The Courtauld Institute: Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams 20 June to 14 September 2025

- Tate Modern: Artist Rooms: Helen Chadwick until 8 June 2025

- The Hepworth Wakefield: Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures 17 May to 27 October 2025

- Body High: Death, Drugs & Eva Hesse by Ryann Donnelly. Published by Repeater Books

- Ryann Donnelly was in conversation with Amah-Rose Abrams on 19 May at the ICA