Some words of wisdom from the spellbinding artist on the importance of stillness and sitting

down.

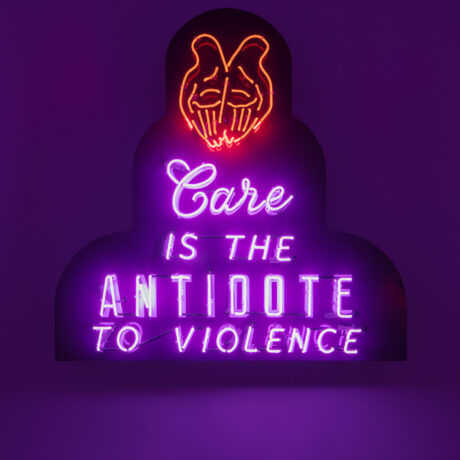

The first time I saw Ja’Tovia Gary’s work was in a packed gallery at the ICA in San Francisco. Last year the museum held an exhibition on the liberation and celebration of Black women through the lens of leisure and physical adornment, curated by Autumn Breon and Tahirah Rasheed. The exhibition featured a heavyweight list of Black artists, but unsurprisingly, the image that was often spotlighted in the marketing campaign, the article reviews, and the piece that made the main feed on Instagram was Ja’Tovia Gary’s Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017), 2020. Within the work, Gary utilises words spoken by writer Saidiya Hartman in which she once said, “Care is the Antidote to Violence.” And while it summed up many of the themes of the exhibition, it also sums up the heart of much of Gary’s work. If we just showed a bit more care towards Black people, what would the world look like?

While Gary has been making work for years, astounding installations and exploratory films, it appears she has exploded all over the scene this past year with openings across the world. Most recently, the third channel to her artistic investigation of Monet’s garden, The Giverny Suite, came on view to art lovers at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, just a few weeks ago. But before Gary had the chance to celebrate her work on one of the art world’s largest stages, she caught COVID. With this, we postponed our own chat for a later date, knowing how long it takes to get back onto your feet when you awaken from COVID’s fog. Once we connected, unsurprisingly, I learned the artist is thoughtful about all of life’s hurdles and found in the haze the urgent lesson that the universe needed her to hear: “Sit down.”

Within the film, there is one pinnacle question that reverberates throughout each scene that is both asked to her subjects and underlies the same conceptual galaxy of care that Gary’s work traverses through: “Do you feel safe?” While our conversation sometimes meandered, it always navigated us back to this notion. There is no safety without care. Care for nature. Care for others. And most importantly, as Gary was reminded, care for ourselves.

Shaquille Heath: This has been quite a year for you in terms of work, revisiting old settings, awards, and all of these amazing things that you’ve been going through. And now we’re about a week out from celebrating the opening of The Giverny Suite at MoMA. So, I first wanted to say congratulations! And second, see how you’re feeling.

Ja’Tovia Gary: Thank you so much! It’s good. It’s a little bittersweet because that was actually when I got COVID. So I missed the opening, unfortunately. It’s great that the work is up, and it will be up for a little under a year. I’m really happy and very excited to be able to have that work in such an esteemed space where there are so many people coming in. So the opportunity to share it with a great deal of people… that’s exciting for me.

Yeah, it was a little sad to miss the opening. However, I’m going back to New York for a gala soon. So there’ll be a moment to have a proper celebration and all of those wonderful things. But it was kind of, I don’t know, not to get super existential– I felt like even though I got sick, it was really important for me to slow down. This is actually my second time having COVID. I had it in 2022, and it forced me to re-engage with how I work and not allow myself to be run ragged. Or even to run myself ragged. So, this felt like a little bit of a reminder. Like, yes, there are all of these amazing things happening. And yes, you’ve done some great work, and you want to see the fruits of your labour. However, when the universe says, “Sit down,” you have a seat. And that’s very much what it felt like. It was also a reminder that the important thing is to share this work. To get this artwork out and to continue the conversation. It’s not about the champagne opening, right? It’s not about everybody clapping for you and whatever you post on the gram. Those are fun. Those are nice little moments. But the reality of the situation is you’re here to make this very important work and to share it with as many people as possible. So that was my takeaway from that. To kind of remember to keep your eyes on the prize here. And not be swayed by the trappings of the things. So, I tried to take something positive from it.

However, when the universe says “sits down,” you have a seat.

Well, at the same time, though, I feel like your work deals so much with the fact–specifically around black women–being overworked and underappreciated. And so, in one way, it showcases your own susceptibility to those same ventures. But on the other hand, I feel like, particularly as Black women, it is always important to take the moment for your flowers. So I feel a bit sad that you weren’t able to have that.

Yeah, I’m not sad. And I’ll tell you why–because there’ve been so many moments of applause this year. It almost feels overwhelming, a little bit. So it kind of felt like I needed this moment to take stock of what’s really going on, right? And what’s really important. The flowers are there all the time. The flowers will be there. The huge gala. So I’m just really trying to kind of be settled around what has happened. A lot of people have said that, “Oh, that’s so sad!” And I’m like, “I’m telling you, it’s not!” Haha. “I’m telling you, it was for the best!” In some ways, it felt very heartbreaking. But in the moment, I was like, oh, I need to lay down.

Haha! COVID will do that. That feeling like, I need to be horizontal.

Yeah. I think that was the kind of takeaway. That even if it is a ton of work that you’re dreading, or even if the flowers are about to come, when you have to lay down, you have to lay down, or else you will be sat down. It reminds me of Maya Angelou. Somebody was talking about “the bad press” and “the good press” and the flowers versus the criticism, the accolades versus whatever. And she was like, “I don’t pick it up, and I don’t put it down.” Meaning if it’s good, I don’t pick it up. I don’t put it down. If it’s bad, I don’t pick it up. I don’t put it down. And it’s hard to do that when it’s good. Right. It’s hard to do that when everyone’s clapping. But I think it’s a really good practice to get into, you feel me. I’m trying to get into it. I’m a Leo, I love my flowers! But at the same time…

That’s often not the every day.

It can’t be! It can’t be! It can’t be the thing that you’re driving towards. It can’t be. And so these are reminders. And they’re welcome reminders. Yeah, it was a little upsetting, but listen, MOMA wasn’t the only thing I missed. I had screenings. I have work that’s in festivals right now, as well. So, I had an international premiere at TIFF, Toronto International Film Festival. I was supposed to go to London, where you are. But again, I needed to lay down.

When the universe speaks, the universe speaks. So…do you listen? And when you’re laying horizontal because you must, are you allowing yourself to actually relax? I know that you’re a big reader, so do you allow yourself to read for fun? Or do you find that your mind is still bubbling with things now that you have silence?

I think it vacillates. There are definitely moments where I’m thinking about the next thing. It’s really hard to tap out of that. If you’re someone who is interested in creating things and interested in sharing… I don’t want to call it ambition. Because it’s a little bit more than ambition, it feels a little bit like, you know, a responsibility. You’ve been given these things, and your job is to share them. Mama KoKo is an elder in my community, and in my latest film, she says, “We’re on an errand for the spirits.” So those things, of course, are still spinning in my mind. I must do this. I need to make sure I’m well so that I can continue to do this. But also, yes, I enjoyed my free time. That’s also why I wasn’t so sad. Because I’m like, “Oh, I actually need this! I need to lay down!” I want to read. I want to empty my mind. I need to relax. I need to sleep. So yes, I definitely enjoyed having that break. And it almost feels bad to say that, right? Because there were responsibilities. But you know, I got a doctor’s note.

One of the things that I was wondering about, and maybe this question is a bit different because you weren’t there in person. But, I imagine something like The Giverny Suite where you’re in the garden, and you’re working in this very solitary nature–to go from that to inside in the gallery space. How is the experience when you see your work also make that transition? And what are those feelings that come up when you’re seeing that work reflected in the eyes of your visitors?

Yeah, it’s really overwhelming. To me, that is the pinnacle of the work. That is when the work is complete. When we’re able to share it, and people are experiencing it. Seeing their responses, hearing their responses. I’ve exhibited this particular work six times. And it’s usually a really nice sized gallery, because the screens are at least 15 feet tall, there’s three of them. And to have people come in and be immersed by the sounds, by the images, and then by the atmosphere that we are creating together… It is unparalleled. To me, that is when the work is complete. It’s not completed when I have finished editing. Or I have made a file to be exported. Or when we have set up the final pieces of the installation. When the people enter the space, and they are moved and transformed by what they’re seeing, that is the culmination of our experience. Once we can make this thing together, right? Once we can now have this kind of dialogue. So for me, it’s always really exciting.

I’m reminded of the magic of being a child artist. Even as a young person, I was an artist. I was in theatre, and I would draw and I would write stories. Having something that starts from an idea and then rendering it into a physical manifestation that you can see, touch, and experience. There’s magic in that. Right? And to have that experience at this level, as an adult with however many people, I’m reminded of that magic.

Do your feelings about the work change when you see it in the gallery? I’m sure when you’re creating the work, you’re not working on a 15-foot screen, right? So when you finally get it into the gallery and you see it on the big screens, do you feel complete? Or is there a part of you that’s like, oh, I need to go back and change this?

It really depends on the work. This vacillates. Sometimes, you engage in work that is early, like college-era work. I look back on things from 2015, and sometimes I’m like, oof, if I were doing this over, I would change this. I would go about it this way. But at the end of the day, you have to release that because it’s all a part of the trajectory. It’s all a part of your process and your journey as an artist, and we can’t go back and change it. I mean, you could, but then what would be the point, right? It’s like, that’s where I was at that time. I look at a lot of the work as these psychological thumbprints or timestamps. This is where I was mentally, emotionally, physically, and psychologically at that point in time. It’s like an heirloom of my reality as an artist and as a human being, in fact. So I don’t ever feel the urge to kind of rewrite the work.

I’m reminded of the magic of being a child artist. Even as a young person, I was an artist. I was in theater, and I would draw, and I would write stories. Having something that starts from an idea, and then rendering it into a physical manifestation that you can see, touch, experience. There’s magic in that.

Actually… actually, I have to say… because The Giverny Suite is a three-channel piece. But there is The Giverny Document, which is the single channel, and it’s a part of the suite. It’s actually the middle channel of the three channels, so it can exist alone. And then inside of that is Giverny I (Négresse Impériale), which is a six-minute moment, and it’s that garden moment that’s kind of woven throughout the 40 minutes. So technically, you have a number of films that are within a film, almost like a Russian doll, you know, you open, and there’s another one. And in many respects, the process of making that film is kind of not exactly what this question is getting at, but it is… this notion of continuing the conversation, right? I didn’t look at the first film, which was Giverny I (Négresse Impériale) and say, I hate this, or I don’t like this. I looked at it and said, there’s more to the conversation, right? And I made the 40-minute piece. And then, I added two channels because there was just so much more left to say.

And the garden is this place that you keep coming back to. Can you talk to me about what you felt there and why it lingers with you?

That’s a good question. It was tough. I’m not going to lie. It was actually my first artist residency. I got it in 2016. I had never had one before. And you know, on paper, it’s a really good one. It’s about two months in Northern France on this really beautiful estate, where Monet’s garden and home are. We were staying in mansions. There were about four other artists and six Ph.D. art history scholars. And the grounds were beautiful, bucolic. But you know, I was the only Black person there. So that brings about a number of all sorts of complications and possible areas of grief. I felt like I was hypervisible or completely invisible. I also felt the kind of pervasive weight of violence that was underlying the space because it was the summer of 2016. This was the summer when Philando Castile and Alton Sterling were murdered by the police. This was also the summer when the Pulse Nightclub shooting happened, and about 50 queer people were killed at a nightclub in Florida. There was also this ongoing migrant crisis. Boats were capsizing in the Mediterranean, and dozens of people were dying. So, I would hear this on the news and social media. All while surrounded by the beauty of this man-made space. And wrestling with the legacy of U.S. and French imperialism, as well as the French masters of impressionism like Claude Monet. So, thinking through art history and its place within this kind of cultural hegemony.

So, there was a lot going on psychologically, and I was having a difficult time. But I was also enjoying myself. So there was this dissonance. Also, I was removed from my systems of care. My friends were not there, and my family was not there. And then there were moments where I was aggressed by French men in the space. So, I began to think very seriously about my safety. I began to compare it to my reality of living in Brooklyn at the time. I lived in Brooklyn for 16 years. So this idea of street harassment or this idea of feeling unsafe in what is supposed to be a democratic, free and open space emerged. So, there was a lot happening emotionally for me there. And I attempted to address it by placing myself in that space. You know, I was kind of depressed for the first month. But I would pluck the leaves from the garden, and I would make these strips of beautiful petals on film. And so that’s what you’re seeing flickering in the film. And then I placed myself in the garden–they allowed me to do that once everyone was gone. And so I just said to myself, Listen, you’re not going to be here forever, figure it out. You have to do something while you’re here. Even though it’s disturbing, it’s kind of a once-in-a-lifetime moment. Let’s make sure we’re generating something so that we can transmute this experience into something worthwhile and beautiful.

I’m very moved by that. Because I was wondering how you came to the question, “Do you feel safe?” The question that you’re asking all of the women in the film. I mean, that’s heavy shit. Not only are you thinking through these questions yourself, you’re thinking about what this means for your own body. You’re thinking about what this means for all Black bodies. You’re asking this question of women, and you’re taking on their responses in whatever form that may be. How do you take care of yourself after that heaviness? What is your release because you can’t carry that forever?

Yeah, I have a spiritual practice. I practise a traditional African spiritual religion. I come from Pentecostal preachers. I’m a daughter of the South–a bunch of Pentecostal evangelicals, but I have returned to an indigenous West African spiritual system. It requires me to be in prayer and meditation daily, or else I will literally spiral out. It’s something that I put at the forefront of my life. That’s also why, in the installation, you see these two altars for these two orisha. One is to Yemaya, and one is to Oshun. Yemaya is the mother orisha, and her domain is the ocean. And she is said to have as many children as there are fish in the sea. She protects women, and she protects children. She’s rich, she’s fertile. She’s fecund. She’s overflowing with all the goodness of what it means to be a woman, as is Oshun. Oshun is very beautiful and very rich. Her domain is the freshwater, so the streams, the lakes, the rivers. She is said to be the orisha that makes life worth living. She is sweet. All of the goodness associated with being a woman you will find in Oshun. So, it was important for me to centre these two entities because of their power. They are protectors. And you can’t do anything without them. There are a number of other orisha that appear as men or masculine figures. But these two women figures, these two female figures, are, in fact, my heads, right? They protect my head. And so, it was important for me to acknowledge them in this space because they are helpful in making sure that I am protected and that I do not carry the weight of the world. Or the violence of the past on me. If you’re a practitioner, you understand that you have to make space for them in your life. They are not simply these abstractions, you know. A lot of the spiritual traditions that are from West Africa are earth-based, meaning orisha is here on the earth. You can point to them as manifestations of the earth in the land, whether it be the ocean, a mountain, or a volcano. And so to make space for them in the exhibition was incredibly important to me. We have to give honour. We have to give space and acknowledgement.

It feels that they’re not only giving protection for you, but they’re giving protection for your visitors who are in that space and who will be dealing with the same kind of feelings and thoughts as you’re presenting to them.

That’s such a great point. Because the work, as you said, can be very heavy. It does elicit a number of feelings for people. And we do withhold the dead and dying Black body, but you can hear that there is violence happening. And so, for many people, it still triggers them. Whether we are reproducing that image or not, you are inciting a kind of emotional response. And so we also want to attend to that response. That’s why Nina [Simone] is there. There are moments where you’re just looking at water, right? There are moments where you’re kind of being rocked by the sound of a soothing voice. And so all of that, including the altars, is adding to this atmosphere. Where you’re going to run through the full gamut of human emotions, and you’re going to be caught at the end. You’re going to be nestled in like in a mother’s bosom.

Written by Shaquille Heath

The Giverny Suite is now on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

FIND OUT MORE