The strange thing about the Barbican’s Modern Couples exhibition is that sure, there are a hell of a lot of couples, but there is not really enough art. Maybe the idea is that we focus on modernity and coupledom, instead. Maybe the show’s just too ambitious. But in covering it, I thought it might be useful to really think about the “modern love” part, and all that entails: why did these couples work, or not? Why were so many of them so clearly problematic? In lieu of a dating expert, I consulted the next best thing—a woman who knows a thing or two about heartbreak (hers, mine, any number of the people who seem to corner her on trains and spill their life stories): my mum, whose actual name is Elaine Coombes.

Previous gallery trips with her have been both hilarious and surreal (the Paul Klee exhibition saw her decide that a number of the portraits were the spit of Jimmy Somerville from Bronski Beat

); but it turns out that on the subject of the injustices and power imbalances that seemed to define so many relationships on show at the Barbican, she had more than a few wise words.

- Left: Camille Claudel, Portrait of Rodin, 1888-1889. Courtesy of Musée Rodin, Paris. Right: Auguste Rodin, Mask of Camille Claudel, 1889. Courtesy of Musée Rodin, Paris

The exhibition opens with Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin, a partnership emblematic of the cruelties of being a young “muse” and lover to a sort of sculptor elder statesman. The show seems to gloss over just how much impact Claudel had on Rodin’s work as his assistant, working on tricky jobs such as hands and feet for major pieces including The Gates of Hell. The show also breezily skims past the fact Rodin’s relationship with Claudel was concurrent with his two-decade partnership with Rose Beuret Mignon.

Claudel could not truly be herself as an artist, nor be in a relationship with Rodin, and was unable to get funding for her own, frequently sexually suffused work, and so depended on the older artist financially or was forced to let him take the credit for much of her work. “I imagine that sort of thing’s still happening now,” laments Mum. “Like the saying goes, behind every successful man there’s a good woman. Why do we do it? I don’t know why we do it, ’coz we’re just so nice.”

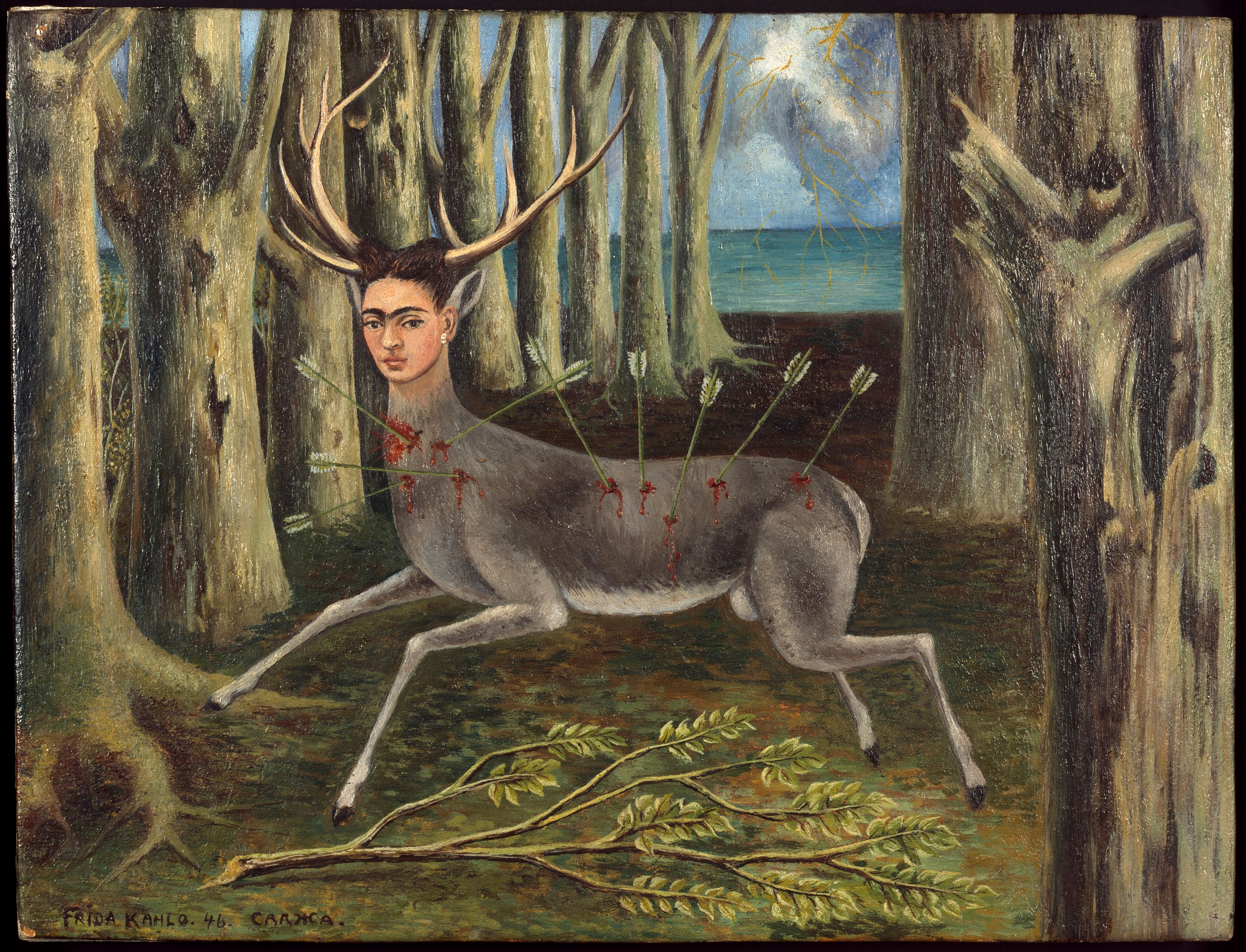

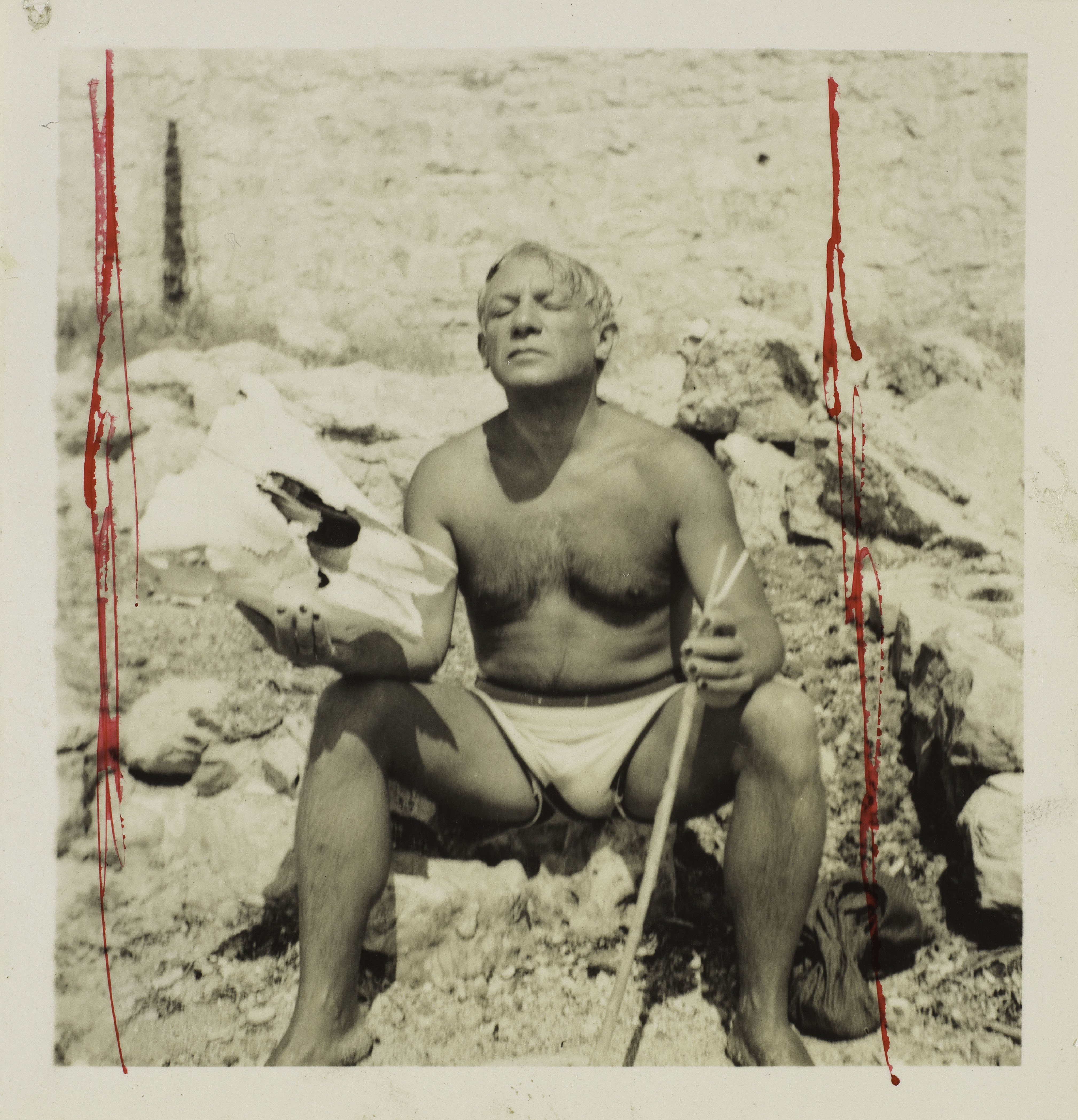

That opener also sets the tone for a number of the relationships detailed in the exhibition in which there was a considerable age gap: interestingly, though, this only seems to be commented on when the woman was older than the man. The text makes a song and dance about the fact that Gustav Mahler was “seven years […] junior” to Alma; though the twenty-six year difference between Picasso and Dora Maar, or Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s twenty-one year gap passes without comment, as does the fact that Lee Miller was seventeen years younger than Man Ray.

“There’s still more judgement about men being with older women,” Mum points out. “We still haven’t changed our views on that—we’re still in a male dominated society. You still have an old fat ugly man chasing after a young girl and it most probably still boils down to position, affluence… It seems like only wealthy women have younger men, look at Joan Collins! But it’s laughed at a lot of the time.”

Running alongside the age-gap conversation is something that becomes apparent regarding the way women in the era were viewed in relation to their “madness”. Many of the women featured appear to end up institutionalized. Take Leonora Carrington, who met Max Ernst when she was nineteen, and he was forty-six (“it was love at first sight”, according to the Barbican). When Ernst was arrested, Carrington had a breakdown in Spain, before running away from her nurses and family to Mexico. In the meantime, Ernst had married Peggy Guggenheim in New York.

Where women’s “madness” was often pathologized, it seemed, men’s “eccentricities” were deemed all part and parcel of creative genius. Mum ponders that the idea of “madness” in women could have been a product of a stifling era in which men—and societal expectations—constrained them. “They couldn’t be themselves,” she says. “Women were labelled mad maybe just because they were trying to assert themselves and be who they actually are, and not just what they’re deemed socially acceptable to be.”

According to the Barbican, the relationships on show were, “at their most productive… inspirational, enabling and empowering”. The difference between “muse” and “collaborator” is plain from the couples on display, but rarely articulated. “A muse sounds almost like a young pretty plaything, doesn’t it?” says Mum. “They like to draw you and do whatever, but you can quite easily be disregarded for the next one to come along. You don’t hear of men being muses really do you? Lust and obsession are very different to love.” It’s hard to see the parity in the relationship between Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso, for instance, aside from the fact they photographed one another, and he created numerous paintings of her “many of which she was profoundly ambivalent about”, according to the Barbican. Throughout their affair Picasso remained in a relationship with his daughter’s mother, Marie-Thérèse Walter; and he left Maar in 1943 for the younger painter Françoise Gilot.

Of course, age gaps and groaning about the mutability of “muses” isn’t to deny that this exhibition is suffused with real, passionate love; and love and lust that built formidable artistic collaborations. One of the most dynamic articulations of this is to be found in Hamburg-based couple Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt’s work (or so it seemed). The pair worked together on electrifying, frequently grotesque and rather terrifying costume and mask designs, creating them from cheap materials such as papier mâché, fabric and cardboard and wearing them for performances dubbed Die Maskentänzer (the mask dancers). The body of scenic art they created was wrought from an entirely holistic process; and the couple were united not just in their output, but in the belief behind it that they wanted to reject modern technology. As such, they made political and economic decisions that went against the grain of many of their peers at the Bauhaus. However, as with any couple, being hard-up can bring friction, especially for a relationship already leaning towards the discordant side of things. In 1924 Schulz killed Holdt as he slept, then killed herself.

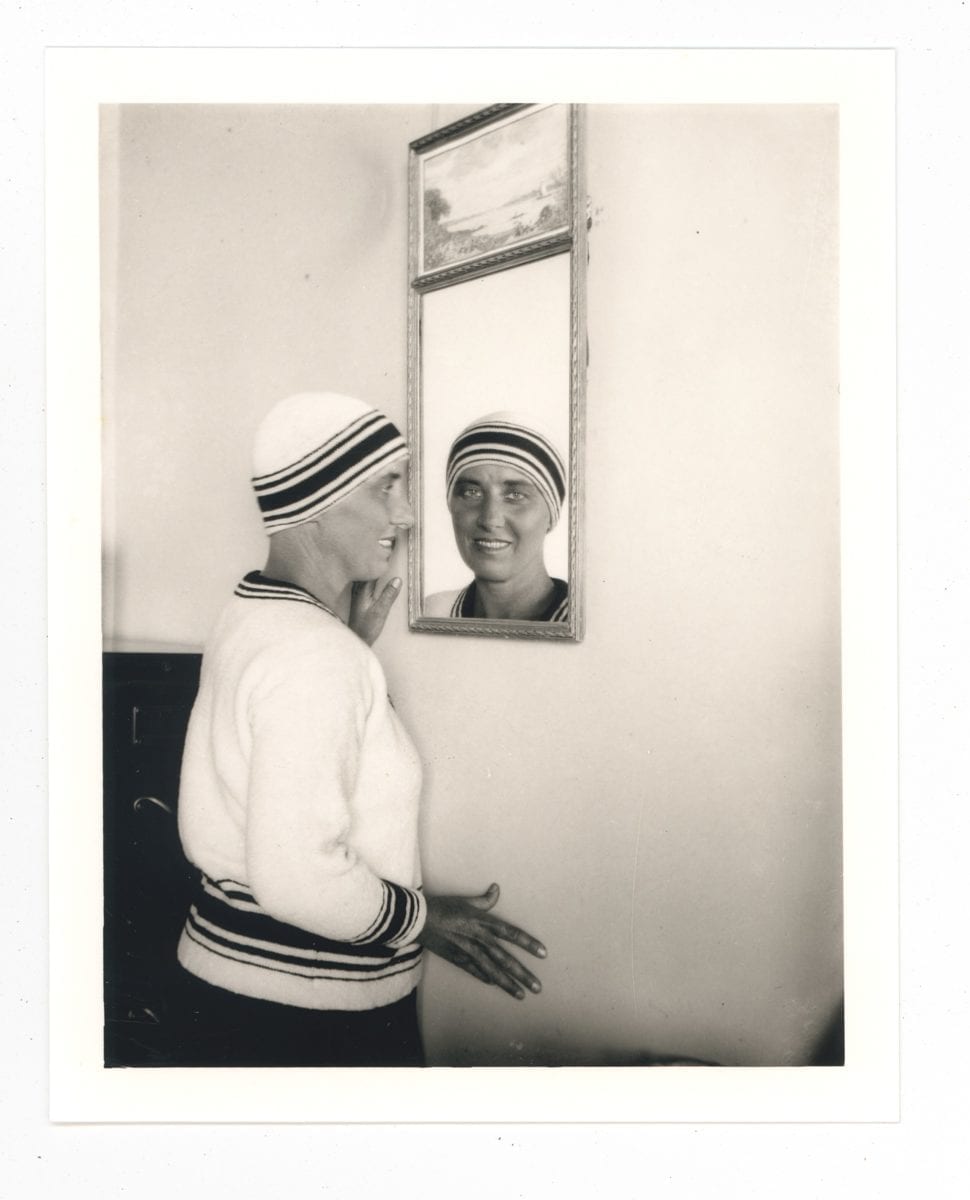

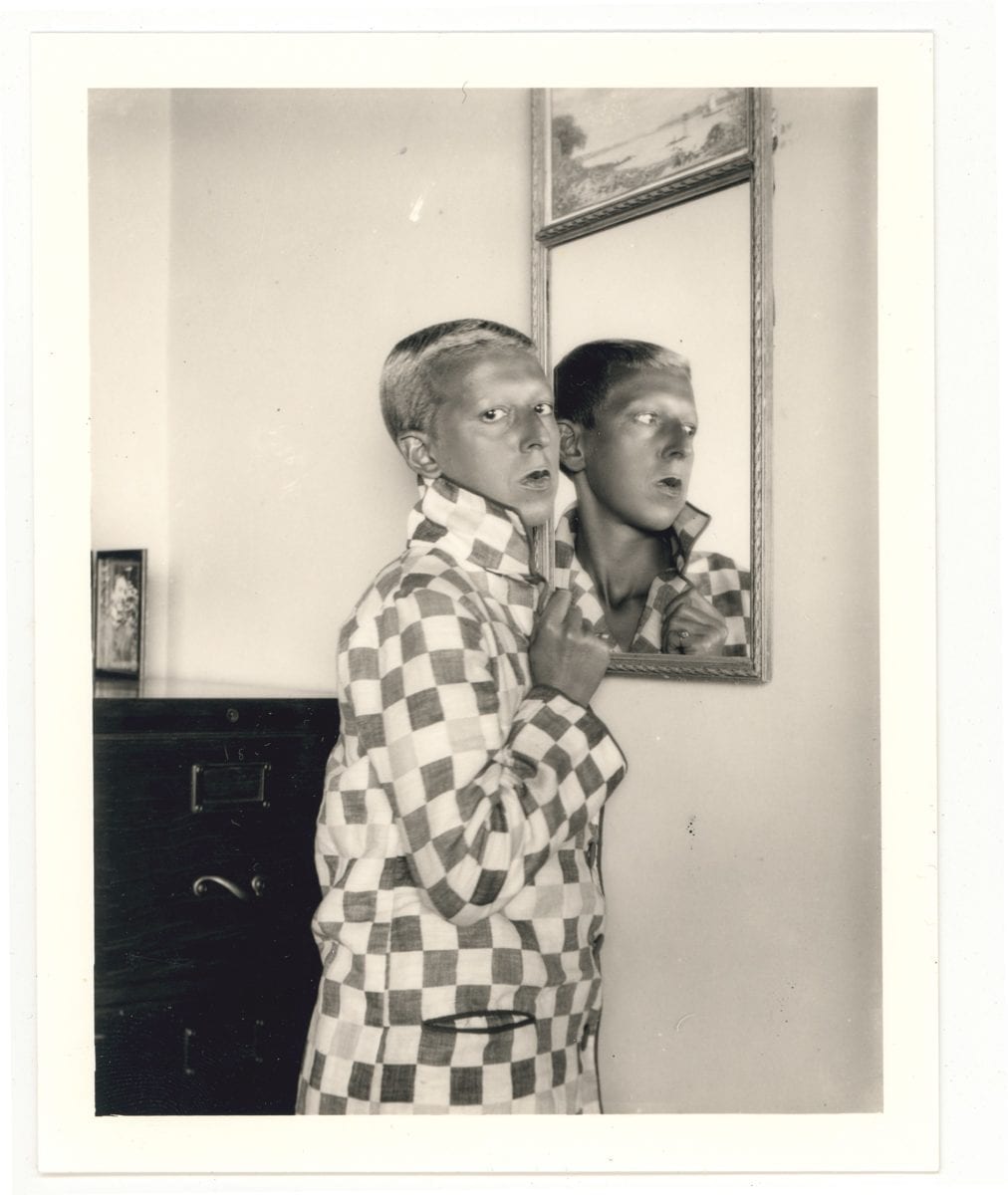

- Left: Claude Cahun, Suzanne Malherbe/Marcel Moore,1928. Right: Claude Cahun, Self-Portrait (Reflected Image in Mirror, Checked Jacket), 1928. Courtesy of Jersey Heritage Collections

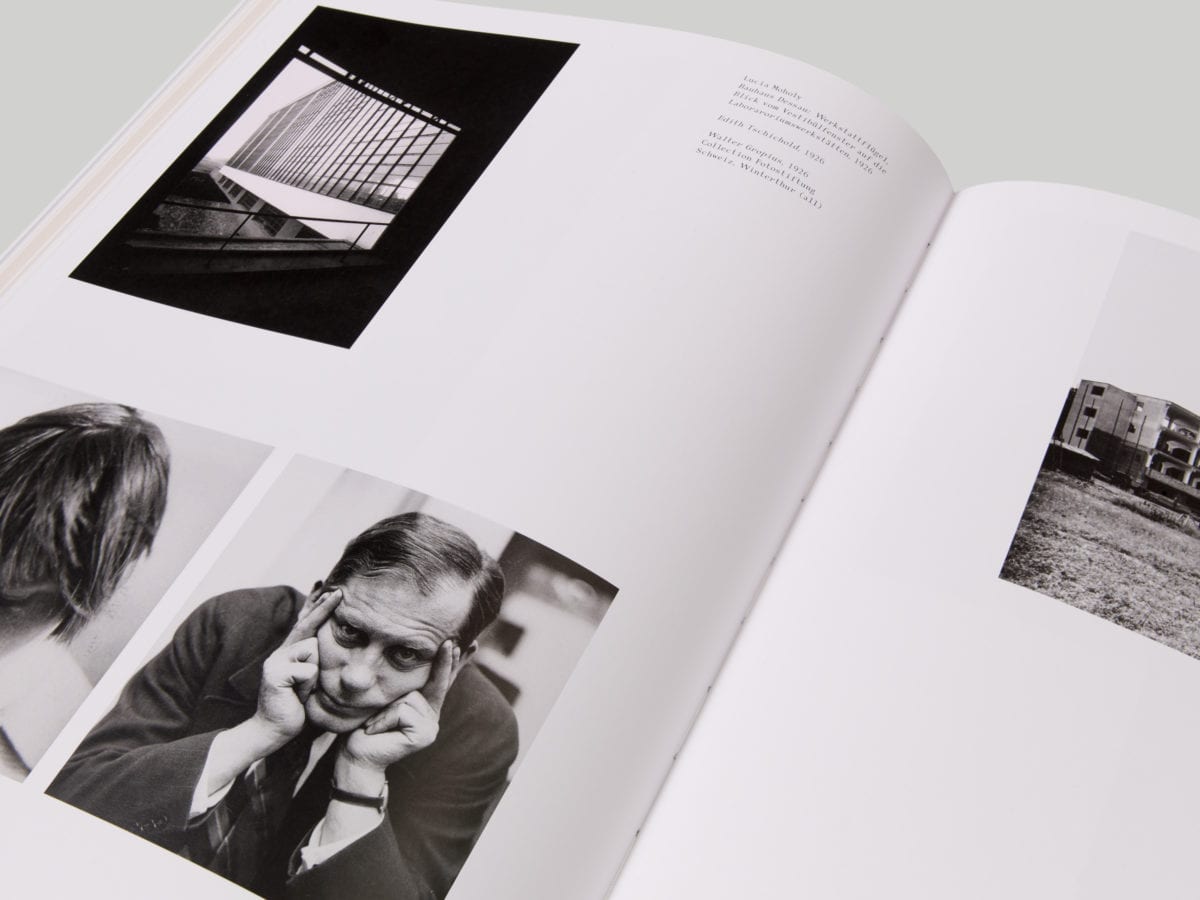

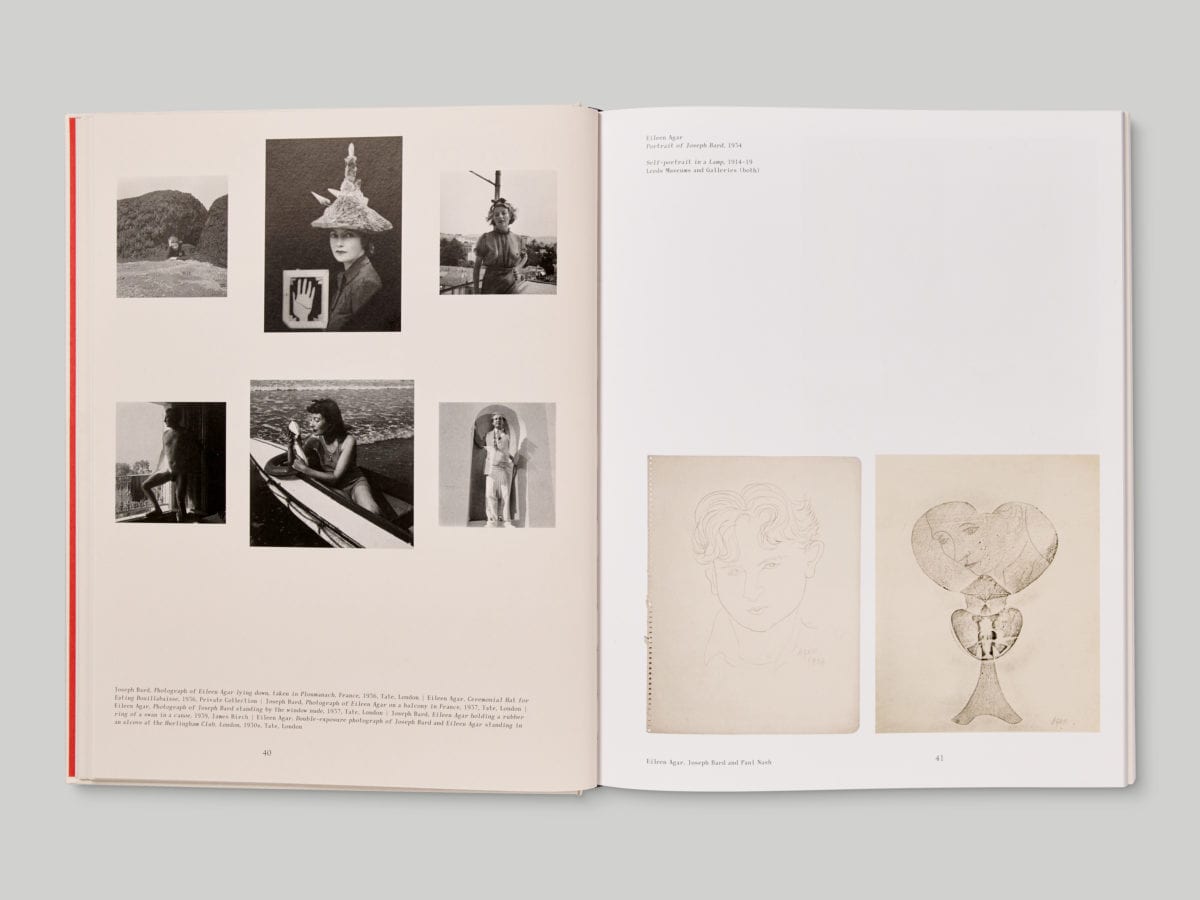

The couple’s work stands out in an exhibition that’s largely text-based: we see handwritten letters, a hell of a lot of wall text, quotes and personal documents, though not nearly as much actual artwork as we’d want. There’s just too much here: the material feels far better suited to a book (and looks brilliant as one, thanks to the publication created for the show, designed by Apfel, whose exhibition graphics are just as subtly beautiful and thoughtful). “We could have just Googled it all really,” says Mum.

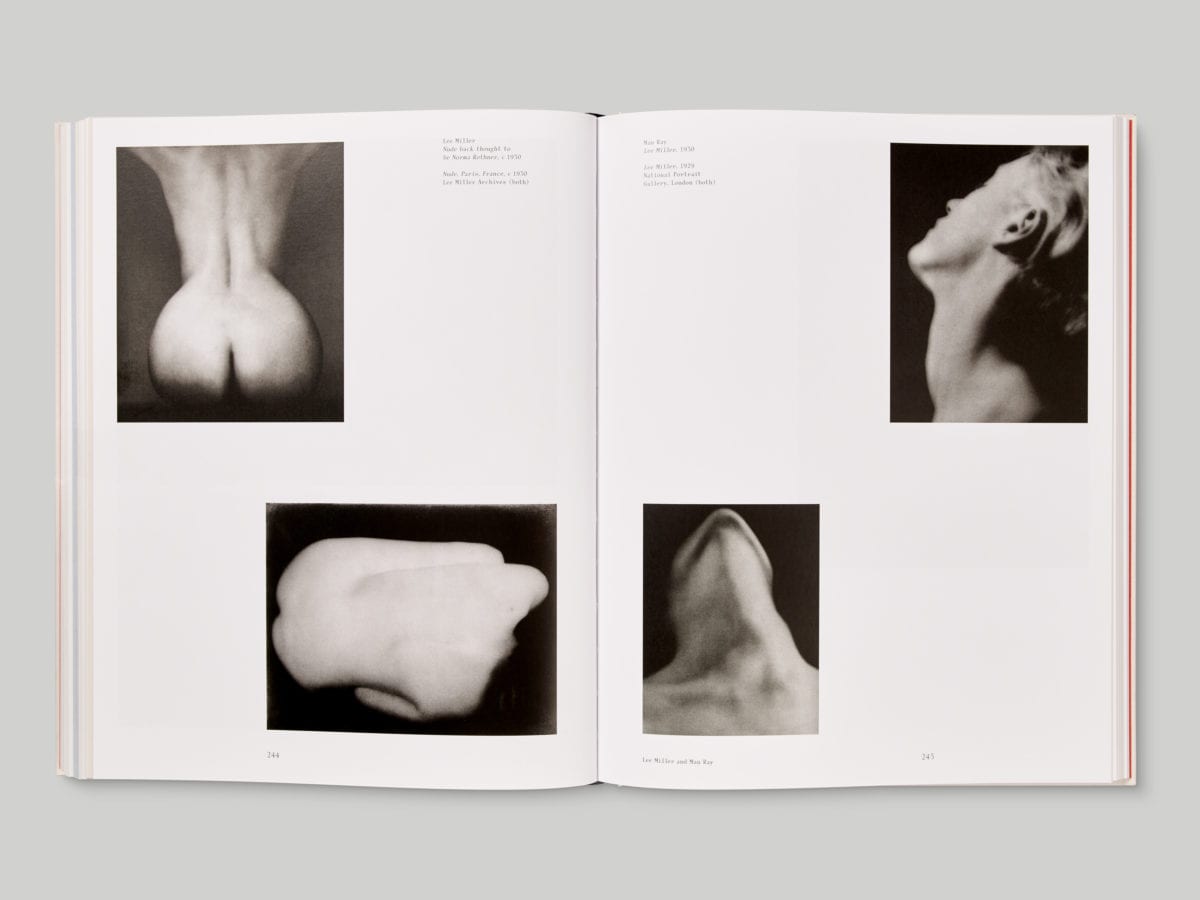

Naturally, much of the show is subtly or explicitly erotic (much has been made of the S&M-infused images of Man Ray and Lee Miller, for instance). So to end, I want to ask the big question. Do artists have better sex? “No!” laughs Mum. “It shouldn’t make any difference whatsoever. They may be very good at telling it, or painting it, but they might be fibbing. Or they might think they’re great at it, but they’re not really.”