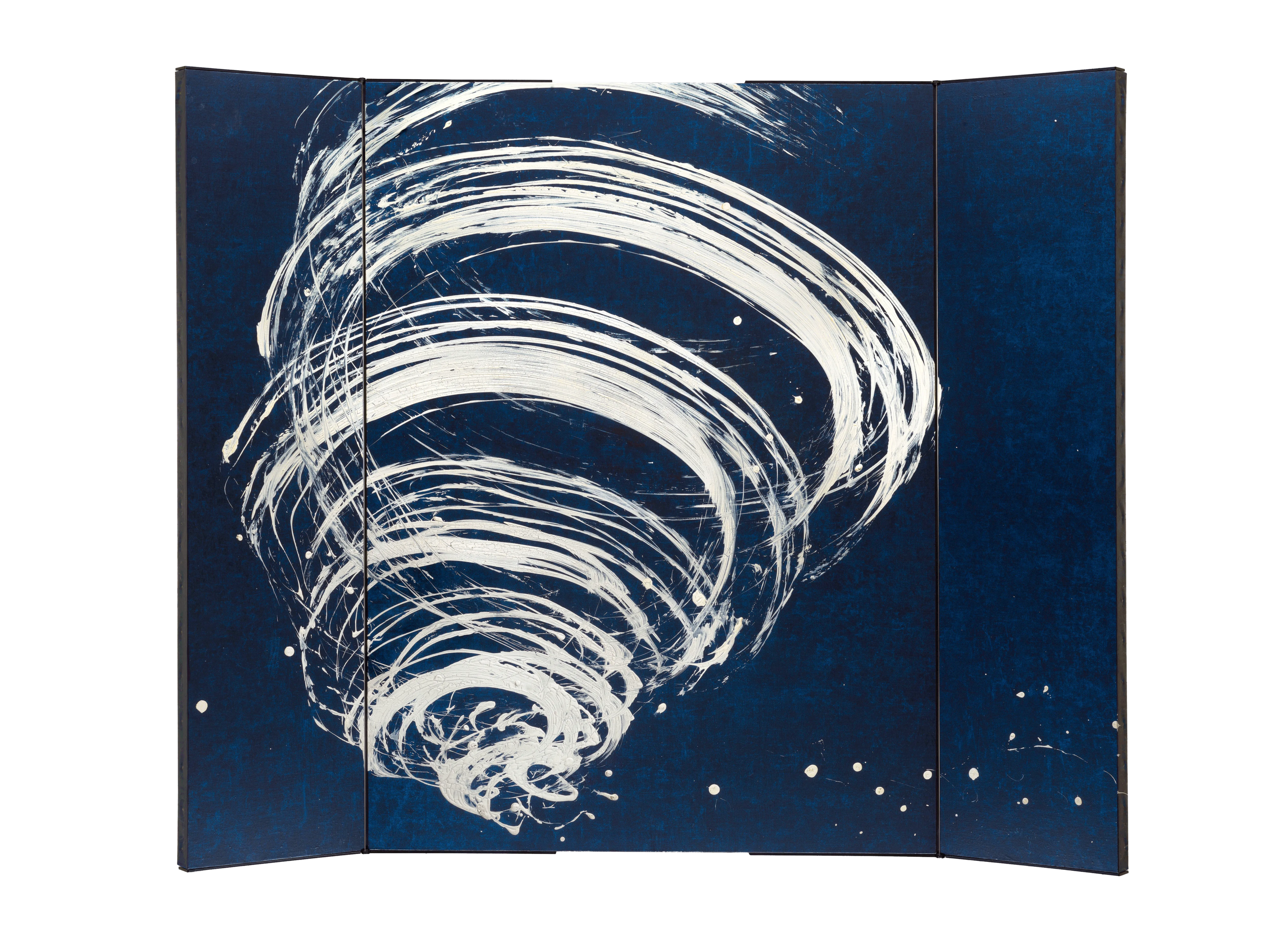

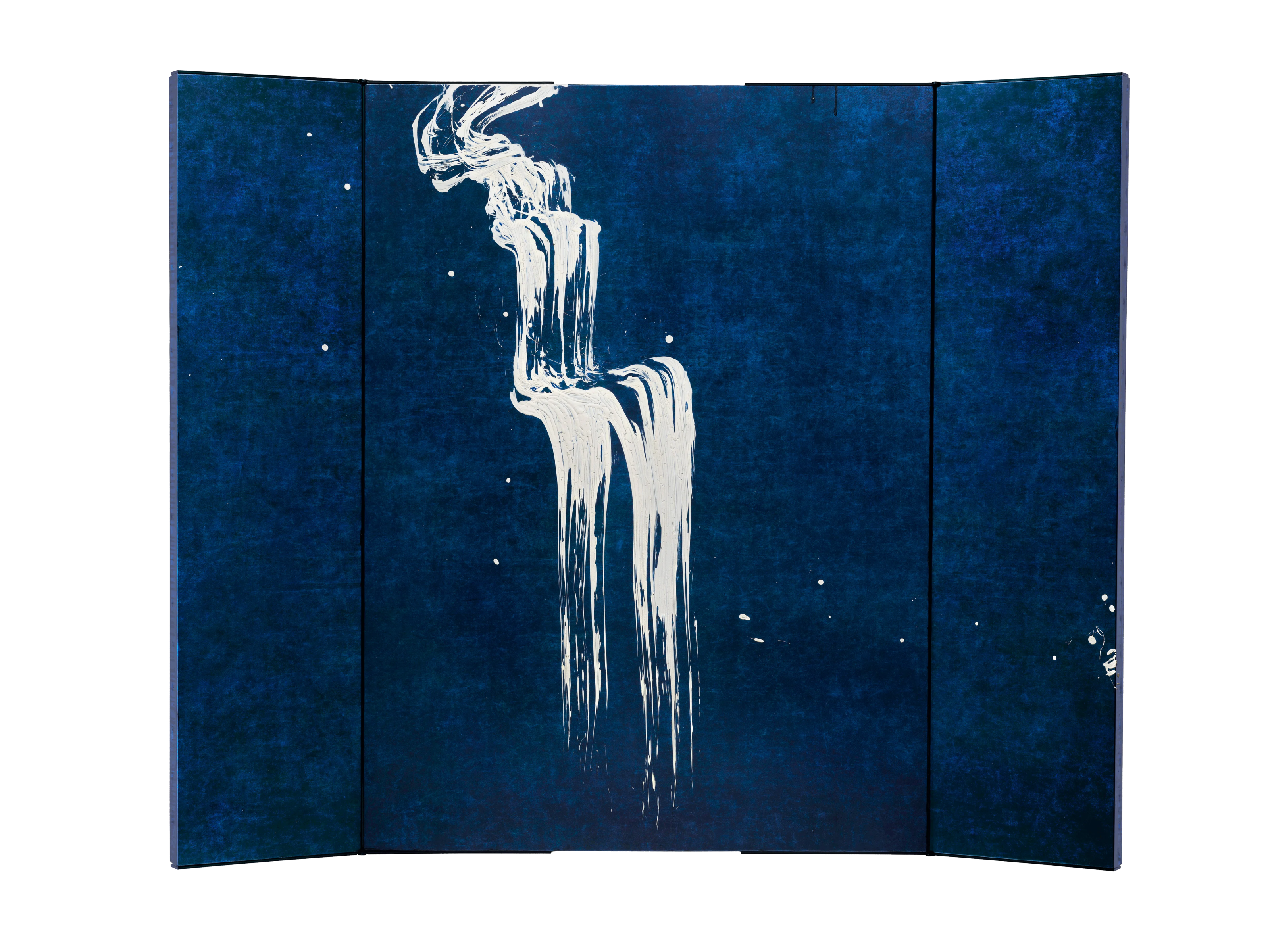

In this installment of ‘Brainwave’, Sofia Hallström sits down with French artist Fabienne Verdier in her studio just outside Paris. Verdier’s practice, rooted in her deep understanding of nature’s rhythms and the energy of brushwork, blends centuries-old traditions of Chinese calligraphy with Western abstraction. In the following conversation, Verdier discusses how her large-scale, horsehair brushes attached to bicycle handles allow her to explore the forces of gravity, wind, and sound on her expansive canvases. Surrounded by the visual evidence of her many influences, from aerial images of rivers to Renaissance altarpieces, Verdier offers insight into how she transforms intangible, invisible forces into physical and sensory experiences through her painting. The conversation spans her engagement with the void, the energy of her brushwork, and her ongoing dialogue with art history, navigating the complex relationships between nature, abstraction, and the body in motion.

Sofia Hallström: In Retables you reimagine the traditional altarpiece structure. How does this historical format impact the way you approach abstraction and the depiction of natural phenomena like gravity, wind, and sound? What are the specific challenges and opportunities that arise from working with this religiously charged form in a non-liturgical context?

Fabienne Verdier: I’ve been lucky enough to have spent a lot of time looking at altarpieces from Flemish, Italian and German painting of the 14th and 15th centuries, from Hans Memling to Van Eyck, from Piero della Francesca to Fra Filippo Lippi or Leonardo da Vinci, from Matthias Grünewald to Martin Schongauer, and I am captivated every time by the physical presence of these works. The multi-panel layout invites a very radical perception of time and space. If those painters were obliged to depict liturgical subjects to evoke the mysteries of life, I thought it would be interesting to adapt this almost cinematographic construction toward an essential issue of today, which is the natural world, its exceptional beauty, and the ways in which we have endangered it; in a way, I was working toward inventing the altarpiece of our time.

SH: Your work often captures invisible forces, transforming abstract ideas into visual forms. Could you describe your process for translating these intangible elements into physical motifs? How do these motifs evolve in your series and across your body of work?

FV: To look at and observe nature is to realize that everything around us is in perpetual motion, that nothing is fixed: everything moves, everything changes. This constant evolution is the key principle of life, and the painter’s challenge, in my opinion, is to convey this movement of all things. That’s why, when I look at a cloud, a river, a skyline, a mountain range, a bud, a reflection on the sea, I try to capture its intrinsic movement on canvas, so that the viewer can also physically feel this sense of impermanence, this thought in motion.

SH: Motifs from your earlier works resurface in the Retables series. Can you talk about the significance of this recurrence, and how your understanding of these themes has deepened or shifted over time? What new perspectives have these recurring motifs brought to your current practice?

FV: In this series, I’m interested in how a dynamic form moves across the altarpiece, from one side to the other. I’m very interested in the cinematic notion of the “off-screen”: in what happens or can be imagined beyond the image. With these altarpieces, I wanted to apply this idea to painting: by opening or closing its wings, time and space unfold, a kind of stereoscopy is created, and the imagination wanders at will. With this in mind, the resurgence of certain motifs, the recurrence of their appearance, is inherent to my act of painting. It’s the off-screen material that keeps wanting to appear!

SH: Your signature large-scale brushes are central to your practice. How does the physicality of these tools influence not only your creative process but also your relationship with the abstract forms you depict? What does this scale and physical engagement bring to your exploration of natural forces?

FV: The reason I work with very large brushes is twofold. On the one hand, they allow me to play with the most essential force on earth, the force of gravity. All the forms around us are defined by gravity, and painting with tools and devices that rely on the principle of gravity for mark making brings me closer to the dynamism of forms, to the force that underlies them. Secondly, these very large brushes enable me to paint the shape and its outline at the same time. Let me explain: in traditional painting, the form painted on a canvas is made up of successive strokes or lines that gradually fill in the form or subject the painter wishes to depict. Many painters work from a previous drawing, and successively apply their pigments to the canvas, respecting as faithfully as possible the outline that has been traced beforehand. In my case, it’s a little different. I believe that the line of paint, in its width, its thickness, its vitality, its suppleness, must in itself embody the subject I’m trying to paint. A line suspended in the space of the canvas must be able to evoke, through its body, the reminiscence of a walk in the mountains, a trip to the sea, an afternoon lying on the grass watching the clouds, a summer night.

SH: Spending nearly a decade in China studying calligraphy has clearly left a mark on your practice. What was it about Chinese calligraphy that first drew you in, and how has that experience continued to inform the way you approach your paintings today? Could you share a specific lesson or moment from that period that deeply resonates with your current work?

FV: I wanted to go to China in the ’80s, because at that time, in art schools in France, painting was unfortunately being taught less and less, and was considered a somewhat outdated form of art. At the time, I was interested in things like the dynamism of birds, the speed of animals and more generally, the beauty of nature. I arrived in China after the ravages of the Cultural Revolution, and had great difficulty finding teachers willing to teach a foreigner, and a woman at that. The teacher who, after more than a year’s solicitation on my part, was kind enough to pass on his knowledge to me, explained that in China, painting is historically dependent on calligraphy, and that a thorough understanding of the pictorial phenomenon could not be conceived without first going through calligraphy. This was true partly in terms of the aesthetic and critical appreciation of works – without calligraphic training, the connoisseur’s criteria for judgment cannot penetrate the intimate architecture of the brushstroke. It was also true on a theoretical level, as Chinese pictorial treatises borrowed a significant part of their terminology, their aesthetic and technical concepts from calligraphic treatises. In the field of calligraphic theory, however, very little had been studied in the West at the time. Very few Western painters had studied in

depth the principles and aesthetic concepts underlying the practice of painting in China. So I spent almost ten years there, trying to approach this aesthetic tradition of finding vitality in a single brush stroke. On my return to France, I set out to transpose the knowledge that had been passed on to me and invent a new pictorial language, using new tools and materials and achieving a real change of scale.

SH: Your process of painting is highly physical, and many describe it as almost performative. How important is the act of painting itself in relation to the finished artwork? Do you consider the movement and energy in your studio as integral to the meaning of the final piece?

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot.

FV: The technical devices I’ve set up in the studio allow me the greatest possible freedom of movement in all axes of space. I need to be able to move my brushes without being constrained by their weight, so that once the canvas is pulled back up to be shown vertically, the greatest possible sensation of freedom and dynamism can shine through. The act of painting and the finished picture feel very close to one another, because the subject of the painting tends to be a kind of energy, and is closely connected to the energy that enabled me to paint.

SH: The notion of “emptiness” or “void” is prevalent in both Eastern philosophy and abstract art. How does the concept of emptiness influence your compositions? Do you view the space in your paintings as a form of presence or absence, and how do you balance this with your use of form and color?

FV: The notion of emptiness is essential for me. The void, that space left to the imagination, tends in the West to be no more than a support for the painted parts, whereas in the Chinese tradition, it is an essential aid, guiding the eye and bringing it to the threshold where the mind takes over from sight. In this tradition, the void is also constituted by the white of the paper, but I wanted to shift this notion of emptiness. The backgrounds of the Retables are no longer white, but radiant, apparently monochrome pigment surfaces that are in reality made up of a multitude of very thin layers of glazes and pigments, to create a vibratory space that welcomes the energy of the brushstrokes.

SH: You’ve spoken about the importance of ‘letting go’ during the painting process. How do you achieve this state of spontaneity, and what role does control—or the lack of it—play in your practice? How do you navigate the tension between intuition and precision in your work?

FV: Yes, “letting go” is fundamental. The brushstroke must be free and detached, otherwise the movement of life and the dynamism of form cannot be expressed. The painter’s imagination works on the basis of a motor schema, retaining, as a child retains movement patterns in order to make sense of the world, the living lines of nature. Each object, comprised of elements, is defined by the relationships between these elements, often in terms of movement. Thought registers these relationships, then closes in on itself and apprehends, beyond the relative, movement itself. The creative operation is complete when the image, seen by the mind, is as if born of it, and only that is when the brushwork can begin: it is from this letting go that, paradoxically, precision in the work can emerge.

SH: Many of your exhibitions respond to the works of other artists or historical movements, such as your exploration of Cézanne’s landscapes. How do these dialogues with art history inform your creative process, and what role does the past play in your approach to contemporary abstraction?

FV: I’ve always been struck by Marguerite Yourcenar’s phrase: “Looking back at history, stepping back to a past period […], gives you perspectives on your time and enables you to think more about it, to see more clearly the problems that are the same or the problems that are different or the solutions to be found.” Observing the old masters is very important to me. I’ve always believed that if you want to try and invent new things in painting, you have to immerse yourself in what your predecessors have done or sought to do. I don’t know if this is true in other arts, but in painting it forces you to understand the problems that painters have posed and the solutions they have found.

It’s only by taking a long look at a painting by Giotto, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Eyck, Cézanne, Matisse, Morandi or Rothko, that we can try to perceive the pathways that led the painter to choose this or that path. In each of their brushstrokes, there is an unceasing dialogue between figuration and abstraction. It’s this back-and-forth in the art of transcribing reality through the mind that fascinates and inspires me.

SH: Nature, in its many forms, seems to be a constant source of inspiration for you. Is there a particular landscape or natural phenomenon that has had a lasting influence on your work? How do these environments inform the energy and movement that are so characteristic of your paintings?

FV: Nature is my most essential source of inspiration. Whether you’re in the city, in a garden, in a forest, by the sea, in the mountains, every manifestation of life is captivating, whatever the scale of observation. In the Western tradition, human beings are usually the central subject of painting, occupying the foreground or foreground of the picture. Nature, on the other hand, is relegated to the background or the edges of the canvas. There are, of course, naturalist painters, but their work is referred to as “still life” or “landscape”! With the climate upheavals we’re facing, it seems appropriate to me to leave our anthropocentric position and put nature, biodiversity, living things in all their forms, back at the heart of our concerns. That’s why, in my very modest capacity, I endeavour to paint the beauty and dynamics of living things. To observe and contemplate is a step towards becoming aware of the poetry of the world, something I would like to pass to future generations.

SH: Your work often engages with the unseen—whether it’s forces like wind and gravity, or metaphysical ideas. How do you go about visualising these invisible dynamics? Do you think of your work as a translation of these forces, or is it more of an abstract meditation on their presence?

FV: I recently worked with an Honorary Professor at the Collège de France, Professor Alain Berthoz, who is a brain specialist. His research focuses on how the cerebral cortex organises, anticipates and orders our body’s movements. He explained to me the extent to which our brain and the information it stores, in the form of memory in particular, actually create the tools for thinking about the future. Memory is not for remembering, but for predicting. Laboratory experiments carried out a few years ago show the importance of neurons called “mirror neurons”, which indicate that seeing a shape in motion sets the brain into action in the same way as if the body were physically moving. I think about this in relation to the painting of forces such as wind or gravity: the viewer, seeing a vortex rise or following with your eyes a “walking-painting” traversing the space of the canvas, is already taking flight and walking! It is a powerful shared dynamic between body and painting.

Words by Sofia Hallström