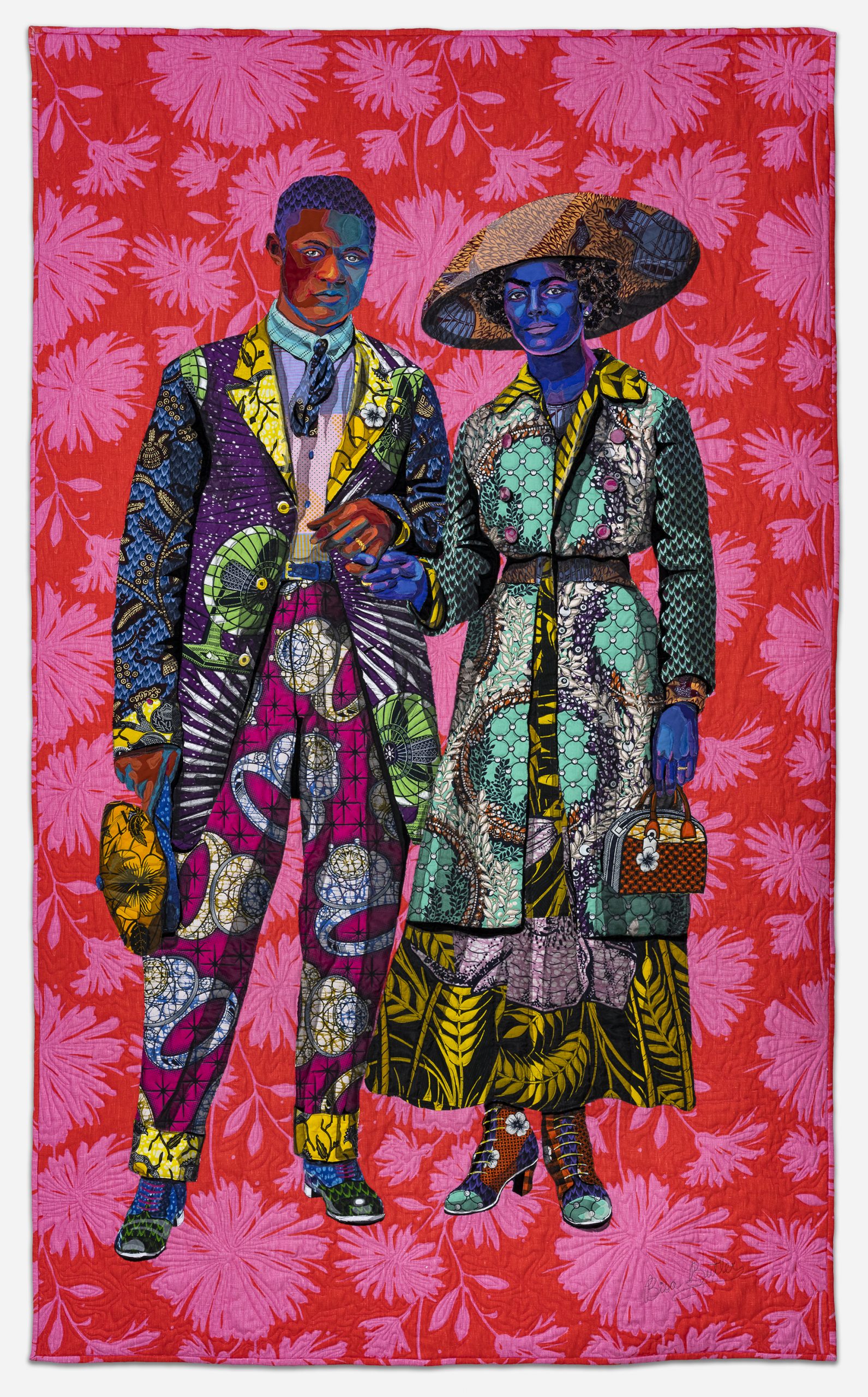

“Bisa Butler is not a quilter. She is also not a photographer,” declares American Federation of Arts curator Michèle Wije, situating the New Jersey-born artist in an interdisciplinary space before clarifying that her practice is still “indelibly rooted in both of these media.” Butler uses a range of historic photographs as her sources which she then reconstructs in fabric, her method drawing parallels with painting for its liberal and vibrant use of material and colour.

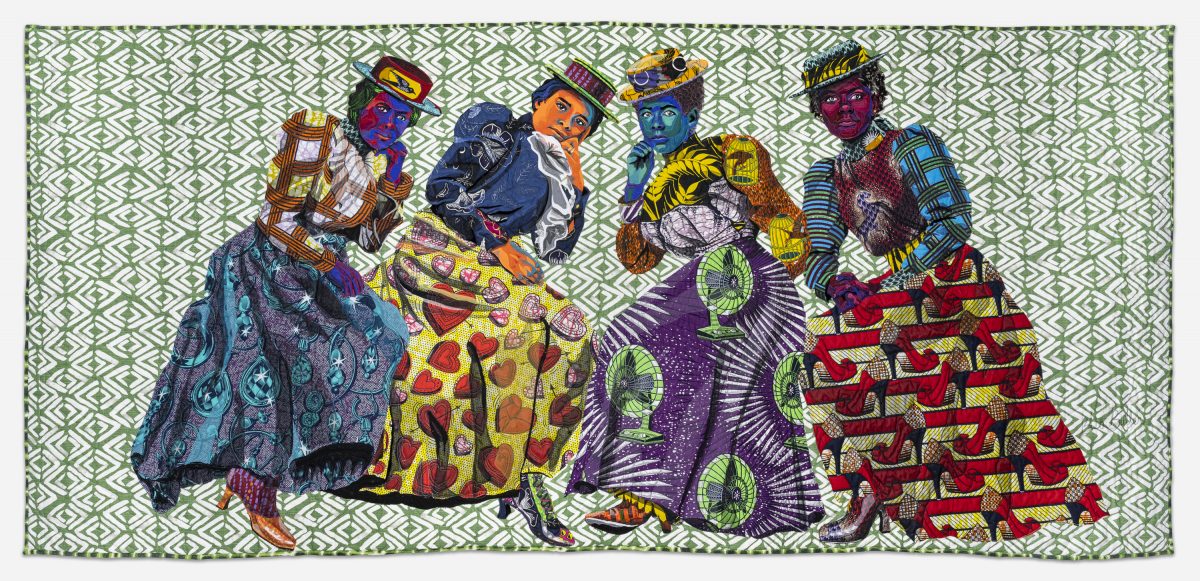

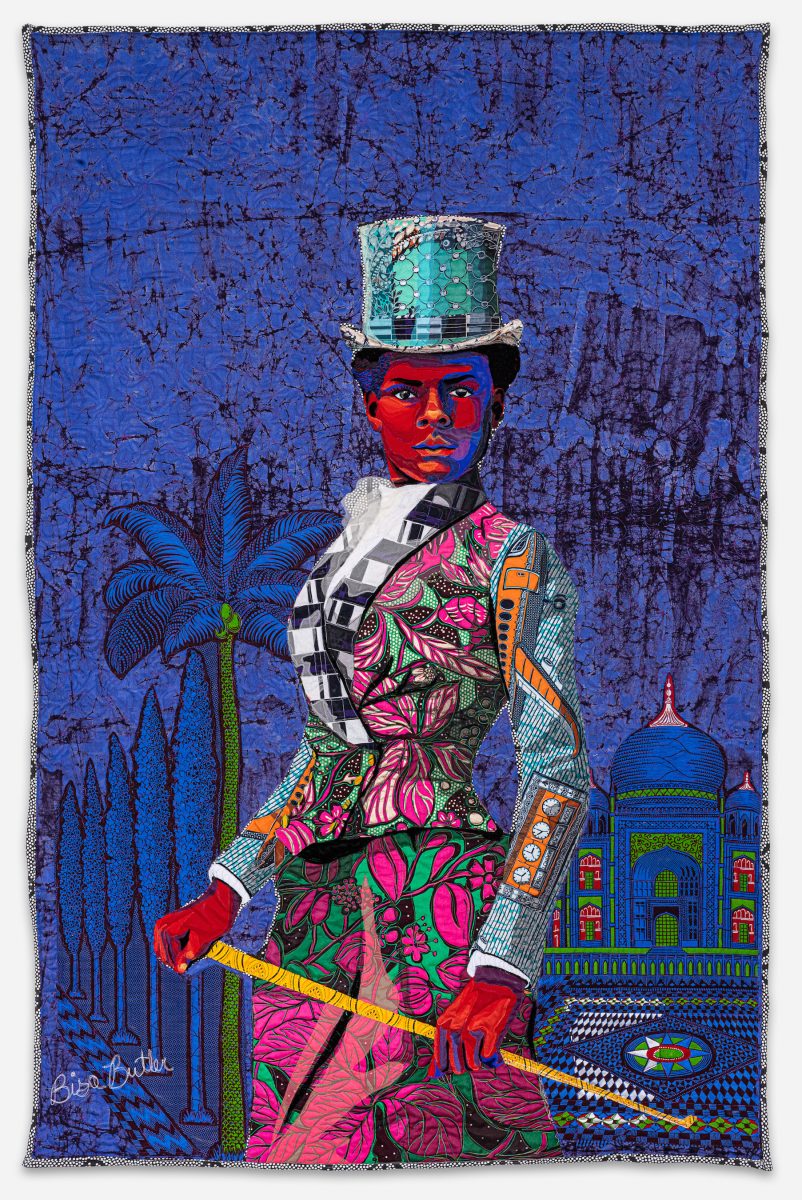

Butler’s recently extended

Portraits exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago showcases a style that is both transformative and maximal: black and white photographs are re-energised with an array of textile styles and patterns, often drawing from the West African tradition or the last century of African-American history. In I Am Not Your Negro, Butler adapts Dorothea Lange’s photograph Negro in Greenville, Mississippi (1936) to include striped orange trousers bearing an aeroplane pattern to signal migration and journeying: “he, like James Baldwin, is an expat,” she explains. Butler borrows the title from Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary, playfully updating Lange’s subject while rooting her version in a shared, and as yet unresolved, racial climate marked by hostility.

“I’m interested in the human contribution, how we see things. I think the more we rely on technology for art, the less humanity it has”

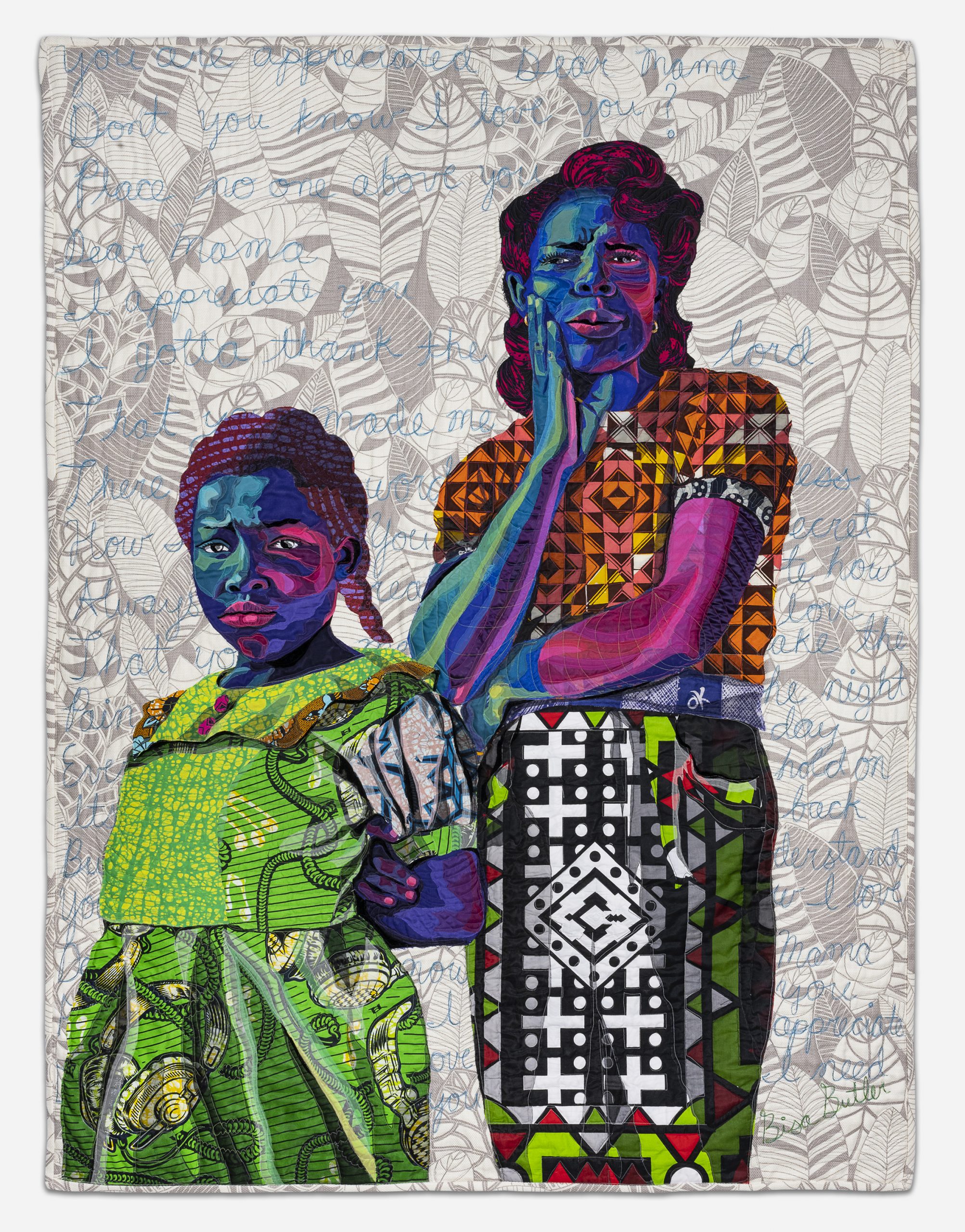

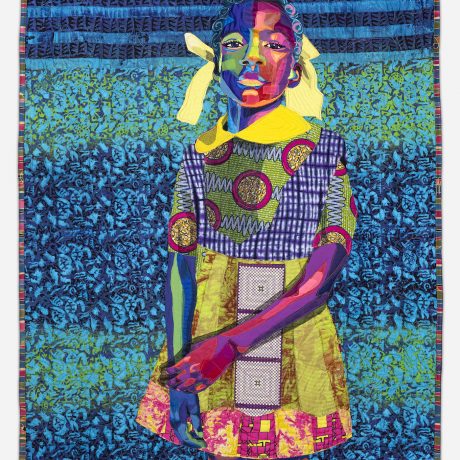

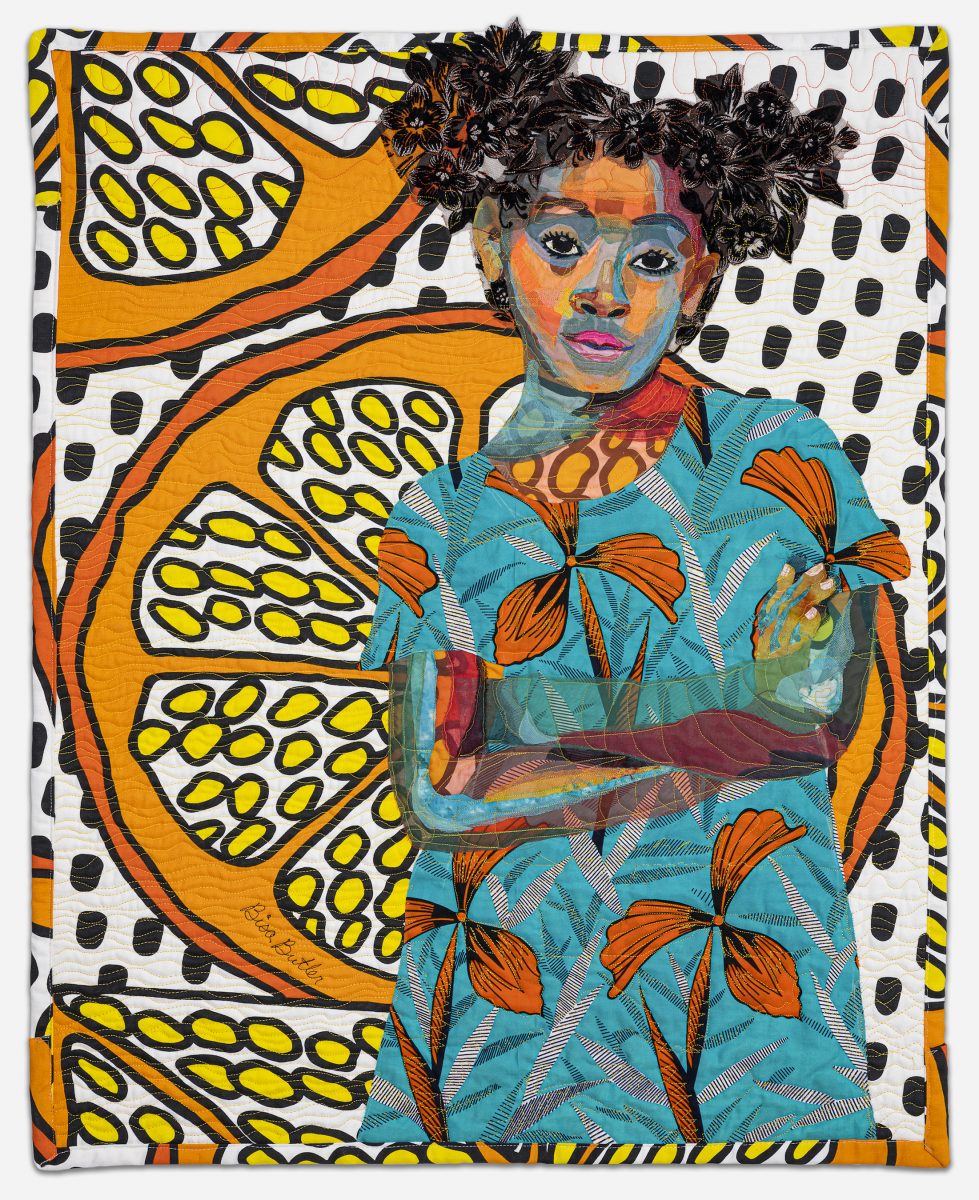

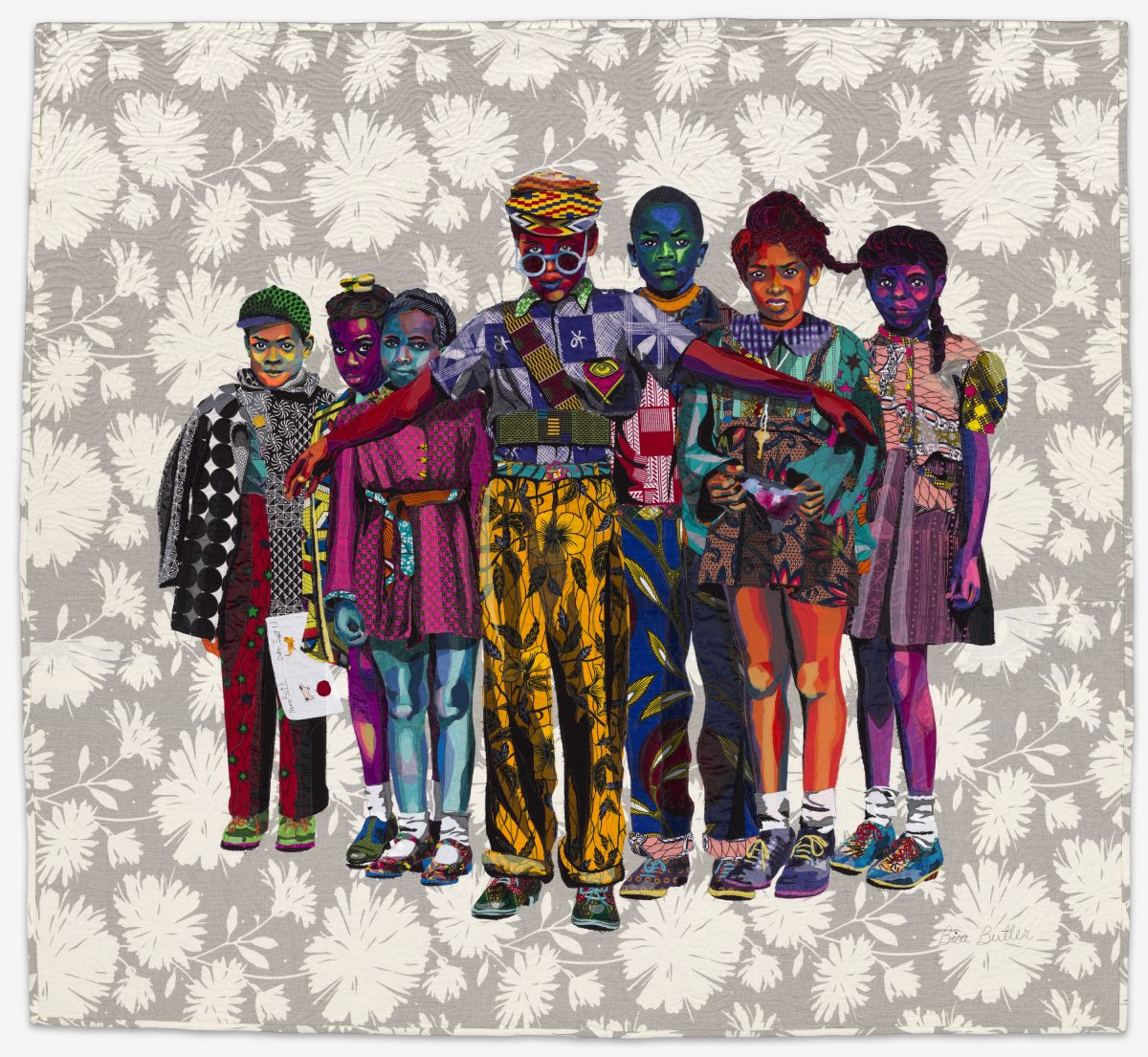

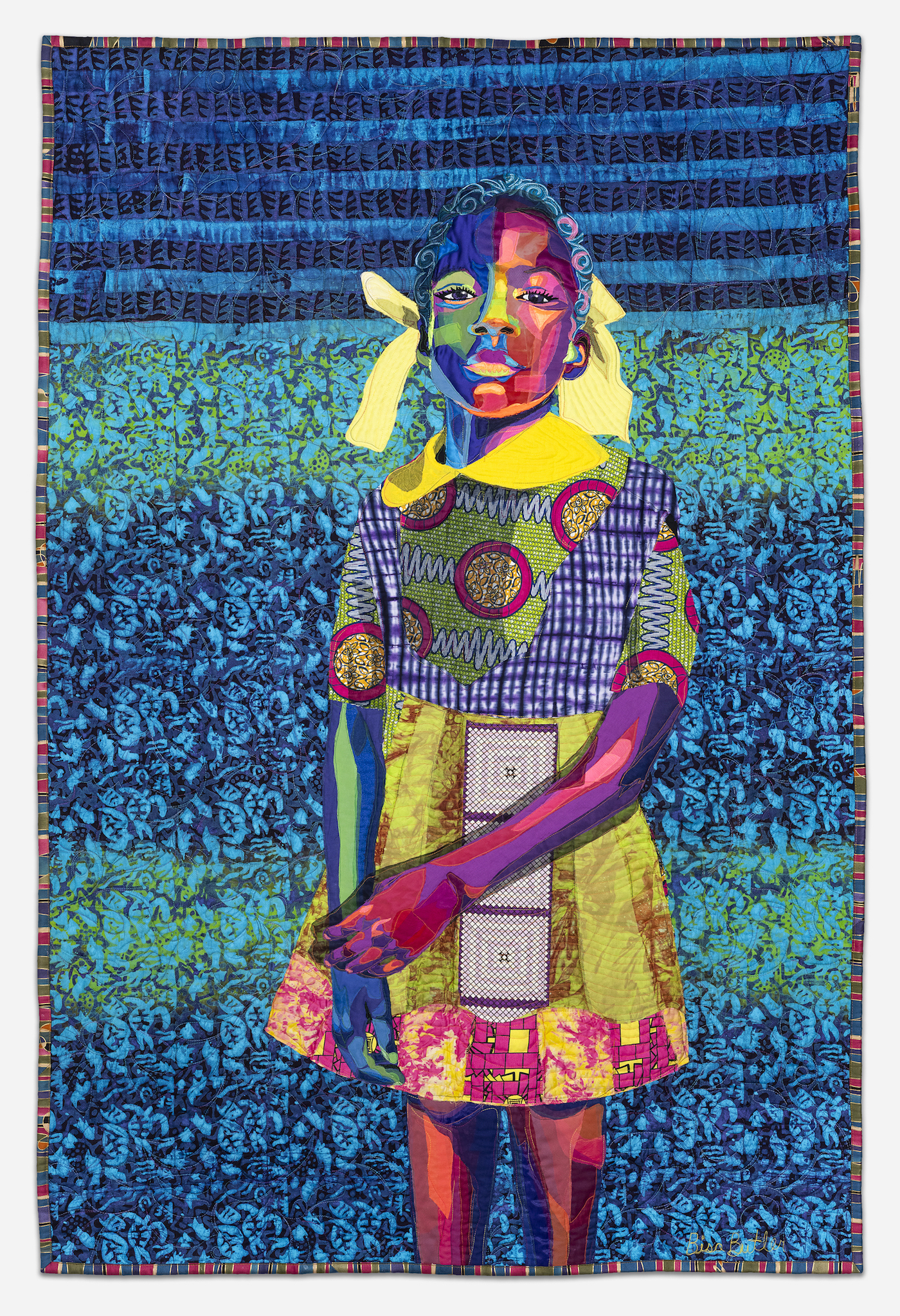

“The photograph is already a mechanical process of flattening a three-dimensional object and then re-creating it on a two-dimensional surface,” Butler explains in the catalogue. “I’m interested in the human contribution, how we see things. I think the more we rely on technology for art, the less humanity it has.” Such humanity is evident in Butler’s more intimate selections, especially of children. The Princess is a portrait of one of Butler’s friends when she was six, about to emigrate from Jamaica to the US, the scene reconstituted anew with a variety of West African Dutch waxes and Ghanaian wax prints. Anaya with Oranges mirrors this youthful trepidation but on a far more innocent scale: the artist’s seven-year-old goddaughter captured in the morning before heading to school.

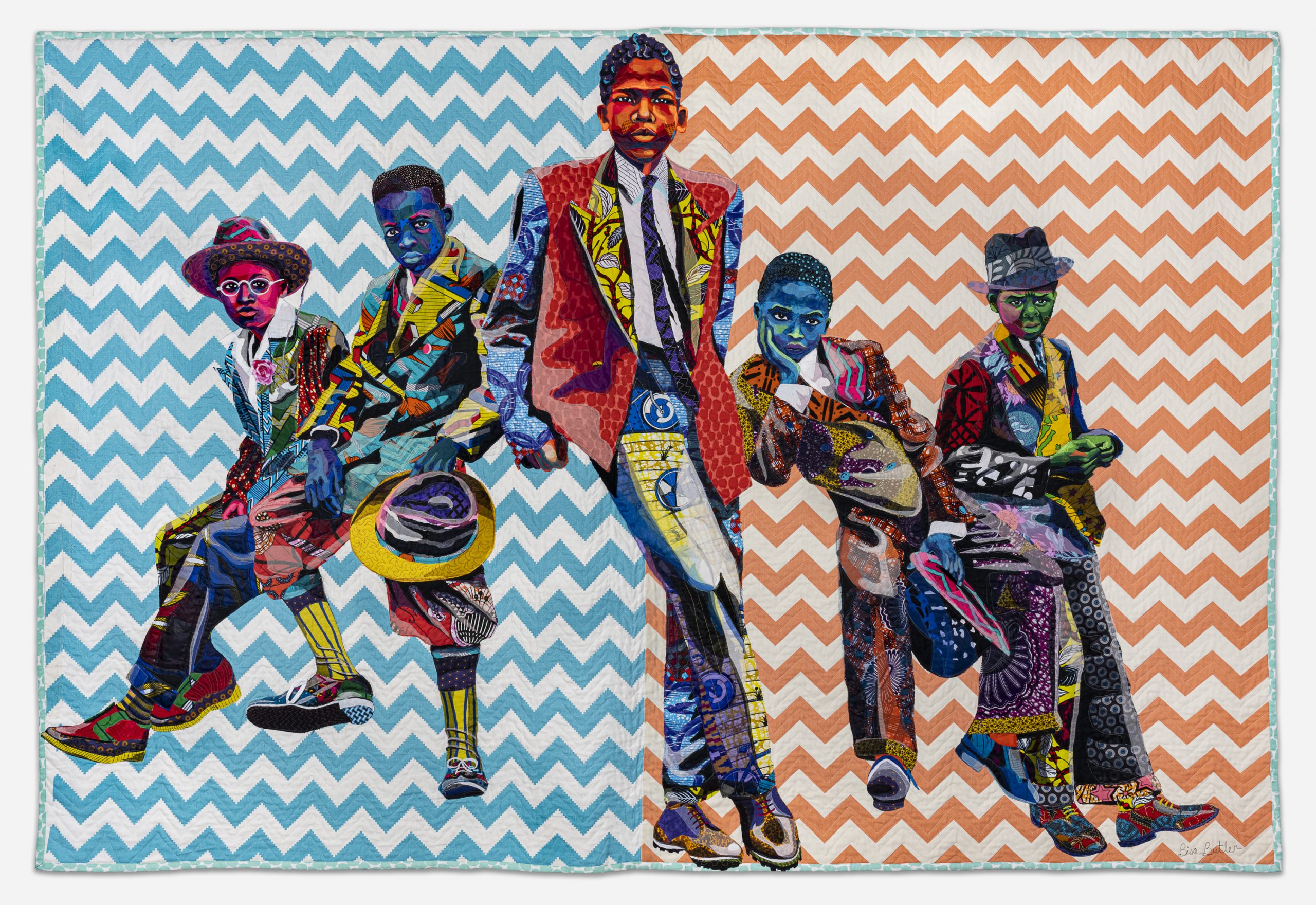

This sentiment also leads Butler to omit objects from the original photographs in order to focus attention on her subjects. Southside Sunday Morning uses Russell Lee’s Negro Boys on Easter Morning, South Side, Chicago (1941) as its photographic source, but by removing the hulking car bonnet from her rendering, Butler creates the illusion of a floating troupe—the boys still in their cheeky poses and Sunday best suits, but now against a stamp-like backdrop which seems to lift them into stardom.

Despite extensive archival work, the difficulty of identifying the figures in the original photographs allows Butler to construct identities for them using her textiles and chosen influences. In The Safety Patrol, the central figure wears a kente cloth sash from Ghana, the artist’s ancestral homeland. In I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, the shiny earrings on the first figures evokes the wealth of West African cultures, while the birdcage on the third girl’s arm (along with the work’s title) reference Maya Angelou’s autobiographical work. Unsatisfied with simply spelling out these references in supplementary text or descriptions, Butler’s subjects wear her influences like an extra set of clothes, textile layering becoming a process not just of reinvigoration, but of cross-fertilisation too.