We all have a story to tell, and Faith Ringgold’s is one of courage and life-force. With multiple dimensions to her sixty-year oeuvre, the octogenarian artist’s far-ranging practice encompasses painting, drawing, sculpture, quilting and activism. As a young Black woman growing up in Harlem (she was born there in 1930 during the Great Depression) the artist battled racism and sexism. In 1950, for example, she was refused entry into New York’s City College because the school of liberal arts did not admit women, a technicality she circumvented by majoring in art education.

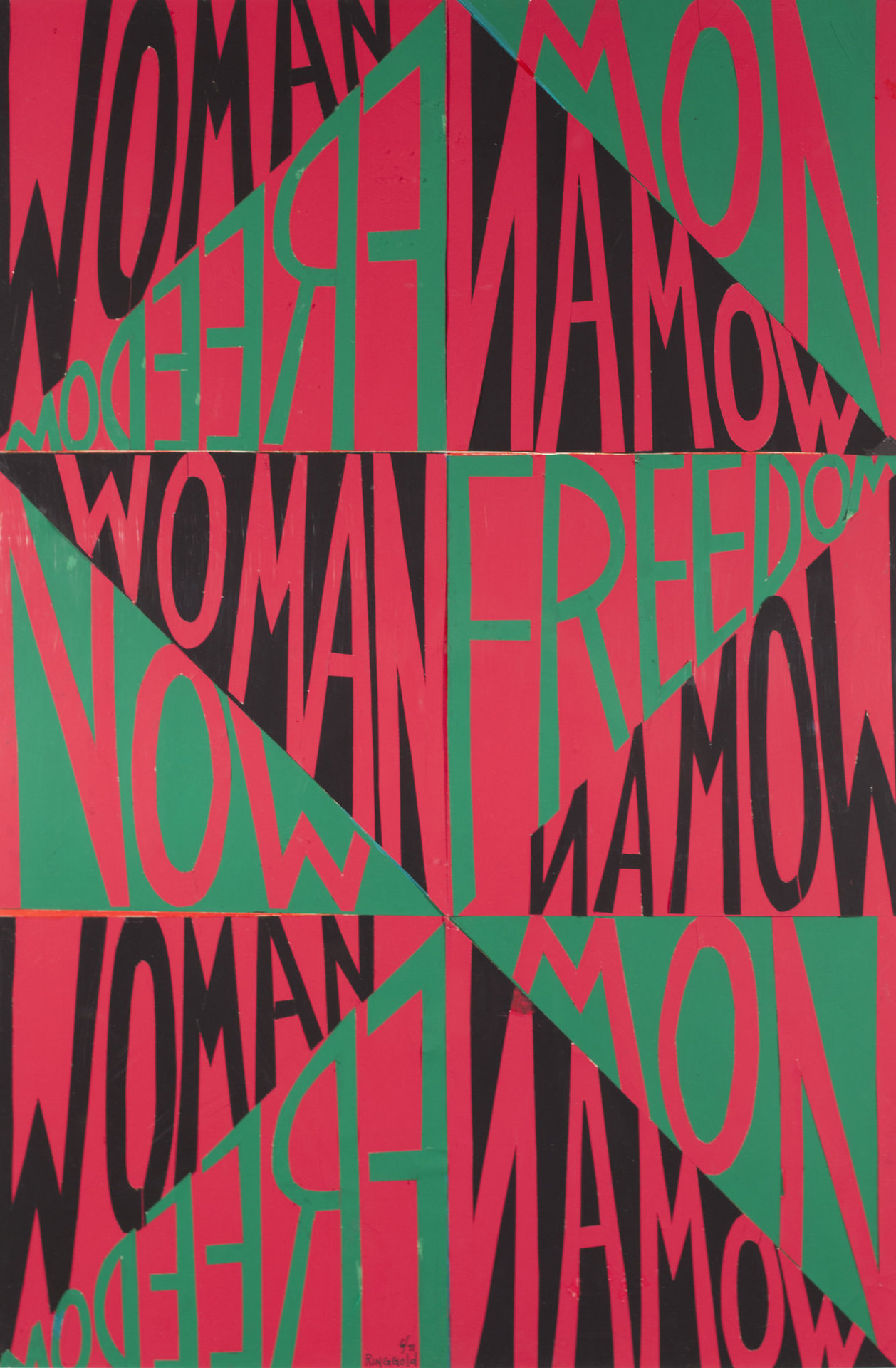

As such, identity and gender politics are literally sewn into the fabric of Ringgold’s work, from her homage to the gay rights activist Marlon Riggs to her depiction of Martin Luther King in a Birmingham jail in Alabama. The artist has always refused to accept the status quo. She protested with critic Lucy Lippard in the 1960s and 1970s against male-dominated exhibitions at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, and the fight for equality has become enmeshed with her work.

In considering how far we’ve come, Ringgold is cautious. “Two steps forward, one step back,” she says. “We have made progress over the last hundred years but there is much more work ahead to overcome social injustice and gender inequality. Whenever I experience racism or sexism, I express it in my art—always showing optimism. I like to turn wrong into right in a positive way. This can be seen in my Coming to Jones Road series, which explores the Underground Railroad.”

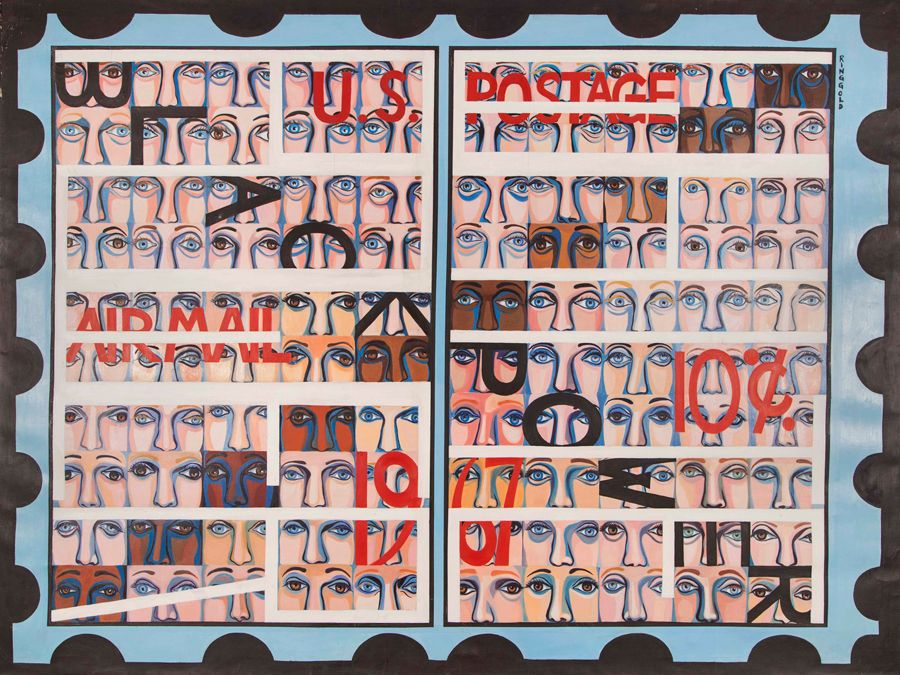

American People Series #9 The American Dream, 1964

It was in 1963 that the artist began making her Black Light series, created to express herself as a Black woman living in America. It also sought to celebrate what she has termed a “Black aesthetic”, highlighting how “different ethnicities have different looks. You can look at a person and know right away the characteristics that make them unique. In the 1960s I wanted to capture black skin on canvas. When I saw the Black paintings by Ad Reinhardt

, I was inspired to experiment with different dark hues, to see how best to paint black skin.”

“Whenever I experience racism or sexism, I express it in my art, always showing optimism. I like to turn wrong into right in a positive way”

Her painting American People #19: US Postage Stamp (1967) (a work depicting a proportional grid of faces to underline that black Americans comprised 10 per cent of the population) included the words “Black Power” inscribed at a diagonal across the canvas. The work was inspired by civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael shouting the phrase on television.

In an interview with the Serpentine Galleries, Ringgold described her response at the time: “I said, ‘Black Power? We don’t have any power, what is he talking about? He’s making that up.’ But it caught on and everyone was shouting, [the phrase].” She adds, “So how do you get any power from being 10 per cent? Well, you get [it] from having all 10 of those per cents speak up. That’s been my life actually: working, working, working until I get it done.”

It was the spirit of female collaboration and hard work that led her to make her first quilt, Echoes of Harlem, with her mother in 1980. “My mother meant a great deal to me. I don’t know whether or not I would have been able to understand how to make quilts or any aspect of sewing without her,” she explains.

“In the 1930s, mothers taught daughters how to sew. People took pride in wearing hand-sewn original garments.” She continues, “It was also a time when women took a back seat to men and supported them from behind. My mother never worked until World War Two, when she was enlisted to sew Eisenhower jackets and parachutes for the war. She also learned from her mother; she loved sewing and, given the chance, ran with it!

“In the 1930s, mothers taught daughters how to sew. People took pride in wearing hand-sewn original garments”

“After that, my mother attended the Fashion Institute of Technology, learned how to make patterns and became a fashion designer. She was a perfectionist, unique and powerful; she was a superwoman. A gracious host, she entertained all the time, kept the house spotless and raised a family. I learned a lot from my mother, [she] gave me my work ethic.”

Describing the issues that led to her making her first works in fabric, Ringgold emphasises, “I wanted to create sculptures but could not use the usual materials such as stone and wood, as I had asthma and could not tolerate the dust. With my mother’s help, I created soft sculptures using fabrics and mixed media. There were a lot of extraordinary characters in the 1960s and 1970s and I wanted to capture them in a three-dimensional format.”

In using appliqué as her medium, Ringgold patched together brightly coloured blankets and painted them with figurative scenes that reflected these histories, calling them “Storyquilts”. She also crafted masks and soft sculptures using materials such as velvet and shells. Moma in a Chair Reading to Her Three Children (1980) is a sculpture that includes a tiny stitched storybook (written by Ringgold herself) titled Do You Love Me?, from which Moma recites to her wide-eyed babies.

“I wanted to create sculptures. With my mother’s help, I created soft sculptures using fabrics and mixed media”

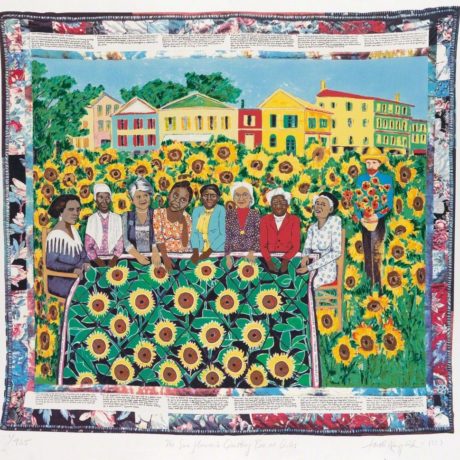

More recently, Coming to Jones Road Part II #7 Our Secret Wedding in the Woods (2010) depicts a couple being married by a minister, accompanied by a small congregation under a canopy of yellow and green leaves and a carpet of flowers underfoot. Its mood is one of joy and reverence, a private, magical moment to which we bear witness. The second in Ringgold’s Coming to Jones Road series, which she started in 1999, is about Aunt Emmy (her great-grandmother) who escapes a plantation in search of liberation from slavery.

Jones Road refers both to Ringgold’s maiden name and to the New Jersey address to which she moved in the early 1990s, where she experienced hate and hostility. The Jones Road story, conversely, is one of optimism and hope, the will for progress winning out over the tainted reality. After all, although often fiction, creative writing provides tangible models which we can learn from and apply to the everyday.

Does fiction exist for Ringgold, or is everything rooted in the real? Why did she choose storytelling as a mode of expression and a form of representation? “I was brought up with storytelling,” she tells me.

“When I could not get my autobiography published, I decided to write stories on quilted canvases”

“When I was a child living in Harlem, all sorts of interesting people—relatives and friends—would stay at our house after their journey north. Sometimes it would take them months to make the journey from the south, and the stories were intriguing. We had to stay quiet as children otherwise we would have to go to bed. I learned a great deal from hearing about the trials and tribulations they encountered. When I could not get my autobiography published, I decided to write stories on quilted canvases. Many of these stories are based on actual characters but embellished with fantasy and fiction.”

This work, like most of Ringgold’s Storyquilts, is surrounded by a border inscribed with the tale. Visiting Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum in 1972, she saw Tibetan “thangkas” (paintings on cloth with a silk brocade frame). Captivated by their composition, she began to integrate this ancient format into her own work, narratives enclosing her painted world, which draws so potently from the real one. In Ringgold’s own words, “Anyone can fly, all you’ve got to do is try.”

Louisa Elderton is a writer, editor and art critic from London, living in Berlin

This article first appeared in Elephant 42