When the American photographer Larry Sultan published his photobook Pictures From Home in 1992, he spoke of wanting to deconstruct the idealised image of the institution of family life as it was being pedalled in Reagan-era USA. “I wanted to puncture this mythology of the family,” he wrote.

Sultan was willing to use his own family to prove his point. With muddled affection, he had spent the last ten years photographing the dynamics of his relationship with his parents. The resulting body of work was, in some ways, an alternative family album. “What drives me to continue this work is difficult to name,” he said, “but it has more to do with love than with sociology. With being a subject in the drama rather than a witness.”

Recently, a small constellation of photography projects have emerged that re-examine the idea of the family. Some of these artists and photographers shoot their own families, making their personal history the subject of the drama. Others turn their lens on the dynamics of other families, looking in from the outside upon close-knit, often difficult relationships.

These artists tease out the awkward mechanisms of contemporary domestic life through the camera. Though markedly different in their individual perspectives, there are some aesthetic approaches they share: each creates portrait-based pictures shot around the home, moving between performance and voyeurism, with a focus on gesture and body language. So what is it about the subtle tensions of home environments that grips our collective imagination?

“Our experiences and emotions are housed in our bodies. I like to show interactions between my family through touch, gesture and body shapes”

For Polish photographer Joanna Piotrowska, our homes are microcosms, speaking to the way we form our own identities within the context of the family. “Domestic space is governed by hierarchies and complex dynamics which are often mirror-images of ones present within the public sphere,” she says. “Politics and history reside not only in a private home’s furnishings and objects, but also within family relationships, games, gestures and everyday situations.”

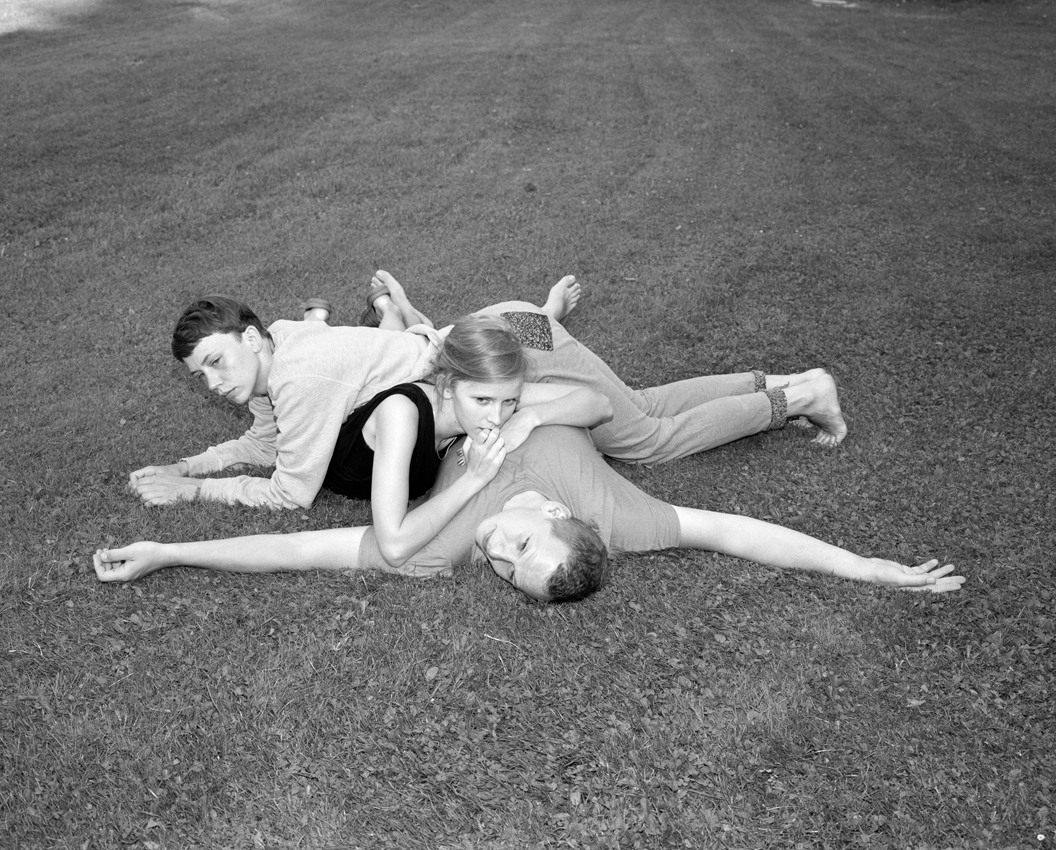

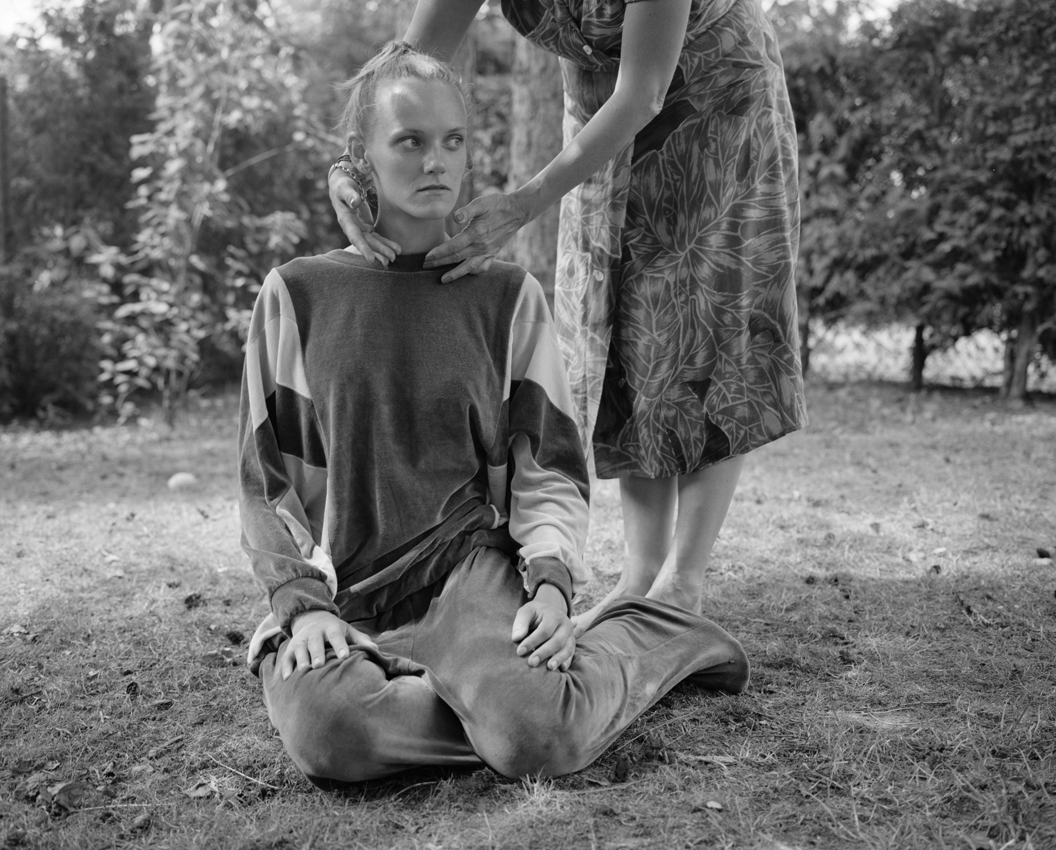

In her 2014 photobook Frowst, Piotrowska presented highly staged images of real family members interacting in uncomfortable ways in household settings. Her models bend their bodies across one another, grip each other’s wrists and hold strained poses as the shutter clicks. Their body language visualises the fundamental anxiety at the heart of family life, she says. Her choice of a monochrome palette and a heavy flash flattens the images. Individual bodies coalesce with interiors, and those strange gestures become the full focus of the pictures.

For twenty years Gillian Laub took pictures of her well-off American Jewish family to make sense of her relationships with them and with the world around them. She found that this helped her to better understand the reasons for her views on everything from money to religion. Then, in 2016, when Trump took the presidency, she found herself at odds with her parents, on opposing sides of the political spectrum. Her photographs of them shifted and the camera became a mediator in a divided time.

“One of the reasons I felt so compelled to share this story is because I knew how many others were experiencing similar dynamics,” she says, “I kept hearing the words of a professor at art school who always said, ‘The closer and more specific you get, the larger the story you have to tell’.” As with Piotrowska’s images, there is an aesthetic tension running beneath Laub’s work, cleverly hidden in awkward groupings or telling looks between family members.

Laub’s resulting photobook Family Matters (published last year) is like a delicious drama, critical and comedic, split into acts with characters we come to know. But where Laub gives us a peek behind the curtain of privilege, other artists conjure narratives from the bland familiarity of of American suburbia.

“Family dynamics within the home are often overlooked, seen as mundane and easily taken for granted,” says Jarod Lew, whose project In Between You and Your Shadow centres on his Detroit family house. Commissioned by Aperture in 2021, the series was born from the Chinese American photographer’s shocking discovery in 2012 that his mother had previously been engaged to Vincent Chin, the Chinese American draftsman who was murdered in 1982 in a racially motivated attack.

- Left: Gillian Laub, Chappaqua backyard, 2000. © Gillian Laub; Right: Grandpa helping Grandma out, 1999

It was a watershed moment in Asian American civil rights, and Lew wanted to use his camera to explore the trauma that still hung in the air of his quiet home. Due to his mother’s aversion to the camera, he sought out alternate methods of filling the pictures with her presence. “I wanted to respect her wishes by sustaining the mystery around her, covering her face in myriad ways,” he explains. “This paradoxical approach of visualising the invisible became a critical aesthetic for exploring the hypervisibility of racial trauma, intergenerational conflict, and my relationship with my mother.”

“I’m interested in the way family members’ gestures and expressions are tied together in a continuum of sorts”

Lew’s portraits see his family members posed in ordinary domestic interactions while their shadows loom across the walls, adding visual drama to everyday life. Lew includes an arm holding a flash in some images, which helps, “to situate the viewer within the constructed scenes, as an invited guest,” he says. It is a strategy akin to breaking the fourth wall, and reveals the scene as a staged set.

Ohio-born Ashley Markle takes a similar approach. In her project Weekends With My Mother and Her Lover she explores the dynamics between herself, her mother and her stepfather. The cable release is often visible and never allows us to forget the camera’s existence.

In Markle’s world, gestures like a mother feeding her child become charged and exaggerated through their staging. “I believe all of our experiences and emotions are housed in our bodies, so I like to show interactions between my family members through touch, gesture and body shapes,” she says.

Her pictures can make uncomfortable viewing. They dissolve the polite poses we might expect to see in family photos. “My family picture has changed a lot over the years,” she says. “My father and mother were divorced when I was five, then my mom met my first stepdad, and after that John came into the picture. I think that’s the reason I’m so interested in family dynamics, because they have been so prevalent in my life.”

Tealia Ellis Ritter, whose photobook The Model Family has just been published, has a similar impulse to dissect the nuclear family image. In black and white photographs spanning 30 years, The Model Family is an exquisitely told story of intergenerational loss and love, capturing everything from slow summer evenings to funerals and divorce.

“Family dynamics within the home are often overlooked, seen as mundane and easily taken for granted”

“I’m interested in the way family members’ gestures and expressions or manner of moving their bodies are tied together in a continuum of sorts,” she says. “I like that it can become confusing as to whether you are looking at my daughter or my sister or my mother, as if one is becoming the other over time. Even if their bodies aren’t occupying the same space, they are bound together by way of gesture and physicality.” Our loved ones, at times, can become mirrors of ourselves.

Piotrowska’s images “teeter on the edge of the dysfunctional moment”, while Lew reminds us that “family photos have a way of capturing that polarity between love and conflict.” That’s the thing about families. Relationships criss-cross between generations, bound by love and history. They shift between reward and frustration, at once comforting and stifling.

Each of these artists visualises those invisible dynamics in scenes both choreographed and raw. Theirs are chronicles of the nebulous ways in which familial relationships continuously evolve.

Joanna Cresswell is a writer and editor specialising in art, literature and culture