In the last weekend of August, a crowd descends on the quiet Welsh village of Berriew. They dress in velvet tunics and huge jewels that look more like talismans, with burning suns, unearthly flowers, big green eyes and mirrored spiders featuring prominently.

They dance on the banks of the River Rhiw where picnickers normally sit and swimmers dry off. In front of them a faux pearl-encrusted boat glides through the water, pulled by a hooded figure. On the boat, drag performer Fancy Chance reclines wearing a thick, pearl strewn plait so heavy and long that it will need to be man-handled by several helpers when she finally docks.

In most rural farming communities, this might cause a stir. In Berriew, such scenes are par for the course in the village’s annual flamboyant parade known as the jewellery extravaganza.

It is organised by the Andrew Logan Museum of Sculpture, which sits just behind the river and claims to be the only museum in Europe devoted to a living artist. Housed in a former squash court, it holds work by sculptor, jewellery maker, and Alternative Miss World founder Andrew Logan.

Its contents run from a 12-foot-high Cosmic Egg

constructed from mirror shards to portraits of Lady Di, Divine, and Vladimir Putin. It’s an unassuming setting for Logan’s unique blend of spangled high camp and ambitious sculpture.

The museum opened in 1991, hence all the pearls, the traditional marker for a 30th anniversary. Logan has approached the occasion in typically flamboyant fashion by scattering pearls over every surface. There’s also a new sculpture in the museum: Life and Oomph depicts the dancer Lynne Seymour soaring above an iridescent sea of pearls.

Logan’s sculptures have stood everywhere from the National Portrait Gallery to Heathrow Airport, and he’s collaborated with designers and brands include Bill Gibb, Comme des Garçons, Ungaro, and his close friend Zandra Rhodes. He specialises in mirror, glass and found objects, combining a magpie-ish love of glitter with an irreverent approach to images from myth and pop culture.

“My work is about joy and celebration of life,” he explains several days prior to the extravaganza, when we meet beside the Cosmic Egg. Now in his seventies and a lover of “organised chaos”, Logan has form when it comes to raucous event planning.

“To me, it has always been important that art should be shown everywhere”

In 1972 (the same year as the first Gay Pride march) he founded Alternative Miss World in London. This anarchic dress-up contest was driven by a spirited sense of the outrageous, attracting judges, contestants and attendees including David Hockney, Ossie Clark, Leigh Bowery, Divine, Vivienne Westwood, and Grayson Perry. Derek Jarman won as Miss Crêpe Suzette in 1975.

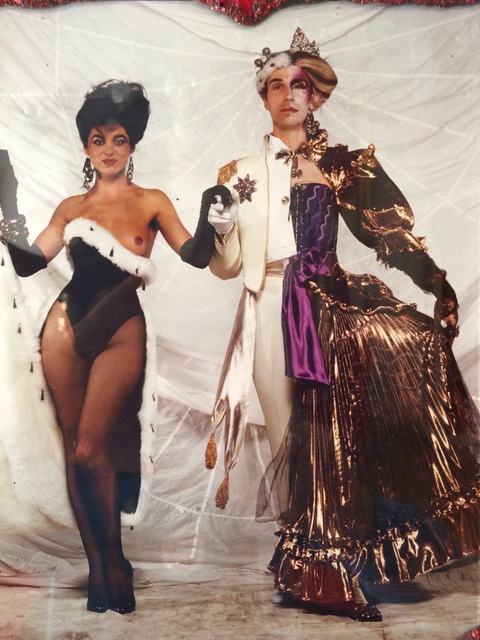

In the museum, up near the ceiling, a glass cabinet contains the half-and-half costumes worn by Logan in the role of host/hostess of Alternative Miss World. Huge photos of him also hang on the walls in frames garnished with gold spray-painted Barbies: a style known affectionately by the museum staff as ‘Logan Rococo.’

I grew up nearby and as a child Berriew was a neat day out: a swim in the river and a poke around the museum, followed by an art project at home where my mother would pull out old CDs to cut up and mosaic back together a la Logan. As a teenager I took part in the jewellery extravaganza, wearing half a plastic horse around my neck.

It was only later that I realised that this eccentric local attraction was actually somewhere of real cultural significance, holding histories (of art and fashion, of queer figureheads and communities) made all the more remarkable by being in a place where difference is not always tolerated.

“My ashes are going to be here in the museum, with everything I’ve created”

Logan first discovered the area when friends of his were house-sitting a nearby farm owned by Julie Christie. He’d always dreamed of a museum, but it wasn’t possible in London. When they finally found the right building, architect Michael Davis (Logan’s partner) designed the space.

For years they shuttled back and forth between London and Wales, but now the pair live permanently in Berriew. They recently bought the nearby Lion Hotel pub and guesthouse, revamping it in Yves Klein blue and placing Logan’s art in every room. “To me, it has always been important that art should be shown everywhere,” Logan says. “This is [another] a way of showing it… Even if they’re not looking, it’s there.”

Logan cares about reach. It’s why he’s worked on so many public sculptures. It’s why the museum has a section dedicated to children’s drawings, his headless fountains and kitsch crown jewels reimagined in crayon scribbles. It’s why he does the extravaganza every year. It’s a philosophy underpinned by a relentless work ethic and a puckish sense of play: “I always say that to young artists: open yourself up, and things will pour in”.

“My work is about joy and celebration of life”

After speaking at the museum, we drive to the barns on a nearby working farm where Logan stores his pieces. It’s a warren of stairs and sculptures, full of mirrored thrones and homages to old friends and loved ones: Maggi Hambling holds a cigarette complete with a wisp of wire smoke, while Logan’s parents are commemorated in a mosaic made from their china tea set. From the windows, one looks out through a bust of suspended crystals at tractors rolling through green fields.

There’s a great current appetite for revisiting queer histories. Visiting Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, for example, has practically become a rite of passage. “It’s so sweet,” Logan laughs, “because the one thing Derek wanted was to be a legend.”

Will others in future make similar treks to this small Welsh village? If Logan has his way they’ll be greeted with a library of his arts books and catalogues (currently in boxes reaching up to the barn’s ceiling), and a new museum front entirely covered in eyes.

Logan also plans to never leave. “I’ve made a little Cosmic Egg

, about half a metre high, which is going to hold my ashes. They’re going to be here in the museum, with everything I’ve created… I hope it will just bring a smile to the world.”

Rosalind Jana writes on fashion, art and culture. She is a contributing writer at Vogue Global Network and a columnist for Magnum Photos