You head to an island on the coast of Florida, taking some paintbrushes and a copy of the collected essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson. You’re going for what might pass today for some transcendental solitude, a hopeful encounter with a simulacrum of frontier wilderness in contemporary America. The island retreat is called Captiva, which is named after an eighteenth-century Spanish pirate, José Gaspar, who supposedly held a bunch of female prisoners there for ransom and whatever else took his fancy. Gaspar, known popularly as Gasparilla, might be an apocryphal figure, but he’s embedded in Floridian folklore.

Meanwhile, if you’re the New York-based artist Jack Pierson, you’re also embracing other, more modern myths, ones that have immediate cultural currency, like those concerning the “Great American Artist”. Captiva was where Robert Rauschenberg set up his home and studio in the early seventies and from where he produced works such as the beautifully billowing sailing-cloth series, Jammers, in celebration of his new island life. These were far removed from the grubbier aesthetics of Rauschenberg’s earlier combines, made in the days he used to scour the streets of downtown Manhattan for discarded bits of junk.

Pierson doesn’t have that much to say about Rauschenberg. Instead he talks of his enthusiasm for Rauschenberg’s one-time assistant, Brice Marden, and it’s an admiration that’s only in small part to do with his paintings. He mentions Marden’s rugged good looks and his apparently wild temperament. And you understand that the older artist is just enough under the radar of public perception for Pierson to feel comfortable being an unapologetic fan. For Pierson, Marden perhaps appears the embodiment of the “Great Enough American Artist”, one who is just that bit more attainable as an ideal than the bigger guys. “He makes a fortune and he’s handsome and, you know, has this whole bohemian background. He’s like the ultimate for me,” Pierson muses.

But what Pierson produces on the island looks nothing like Marden’s intricate spaghetti loops. In fact, it looks nothing like anything he’s ever done before. What he produces is a series of tiny, nimble, abstract paintings, ones with a variegated palette but which are largely bright and pastel-hued; abstract, but which nonetheless hint at Florida’s abundant subtropical flora. They strongly bring to mind early American pioneers of abstraction: Arthur Dove, for instance, and hints of Marsden Hartley. Though you’ll find both of these artists on the walls of the Whitney Museum, their names mean very little outside of it, even in the context of American art history. They are not the big heroes of American painting. Was Pierson deliberately channelling them as he was painting?

Pierson speaks slowly, with a long nonchalant drawl. There’s hesitation and occasionally lengthy yes-no backtracking, which is how he responds to the question, before finally settling: “I don’t think I was particularly aware of it, but Dove is someone I really like, or have liked. He was one of the first artists I knew of.”

The paintings and the drawings for this series, which he exhibited at Cheim & Read, New York, in 2015 with the title onthisland, were painted quickly, informed by his recent experiments in automatic drawing, another trope of the earlier modernists. “My only recipe for those paintings was to just sort of sit and complete the work as I did it, and try not to throw too much away—figure it out on the page, somehow. I’m not interested in the kind of work where you can figure out what it is before it’s been made.” He’s said of the series that he wanted to get a ‘chakra’ response to the work, a sense, he says, of spiritual connection, but he doesn’t elaborate here. “Oh, that’s good if you can,” is all he says. But he’s obviously imbibed some of Emerson’s Transcendental philosophy, albeit perhaps using a language that contemporary Americans can more readily get with.

“I’m not interested in the kind of work where you can figure out what it is before it’s been made”

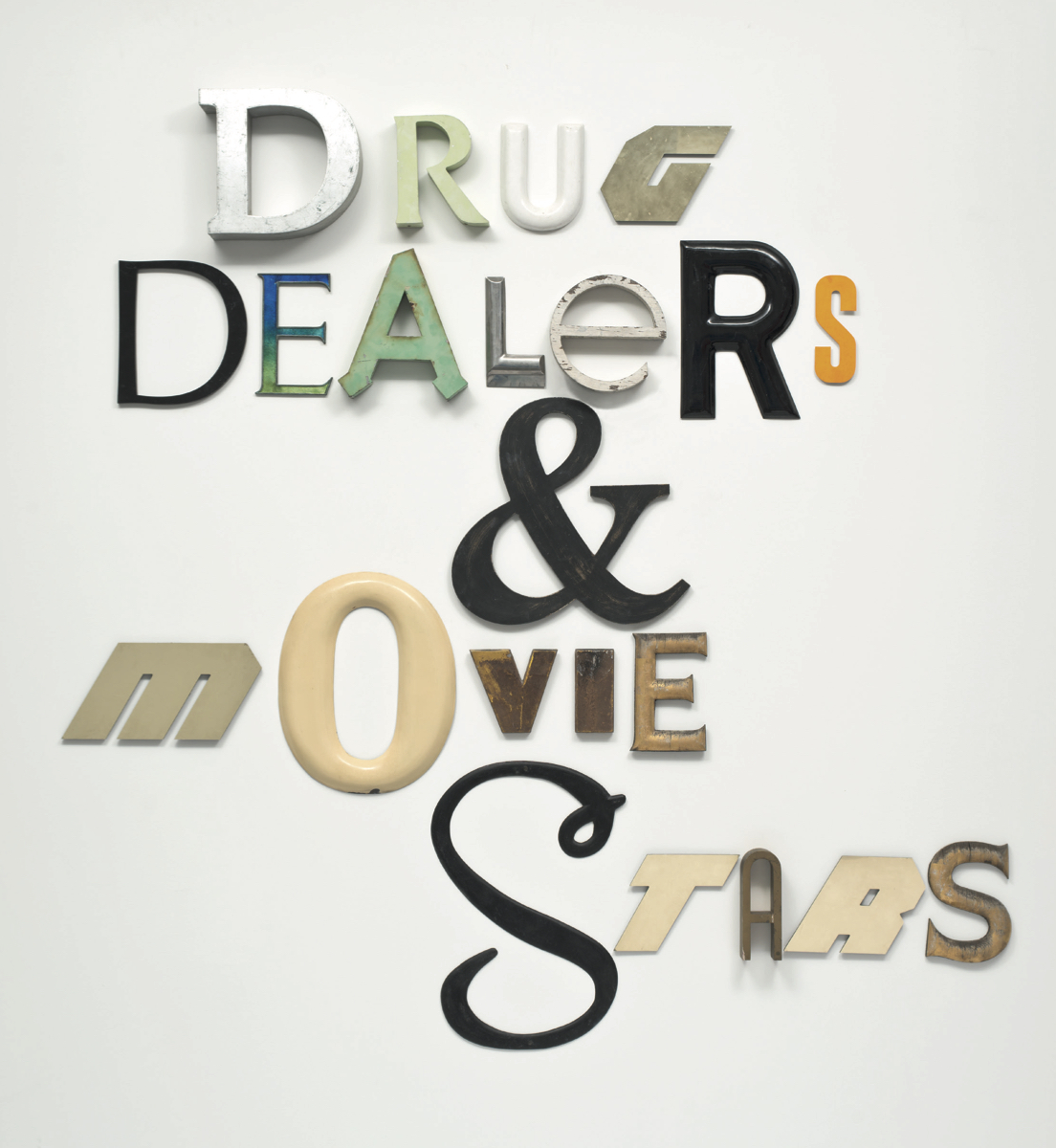

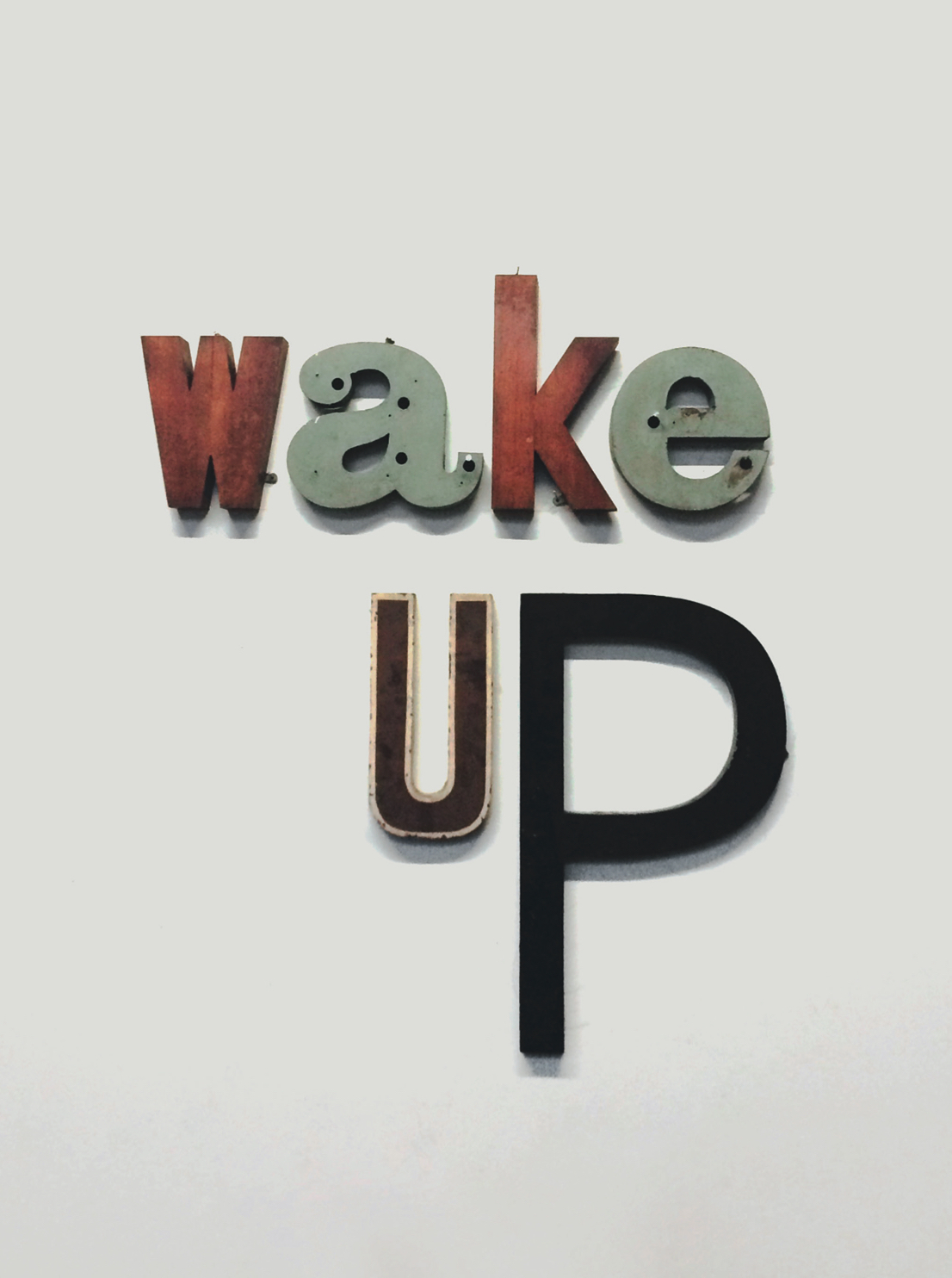

Pierson is better known for his theatrical signage works than for his paintings. These are huge three-dimensional letters that come in all sorts of fancy fonts and bring to mind aspects of Americana. With their intriguing sculptural arrangements, they spell out single words or slogans: “Drugs,’ ‘Angst’, ‘The One and Only’, ‘Heaven’, ‘Silence,’ ‘Movie Star’, ‘Desire Despair’, ‘Drug Dealers & Movie Stars’. There’s wry humour, but also a seductive sense of faded glamour, a hint of a vaudevillian entertainment industry long defunct. Most critics have noted the sense of nostalgia, of yearning and loss in his work. He began making the word sculptures back in the early nineties, often using mismatched letters salvaged from junkyards, old movie theatres, roadside diners and Las Vegas casinos. They are among his most striking, evocative works, and it’s a series he continues today.

Looking across the broad range of his output—and he’s nothing if not eclectic— there’s often a strong connection to American cultural history. But he won’t dwell too deeply on the nature of this preoccupation. “I guess, past 50 [Pierson is now 56], I realize that more and more I’m a product of my environment and an American, and it would be great if I had some, you know, kind of European panache, but I don’t.”

“‘…it would be great if I had some, you know, kind of European panache, but I don’t..'”

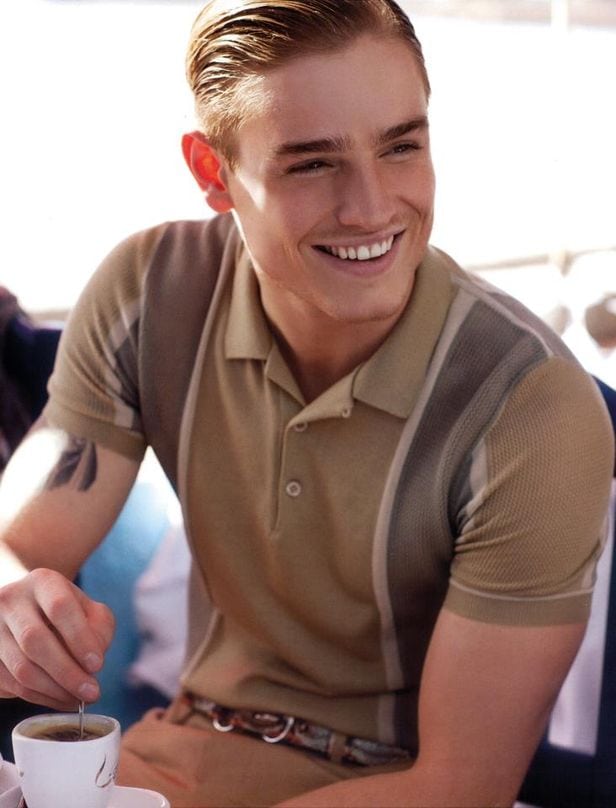

Pierson is also a photographer, and has had a hugely successful commercial career in which his lens has probed the smoothly photogenic beauties of the likes of Brad Pitt and Naomi Campell. In 2003, he produced a book of photographs simply called Self-Portraits, though the images were actually of unidentified men, across a broad age range. The series exuded an inescapable homoeroticism, and perhaps these intimate shots were a portrayal of Pierson’s own desire. The photographs have the casual look of snapshots, an aesthetic that had become prevalent by the nineties (Pierson is now an avid user of Instagram, a perfect medium for his casual point-and-snap aesthetic). Why did he call the series Self-Portraits?

“Well, it was a little bit glib, and I was having fun with it. I’d never worked on a photographic series before, so I was never like, “Ooh, I’m working on a series, and here’s my series of the cemeteries of Eastern Europe.” The title of it actually came after the work. I was kind of making fun of the photographic series. I mean, I put it in a very fancy book and I had a very scholarly essay to go with it, and, when they were in the gallery they were framed quite majestically. Before that I had always had a very, you know, pinned-to-the-wall aesthetic.”

So how does the glamorous commercial work into Pierson’s activities as, for want of a better term, a fine-art photographer? He says it doesn’t overlap, but he admits that the commercial work allows him “another fantasy of glamour” to enjoy. “And suddenly you’re thrust into a world where you’re making things happen on the spot and solving problems with other people around you. And once in a while, just once in a while, I get a great picture for myself.”

I tell him that he’s one of the few contemporary artists I know where you can’t really date his work too accurately, or tell whether they’re made by the same hand—from those tiny watercolours which weren’t anticipated by anything he’d done before, to the signage works, with their hot, lush Pop aesthetic, to those cool, almost off-hand photographs. ‘I like that,’ he says. “Well, it creates a joy for me to make something that looks like it was made from days gone by.”

I ask what he’s doing next—is he thinking of ploughing further fresh fields? Any new departures? “That’s a good question,” he says, slowly. “Well, I’m desperately looking for ideas. Got any? Ok, I’m trying to figure out a way to approach photography that means I can make it look a little modern and not modern. I should have been figuring out digital photography these last ten years. How to make it work for me. I need to figure out a way to make it seem modern—edgy and cool. So, I’m going to spend time trying to figure that out.”