Fashion is generally embodied in three definitions: fashion as an action, fashion as a time and fashion as a system, an industry. In its discourse, we often refer to the fashion industry, but when considering it as a cultural point of review, it engages with all definitions and can serve as a mirror to the socio-economic and political footprint of a time period. It is a lived-in version of culture.

Hendrickje Schimmel, known as ‘Tenant of Culture’, is a Dutch artist working out of the fashion capital of London. Her practice combines fashion objects and making techniques with sculpture to create enigmatic works of demi-couture that hint at the existence of a fashion object which can be adorned in its materiality but often serves to create a wider discourse around the convoluted history and production of fashion garments.

LUCY BROOME: What inspired the title ‘Tenant of Culture?’ Would you describe it as a title, name or alter ego?

TENANT OF CULTURE: It’s a combination of those things. I came up with the name when I just graduated to situate myself in between fashion and art, referring to the tradition of the fashion label. It’s a play on the idea of the fashion house, the Maison, a term that is associated with quality, luxury, tradition and ownership. “Tenant” refers to the opposite of that: the notion of renting within these structures rather than owning them. It also comes from the writing of Michel de Certeau. He uses the notion of the Tenant as an allegory for an (unintended) collaboration between producers and consumers to question the hierarchy of who produces and who consumes. Subverting the idea that consumption is always a passive practice and production is an active practice. He refers to the processes of production that exist within consumption, which relates to the recycling and re-interpretation of mass-produced objects.

Tenant’s show ‘Ladder‘ is currently on display at the Soft Opening gallery in Cambridge Heath and is described as examining the ‘perceived dichotomy between destruction and decoration, interrogating how the aesthetic taste has, for centuries, been appropriated within the fashion industry.’ The title ‘Ladder‘ conjures semantics of movement and progression, or perhaps in the case of the cyclical nature of the fashion system regression and the destruction and the rips and tears of literal ladders in nylon fabric. By this, Tenant is referring to the literal trend for distressing garments that exists often in high fashion (think Balenciaga).

Over time, fashion’s flirtation with the aesthetics of destruction has become increasingly pronounced. Caroline Evans in Fashion at the Edge is referenced in an accompanying pamphlet to the show written by Eilidh Duffy and entitled Modes of Destruction, History Unravels Before Us, Loose Screws and Broken Machines, Stitching and Slashing, Expressing the Times. In Fashion at the Edge, Evans presents the idea that a subset of avant-garde designers working at the turn of the last millennium (known as the 90s anti-fashion designers) adopted the aesthetics of destruction and decay as a cultural response to the horror of the 20th century.

In ‘Sabotage in Acrylic‘ 2023, Tenant produces large pieces of machine-knitted yarn that have intentional marks of distress or are indeed sabotaged. Sabotage here has multiple insinuations. Firstly, the fact that it derives from the French word saboteur, originally used to refer to labour disputes in which 19th-century textile workers, often referred to as ‘Luddites’ who wore wooden ‘sabots’ interrupted production through multiple means, one being through the destruction of fabrication machines. Simultaneously, it references the work of well-known anti-fashion designer Rei Kawakubo for Comme Des Garçon in the late 1980s, who intentionally sabotaged large knit machines to create gaping holes.

LB: Your work draws a lot of parallels between the process of modernity and the modern day. The Luddites were protesting the age of mechanical production, as in machines replacing people. It’s interesting because you could say there is a similar phenomenon happening with AI technologies, like in the case of the Hollywood strikes. People are once again having technology-induced anxiety, similar to what has occurred throughout history. But on the other side of things, you have people working in the fast fashion circuit whose labour is absolutely not being replaced by machines and are having the opposite problem.

TC: In Eilidh’s text, she references today’s geopolitical anxieties and the 90s, when this similar fashion of destructive clothing occurred. Fashion is such an opaque industry, so it’s difficult to get a holistic vision of what the industry is because it only allows you to see it in fragments. That’s also its strategy to create a very fragmented, disintegrated, and globally outsourced industry. There’s so much information you cannot access or industrial problems that are just too big to comprehend or comment upon in an artistic practice. I try to get access to those things and research them so I can uncover links or points of tension to look closely at and create a more embodied understanding of the material processes of fashion production.

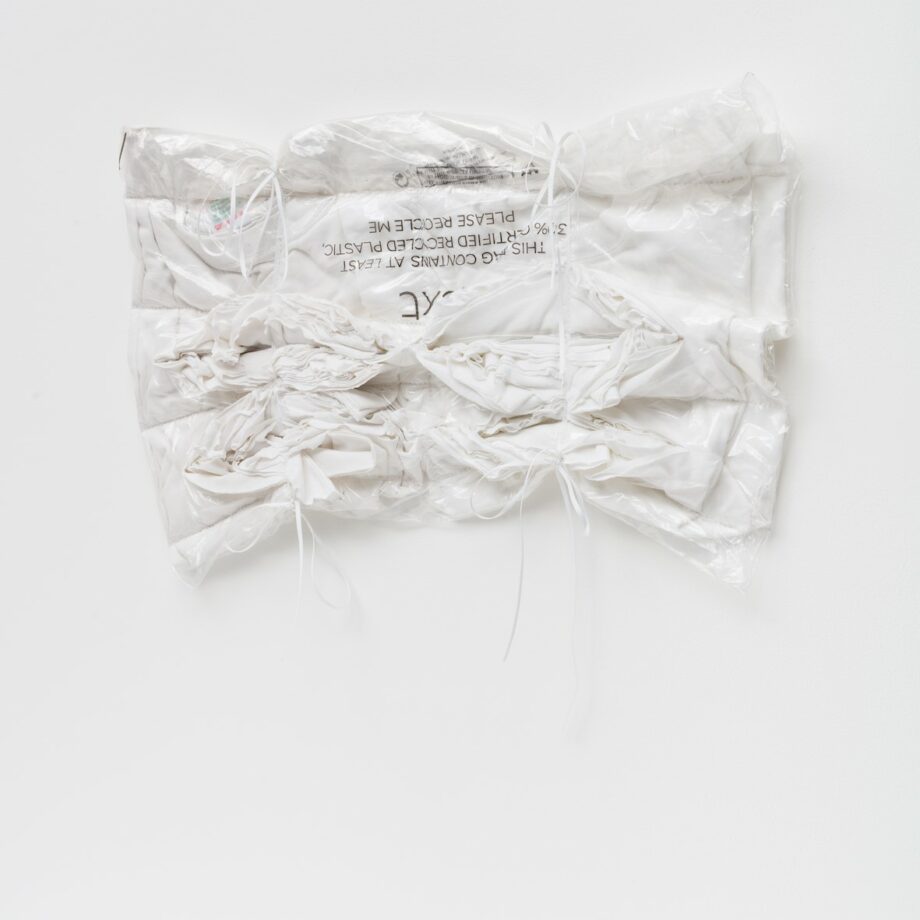

In the Haul, 2023 series, Tenant acquires plastic garment bags, some with logos of fast fashion producers such as Shein visible, and slashes them open. This is not only in reference to the well-known practice within fashion of slashing unsold garments to remove them of their value instead of recycling them, but it also has a more obscure historicism.

TC: All the works look for a process of a disastrous deathly event that is then aestheticised […] The Haul series, for example, is inspired by 18th-century or European Renaissance fashion of sliced textiles. Sleeves were meticulously sliced, and the undergarments beneath were pulled out. It’s a familiar sight from paintings at that time. I was always quite fascinated by that very handmade craft-based technique, but it is simultaneously just slicing into fabric. I started doing some research into the origins of that and found it came from a 15th-century Swiss Mercenary army, who were very skilled soldiers for hire essentially. They were romanticised as these young men who were extremely violent and strong and won every war that they were in. Because of this, they were exempt from sumptuary laws, so they could wear brighter colours and silks, which peasants in those days weren’t allowed. Their costumes are very fashionable in a sense, and they would return from battle with those garments slashed up and the silk lining piling out. They were heralded as heroes, and consequently, the European elite started adopting those fashions into their garments.

Time is an innate and inseparable quality of fashion. By activating a work historically, it places it in conversation with its cannon —but not necessarily in the cannon of linear time. Because of Western fashion’s cyclical nature, whose trend cycles at one point operated on repeating itself every twenty years, a scale of which is now questionable given the acceleration of trends, the initial form of fashion is already non-linear. So, when assessing through a historical approach, it is functional to engage in what Caroline Evans calls ‘Uchronic time.’ Ucronia is derived from the word utopia and describes a ‘non-place’ or ‘non-time.’ Roland Barthes, the main point of inspiration for Evan’s theory, writes on fashion that “Long-term memory is thus abolished, time reduced to the couple what is driven out and what is inaugurated pure fashion, logical fashion is never anything but an amnesiac substitution of the present for the past” “In fact, Fashion postulates a diachrony, a time which does not exist: here the past is shameful and the present constantly ‘eaten up’ by the fashion being heralded.

By interweaving literally and figuratively the current fashion industrial labour complex with its transient configurations via mediums of translucent fabrics or disintegrable material substances written into the canon of history, Tenant of Culture, in contrast to their name, narrates a space at Soft Opening that they are in utter control of, surpassing the occupation of Tenant, and perhaps more aptly is a purveyor of culture.

LB: Do you think in order to create, you also have to destroy?

TC: Within the industrial system of fashion, garments always exist in between creation and

destruction. It’s a system that is based on the rules of the ephemeral and the valorisation of the

temporary. Creation is as important as destruction in this system because of psychological

obsolescence. This temporality is essentially the meaning of the word fashion. That’s why I find

it interesting to talk about destruction within the fashion system because it is a key strategy for

the functioning of the industry.

Words by Lucy Broome