Living against our skin for centuries, bearing witness to different times, cultures, and modernities, fashion lives with us, and it is an inescapable witness and essential anthropology. In a new column for Elephant magazine, Lucy Broome unpicks the epoch of fashion, exploring its diverse interchange with politics, arts and culture to reveal how fashion is both a mirror of our times, indeed at the very edge of aesthetic and material communication.

How does fashion and philosophy relate? Philosophy, the study of knowledge relative to existence, is often seen in stark opposition to the excessive material narratives of fashion, which are frequently deemed surface-level. Yet, can both intersect when considering their relevance to cultural and social phenomena?

Human history has a long-standing relationship with carnal fascination, whether that is taking a bit too keen interest in Freud or being inexplicably obsessed with a new pair of shoes. Both place the body in a wedge between the physical phenomenon of self-presentation and external perception. A close reading of Freud might lead to an existential crisis about perception, sexuality, and familial relations. Similarly, wearing a 2012 pair of Isabel Marant wedge-trainer heels in 2024 will receive mixed glances in the street and an uncouth comment from a family member. Clearly, they weren’t paying attention when reading The Interpretation of Dreams.

For this edition of Fashion and the Edge, the historical preconceptions that may have, at another time, been communicated by the Surrealists, who looked to Freud, who looked to Plato, which are hidden within the material narrative of fashion, will be uncovered. For instance, when a critique of the ‘perversive nature’ of female bodily hair is fashioned into a dress and placed atop a hairless celebrity, it suggests something else entirely —think Kendal Jenner wearing the recent Artisanal Maison Margiela dress. This piece explores how fashion’s relationship with the carnal reflects the art historical canon, displaying how an individual manipulation of the feminine image across time allows them to fashion society’s perception of them as a genius.

In 2023, Caroline Evan’s seminal text Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Death, 2003, received a new edition twenty years after its original release. The book itself reflects on a specific timeframe of fashion, the 1990s, which Evans felt was a time that reflected the cultural feelings of death, trauma, alienation and decay.

“We speak of ‘edgy’ fashion to suggest sharp, urban, knowing, experimental, unsentimental fashion. We are at the edge of centuries and on the edge of technological transformation. Such epochal change requires its participants to embrace a knowledge economy, to turn their backs on the old age of modernity and begin to make sense of the revolution in the communication of the last thirty years.”

Caroline Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Death, 2003.

In many ways, fashion at the turn of the century is having its revival in 2024. It started with the growth in the popular canon of edgy 90s anti-fashion, or the ‘archival,’ embodied in an aesthetic pioneered by the members of the infamous Antwerp Six, including Ann Demeulemeester, Dries Van Noten and Walter Van Beirendonck —but not Martin Margiela who is often mistaken for being a member. Moreover, in the late nineties and early 2000s, Evans saw the narrative shift towards some of the fashion histories of most celebrity designers. Celebrity, in that their characters surpassed just their names on a label, becoming caught in the public eye in all capacities of their lives —for better or worse. Designers such as John Galliano and Alexander McQueen have a significant focus in her book. It is arguable that in the zeitgeist 90s fashion, or more, its semiotics and cultural relevance are experiencing a revival, reflective of our politics and time. As Evans witnessed, fashion is a cultural vanguard, an epoch that can act out what is hidden culturally. Her original work saw fashion pushed to its borders, or rather saw that fashion was itself pushing the boundaries of contemporary society. Then now, in its revival or reincarnation, does it stare into the abyss instead?

Courtesy of Maison Margiela

Courtesy of Maison Margiela

The fashion world was recently besotted with the latest Galliano for Margiela show, so dynamic, sensual and effective in transporting the onlooker to a uchronic nineteenth-century Paris, you felt you might contract syphilis just at a glance. Some thought it was verging on more Galliano than Margiela given the theatrics and proportions, which, whilst not untrue, might make an individual look over the reference points, which were from the geneses of Margiela’s own. The mode of a journey into the dark underbelly of nineteenth-century Paris was far more of a Gallianoism, given his panache for history shown in his 1984 Central Saint Martin’s graduate collection Les Incroyables (the Incredible Ones), a French aristocratic subculture of the eighteenth-century. However, Margiela similarly drew from history, specifically the twentieth-century Surrealists. The Surrealists, including Marcel Duchamp, Mimi Parent, André Breton, Meret Oppenheim and Savlor Dali, exhibited an influential series of exhibitions between 1938 and 1965 in Paris, which Alyce Mahon has described as “ultra-uterine.” Stemming from the Freudian exploration of the unconscious, particularly the link between the dream and repressed desire, Margiela’s work references the recurring surrealist motifs. One such motif was the mannequin, which Margiela is famous for deconstructing in his Semi-couture ensembles, which would take from the body of linen tailoring dummies, also known as the ‘Stockman bust’ used by Parisian haute couture ateliers and transform them into deconstructed garments.

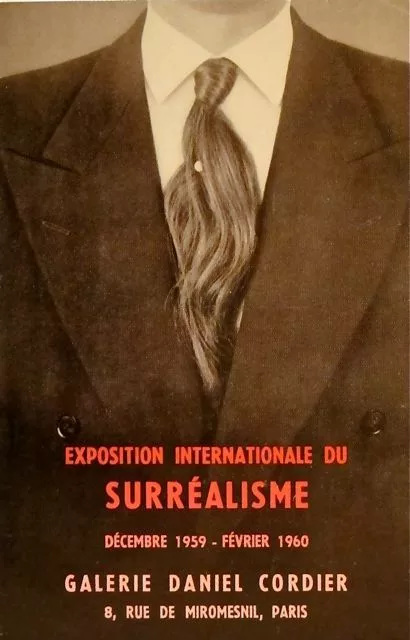

The 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme showed an ‘Allée des Mannequins’ also referred to as The Most Beautiful Streets of Paris, that alluded to the history of prostitution in Paris, which Galliano was also referencing and included mannequins from artists such as Duchamp and Dali, with brothel water dripping down on guests for added effect. On André Masson’s Mannequin, in the place of the vulva, is an arrangement of circles that looked like eyeballs placed around a mirror, with two curly plumes rising from the top. In much of the male Surrealists’ work, the female body was used as a site of uncanniness, symbolically objectified to reference the feminine as an unmanageable or uncontainable terrain. That ultimately depicted the female body, more specifically, the prostitute’s body, as a threat. When translated into the work of some female Surrealists such as Mimi Parent or Meret Oppenheim, this transgresses into a critique, particularly that of the fear of female bodily or pubic hair. Fashion and Cultural historian Anneke Smelik writes in ‘The Danger of Hair,’ 2007, that when human hair is abstracted from the head, it becomes a gruesome object because “they no longer belong to the living body, but have become dead material.” Mimi Parent uses bodily hair, abstracted from the body and re-contextualised, as seen in her works Masculin-féminin 1959. Masculin-féminin was fashioned from Parent’s own hair, which acts as the tie for a man’s tailored suit, parodying bourgeois dress codes and enticing the erotic potential of female hair and masculine carnal infatuation for something that is simultaneously gruesome yet carnally desirable. In Margiela’s work, hair is famously a recurring motif, epitomised in his wig jacket, which first appeared in the Fall Winter 2005 Artisanal line, playing on the use of feathers in couture by replacing it with imitation human hair. Fast forward to Galliano’s Spring 2024 couture collection for Maison Margiela, and there is a direct link to pubic hair and the Masion’s application over the years. Underneath the ghostly layers of tulle and synched waists were hand-sewn pubic merkins. The merkins varied in their visibility, but when clear, added to the accentuated proportions of the models via creating an angular landing strip (aka the French bikini wax), embracing the sensual and carnality which is innate to clothing, being the closest thing to our body and skin, living with us as a conduit between us and the outside world, while recording our memories, albeit erotic or banal.

Courtesy of Granary One.

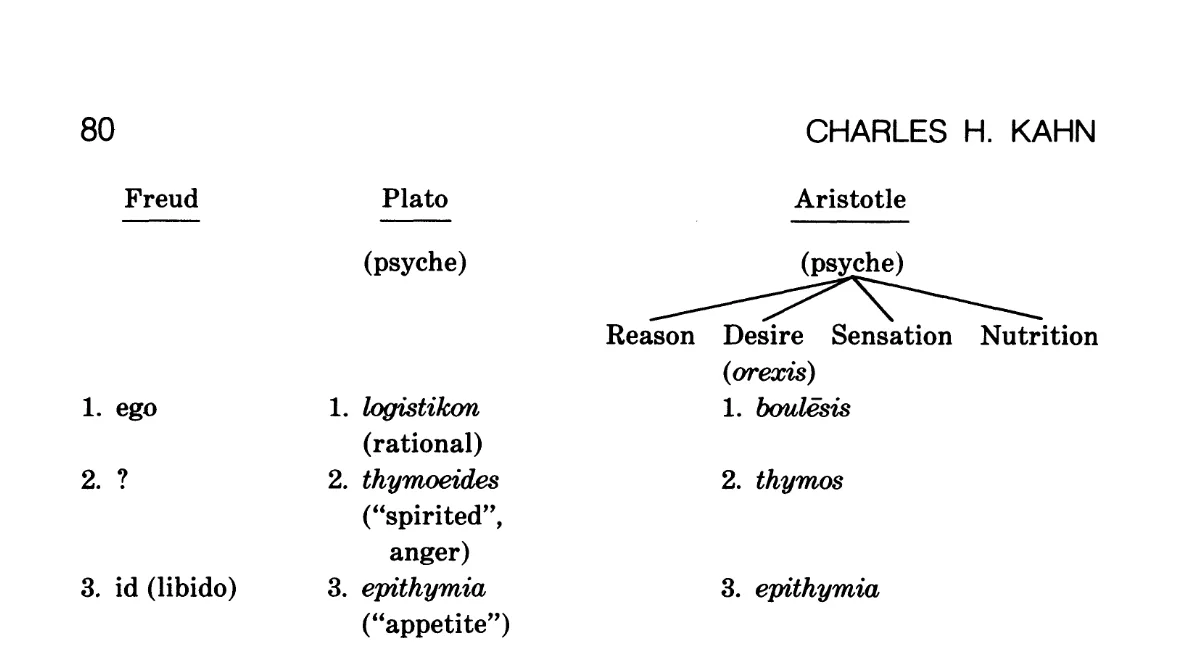

There’s a sultry sleaze that we left in the 90s that fashion wants back —a raw raunchiness and a desire for an authenticity lost through hyper-digitisation, which continues to fetishise decay, that was a particularly prominent feature in the works of McQueen and his contemporary Galliano. Clothing innately serves as a fortuitous reminder of its impermanence, and so our own, existing as the ultimate manifestation of the interchange between the projected desires of our society and our own internalised desires. In the Western context, the conceptualisation of desire partially stems from Plato’s study of the psyche, where he presented the notion of eros, a universal desire for the beautiful, which is characterised by what is good. The second exhibition of the Surrealists was entitled EROs (Exposition InteRnatiOnale du Surrealisme), and in Andrē Breton’s introductory essay he writes that eroticism was the ‘highest common factor’ in surrealist art since its inception, and so equating eros with carnality. In Plato’s Republic, Diotima interprets eros as a desire to possess good things and pursue the beautiful through procreation. Charles H. Khan writes that “The characterisation of eros as the desire for procreation in beauty serves precisely to link the carnal lover to the metaphysical lover as participants in the pursuit of a common goal.”

When considering it in line with what Evans saw, arguably, carnality within fashion is a projection of our collective anxieties that manifests as a desire to possess the beautiful via its vicarious consumption. Galliano and McQueen are famed not only for their creations that signified their genius but also for the controversial nature of their characters, in which Galliano remains particularly divisive. The two were the main subject of Dana Thomas’ 2015 book Gods and Kings, with McQueen receiving a documentary highlighting the more tragic aspects of his life and death, ‘McQueen’ (2018). In March, MUBI has released a Galliano documentary, ‘High and Low: John Galliano’ which will enter the dichotomy of his life as a disgraced [question mark] artist. Posing the question to the individual whether this is still the case, whilst making us both judge and jury whether the case of the ‘genius’ relieves artists of their wrongdoings? For context, in 2011, Galliano was fired from his position at Dior for an antisemitic rant that occurred at a bar in Paris. Not an isolated incident, Galliano was known for making various antisemitic and racially charged comments, with this being the tipping point, soon after being brought to trial in France and fined. McQueen and Galliano were the golden children of LVMH in the early 2000s. It appears that this success also pushed them both to the very edge, epitomised in their drug-fuelled binges and vicious outbursts which led in the end to McQueen taking his own life.

A mark of genius in each appears to be how they appear to present the ultimate presentation of the female form, appealing to our collective ideal of eros and the masculine genius archetype of being the creator of such an image. Fourteen years on from the tragedy of McQueen’s loss, Kanye West is seen wearing an infamous masquerade mask with a white crucifix affixed to it, from McQueen’s Autumn/Winter 1996 collection Dante. West himself is experiencing a similar high and low, that also spurred from his antisemitic comments, among other racial and politically questionable statements. It’s no secret that West is experiencing his own mental health crisis, which often is disseminated by videos of himself detailing the ins and outs of it. Society becomes divided by these questions, but the overarching feeling is that because of the cultural weight of these artists, their continued work is continually perceived as “uncancellable,” whether we are infatuated by the carnal designs of Galliano and McQueen or the equal emphasis on the female form that takes place in West’s music and visual presentation. From Plato writing on desire and Kahn saw that “Diotma’s account of the lover’s ascent [implying] that it is a single desire that begins by taking beautiful bodies as it’s object and ends with the beatific vision of the form,” to the male surrealists as seen by Katherine Conley, aligning themselves with the feminine from the outset —carnality is a vehicle for genius.

In genius, we want celebrity; in genius, we want spectacle. Mass disseminated suffering creates a great story, a narrative that suits society’s death drive and its need for individualism. History continues to be a circle and fashion a mirror. The grotesque speech of individuals must always be read as a projection, a projection of archetypes conjured from the cultural egregore. The individual must always reconcile that what lives in another, to an extent, lives within themselves. Without that reconciliation process, history is bound to repeat itself, and scapegoats and archetypes continue to simply fluctuate in form. Still, history is forever enacted through the simple act of getting dressed.

Written by Lucy Broome