Soon after I crossed the threshold of the Grand Palais it hit me: this year’s edition of FIAC is devoted to hell. It makes sense, given today’s political and climatic turmoils; we are “Placed within the context of an implosion” (words written on the wall near the information desk near the entrance). As art history tells us, depictions of the abyss have always been as popular as heavenly scenes.

Kamel Mennour, London at FIAC 2017 © Marc Domage

Galerie Perrotin sets the tone with Takashi Murakami’s five-metre tall Flame of Desire. This imposing sculpture features a gold-plated skull engulfed in flames. From burning heat to freezing, Ricci Albenda’s Cold Day in Hell sits nearby. There’s a ghoulish interest in flesh at Pietro Sparta Gallery, in a mock medical prescription for an amputated lobe, à la Vincent Van Gogh. Sickness is referenced elsewhere too, as White Cube showcases Damien Hirst’s Lies, Lies (2008), a smaller pharmacy than his original room-sized installation (1992). Death mostly manifests in the guise of skulls, notably in Urs Fischer’s aluminum panel Chronical and Roe Ethridge’s Louis on Brass #3, both at Gagosian, and in Yan Pei-Ming’s Déjeuner Sur L’herbea—a grisaille after Edouard Manet’s impressionist masterpiece—at Thaddaeus Ropac.

This year, a palette of black and white prevails at FIAC too, reflecting this mood. A series of melancholic drawings by David Hockney stands out at Lelong & Co. At Gladstone Gallery, Camille Claudel’s features are so thick under Elizabeth Peyton’s brush that she is barely recognizable. Right next to this portrait hangs a frighteningly dark landscape by Francis Picabia. One of Perrotin’s works on show is Sophie Calle’s Le Fantôme de Souris, literally Souris’s Ghost (“souris” is French for mouse, and is the name of the black and white cat in the picture).

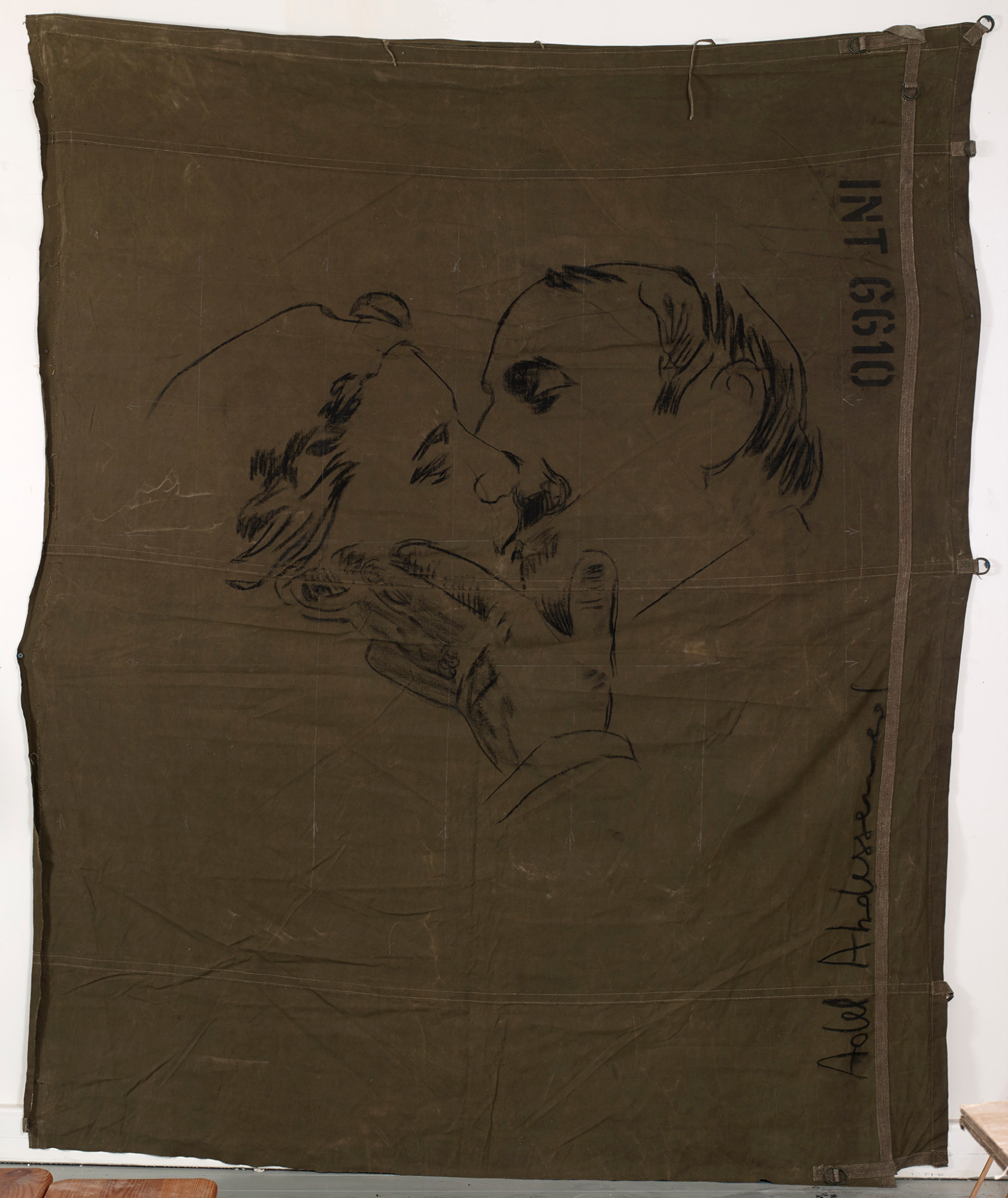

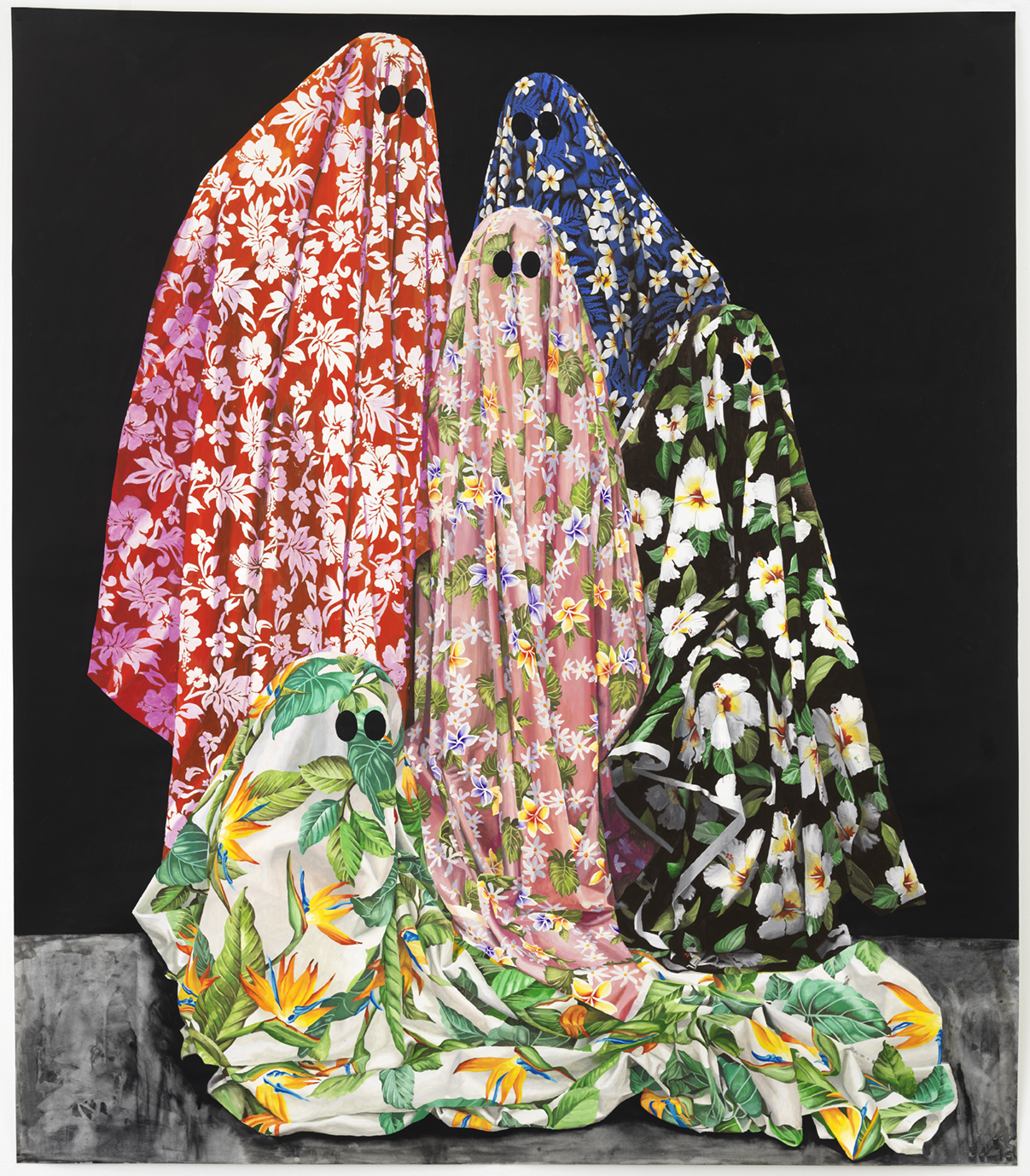

This feline rodent—unless the metamorphosis went the other way around—foreshadows the apparition of various creatures throughout the fair. One of Ugo Rondinone’s well-known Moonrises stands in Kamel Mennour’s perimeter. The twelve pieces of this series are said to be the artist’s first figurative sculptures, except that it is hard to tell what those monumental contorted visages exactly represent. Grinning dinosaurs? Some kind of extraterrestrial worms, as the title would suggest it? While Dvir Gallery is populated with Adel Abdessemed’s stone-sketched phantoms, Gilles Barbier’s Hawaiian Ghosts #9 haunt Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois gallery’s spaces, covered in multicoloured textile coverings. Next to this satirical photograph, Niki de Saint Phalle’s reclining Nana (Lili ou Tony) conveys despair. The wriggling fetus-looking statue at Galerie Krinzinger is one of the most truly blood-curdling pieces in the fair—Tony Cragg’s womb-like onyx sculpture Sail at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac would be the perfect nest for it.

Escape feels impossible in this space. “Not Here” informs Rémy Zaugg’s sign on Mai 36 Galerie’s frontage. “There There There” echoes one of Paula Cooper’s partitions—a message from Robert Wilson. Every turn apparently leads to a dead-end. After hitting a purple wall at Eva Presenhuber gallery, I reach a brick one at Anton Kern.

Chaos is all around. Various utensils, among them gloomy brooms, plastic bottles and boxes, are stacked up at the centre of Blum & Poe gallery’s booth. Galleria Massimo is home to a cracked glass cupboard by Ariel Schlesinger. Mircea Cantor’s Vertical Aleppo at Magazzino consists of a green column planted on in pile of rubble, as though it’s the sole survivor of an unpredictable earthquake. Everything and everyone is broken. Even Ugo Rondinone’s wax-molded nudes—the only three pieces Sadie Coles gallery have chosen to present—are sitting on the floor with a depressed expression and lethargic posture.

This penchant for destruction and affliction is literally set in stone, which happens to be the dominant material in the galleries this year. Many sculptures have the appearance of rough rocks, lying directly on the ground: Konrad Fischer presents Reborn as a Stone by Thomas Schütte, a ceramic which, given its spherical shape and the three holes corresponding to the eyes and mouth of a human face, could easily pass for a bowling ball.

In the end, it’s left to the modern art at FIAC to lift the gloomy spirits. Ironically, Andy Warhol’s Shadows have never looked more luminous than at Gagosian’s booth. Marcia Hafif’s pastel monochromes have the same soothing effect. Harmony thrives at Galerie Thomas Zander, and it must boast at least fifty shades of grey.