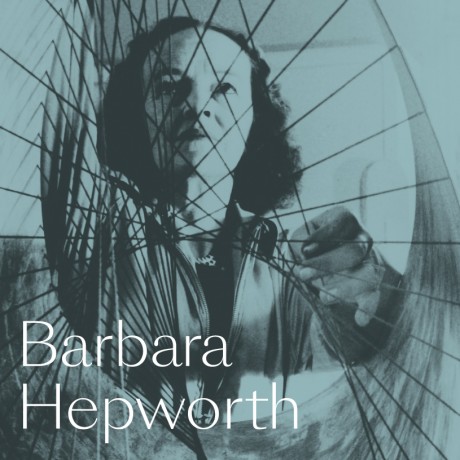

“It might be possible to mistake the huge-browed Miss Hepworth for a professional intellectual,” said a 1955 Sunday Times review. “But she is, in fact, the mother of four children.” Barbara Hepworth (who died in 1975, aged 72) would perhaps be relieved that arts coverage isn’t quite as openly sexist anymore. She would be less pleased that a covertly gendered idea still persists about her work, pigeon-holing it as “nice” (even “cosy”) no matter how monumental it gets.

A new study, Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life by Eleanor Clayton, shows the disagreements Hepworth had with curators and committees who made her work appear “ladylike” through a muted presentation. It led critics to see her work as sleek, smooth and professional, when it was actually “force”, “spice” and movement that Hepworth wanted to foreground.

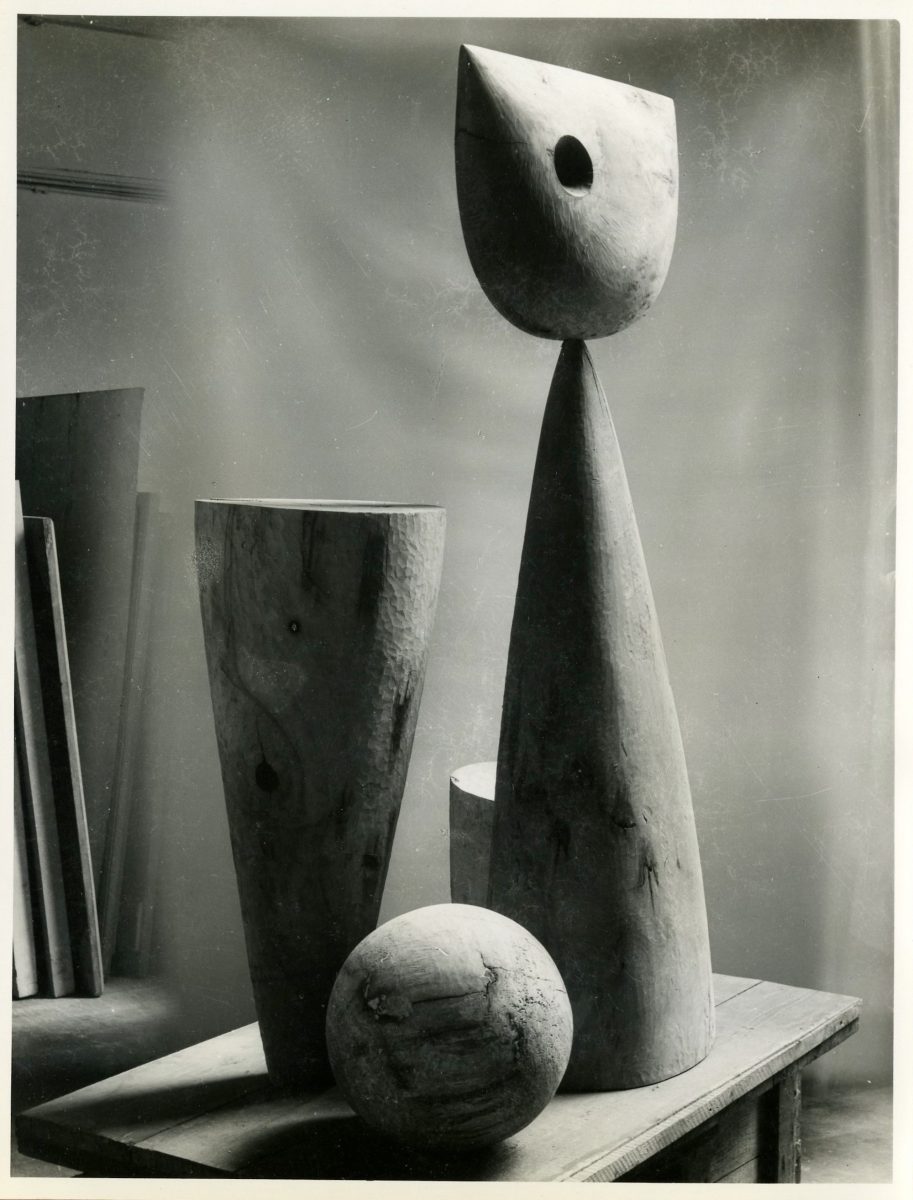

It feels as if time itself worked on her best sculptures, rather than an artist. If there is a smoothness to many of Hepworth’s “closed form” sculptures, it is geological or oceanic forces that seem to have shaped them. Her surfaces and the flow of her sculpting is, in the origin myths, chalked up to driving over Yorkshire landscapes with her father. It would take years, though, before the idea of representing this direct purity in abstraction was unlocked.

“It feels as if time itself worked on her best sculptures, rather than an artist”

In 1920 she joined Leeds School of Art, then won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London. Travelling to Italy on another scholarship she added light to her spectrum of aesthetic effects and needs (“something lacking in my childhood in Yorkshire”) and married John Skeaping, the sculptor who beat her to the Prix de Rome. They began exhibiting their work as a couple, impressing critics and collectors for being “carvers, not modellers”, rather than passing on their ideas in clay to be executed by a master craftsperson. It remained her method until she started modelling for bronzes cast from the mid 1950s onwards. In 1931, Hepworth met Ben Nicholson, another modern artist she would love, be inspired by and then surpass. She divorced Skeaping the same year.

Clayton, who is a curator at The Hepworth Wakefield, addresses a biographical criticism of Hepworth that pairs counterintuitively with the earlier “feminine” criticism of her work, namely that she wasn’t maternal because she didn’t give up her career for her children. Roger Berthoud wrote in The Independent just a decade ago: “It was a cruel stroke of fate that made this unmaternal, work-obsessed woman bear triplets.”

Clayton reframes Hepworth’s experience of motherhood. She cites this 1929 quote: “My son Paul was born and, with him in his cot, or on a rug at my feet, my carving developed and strengthened”. She also highlights a similar comment Hepworth made about her triplets with Nicholson: “When I started carving again, my work seemed to have changed direction although the only fresh influence had been the arrival of the children.” It was at this time that Hepworth started producing group sculptures made of two or more abstract forms. “You will see how all the forms flew quickly into their right places in the first carving I did after [they] were born,” she commented.

Hepworth has faced censure for entrusting her triplets to full-time nursery care for the first years of their life, but Clayton offers telling background. Twelve weeks after the birth Nicholson returned to Paris to work and be close to his other family with his wife the painter Winifred Nicholson. Living in a damp flat that had gas leaks and broken windows, Hepworth was unable to both look after and financially support the triplets, so was medically advised that they be cared for in a nursery.

“Reading about prolific artists can feel like a rebuke. Reading about Hepworth’s huge output is infectious”

The decision came with a heavy heart: “Logic says put the babies in Wellgarth for a year […] Another part of me says struggle on—I don’t know which part of me it is maybe the sentimental part.” Hepworth visited them regularly and they were back in her full-time care (much of which was sole) almost as soon as they ceased to be babies. It feels reductive to focus on such a non-story, but Clayton’s book has been pushed into a corner by the persistence of this legend.

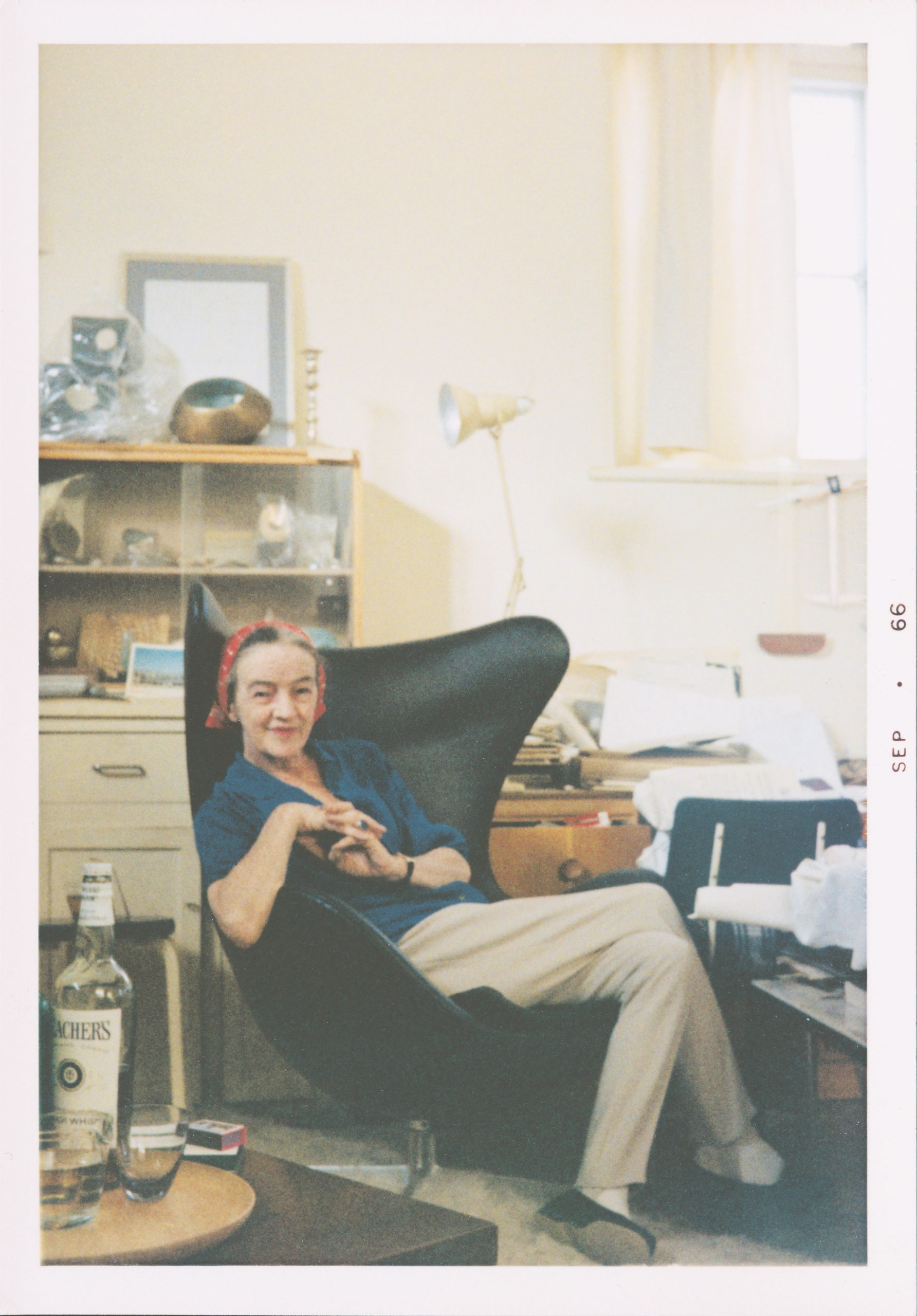

Reading about prolific artists can feel like a rebuke. Reading about Hepworth’s huge output is infectious. She is quoted, upon seeing a new space or piece of material, as saying it gave her 20 new ideas. She immediately gets started on them, often concurrently.

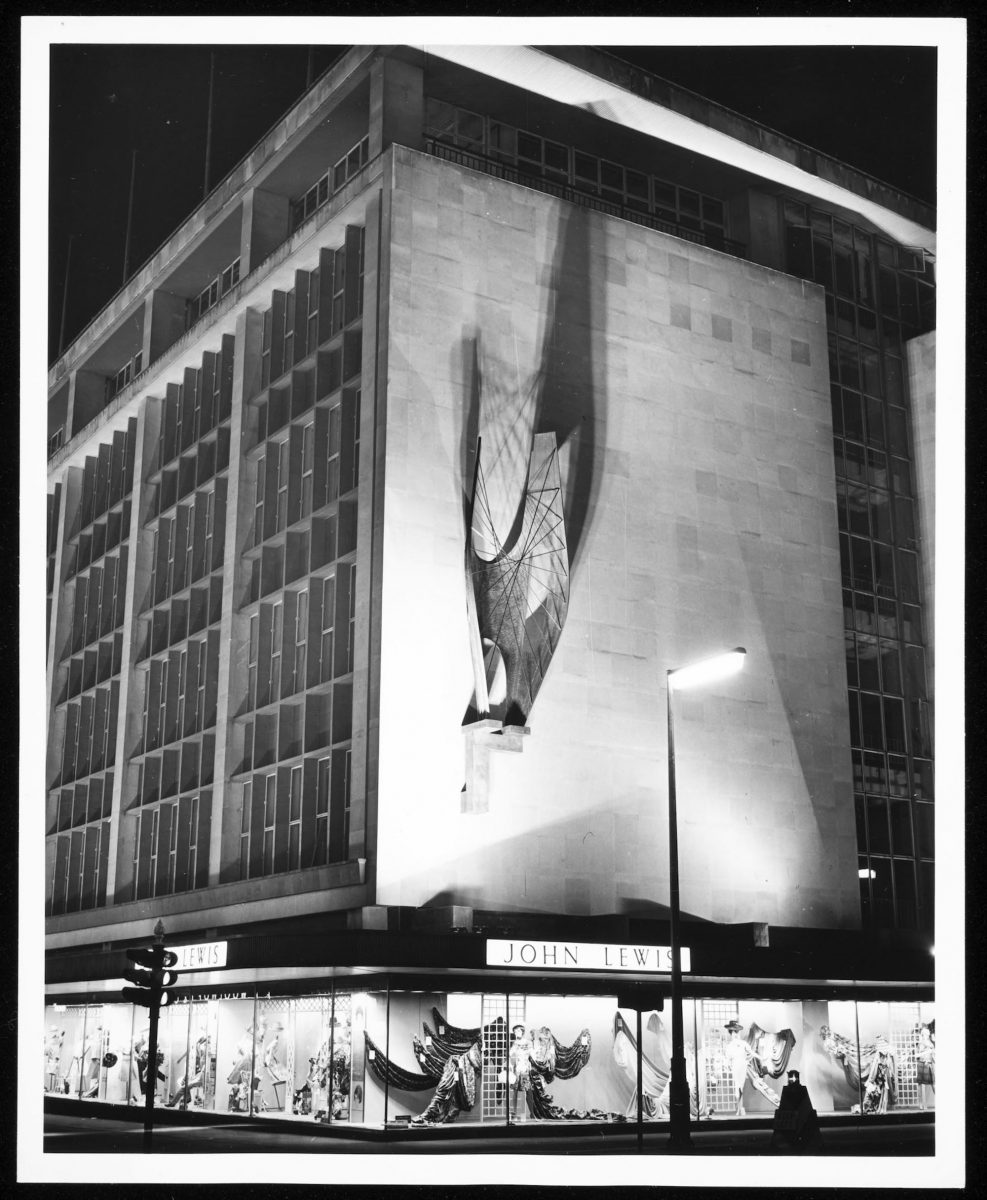

Clayton stresses the urgency of Hepworth’s ever-growing desire to work. In the 1960s, she suggests, the sculptor produced as much as during the entirety of her career up until that point, continuing at this rate through various illnesses. In her seventies she restricted her life to one room, but still worked with all her assistants. When Hepworth died in a fire in 1975 she would have probably been no more than a stone’s throw away from her tools.

Jonathan McAloon is an arts writer and book critic living in Newcastle

All images courtesy Bowness and The Hepworth Photograph Collection