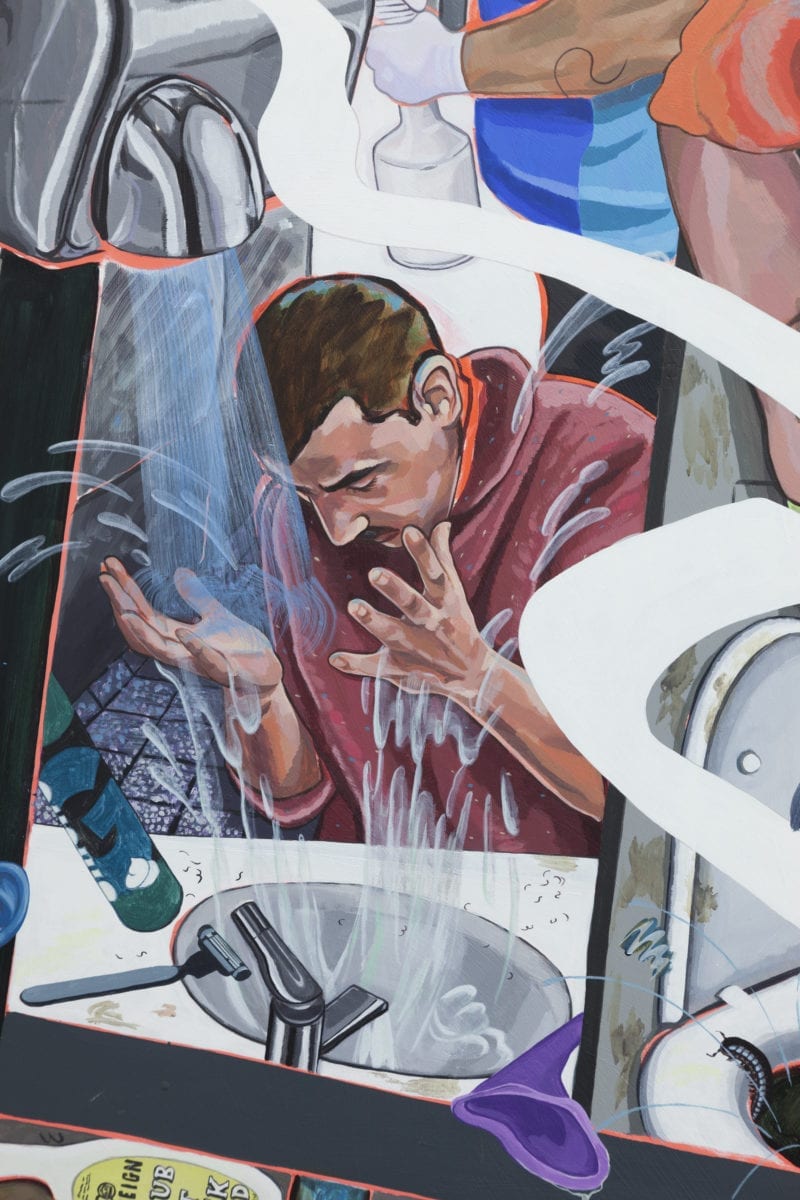

You need to pay attention when looking at the paintings of Flo Brooks. The experience is not unlike that of barging into an intensely messy bedroom unannounced, with objects, gestures and little details to see on all sides. Every surface is filled, every shelf and washstand, while the subjects of the paintings are caught mid-gesture. The detritus of capitalism—endless items that suddenly seem utterly unnecessary amidst the clutter—is shown alongside the cleaning products used in their upkeep, as well as the often unseen labour that goes into this process.

Brooks himself is a transgender person, and his personal experience of transitioning through Hormone Replacement Treatment (HRT) has directly informed these works—often in subtle, playful references and clues that can be detected in labels on the many bottles, tubes and other products displayed in them. The frantic multiple narratives that run through Brooks’s paintings also speak to his own encounters and relationships in flux, whereby societal expectations and interactions are upended and experienced anew.

The scenes in your paintings are taken directly from everyday British life, and you often explore community in your work, whether family, friends or other types of support networks. Why do you take these as the primary subjects of your work?

I suppose it feels fundamental to think critically about the ways we connect with each other, and what this might look like in our own lives. I make sense of things through lived experience, through intimate relationships and the communities I’m a part of, whether that’s the rural community I grew up in, queer and trans communities, art networks, my blood family, or whatever, they all contribute enormously to my own sense of self, how and where I feel I belong, and the ways I envisage collective identity. Part of my approach to making a painting is figuring out how I can integrate numerous voices and subjectivities into a visual narrative (whether that’s within a singular work or a whole series) so that it pushes beyond a linear or hierarchal framework, whilst also just telling a story.

A couple years back I overheard a primary school teacher tell two kids at an exhibition of some of my paintings that “they’re thoughts” when the kids asked what the “floating bits” were surrounding the figures in the images. I thought that was a really beautiful interpretation. I’m interested in the ways I can make visible these different, often divergent strands of knowledge—the “thoughts”—exposed to us through our communities and networks, and show the ways these impact our interactions on a micro-scale.

Your paintings are presented in an unusual “cut-out” format, reminiscent of everything from comic-book strips to theatre sets and shop window displays. What led you to explore this type of presentation?

I guess several things. For one, I was really attracted to wood and board as a painting surface; it seemed to allow more flexibility in terms of the shapes I could create using a jigsaw or hand saw, and I love the weight of the materials as opposed to the lightness of canvas. There’s an interesting tension for me between the heftiness of the material and the fluidity of movement and narrative I’m attempting to get at in a painting, I want to see how far I can push it. I also pull from many of the reference points you mention, and the cut-out format often echoes the action or motion of the body/bodies in the work, the architecture or space that’s being described, or a motif from something relating to the narrative.

You have also worked with collage, often accompanied by autobiographical texts. There is something distinctly scrapbook-like about these works, deeply personal and drawing directly upon the past. What is your relationship to nostalgia, and particularly to your own teenage years?

Ha! The juicy stuff! My relationship to nostalgia is complicated and I’m a massive cynic too. For me it generally feels complacent, apolitical and fairly smug. It’s also so connected to privilege. I feel like it’s just repackaged and sold to us in a sort of “we’re in on the joke” way—but, like, what joke? And really who’s actually in on it? You see it in these romanticized Enid Blyton-esque train adverts in the South-West (a lot of people in the Plymouth art community have talked about this at length), chivalry, gin and all that.

Also, within queer networks, there’s the danger of fetishizing and romanticizing earlier gay visual cultures, especially amongst people of my generation and those who are younger, which I’m susceptible to as much as anyone. It’s complicated because everything is commodified and appropriated nowadays, I want to learn from older generations but still stay critical and grounded in the present, and it’s a lot of work to do that, especially when everything seems to get coopted and made into a t-shirt on the high street.

I don’t feel nostalgic about my teenage years at all, I’m so glad they’re over! But I can look back now at that period of time and feel an inkling of love for myself that I hadn’t felt before, which I’m thankful for. I enjoy hearing and reminiscing about all the cringe worthy teenage clichés as much as anybody, but having been through two puberty’s and one as an adult, no thanks, not again!

How have your own experiences as a queer and transgender person informed your recent work?

My most recent work was a solo show called Scrubbers at Project Native Informant, London, in November 2018. It consisted of five acrylic on board paintings, which explore ideas around cleanliness, normativity and labour (amongst others things). The works follow a fictional commercial cleaning company, ‘Scrubbers’, as they work their way through a number of institutional spaces; the public toilet, the gym, the psychotherapy room, punctuated by coffee and cigarette breaks. Instead of working undisturbed into the night, their schedule takes them into opening hours, and both the cleaners and service users clash in space, undermining each other’s efforts to carry out the task at hand.

I was thinking a lot about the kinds of hygienic spaces I’ve traversed through my own hormone transition and mental health support, the ways these spaces are designed to clean, conceal and correct what’s considered effluent, abnormal or other, and how certain practices are rewarded, whilst others chastised. Rather than employing autobiography though, I wanted to evoke a kind of trans-ness and queer-ness through metaphor, visual pun and irony, provoking and belittling symbols of normativity and hygiene found within these spaces, particularly those associated with gender and sex.

So there’s a CIS security symbol stamped on a window frame in the psychotherapists office, a fly sitting on a transphobic sticker which alters the text to “men don’t have penises”, a bottle of cleaning fluid called “Aggressor” in the public toilet is knocked over and pissed on. I try to insert humour into the paintings because the subject matter is often kind of dense.

There has recently been greater exposure for a wider community of trans and gender non-conforming artists (notably Charlotte Prodger winning the Turner Prize); how has that impacted on your view of the art world, and of the world at large?

To see friends and artists I admire hugely getting recognition for their work is wonderful, regardless of whether they identify as trans or gender non-conforming. To be frank, I resent people jumping onto one facet of someone’s identity or experience as producing them in that way; Prodger’s work is amazing because it extends way beyond all that. But I don’t know what any of this means in terms of greater exposure. I’m generally very sceptical about any flood of interest surrounding a particular identity group, in the art world or outside of it. It sounds a bit negative but that is the culture we live in, where everything is capital and people are expendable.

Queer culture is really cool right now and even when individuals have the best intentions it can so easily skew into something superficial and tokenistic, and I’m including myself in all this; we’re all liable to it. I want to have sustainable and supportive working relationships with people that value my work as much as I do theirs, not solely because I’m trans or queer and that fulfils some kind of quota, or gives them a certain cache. Having said that, I also believe in the necessity of celebrating trans and GNC visibility, and the urgency of that now.