Take a quick browse through Western art history, and you will see that flowers have been a constant feature. The Dutch Golden Age was crammed full of still lifes, depicting huge bouquets of happy blooms in slender vases. A century or so later, Monet became obsessed with lilies, likewise Vincent van Gogh had a soft spot for sunflowers, and then came Georgia O’Keeffe in the twentieth century, whose enlarged flowers still move people today.

“If you think of cave paintings, humans have been recording the natural world since prehistory,” says Maria Devaney, galleries and exhibitions leader at the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art at Kew Gardens, London. “But specifically in the history of Western art, flowers and the natural world were an important part of medieval illuminated manuscripts, hand-painted on vellum for the great monastic and Renaissance libraries across Europe.” Devaney cites The Book of Kells as a classic example of this, with its extravagant and complex illustrations.

For Kew Gardens, the study of flowers is about more than just the aesthetics. As we know, botanical illustration marries art with science, and the institution has employed artists to paint and record new plants from around the world since the eighteenth century. This form of illustration is unlike more painterly still life captures of flowers in that they have to be scientifically accurate to every last detail. The work is still valued among botanists today and the images have become a simple way to share knowledge of different species.

“There is an element of the everyday about flowers, which botanical art asks us to pause and contemplate”

“At the root of all botanical art is the investigation of nature and the scientific recording of the detail of a particular plant,” says Devaney, who puts together exhibitions using Kew’s archive of over 200,000 botanical images as inspiration. “What began as a purely decorative effect developed into an important aspect of science coupled with the artistic sensibilities of composition, demonstrating the artist’s great skill in line drawing and replicating the exact colours found in nature.”

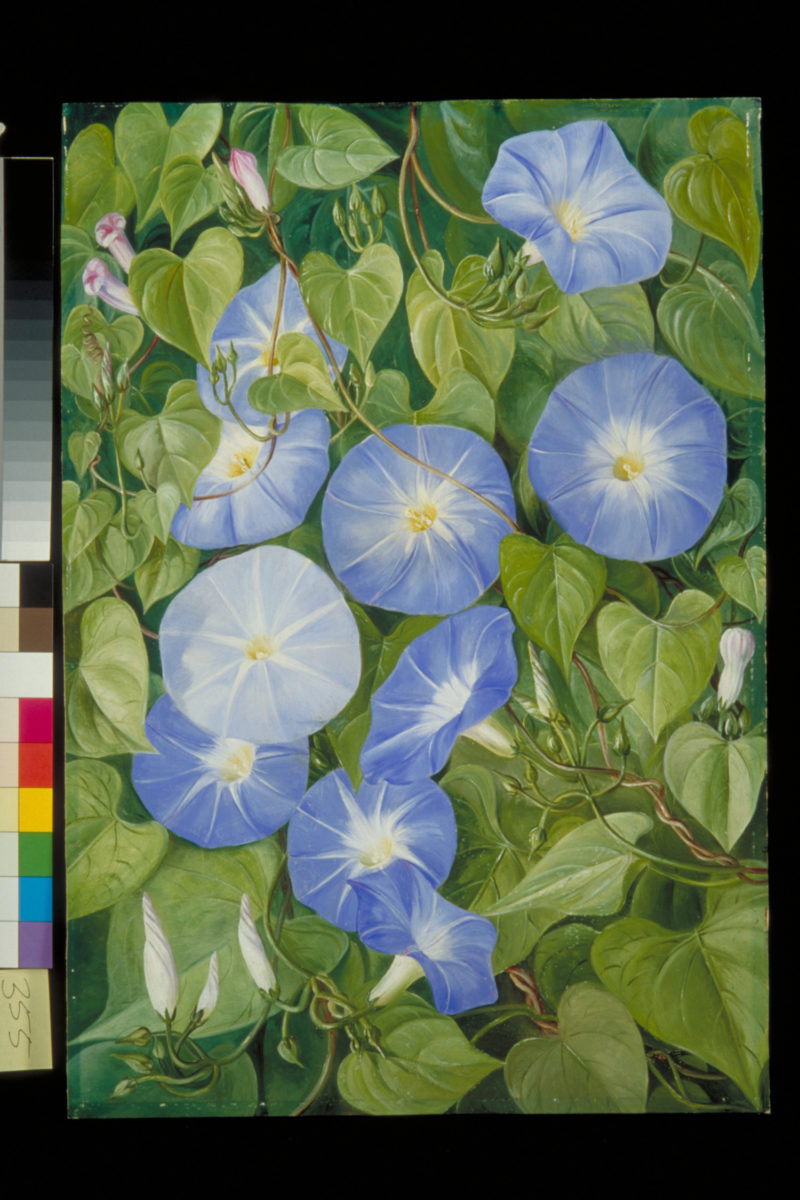

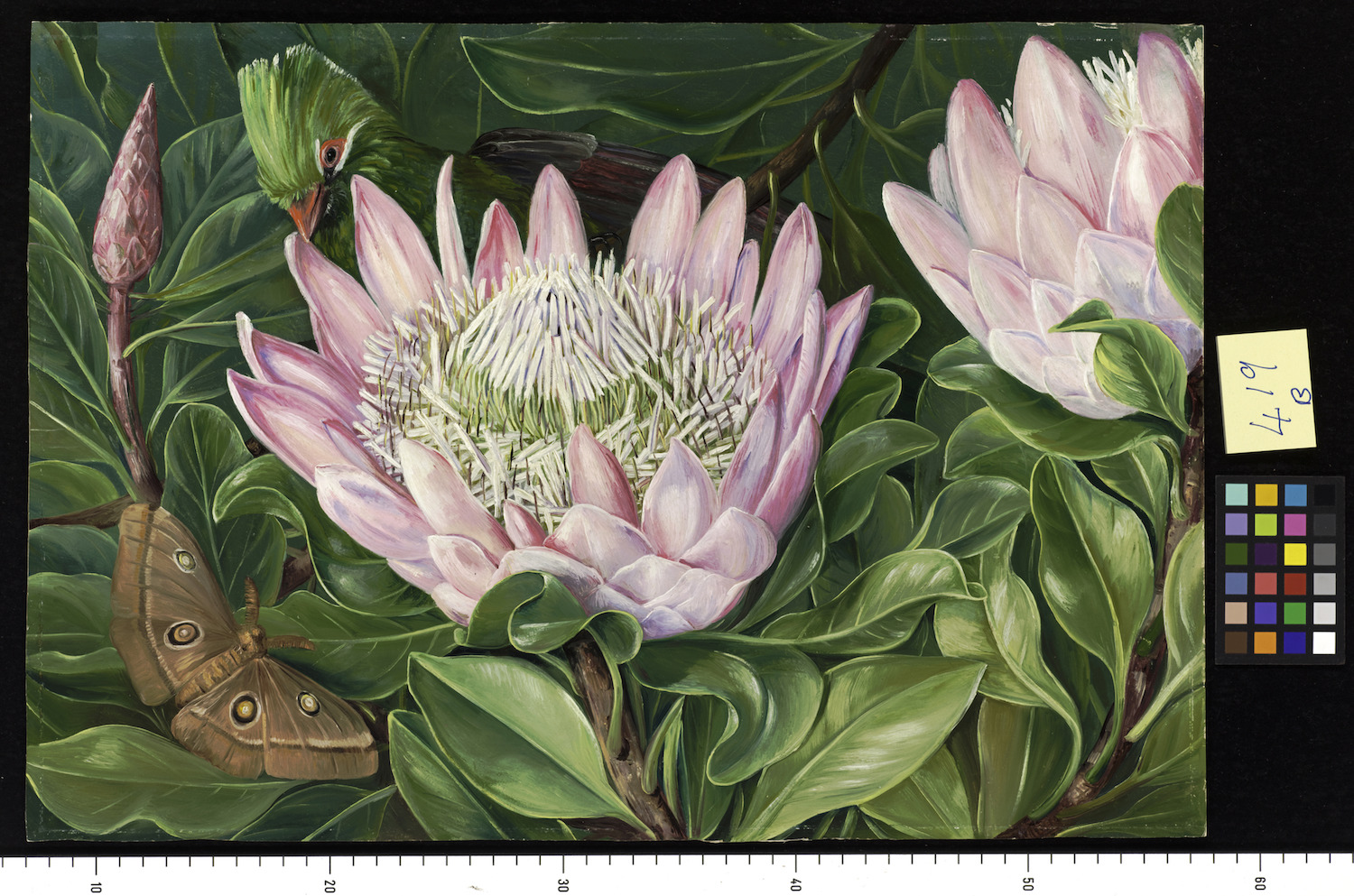

- Left: Marianne North, Flowers of the Waratah of New South Wales, 1880; Right: Marianne North, Morning Glory, Natal, 1882 © RBG Kew

The detailed nature of botanical drawings is often what’s so enthralling about them, and for the artists who dedicate their lives to achieving this kind of perfection there is ample inspiration. Devaney sees flowers and plants as a living resource for artists, allowing them to comment on society and our connection to the natural world.

For Australian-born, London-based botanical artist Lucy T Smith, the appeal of depicting flowers is that it elevates the everyday. “On the one hand there is an element of the everyday about them, which botanical art asks us to pause and contemplate,” she says. “On the other, there is the element of the exotic, unusual and striking about the more rare plants that people travel the world to see.”

Smith has been creating plant illustrations for Kew Gardens for twenty years, and there’s an elegance and fragility to her pieces. It was from looking through historical botanical illustrations of Australian plants that the artist was inspired to try it herself. “Then one of my first commissions was to draw plants, in return for being taken on field work to a deserted island in Australia. From there I was hooked,” Smith says.

The artist approaches her works with her head and heart. “I really enjoy that mix—being analytical and showing a truth, but at the same time embodying the subject with some of the love inspired by its beauty and uniqueness,” she says. “It’s about getting the right balance between the two.”

According to Smith, we keep coming back to flowers because natural forms are inherently beautiful to humans. “They possess pleasing proportions and shapes to which we are intrinsically attracted,” she says. “As a botanical artist, I seek to capture the symmetry and patterns in plants, the way the light falls on them to enhance their forms and colours.”

“Plants have tons of personality. I’m particularly inspired by city plants and weeds“

In contrast, Australia-born, New York-based illustrator Christina Zimpel sees flowers and plants “as almost human” so much so that she draws them like portraits. “Plants have tons of personality. I’m particularly inspired by city plants and weeds, and their ability to take over even the smallest crack,” says Zimpel. “Greenery, or the lack of it, used to make me homesick for Australia. I wasn’t really happy in New York until I had a garden. Brooklyn and the back garden is a microcosm of inspiration for me.”

- Works by Christina Zimpel

The illustrator typically uses ink and pencil for her flower and plant images, and her liberal use of colour feels expressive, though the shapes of the flowers themselves are kept simple. “Plants are a challenge to draw, it’s easy to over think them,” says Zimpel. “I came to realize that I just wanted to simply evoke a feeling of their beauty and not get bogged down.”

Zimpel sees her attraction to flowers as the same as everyone else. “Who has been outside and not experienced the awe of nature? Artists can depict that feeling over and over again,” she says. “Its power and beauty connects us all.”

While flowers could be seen as a traditional subject, it’s the illustrator’s non-traditional approach that charms the viewer. Like Smith, Zimpel wants to embrace the unique beauty of flowers. “I don’t dwell on accuracy of colour or structure, so all kinds of hybrids can emerge like a city garden,” she says.

London-based artist William Farr is more drawn to the physicality and texture of flowers. “From about the age of ten, I became interested in flowers. I loved everything about them: their structure, the way they were formed, the colours,” says Farr. “At school they filled my sketchbooks, and I would collect petals and leaves and put them in a flower press to preserve them and use them in my art.”

Farr uses flowers in his chaotic sculptures and installations, which he creates using found objects. For Farr, flowers offer a multitude of meanings for him. “I guess they describe ephemerality in a unique way, culturally they are cut and left to die,” he explains. “They are a sexual object indirectly and often misconceived as being simply pretty and joyous.”

William Farr, Broken Hearts

Flowers in conversation with objects inspires Farr, as it takes them out of context, and makes them become part of something else. While his works are busy and mad, it’s important to him that the flowers are still recognizable. “I haven’t consciously attempted to challenge traditional art, I love a lot of older work like Albrecht Durer, for instance,” says Farr. “I see a lot of similarities in his aquilegias to some of my images. I think the challenge with flowers is how not to disrupt them in a way that detracts from their beauty.”

Like Zimpel, Farr thinks his attraction to using flowers is simple. “It’s like saying ‘Why do artists paint portraits?’, we are here to hold a mirror up to the world around us,” says the artist. “For me it’s often about externalizing the internal world as well. I think the power of our imagination distorts and manipulates what we see around us, so I find it interesting to physically represent thoughts.”

Creative work inspired by nature helps us understand the complexities of our environment, and it also helps us connect to it on an emotional level. When you look at an image, a building, or even a piece of clothing that’s been inspired by flowers in some way, the artist reminds us that while we’ve man-made our towns and cities, when it comes down to it, we are just as nature-made as the flowers we love to gaze upon.