How can one better sense, and make sense of, our present climate emergency? Its concrete effects are felt unevenly and unjustly by communities around the world, who struggle against rising shorelines, burning forests, extreme droughts and shortages of food. But the scale and complexity of its causes and contributing factors (entangled in industrial supply chains, material infrastructures, government policies and consumer choices) exceed easy comprehension and, in particular, sensory experience.

Familiar images of sweeping data curves, factory smokestacks and melting polar ice do little to help bridge this perceptual gap. The crisis is all around us, but presents a challenge to our entrenched habits and ways of living: how can we learn to sense

better and, consequently, act and live better within the imperilled environment?

For London-based duo Cooking Sections

(otherwise known as Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe) food is a critical tool for understanding the transformations taking place in our physical environment, as well as grasping the systems, processes and histories that propel them. “Looking at food infrastructures and their interaction with different kinds of geopolitical and environmental realities led us to create interventions that we think of [as] generative realities or alternative futures,” explains Schwabe.

For example, in 2019 they conceived a mussel taco pop-up in Venice, California, where passersby were prompted to conflate the tasty molluscs with the engorged human tissues found at the iconic Muscle Beach, just moments away. This exploration of the site’s diverse past and present considered the impact of both human and non-human ecologies, along the coastline and within the wider city.

Another site-specific dining project, entitled Under the Sea There is a Hole, serves food and drink on suspended tables carved with irregular holes, in reference to the precarity of landmasses around the Dead Sea due to water depletion. If one is not careful, the ‘sinkholes’ might swallow up cutlery, glasses or even a dish, attuning participants to the perilous interplay between food consumption and geologic erosion.

“We have been habituated to consume more and more, to have everything available to us all year round”

The menu itself explores ways of eating that make the sea more fertile: one dish, called the Coastal Fortifier, is made of crops that bolster coastal landscapes, presenting beets garnished with sea rosemary, sea fennel, oyster leaf and samphire (sea asparagus). For those preparing the food, the recipe instructs: “Do not season with salt; all the leaves absorb seawater and already contain the necessary amount—taste the differences between their absorption capacities!”

Cooking Sections was first drawn to food as a guiding principle while taking part in a project in Kivalina, an Iñupiaq village in Alaska, which is facing displacement due to melting permafrost. The pair worked with the community to understand patterns of hunting and fishing, seeking to better understand the rapidly changing landscape and help legal efforts to pressure oil and gas corporations for accountability. “We became interested in food infrastructures as they reach all parts of the planet and all sections of society,” says Schwabe. “Food is extremely transgressive, and also something extremely class-based and racialised, defining a lot of social and economic structures in society.”

In recent years, Cooking Sections has exhibited at the art and architecture biennales in Venice, the 2019 Los Angeles Public Art Triennial, the 2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennial, and the Serpentine Galleries, but their work does not begin or end within these exhibition contexts. “Over the past years, we’ve steered towards the framework of creating long-term interventions,” says Fernández Pascual, “constructing spaces that become food networks, spaces of the production and consumption of food.” This is because, in part, cultural institutions are set up to offer exhibitions and events that last only a few months at most, whereas environmental questions (or those dealing with intricate networks of power, climate and commodity flows) take far longer even to begin to unknot.

One such ongoing project is the pair’sThe Empire Remains Shop, initially staged in 2016 at a space on London’s Baker Street, for three months. The endeavour takes its name from a speculative proposal for “empire shops” in the 1920s, which were envisaged to familiarise British consumers with food products from colonial regions (such as oranges from Palestine or Jamaican rum).

Cooking Sections’ version imagines “selling back the remains of the British Empire today” by inviting visitors to taste or buy produce and take part in an interactive events programme. During one of the project’s first dining performances, the duo recreated the original recipe for a Christmas Pudding published by the Empire Marketing Board, which included 17 ingredients from different places, primarily British colonies. The group attempted to source ingredients from the same regions cited in the original instructions, though many were no longer available due to territorial changes.

“We became interested in food infrastructures as they reach all parts of the planet and all sections of society”

Substituting those ingredients became a way of tracking shifts in global food networks. The pudding became more than a dessert, constituting, in Cooking Sections’ words, “an edible map” that charts the postcolonial world and the historical relations of consumption and coloniality. Though closed in London, The Empire Remains Shop is now an official franchise, allowing other proprietors to respond to their local geography (in June 2019, Grand Union opened the first new location in Birmingham).

Ever since embarking on this project, Cooking Sections has invested their primary efforts in “multiple year investigations that just seem to be getting longer and longer”. “You really have to think of these not as proposals or a combination of research,” says Fernández Pascual “but as active platforms that engage with multiple stakeholders.”

This is most apparent (and ambitiously realised) in the umbrella venture Climavore, which argues that the climate emergency necessitates a new approach to eating and cultivating food. Distinct from a carnivore, vegan or vegetarian, a “climavore” considers not only the origin of ingredients, their nutritional values and the ethics of their consumption, but also the agency of non-human entities in providing a response to human-induced climatic events (think back to the Coastal Fortifier recipe, which buffers against coastal collapse).

Cooking Sections made a takeaway meal from ingredients in Palermo, Italy, which diners could eat under the shade of single trees enclosed by stone walls. These micro-climate enclosures, equipped with sensors conceived in collaboration with agronomists from the University of Palermo, generated and visualised data on the growing instability of seasons. “We have been habituated to consume more and more, to have everything available to us all year round, making it difficult to diminish the need to change our habits,” says Fernández Pascual. “Climavore is about developing a capacity to adapt to a world that is changing rapidly.” Operating for the six-month duration of Manifesta 12, the project sought to emancipate food sources from the region’s highly politicised water infrastructure and reimagine relationships between the climate, landscape, city and audience.

“Our work tries to make the hospitality, food and beverage industry the site of responsibility”

These efforts have led Cooking Sections to focus many years of research on the specific plight of salmon. While working on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, the pair began to examine the effects of farmed varieties on the marine environment and the island’s economy. Heavily reliant on tourism, local restaurants have long turned to farmed salmon due to its attractive profit margins, but intensive production has introduced new parasites, diminished wild species and increased acidity in the waterways.

Cooking Sections developed a multi-tier approach to address this situation in Climavore: On Tidal Zones. The project (which has been running for more than three years) started with the construction of a multispecies oyster table in an intertidal zone, emerging and receding with the daily tides. During low periods the table becomes a site for workshops with local politicians and activists, events with schoolchildren and partnerships with chefs. Inhabited by seaweeds and bivalves such as oysters and mussels, the structure refocuses ecological attention on organisms that filter or oxygenate the water as they “breathe”, reducing contaminants and pollution. Cooking Sections also works actively with nearby restaurants, convincing them to find alternatives to farmed salmon.

“It was trying to revolutionise the whole food infrastructure on the island and how we think about what we grow,” says Schwabe. “Our work tries to make the hospitality, food and beverage industry the site of responsibility, rather than putting pressure again on the consumer. At the same time, let’s look at salmon and understand it as something that completely influences the way we see, taste, smell and understand the world.”

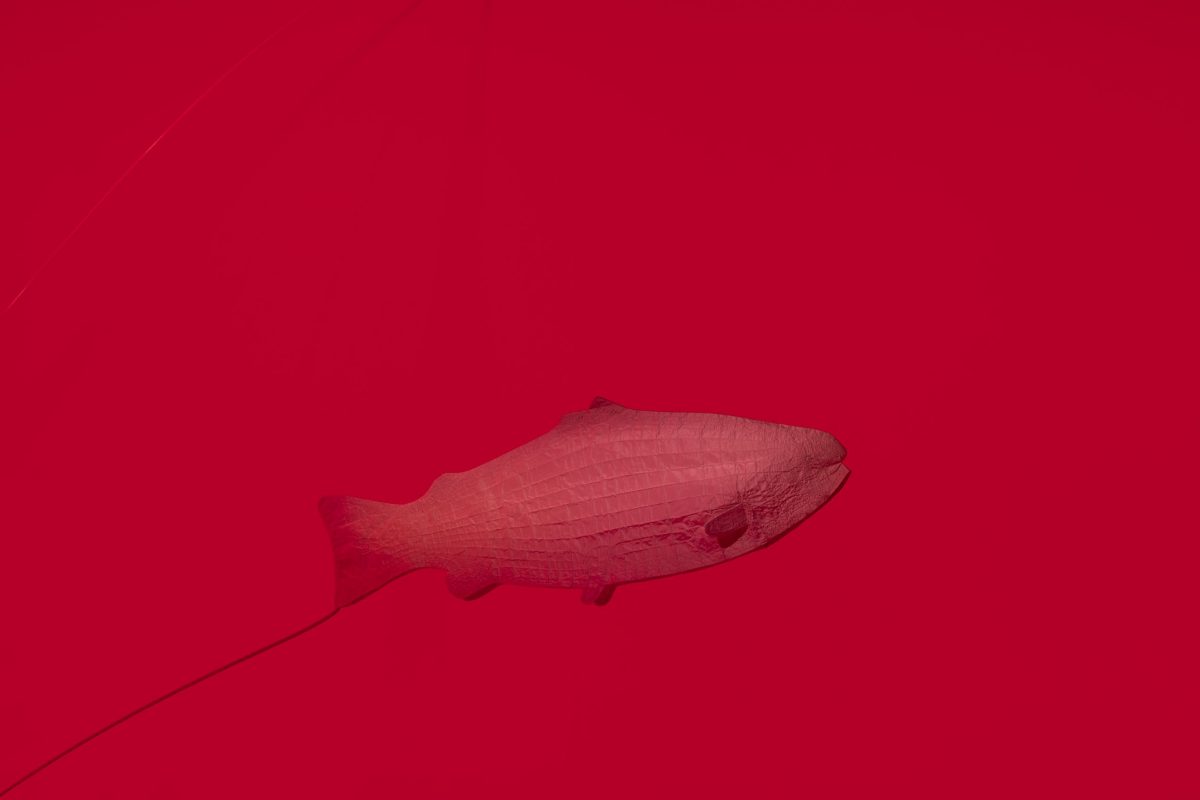

Cooking Sections brought this research together in Salmon: A Red Herring, an installation shown at Tate Britain (it is worth noting that the pair convinced the institution to remove salmon permanently from its food outlets), but it also takes the form of a publication.

The first in a new series of micro-format books underlines the absurdity of how “customers can buy ‘authentic Scottish salmon’ from a company registered in Jersey, owned by a Swiss bank with Ukrainian and Norwegian investors, floated on the Oslo Stock Exchange and using imported Norwegian genetic material”. Reflecting the artificial coloration of farmed salmon, modified via its feed, the pages move through an industrial gradient of “salmon” hues that follow the trademarked SalmoFan colour scale.

A farmed salmon is no longer salmon, the project suggests, but a genetically modified, colour-corrected image of itself. Sensing such transformations, however subtle, is essential if we are to unlearn destructive habits and better adapt to a fragile, changing world.

Madeleine Morley is a design writer based in Berlin

This article was first published in issue 45 of Elephant