The artist, exhibition organiser and founding member of the South East London studio-cum-gallery reflects on the pitfalls of artmaking today and what can be done to make the scene better

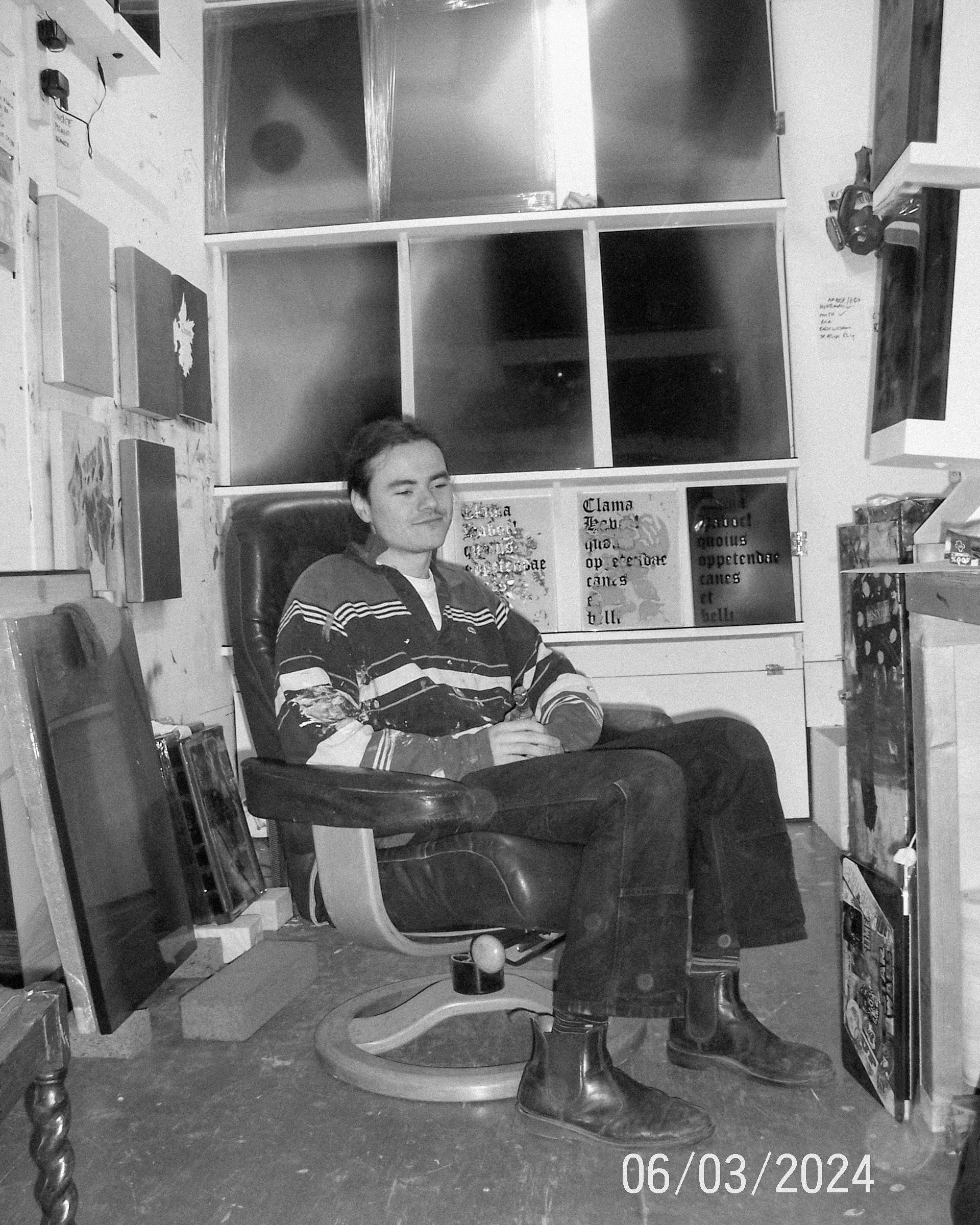

It is a rainy November afternoon when I jump on a Zoom call with Billy Fraser, the serious multitasker and self-professed workaholic behind Collective Ending – the Deptford-based, artist-led studio and gallery complex he co-founded with a group of fellow young artists, writers and curators in 2019. A graduate of Chelsea School of Art and Design, Fraser stood out to me for his wholeheartedly collaborative and can-do approach to being part of London’s creative scene; one which sets him aside from many of this industry’s stakeholders, particularly from the greedy galleries and artist studio providers blatantly profiting off emerging artists’ sweat and tears.

Three months fast-forward from that virtual chat, the points raised by Fraser during our conversation are as relevant as ever: “artists are taken advantage of in as many capacities as possible by the gallery ecosystem,” he says. “They are cannon fodder: this scene is designed for you to believe that, as an artist, you are only going to say something out of turn to collectors.” Afraid of any missteps, artists, explains Fraser, engage in gallery representation because it is meant to look after their best interests. With gallery commissions traditionally falling anywhere between 30 and 60 percent of an artwork’s total sale price, it is hard to imagine how creatives in the early days of their career could pay the bills with the remaining proceeds. But gallerists aren’t the only ones playing it dirty.

When it comes to studio spaces, “artists are just at a very rock bottom,” Fraser says. All you get nowadays is “a one-year lease for a damp room with a leak, no guarantee of tenure and a one-month eviction clause” – a grim prospect made even drearier by the British capital’s growing cost of living and exponential rental crisis. Despite the establishment of Mayoral initiatives such as the Creative Land Trust, which since 2019 has helped workspace providers secure long leases, and Creative Enterprise Zones, a programme aimed at designating areas wherein local councils are invited to promote new spaces, the sector is still struggling to meet artists’ demand for long-term, secure and affordable studios, a recent survey by UK charity Acme finds. Based on the results of a quick search on the London Artist’s Studio Finder database, the average price ranges from £115 a month for a 45 sqft art booth in Hackney Wick to £695 pcm for a 285 sqft bright floor unit in Willesden Junction.

But what alternatives are out there for those seeking to pursue art on more reasonable terms?

In Fraser’s case, stability came from a narrative shift: “all over the country, you have loads of artists working in their little echo chamber, patiently hoping for someone to grace them with an exhibition or representation,” he says. But for those who went on to launch Collective Ending alongside him, “it seemed futile to sit around waiting for opportunities to come our way”. Rather, they made opportunities happen. Conceived as a “complementary ecosystem” gathering interdisciplinary understandings of art under the same mission, the studio-cum-gallery prides itself on putting the artists’ interests first. “Because we are artist-run, our morals and priorities always align with those of our members,” Fraser says. “And since it is us members paying for the whole building, [when exhibited at Collective Ending], artists receive a much higher percentage of their sales than they would at a commercial gallery.”

But greater artist profits are only a side effect of the platform’s community-oriented ethos. For the creatives part of the South East London art hub, which started out operating as a nomadic exhibition programme as early as in 2017 before finding its home in Deptford the following year, it is about leaning on each other’s expertise to support the wider emerging artistic network. Today Collective Ending comprises a dozen of in-house members, including curators Hector Campbell, Charlie Mills and Georgia Stephenson and artists Tom Ribot (aka [pɑːtɪk(ə)l]), Alia Hamaoui, Ted Le Swer, Yuli Serfaty and Harrison Pearce. Its reach and connections move well beyond the initiative’s physical space: “Collective Ending is much more than the sole people who currently have a studio here,” explains Fraser. “It is all those we have worked with and exhibited in the past.”

Since its inception, the project has come up with nearly 30 exhibitions, most of which hosted at Collective Ending’s headquarter, and turned the spotlight onto some 150 international artists, many of whom at their debut. A handful of its notable alumni includes Harley Weir, George Rouy, Pilvi Takala and Corbin Shaw. Last autumn, the platform outdid itself with First Edition; a month-long group showcase which brought together nine galleries – each one presenting a selection of artists – “as a resource for collectors and curators to explore collaborative possibilities for grassroots organisations and communities”. Rejecting the traditional commission model and the gatekeeping of sales, the event saw all galleries involved promote personalities they didn’t formally represent in a celebration of London’s eclectic art scene.

At the heart of Collective Ending, says Fraser, lies a desire to find alternative paths to championing artists from “a place of safety”, thus nurturing and preserving their talent from the threats of the industry. A reaction to the instability ruling the artist studio market, he began to think about Collective Ending after he and fellow founding members Ribot, Le Swer and Hamaoui were kicked out of their studios at V22 in Bermondsey. Coming from an art carpentry background, Fraser was never afraid to get his hands dirty: at the time, he was working on mezzanines and studio renovations alongside long-standing business partner Ribot. Today, most of his income stems from the building of several blue-chip galleries a year under a new company, London Art Services.

Aware of having a viable way out of the exploitation to which, as artists, they had been subjected by what he calls “the smoke-and-mirrors studios provider”, Fraser and the coalition of creatives formed on that occasion took over the spacious warehouse that is Collective Ending’s HQ to address the state of today’s art world. According to Fraser, who speaks for his individual experiences rather than for the platform as a whole, “exploiting artists is quite a profitable business”: “[artist studio providers] open a studio for eight months and fill it out with creatives committed to being in a certain space only to give up its lease and evict the same artists within a matter of weeks,” he says. While this might not affect creatives with the time and resources necessary to relocate their practice elsewhere, the inconsistency of such studio solutions represents a major impediment for those juggling multiple jobs to afford a career in the arts. Luckily, there are positive exceptions, too. In the long run, “I would love to be a provider like SET,” Fraser explains. “They are forever advocating alternative models, bringing the community in wherever they can and supporting the people they represent.” But, he adds, “I am first and foremost a practising artist”.

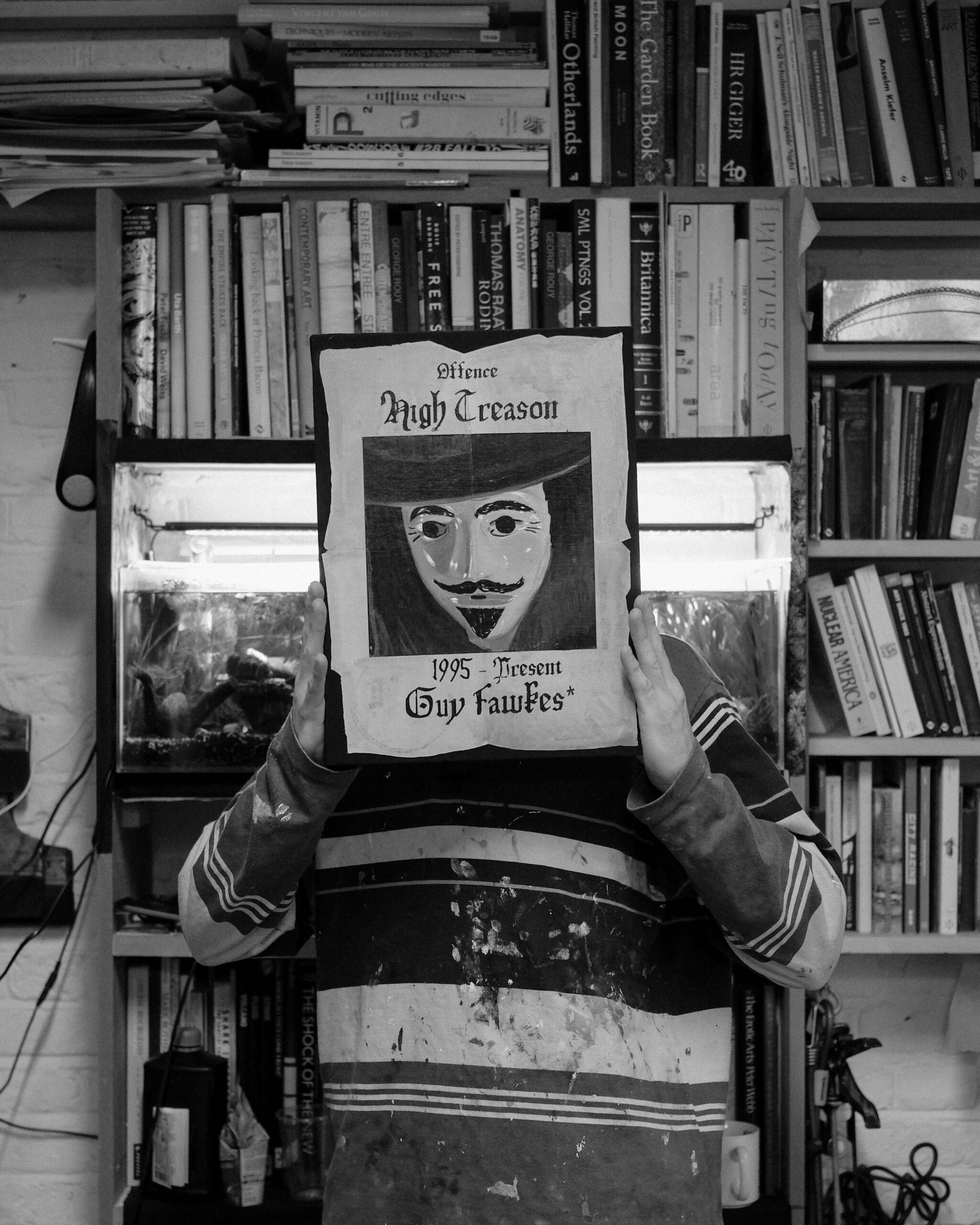

Experimenting across multiple mediums including sculpture and painting, through his craft, Fraser allows seemingly extraneous narratives, worlds and aesthetics to collide in his work. This is particularly tangible in his contribution to Tomorrow, Today, Yesterday, the recent group show he conceived for the collection and curatorial platform Modern Forms, housed within a Grade II listed building on Grosvenor Street. A dialogue between the genre-bending creations of Amba Sayal-Bennett, [pɑːtɪk(ə)l], Jesse Pollock, Florence Sweeney, Grace Woodcock and Fraser himself, the event surveyed six of the most unconventional and young contemporary sculptors active in London right now. Part of the exhibition’s offerings was a series of faux-amber tablets which, featuring fossilised aquatic life, bats, bees and more, revived the centuries-old taxidermy tradition in an uncanny investigation into class, climate change and the inner dynamics of human survival.

In Fraser’s conception of art, the commitment to creative innovation goes hand in hand with and is motivated by a participation in the challenges that shape our times. Following the escalation of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, in January, Collective Ending launched a poster and billboard campaign directed at Lewisham’s MP Vicky Foxcroft, who had abstained from voting for a ceasefire at the House of Commons in November 2023. Sparked by the politician’s and the wider British government’s lack of action to stop Israel’s ongoing killing of Palestinian civilians, the Deptford art powerhouse compiled an extensive list of petitions, learning resources, human rights papers, fundraising drives and activist groups aimed at fostering further engagement with the cause.

While far more critical in its scope, Collective Ending’s Gaza Action is a project that exemplifies Fraser’s thoughts on the urge for transparency and honest conversations within the art sector. Hijacking the silence of fellow cultural organisations in relation to the non-stop violence targeting Palestinians – let alone the overt censorship impacting artists speaking up against it – its “this billboard refuses to comment on genocide” slogan implicitly called the whole art system into question. At a time when galleries and curators alike compete to, on paper at least, offer exhibition programmes which embrace diversity, inclusivity and decolonisation, the disconnect between the empty preaching of many cultural institutions and their actual stance has become apparent.

Similarly, the picture painted by the Instagram accounts of too many artists and artistic hubs, Fraser claims, isn’t but an idealised depiction of a far-from-perfect reality. “You rarely hear any stories about those artists who have grafted endlessly to get to where they are today, those who have had to find a way to survive when they weren’t selling any of their works,” he says. “I think it is time for the art world to get over its problem with privilege: as an artist, you should be able to work for galleries, have a separate business on the side, fit kitchens or work at a restaurant without feeling ashamed, as long as what you are doing facilitates your practice.”

As for his thoughts on the future of art, Fraser has no fear to put it bluntly: “People should ask themselves the following questions: ‘can art still be considered a public space, a space of reflection and progress?’”, he says. Ever since it first came about, art has always engaged in the difficult conversations of the present. “If it can no longer do that,” Fraser concludes, “then I am not sure what is even left of it. That is why I admire everyone willing to use their voice to push for the change we are all hoping to see.”

Written by Gilda Bruno