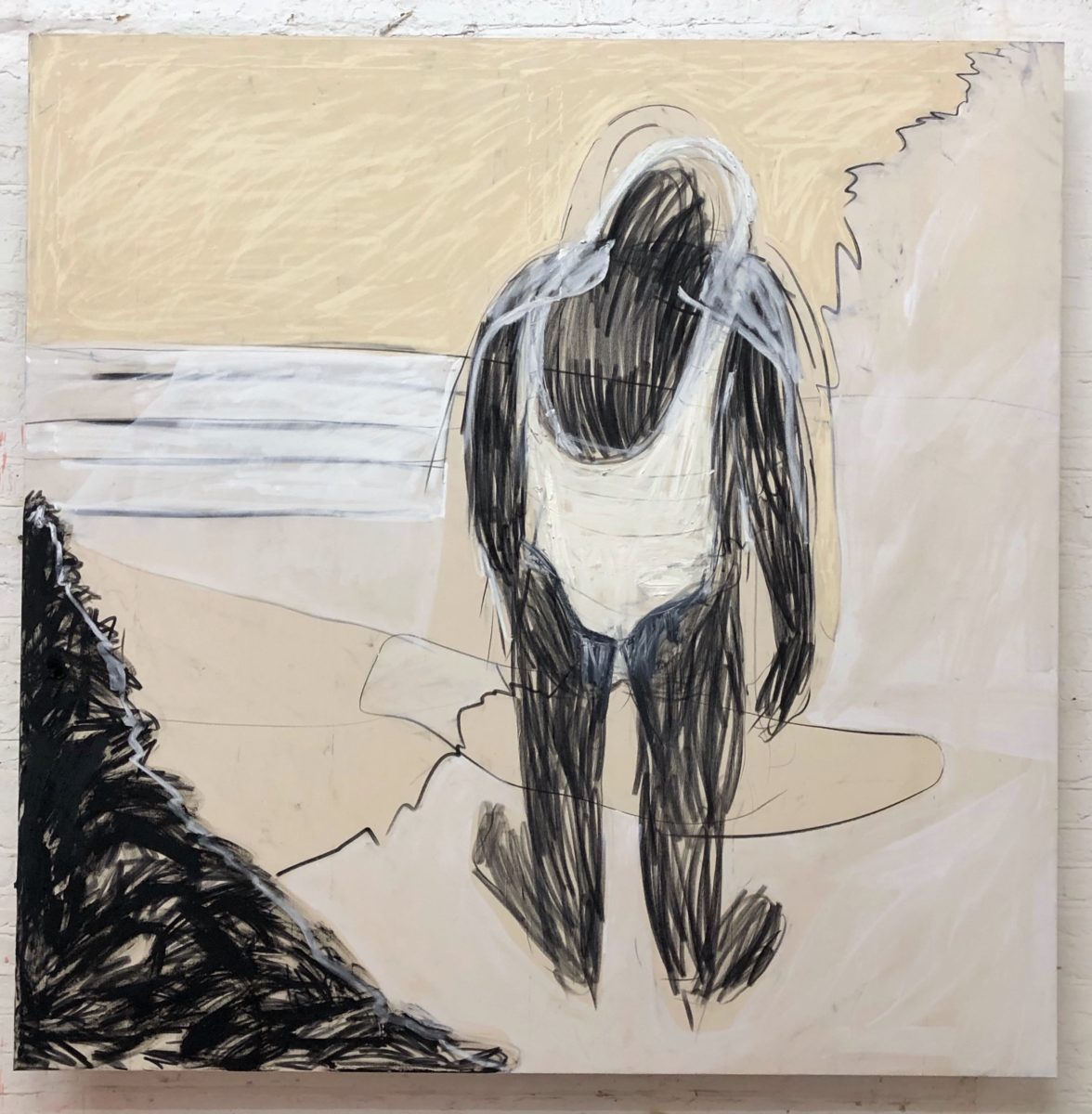

Born in Berkeley, California, Emma Fineman works primarily across painting and drawing, though her willingness to allow her various themes to guide the form—often melding the two mediums—is an essential component of her practice. Working over the summer at Porthmeor studios in St. Ives, south-west England has allowed the artist to fulfil a long-held interest in how images can be created at 1:1 scale, while retaining her roots in figurative abstraction.

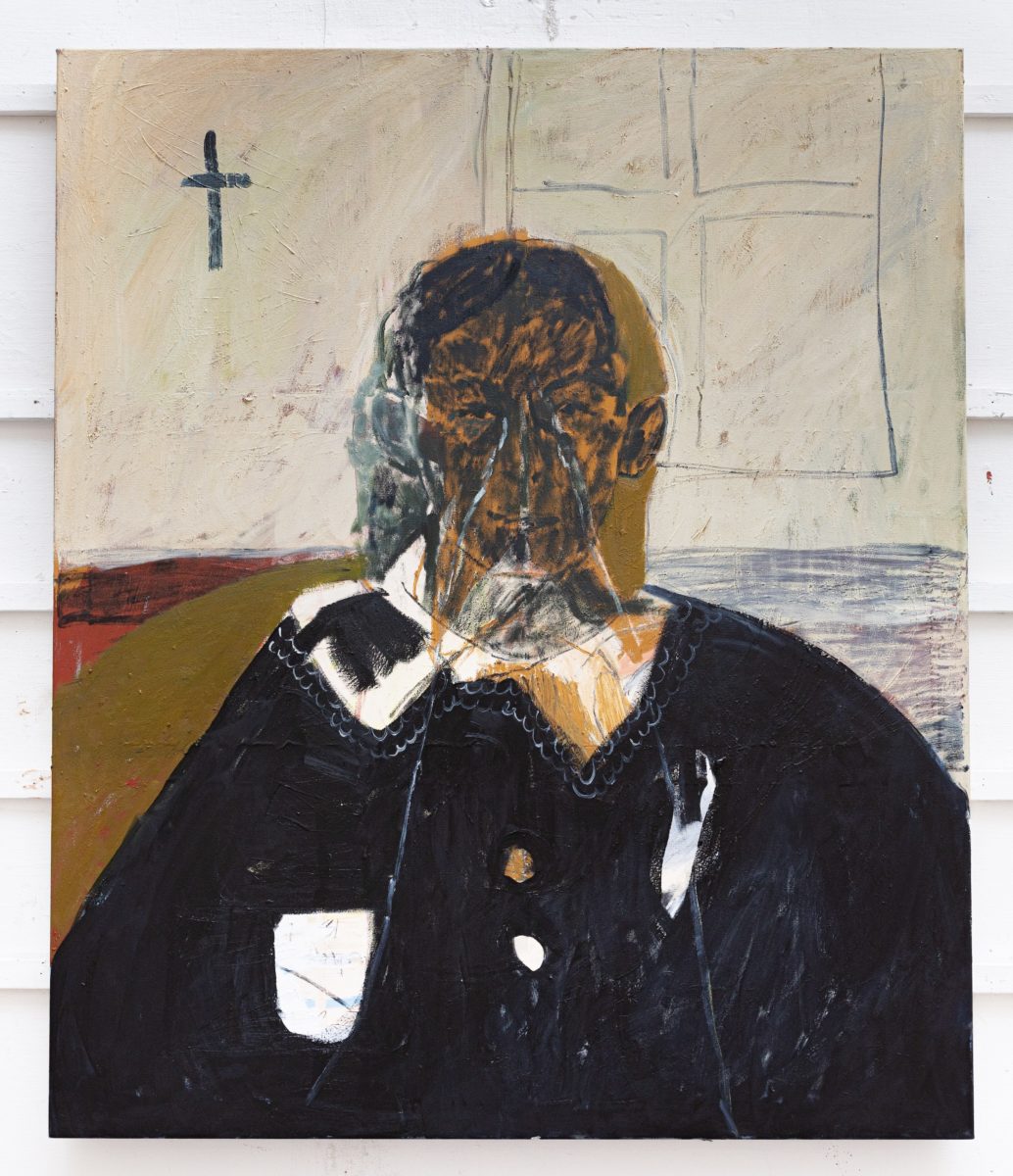

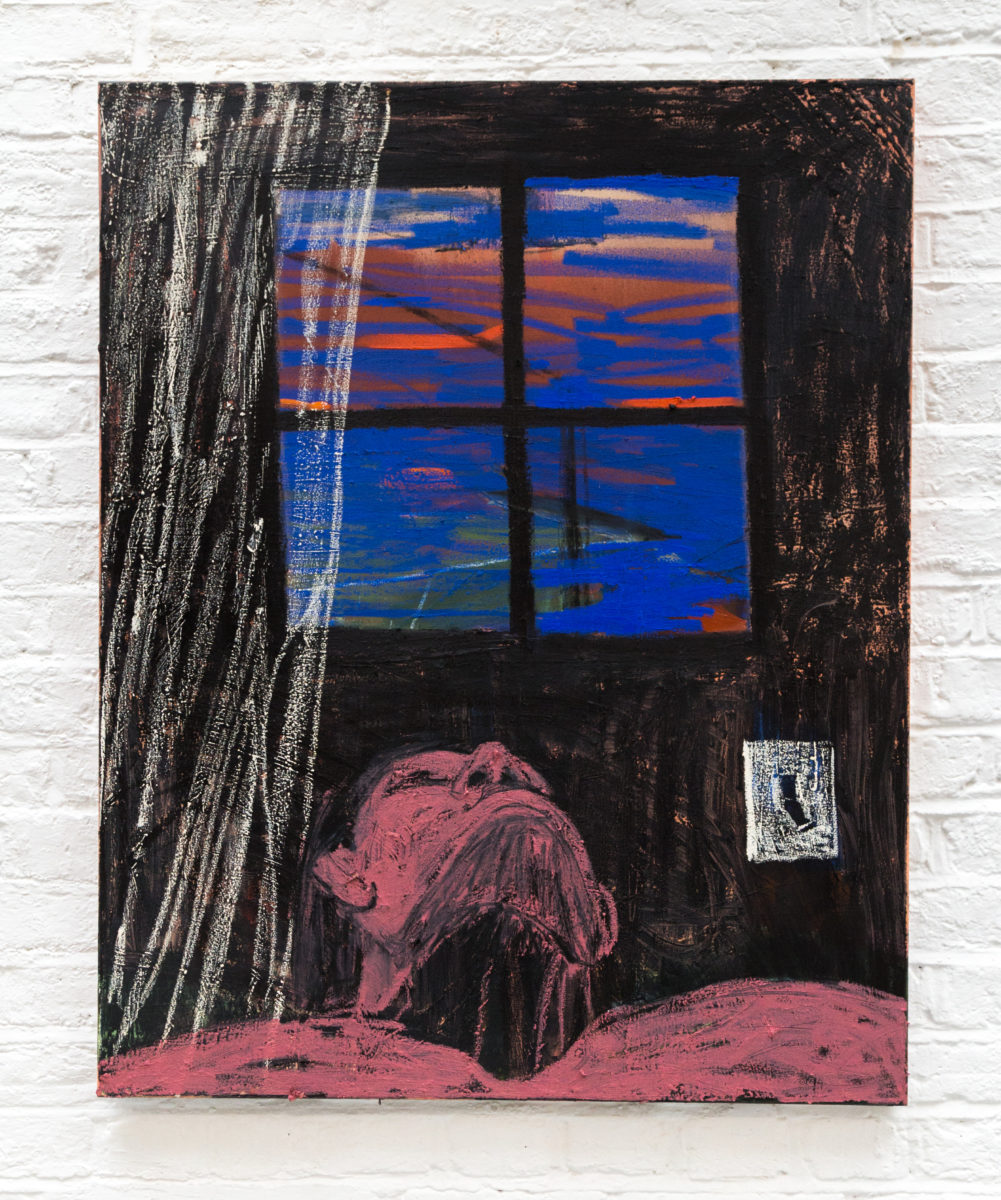

As a painter, Fineman works strictly from memory, enabling her to explore not only the relationship between object and representation, but also between object, perception and representation—encouraging slippages, discrepancy and multi-dimensionality in her work in pursuit of authenticity. Fineman’s work inscribes her own relationship with memory, while also serving as a wider comment on how interiority manifests itself in art-making.

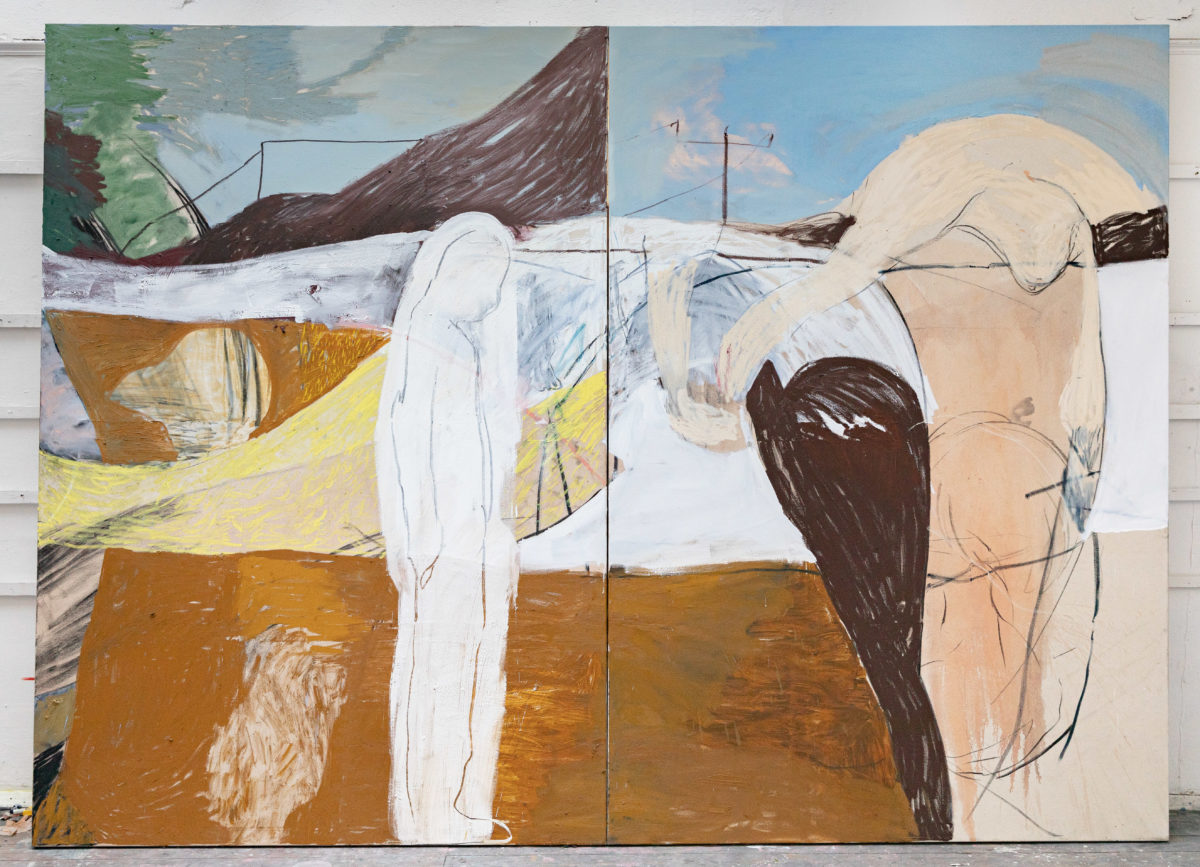

Shelter in Place and Displacement, two works created in St Ives this year, showcase Fineman’s use of an earthy palette to restrict the motion of her otherwise vibrant work—a reflection of the world in lockdown. In Shelter in Place, a figure sits upright on the right hand side, their eye line drawn out towards the busier portion of the canvas where two figures occupy a darker, more uncertain scene.

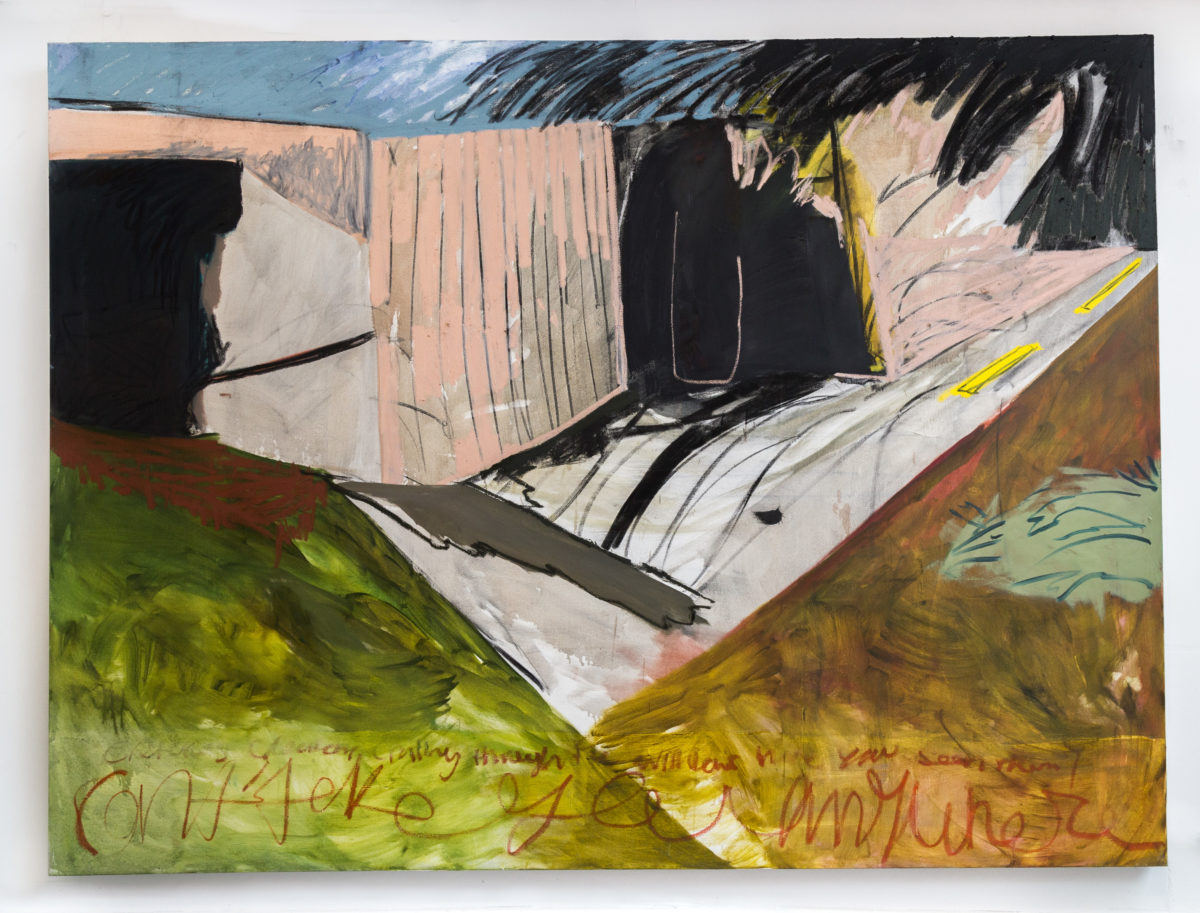

“Maybe it’s encrypted, but painting is a visual language for me. By using oil bar or charcoal, there’s an aspect of writing”

Discussing her exhibition Realms of the (Un)Real at Public Gallery (2019), Fineman situated her work within a confessional tradition, drawing some inspiration from the visual style of the outsider artist Henry Darger. She compares the interplay between painting and drawing with journaling: “Maybe it’s encrypted, but [painting] is a visual language for me; and that’s where choice of medium is so important to me. By using oil bar or charcoal, there’s an aspect of writing,” she says.

Fineman continued this exploration of self-fashioning in May I Have Your Attention Please, a solo exhibition at Beers London last year. Pulling back from abstraction and turning instead to self-portraiture, Fineman reimagines herself as Joseph Grimaldi, a popular entertainer from the early nineteenth century. In it, she explored social media’s role in crowding out more nuanced representations of emotion, in favour of extremity and simplification. Compared with the more sedate, ruminative faces of Fineman’s human subjects in her earlier work, these Grimaldi studies explore joy and sinisterness as uneasy counterparts, with a considerable range of canvas sizes emphasising the social media parallel.

Fineman’s experimentation across forms has more recently led to her being awarded the London Bronze Editions Prize this year, allowing her to continue work inspired in part by Nicolas Poussin’s The Adoration of the Golden Calf (1634); while at Porthmeor, she has been working on a life-sized sculpture of a calf, a subject also depicted in gold leaf and deep blues in her painting. Most recently, Fineman’s work has been featured in Begin Again, an online exhibition organised by Guts Gallery, with proceeds going to The Free Black University.