Mika Tajima was sitting through a Zazen meditation in Tokyo a few years ago. The innate quietness of the morning ritual was gently ruptured by the humming echoes and the breeze of the priest scooting around the crowd. A few months later, she was in New York, this time at a luxury spa that offered lunch break meditation for those in search of an escape from the corporate hamster wheel. In both times, Tajima’s phone was in recording mode to catch the subtle sounds of collective release and repose—different geographies and contexts offered similar bodily vibrations and audial energies. “I’ve been interested in recording sounds of something collective being produced,” the artist tells Elephant from her Brooklyn studio. “After sites of industrial production and technology,” she adds in front of a tall singular pink-coloured anthurium placed inside a geometrically shaped pot, “I became interested in noises of human energy being produced.” The recording sessions and the flower are parts of her new exhibition at Pace Gallery’s New York headquarters, titled Energetics.

Hannah Arendt titles on her studio’s bookshelf hint at Tajima’s inspirations for the show that feature textile paintings, rose quartz sculptures, flowers, and even scent. The greeter on the ground floor shows a line of flowers, such as mums, orchids and lilies. Each bouquet is lit by a UV light from above, letting bold floral colours glow and allure: “Coming into light and transforming under fluorescence connects with Arendt’s ideas on becoming visible and self-presentation.” As much as light, care on the artist’s end maintains the beauty as she will be replenishing the flowers once a week throughout the show’s run.

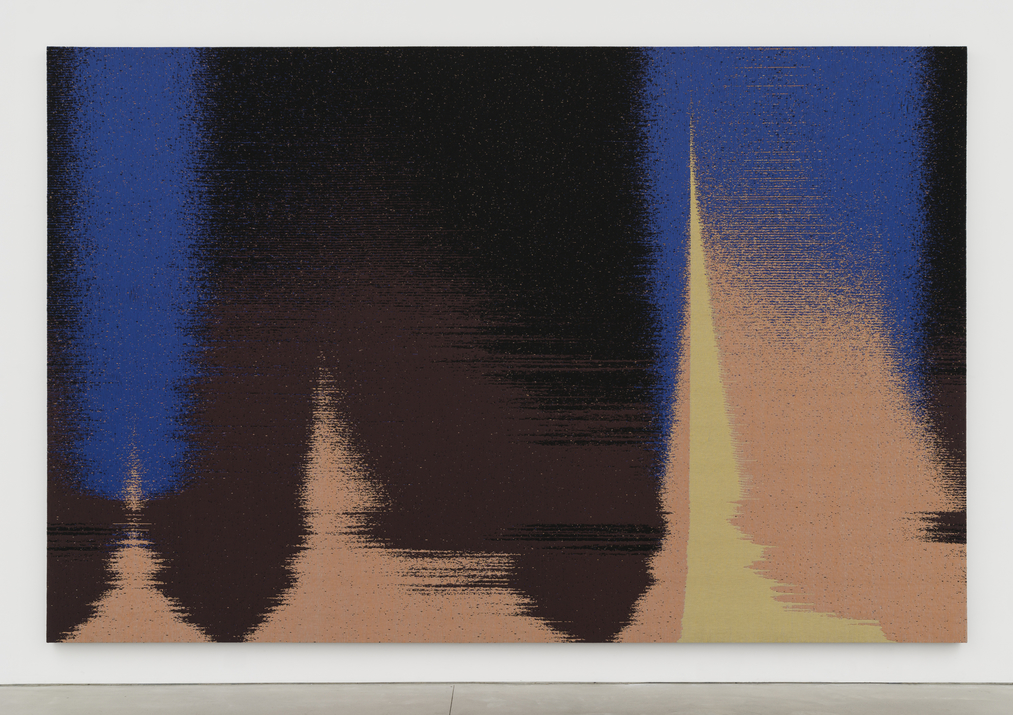

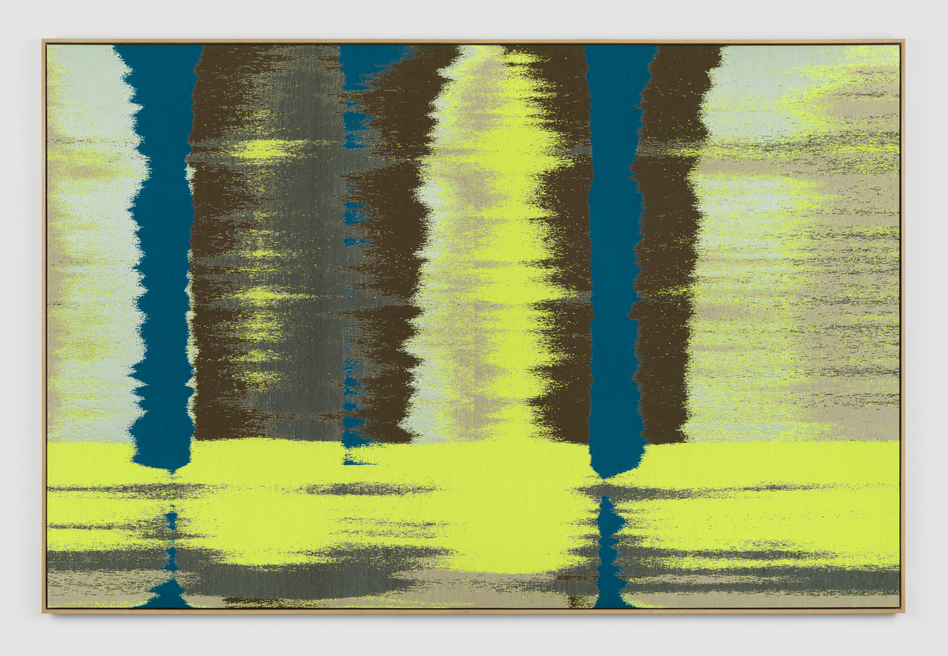

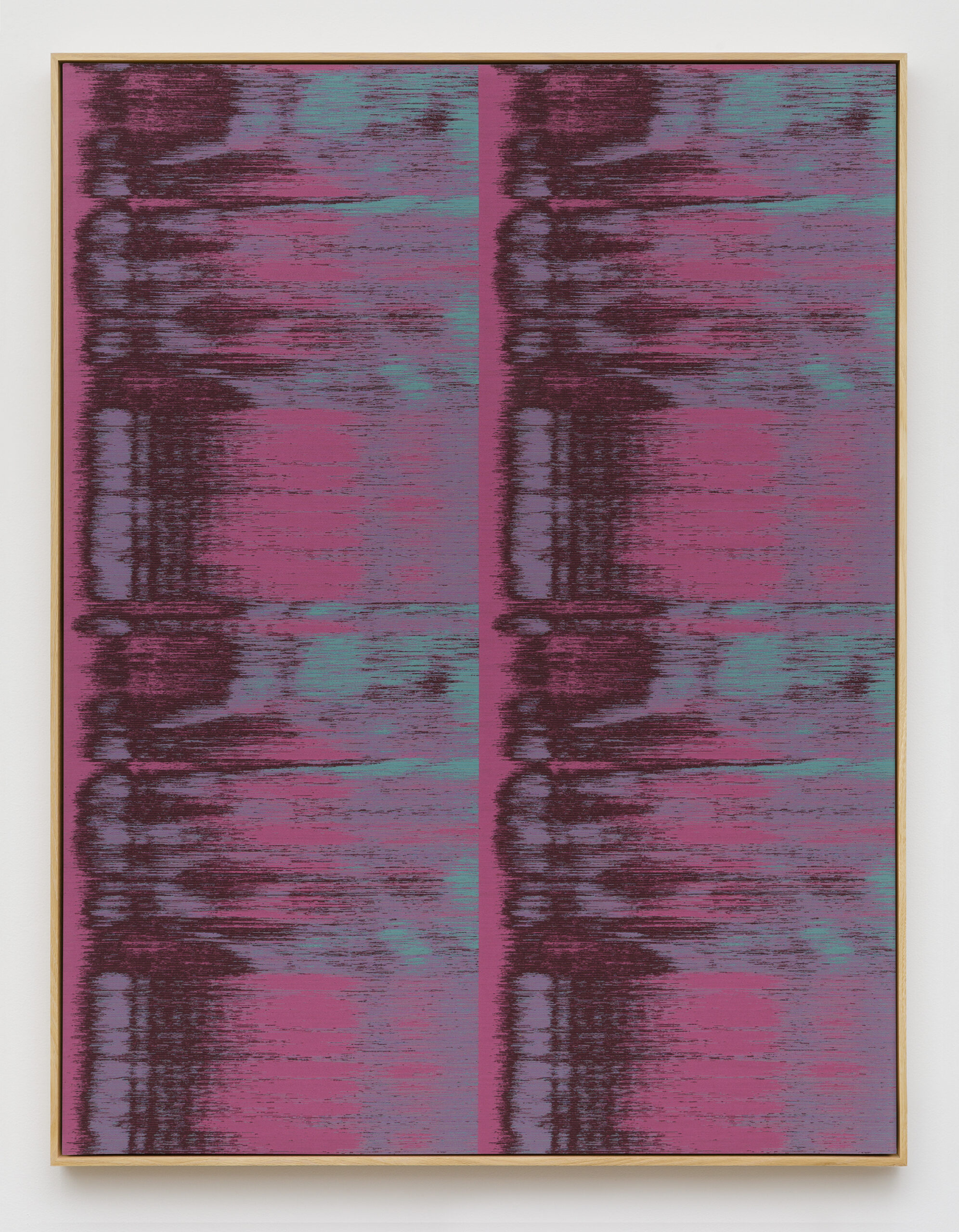

Different impressions of light reflecting their glare and heat onto colourful petals also tap into the artist’s intrigue for the psychology of the collective spirit. A desire to “visualize human energy production in the brain” has led to the show’s three cotton, polyester, and nylon paintings, titled Negative Entropy overall. Tajima worked with a neurologist to map out the human brain’s energy patterns while they performed a high-tech degenerative treatment on a patient to lower the effects of Parkinson’s. The procedure, which is called deep brain stimulation, involves sending an electric pulse to a patient’s brain to minimize muscle deterioration. The main draw for Tajima was a realization that the doctor has to listen to the auditory harmonics of the brain’s reactions while navigating the organ. “They rely on these auditory cues to know what they are doing in this experiential process, which is mind-boggling,” she says about her “wow” moment, which urged her to “represent this tiny invisible moment in a massive woven piece.” The result is a trio of large paintings which were created at a digital looming lab in Tilburg, outside of Amsterdam. The opportunity to weave in monumental scales led to paintings that reach as wide as 526 centimeters.

Tajima encountered the Dutch printing lab and assumed the desire to explore the minuscule human presence on earth at the same time, during the emergence of Covid in Europe and US. “Death tolls were flashing up on TV, and I had a realization of how tiny we are in the world,” she remembers. Blowing up a bare second in an individual’s most visceral function made the most sense—and she wanted to expose the gallery-goers to “a massive vision of humanness represented within one person.” For an eye unfamiliar with their source material, the paintings convey erratic abstractions, washed in one work with neon hues of yellow and turquoise and a nocturnal blue, dark pink and brown composition in another.

The human body is physically amiss throughout the show, but a myriad of homages to its mysterious operations linger. “Each work is a bit of a surrogate or a reflection,” the artist explains, pointing out that “humanity is woven into the paintings through one person.” Against the singularity of the paintings’ subject, the cerebral alchemy of the entire US population is the source of a sculpture titled Sense Object (January 1, 2023, United States). Tajima pulled data from Twitter on January 1, 2023, to collect traces of heightened ambitions, regrets, and resolutions folded into a day that is synonymous with new beginnings. “The emotional energy of such a day,” the artist admits, excited her “because some people are the most hopeful and the others are the most desperate.” A custom sentiment analysis program helped her analyze the emotions floating around the web. A positive tweet about the sun shining bright, for example, could be calculated as a display of positivity.

What Tajima explains as “the algorithmic mood of the country on the first day of the year” has been decompressed into a 5D memory crystal, nanolaser etched through a technology developed by a British scientist. While the chip has the capacity to hold even a billion years of archival data, the artwork contains a large nation’s whirlwind of sentiments within twenty-four hours. The glass disk sits on a pedestal-like chunky piece of rose quartz, a material Tajima also uses in a group of sculptures punctured with jacuzzi jet nozzles. An energy-holding natural stone, the material is also piezoelectric with the ability to maintain electric charge. The artist punctured the earth-mined stone’s natural beauty with drills to install the air pumpers, creating various points of relief and release throughout each stone block. Easily comparable to orifices or nipples, the nozzles are bronze-cast from commercial versions at the artist’s studio. A personal fascination to “pinpoint invisible air pressure within a form of the body” inspired Tajima, as well as the innate human desire “to create diagrams of infrastructures that are unknown to us.”

The human urge to solve the body’s mysteries through energy flows—from holistic rituals such as acupuncture and chakra yoga to the science of neurology—fuels Tajima’s practice. In her research, any path of attempt intrigues her, from the commercialized promise of office-break yoga or the colours of ergonomic office chairs to the technology-pushing scientific studies. “We are always trying to map out different systems, but the reality is we never fully know how this life works,” she says.

Written by Osman Can Yerebakan