In Zeinab Saleh’s 4 Star Wedding, ceremonial home video footage from Saleh’s family archive is cut to Mariah Carey’s song The Impossible. “The love that you gave to me has pulled me through,” Carey sings in her smooth noughties voice as brides, grooms and guests dance and sway, captured in the saturated tones of VHS. In time to the song, newer footage flits onto the screen: flowers unfurling, a butterfly fluttering its wings. The video, which was exhibited in Saleh’s degree show at Slade and screened at Het Nieuwe Instituut, reaches forward in time and back again, as Windows 2000s logos fade into black.

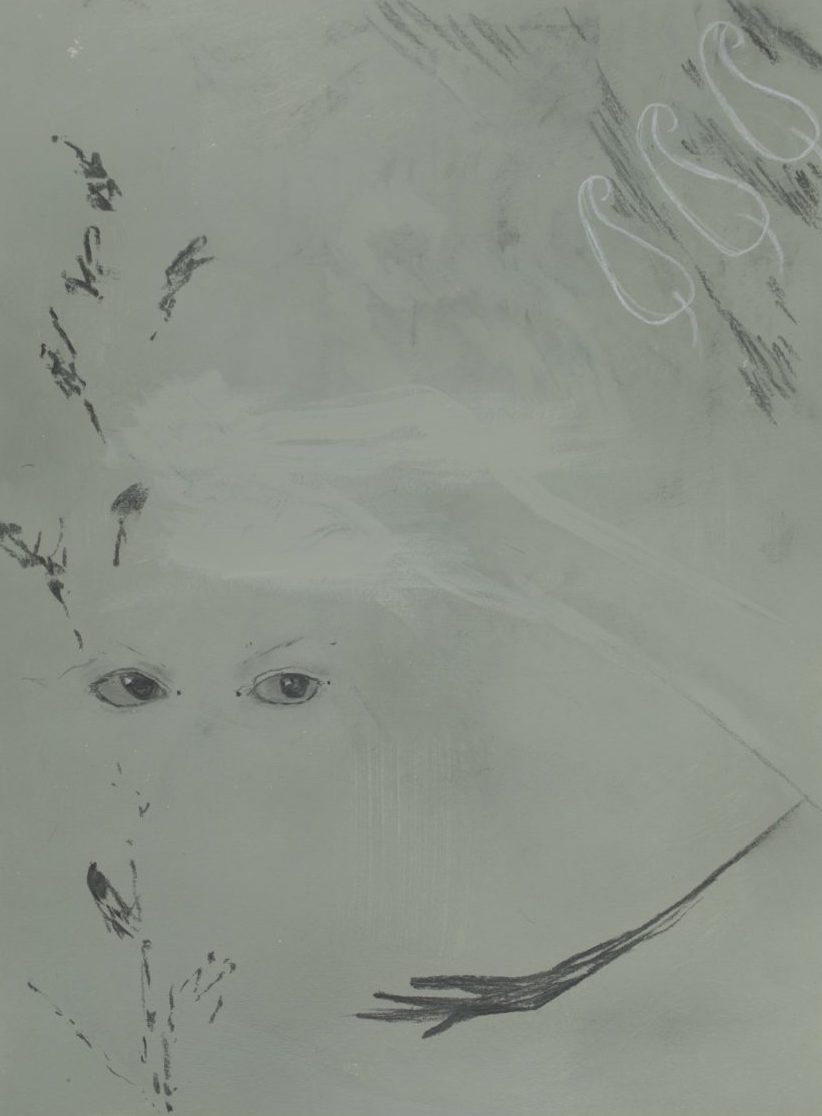

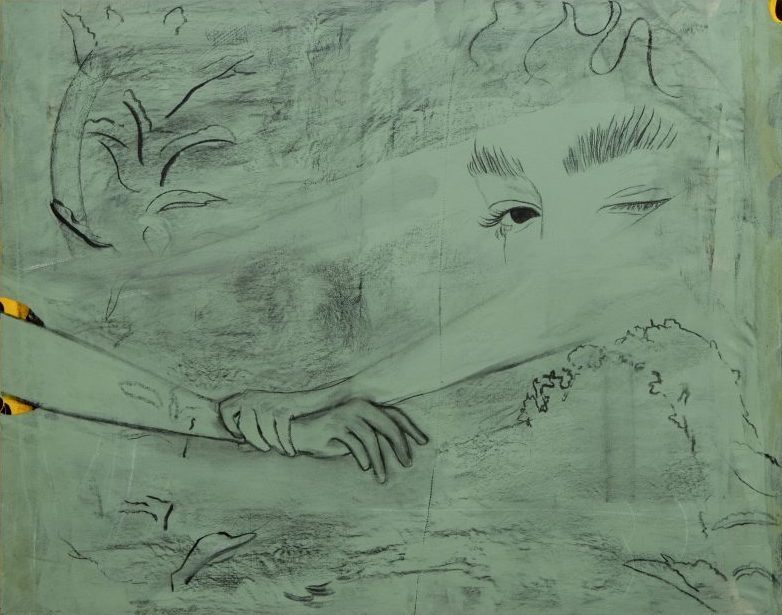

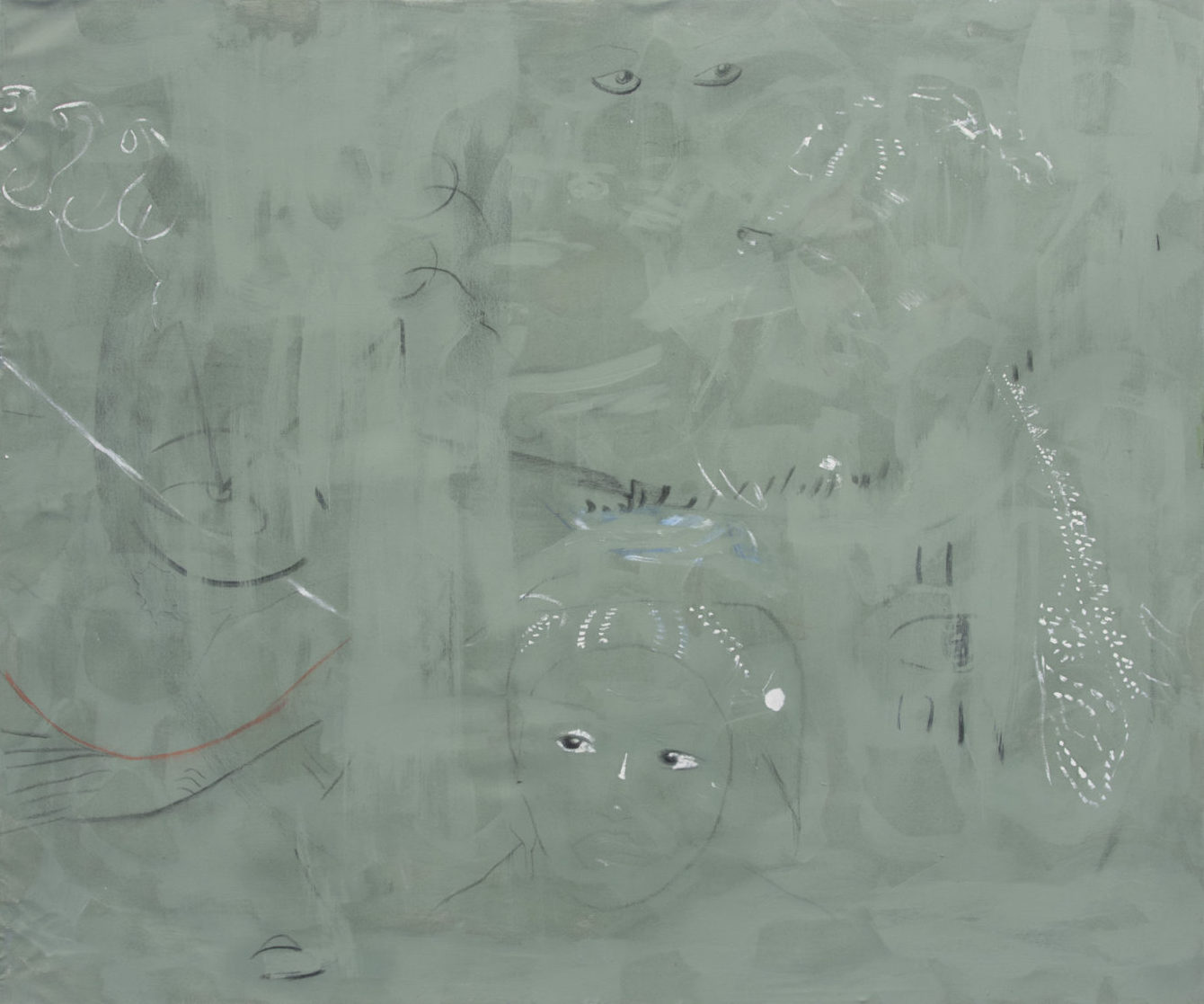

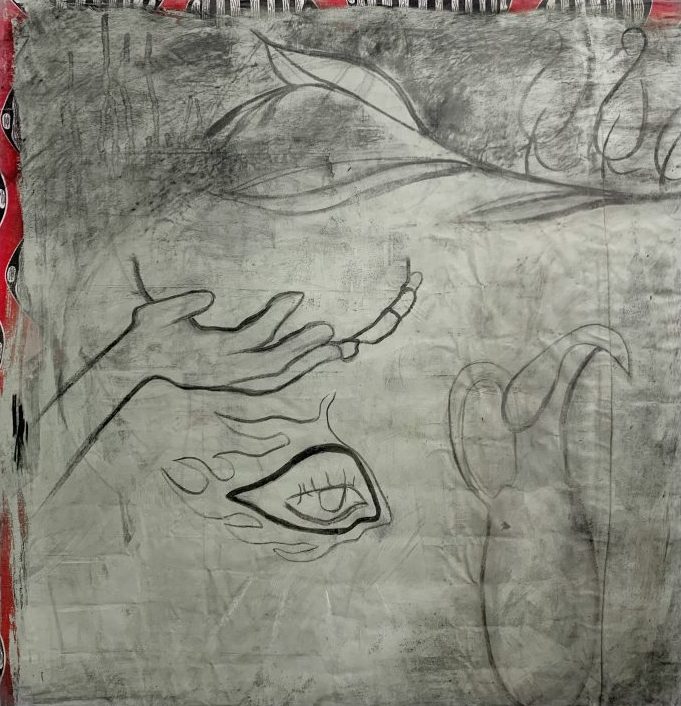

Saleh’s paintings articulate something about the ever-shifting nature of human relationships. It is captured in the fleeting gestures that sweep across calming shades of muted green. “I’m conscious of the energy that colours carry,” Saleh tells me. It is also in the history woven through the patterned fabrics that form the basis of her paintings and peek through the paint in brilliant colour. With a collage-like approach, she draws on imagery and music of personal importance, examining how people and perspectives come together, move apart and connect across space and time, in something like a choreography of a community.

In a moment where the term is often used as a buzzword, Saleh puts her commitment to community into practice with Muslim Sisterhood, which she founded with Lamisa Khan and Sara Gulamali in 2017. The collective have been celebrated for their workshops and zine that aim to provide a nurturing creative space for Muslim womxn and non-binary people.

Your drawings and paintings often contain fragments of bodies, such as eyes and hands. How do you see these elements or motifs working in the paintings?

My drawings are inspired largely by VHS home footage, leading to a tendency for me to work in a fast way capturing the moments that strike me the most. The paintings are a translation of this rich source of footage; whether it’s a video of my dancing shadow, a shy glance directed at the cameraman caught off-guard, or a bride side-eyeing an aunty at her wedding party who is (quite frankly) overdoing it. In this process of unearthing and translating, my paintings end up as a pictorial conversation between whatever is most prominent in that particular moment: both within myself and the archive.

“These types of small, seemingly innocuous everyday actions (a glance here, a movement there) reject profoundly the rigidity of a single story”

I don’t necessarily seek to portray messages in each of my paintings but I do find that fragments of bodies (especially eyes and hands) often convey so much feeling without the need for speech. Something is instantly recognisable. These types of small, seemingly innocuous everyday actions (a glance here, a movement there) reject profoundly the rigidity of a single story, since so much is left to interpretation. I don’t see these as motifs as they exist in their own right, although I do recognise that my work does, inadvertently but also contextually, exist within the larger idea of returning the gaze. This is something I really like because being able to take control of perspective is significant for me, and I see how this works within my paintings through the prominence of eyes. However, I am happy for the drawings to continue being ambiguous and open to interpretation. Painting lends itself to the multiplicity of reading and stories. Ultimately, this is what interests me.

Digital photography, video and painting come together in your work in an exciting, candid way. How would you describe your working process?

I have a studio-based practice and will often structure studio days into my week so that I can spend a whole day there working on paintings. Normally, I make drawings based on video footage as a starting point. My paintings then take ideas from these sketches to create something new. When I start a painting it begins with thin cotton fabric or a canvas that I often paint an earthy green before drawing on top with charcoal. I often use fabric I’ve found at home that is no longer needed, not only because it’s sustainable to do this but because I cherish the personal history that these fabrics hold. I decide the scale and use a sewing machine to combine and reconfigure different fabric patterns to form the base. I also love having friends over at my studio; being around them in this space, either listening to music together or hearing their perspectives, is an affirming part of the process.

What are your inspirations?

My paintings are informed, primarily, by the richness of the footage in my family VHS archive. I’m also a big fan of video artist Kahlil Joseph. I find his video work to be incredibly moving and beautifully shot (for instance, m.A.A.d., 2014 was one of the first works in a gallery to make me cry). Lubaina Himid is inspiring, not just as a painter but as an individual too. She brought together a community of Black artists and really paved the way for this generation. Her dialogues surrounding the characters in her work is so brilliant. I have yet to see the Making Histories Visible archive in Preston that she leads but it is something that I have been longing to go to, and research more into.

I love music and often have something playing in my studio whilst I paint. At the moment, it’s a playlist I have been adding to during quarantine that consists of a mix of R&B and Dancehall music. Currently, my most played songs are Ojerime’s SWV—This Ain’t Easy and D’Angelo’s Send It On.

“It’s important for me to recognise what I have access to and how I can utilise it for the benefit of my community”

In 2017 you co-founded Muslim Sisterhood with Lamisa Khan and Sara Gulamali. What prompted you to set this up?

Muslim Sisterhood is a London-based artistic collective working within photography, fashion, publishing, and events. We host free workshops with the intention of creating inclusive safe spaces where we can express ourselves creatively and comfortably while centring the experience of Muslim womxn and non-binary Muslims. Workshops have included Dkhoon (incense) making, zine making, self-defence, belly dancing and tile glazing classes. This work is fuelled by the desire to unite our community.

When I co-founded Muslim Sisterhood it was fundamentally about leveraging the resources and privileges that I had access to as a result of being at art school. I utilised the photography studio at Slade for our shoots. I also made use of the media equipment and software for work that I did as the media officer for the UCL Somali Society. It’s important for me to recognise what I have access to and how I can utilise it for the benefit of my community. This sort of praxis is critical because it puts the idea of community care into much-needed practice via direct action.

Blue, 2018

We also just really liked each other before setting up Muslim Sisterhood. We felt a collective disconnect between what was already out there representing Muslim womxn and decided to create something to fill that. If you want there to be a space, you have to go out there and create it yourself. Our debut zine is stocked at ICA London and this year we are so pleased to be featured in the 2020 Dazed100 line-up!

Have your personal practice and your work in Muslim Sisterhood had an effect on each other?

The community work and workshops we’ve run have had a profound impact on me and that, in turn, has impacted my studio-based practice quite a bit. The feeling of being held by my community through my work in Muslim Sisterhood has helped by making me feel much more free to paint whatever I want, without restrictions or fear. Coming from a Fine Art background, the visuals that come through Muslim Sisterhood are super important to me. I see my work as interdisciplinary; consisting of a studio-based practice and a community-building element that inform each other and are intimately intertwined.