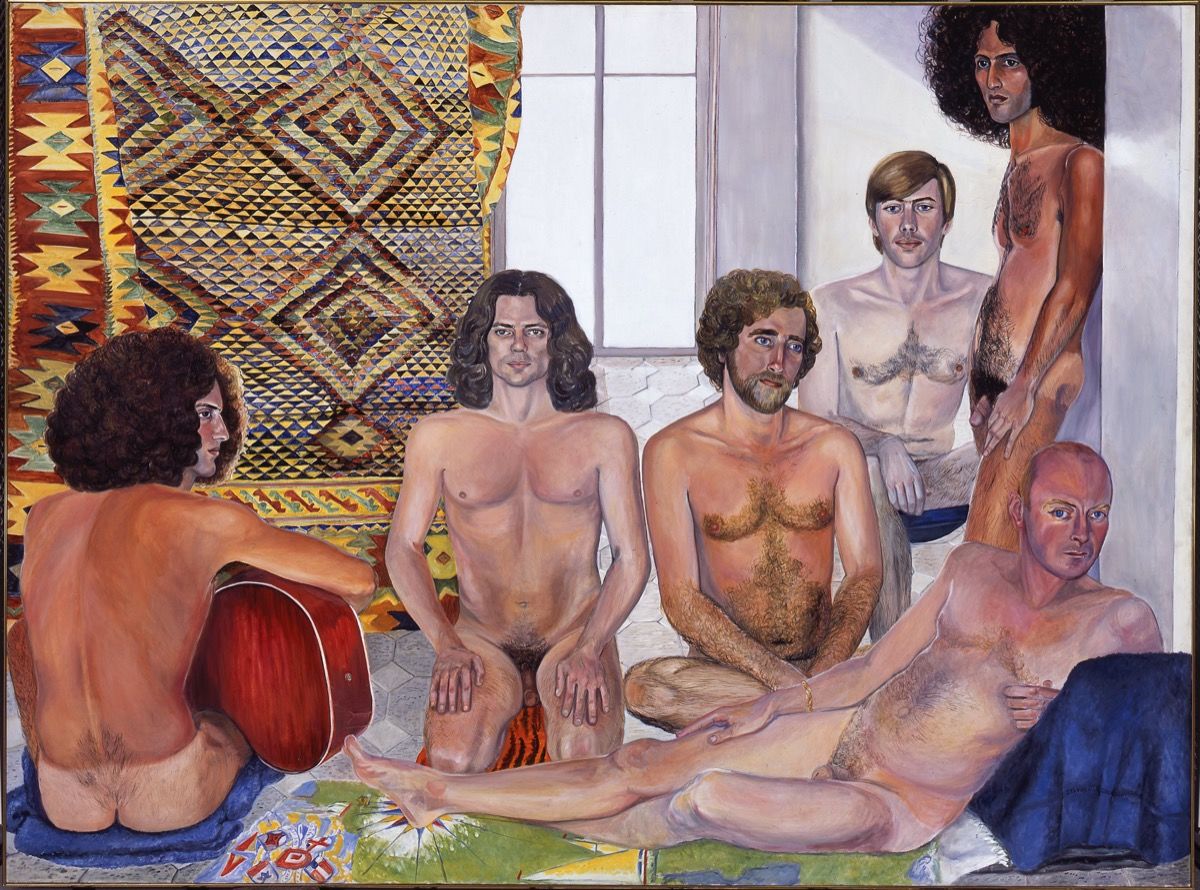

At The Turkish Bath, 1976. Collection of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Courtesy of the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

When the Welsh-born painter Sylvia Sleigh began painting her explicit male nudes in the 1960s, she was consciously subverting the long-established tradition of female nude figures in the history of art. “I don’t see why male genitals are more sacred than female,” the Welsh-born artist once said.

Sleigh, who was a member of the iconic all-women A.I.R gallery (she painted a group portrait of the members in 1977) and set up her own space to support women artists in SoHo, first turned her painterly gaze on the men in her own life: she depicted her second husband, the famous art critic and Guggenheim curator Lawrence Alloway, in more than thirty works, and other muses came from their circle of artistic friends—including Nancy Spero and Leon Golub’s son, Philip. Knowing her subjects intimately was a statement about perspective and looking and an important part of her painting practice. In a 2008 interview with Lynn Hershmann-Leeson, she said that she “wanted to paint men in a way that I appreciated them, as dignified and intelligent and nice people”.

“With or without their clothes, Sleigh ‘was aiming to remove objectification, not desire, from art’”

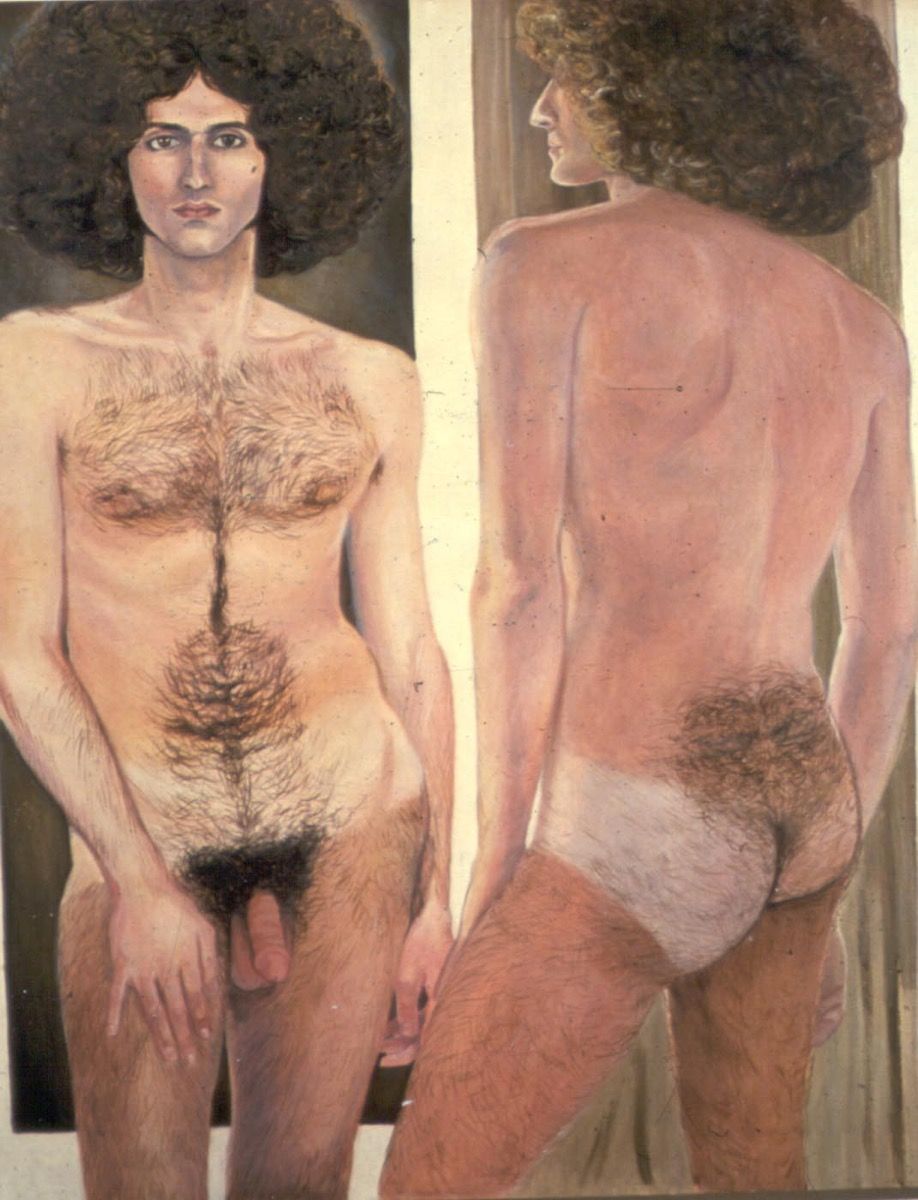

One of those people was Paul Rosano, a young musician moonlighting as a life model at New York City art schools in the early seventies. Rosano met Sleigh by chance when they were both called to fill in at an art workshop. Rosano would become one of Sleigh’s most frequent subjects, and features in her famous Double Image: Paul Rosano, a 1974 nude portrait that stirred controversy when exhibited at the time. In the painting, Rosano is shown from the front and back, hirsute, slender and poised. Many of the painting’s closely-observed details—the tan lines, the body hair—were intended to make her subject more human and real.

“She told me she felt she had to engage her models in conversations to learn more about them,” Rosano recalls. During their sessions, he said, they would talk continuously about art, music and life. “In that way, she could paint them better, she said, drawing out their character so to speak. It was of the utmost importance. She said she could better present them on canvas if she knew her models as well as she could and even better if they shared a certain simpatico.”

Painting her subjects in the intimate, comfortable setting of her own home also created the special atmosphere in Sleigh’s work. The first time Rosano sat for her, “we began working in her sitting room, which was quite beautiful with faux Italian tiles, floor to ceiling windows, quite high, looking out on her lush garden, which she tended, a few fine pieces of antique furniture and some of her paintings and works of other artists hanging on the walls.” Over the next three years, Rosano would visit Sleigh’s studio three or four times a week to sit for her, and they became close friends. Rosano features in twenty-five paintings. “She simply said I was her type: southern Mediterranean features, aquiline nose, and long hair.”

Sylvia Sleigh, Double Image: Paul Rosano, 1974. Courtesy of the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

The unusually tender gaze exchanged between Sleigh and her sitters is just as palpable in her earlier portraits of women, both clothed and nude. Included in a current Hauser & Wirth exhibition is a 1964 portrait of the artist Suzi Gablik and Triple Portrait of Sylvia Castro-Cid, 1966, depicting the wife of Chilean artist Enrique Castro-Cid—both women that Sleigh knew and admired.

With or without their clothes, Sleigh “was aiming to remove objectification, not desire, from art”, explains Laura Bechter, curator of The Ursula Hauser Collection and co-curator of the exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Unconscious Landscapes, which features a room dedicated to portraits by Sleigh. While this was a radical proposition at the time, Sleigh’s ideas about her male nudes were unpopular with feminists, and her figurative stance was unfashionable in the art world in the 1970s.

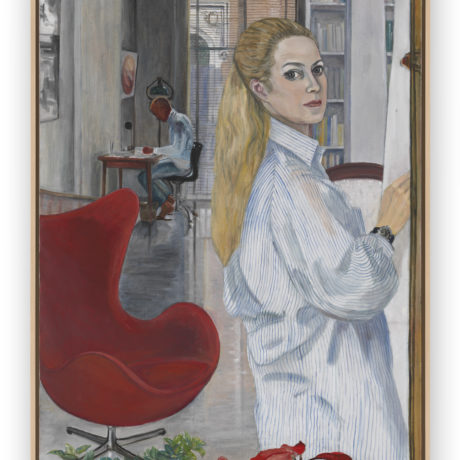

“Although she was socializing with many artists and thinkers at the centre of the art world in the 1960s, Sylvia Sleigh’s work didn’t follow the fashion of the time, she wasn’t afraid to be individual. Her work didn’t represent the zeitgeist, her depictions of her friends provide an interesting snapshot of this moment in art history,” Bechter says. Ursula Hauser was one of the major collectors who supported Sleigh’s work, but they only met when Sleigh was already in her nineties. After Sleigh passed away in 2010, at ninety-four, Hauser purchased the Chelsea townhouse that also served as Sleigh’s studio, restoring the patterned wallpaper, and a mirror that appears in a self-portrait from 1969, Working at Home—also on show in Somerset until September.

“Her work didn’t represent the zeitgeist, her depictions of her friends provide an interesting snapshot of this moment in art history”

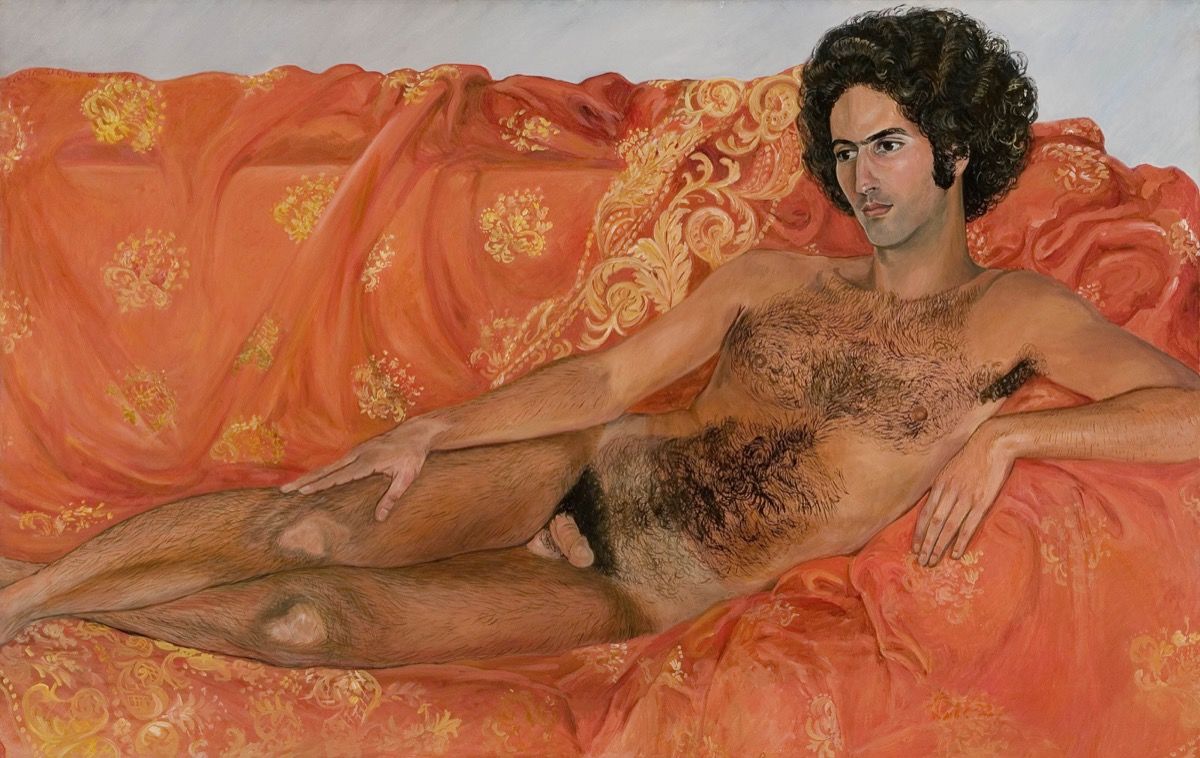

The first portrait Sleigh painted of Rosano was Paul Rosano Seated—in which her muse sits in an Eames Chair. Rosano said Sleigh used her models’ names intentionally, both as a personal tribute and sign of respect for their individuality. Rosano also features in Imperial Nude—a reference to historic nude paintings.

It may not have been appreciated as an effective feminist strategy at the time, but five decades on, few other female artists have attempted to paint male nudes in such an intimate and humane way, embracing the erotic while treating male bodies with dignity and respect—something that is missing in centuries of anonymous nudes, both male and female.

Unconscious Landscape: Works from the Ursula Hauser Collection

Until 8 September at Hauser and Wirth Somerset

VISIT WEBSITE