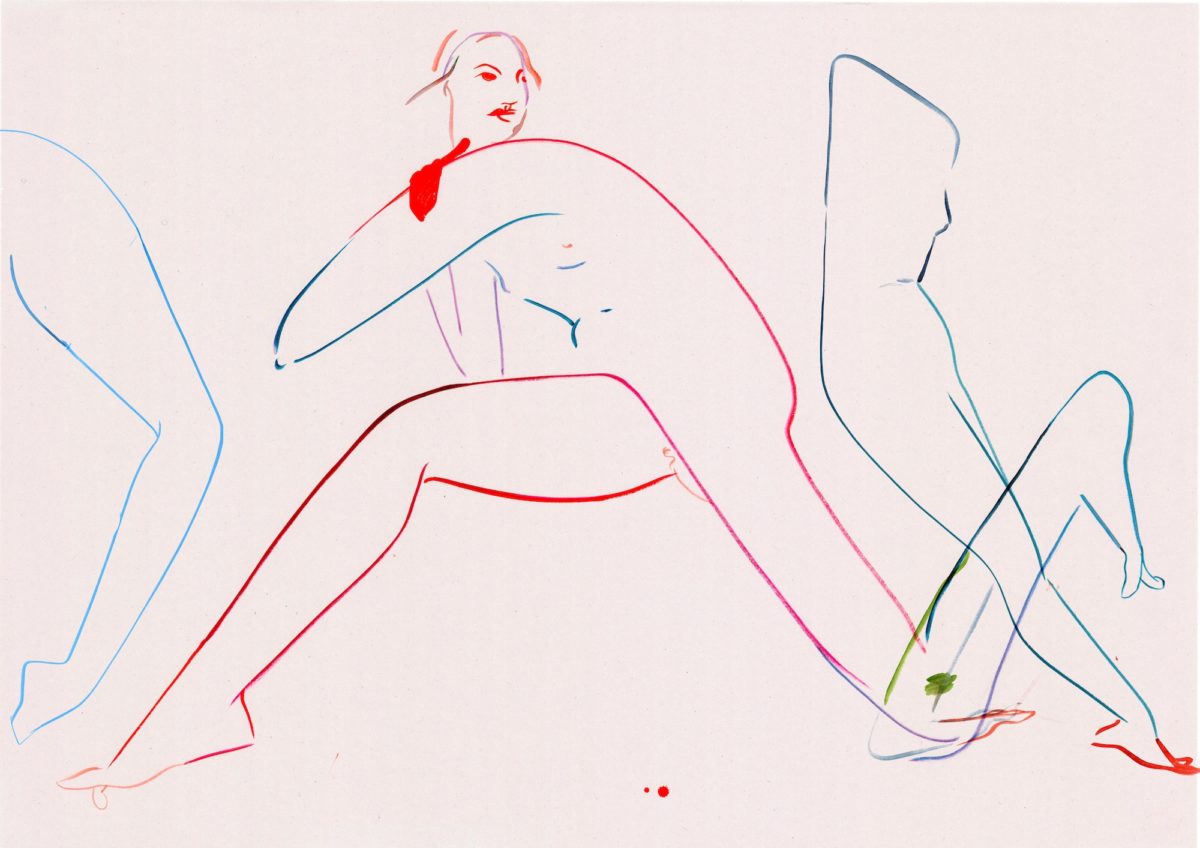

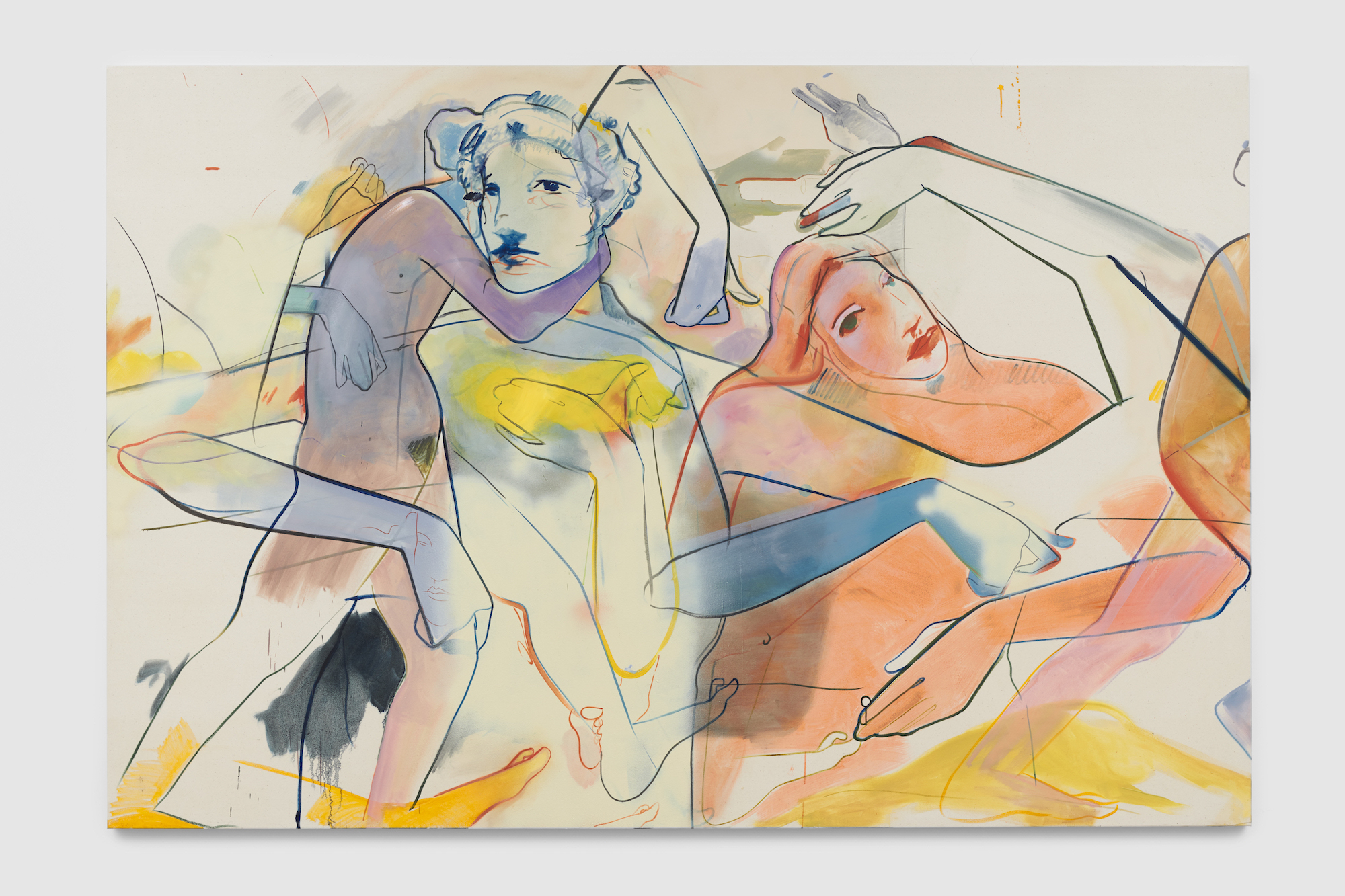

Drawing is one of the most intimate and immediate of instincts. In childhood, it is one of the earliest outlets for expression that we have; even before we learn to write, we scrawl and sketch. France-Lise McGurn extends this impulse in her free-flowing, expressive drawings of languid men and women. These fluid figures are rendered in pastels, spray paint and markers, McGurn’s gestural lines hinting at lives and loves unknown as their bodies tumble and fall. Her mark-making leaves space for suggestion, the blank section of her canvas an invitation to imagine; she leaves her viewers to fill in the gaps.

There is a visceral quality to McGurn’s work, as if the lines were drawn swiftly; with urgency. It follows that they rarely stay within the confines of the canvas. Instead, restless lines extend across entire walls, as if their subjects were leaping towards something beyond the gallery. Her expansive yet intimate paintings has garnered McGurn growing acclaim, and she has a busy year ahead of her. In January alone, she will open two exhibitions; one at Simon Lee Gallery in London, and the other at Tramway in her hometown of Glasgow, where is now based. She is also set to participate in Glasgow International in May 2020, an opportunity to connect her own memories of growing up in the city with her ongoing, wandering path as an artist.

What is your relationship to drawing, and how did you first arrive at it and begin to incorporate it into your work as an artist?

I think that it’s always been a part of me. I went up to Dundee recently, where I studied, and remembered that my degree show was not so far away from what I still do now. Lots of sketchbooks; papering all over the walls… I think it’s about that immediacy. Drawing is the quickest and most instantaneous route into something. I’ve always been really drawn to these ephemeral elements: notes and love letters; they reflect the very second that their creators thought of it, the second that it came into their brain. It’s such an energy, to create something so ephemeral and not too laboured. The drawn line is how I can get that quickness; speed is really important to me, and I work very quickly. If I have to labour on something, it kind of kills it.

It’s also about being attracted to drawn works by other artists. I don’t work directly from anything, but the materials that I do collect are often printed matter: flyers, magazines, illustration. I love Peter Doig’s cinema project; he created handmade cinema posters, and it’s very different to other works by him. You’re so close to an artist with works like that. There’s nothing to hide; it’s had to come from a really instinctual place, and I’m really drawn to that. Looking at a lot of illustrative work recently, I was thinking about Nell Brinkley, and this period of illustration where artists would really develop their own archetype—they would have the Brinkley Girl, for example, where the drawn figure becomes an archetype.

“Drawing is the quickest and most instantaneous route in. I’ve always been really drawn to these ephemeral elements: notes and love letters”

How much of a specific character do you imbue each of your fluid male and female figures with? How much do you imagine for them, and who are they?

It’s very deeply figurative work, but I see the figures as an embodiment of one idea; one emotion; one archetype. They are recognisable forms; you recognise the shapes, but it’s not narrative. It’s not a portrait of anyone, it’s not anything specific. I spoke to someone once who said that the faces are very blank. There’s not anguish, there’s nothing readable, and that relates to how I view them. But also, I studied in Florence (I was just out of art school, twenty years-old) and there is a relationship to antiquity there too, where figures will often represent religion or, say, the Holy Spirit. With my figures, you’re not so much drawn to one individual image and there’s more of a flow. It’s like when you are in a crowd, and it’s not about one single figure. How do you feel this familiarity, understand that there’s these figures around you, but not be picking out the story of one person?

I used to compare it to the feeling of being in a club environment as opposed to being at a gig. It’s a relationship to ecstatic thought, being in your body with bodies around you; it’s about the mass. But now that I have a one-year-old, I have a different relationship to it. With Sleepless, my exhibition at Tate Britain last year, it became more about being in a city. It was about city living, and releasing very suddenly that, when you’re in your bed, you’re surrounded by other people who are also in their bed. This feeling of being coddled in, and then realising that others are all around you. I used to collaborate, painting dance floors in Glasgow nightclubs; we did an opening at 3am once. Stuff like that, it’s always been in my work. It’s not that I don’t relate to traditional figurative work, where it’s all about the subject, but mine is about misplacing that.

Your work frequently spreads further than the canvas, taking in architectural and design elements. Why is this, and what interests you about pushing to the space beyond the frame?

There are a few reasons why it makes so much sense to me to work directly onto walls or the fabric of the building. There was a massive influence from my mum, who had a job and was an artist as well. She turned our house into a complete artwork. She would paint on the walls, or create chandeliers, so it just never occurred to me to not paint on the walls. I came to painting on canvas very late, and I found that rigid form and shape of it very restrictive. I’m interested in this ephemeral, quick, animated drawing, and I just couldn’t get over it. Once I realised that I was allowed to keep both the canvas and the wall, and not just work on the easel, I felt happy. I started making these framed works, but it was the same, and I would onto the glass and onto the frame, too.

It’s about breaking off from the canvas if I can, but the type of space that the work occupies also really affects it. Sometimes I’ve done the drawing and felt it’s not working, but then someone walks through the space, and suddenly, it feels right. I did a domestic space at the artist residency programme in Hospitalfield, Arbroath, and it really changed the details of the work. There were shutters that could be opened and closed, and I knew people would be sitting in there, studying in it. How it’s going to be used changes it, particularly compared to a gallery where people will be more in and out.

How has your experience as a new mother influenced your work, both in a thematic way and a practical one?

I have a running interest in female archetypes, and I think that archetypes shift. You go from archetype to archetype; I’m getting older and my sexuality is changing. As you shift yourself, that’s interesting—I’m not collecting as many club flyers as I used to, for example, and the subject matter shifts with that. Motherhood also affects things in a really simple way, in terms of the time that you have, and the momentum that you have when you’re working. There never used to be anything as important as art, but there are different levels of deepness of my love now because I also want to spend time with my daughter. Also, I have included some babies in the corner of paintings, but it’s not as directly autobiographical as that. It’s all part of a bigger trajectory, and I suppose a lot of my influence came from my mother, and now I have a daughter, so it feels like a continuation. It is affecting my work in a really personal way.

“It’s a relationship to ecstatic thought, being in your body with bodies around you; it’s about the mass”

You’ve got a lot coming up next year, with solo exhibitions at Simon Lee Gallery in London, Tramway, and your participation in Glasgow International. What are the threads tying these shows together, and what are you excited to see in the development of your work?

Tramway and the Simon Lee shows open six days apart; they’re so close. I thought, either these need to be really different, or they’re two different types of the same beast. They are called In Emotia and Percussia. The titles are connected—I think they are like two Siamese cats’ names. They’re really connected but also different. In Emotia in Glasgow is more influenced by the fact that I’m from Glasgow. I’m working on a neon for it, following one that I did for Glasgow institution Nice N Sleazy, so it’s got connections to Glasgow nightlife; I was thinking, it’s winter, it will be dark and cold, this is something that will glow from inside. I’m also doing wall paintings there; instead of having canvases and wall paintings in direct relationship, it’s going to be mainly wall paintings. All singing, all dancing!

The one in London is more of a painting show, lots of canvases, and I am doing a wall drawing there to animate it. The titles are both made-up words that sound like something that you might know; Percussia to me suggests a drum or rhythm—it has a pulse but is more sensual. They’ll be quite different, but I’m working on them at the same time. And then, Glasgow International is a totally different show altogether. It’s in an unusual space for me, in a museum, so I can’t do wall drawings, but I’m still experimenting for it. I’m from Glasgow but I haven’t ever really shown here before, and Kelvingrove is probably one of the first places that I ever saw paintings as a little girl. It will be very special.

France-Lise McGurn, Percussia

At Simon Lee Gallery London 24 January to 22 February 2020

VISIT WEBSITE