Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

Out today on Artsy is Odili Donald Odita on Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color.

I don’t know what it was about Alessandro that meant he got under my skin. He wasn’t the only Italian man that I would be involved with that year, and he hadn’t seemed like the sort that I would lose my head over. I met him on a couch surfing website when I first moved to Italy, and it turned out we were attending the same university. He was training to be an architect; I was on my Erasmus year.

We became, ostensibly, friends. Like almost every Italian man I met, he had a girlfriend back at home, waiting for him. He was a keen photographer of female beauty, and much of his online output consisted of images his blonde fidanzata looking pretty and moody in monochrome. I would spend a sizeable chunk of my dongle’s measly data allocation obsessing over these images.

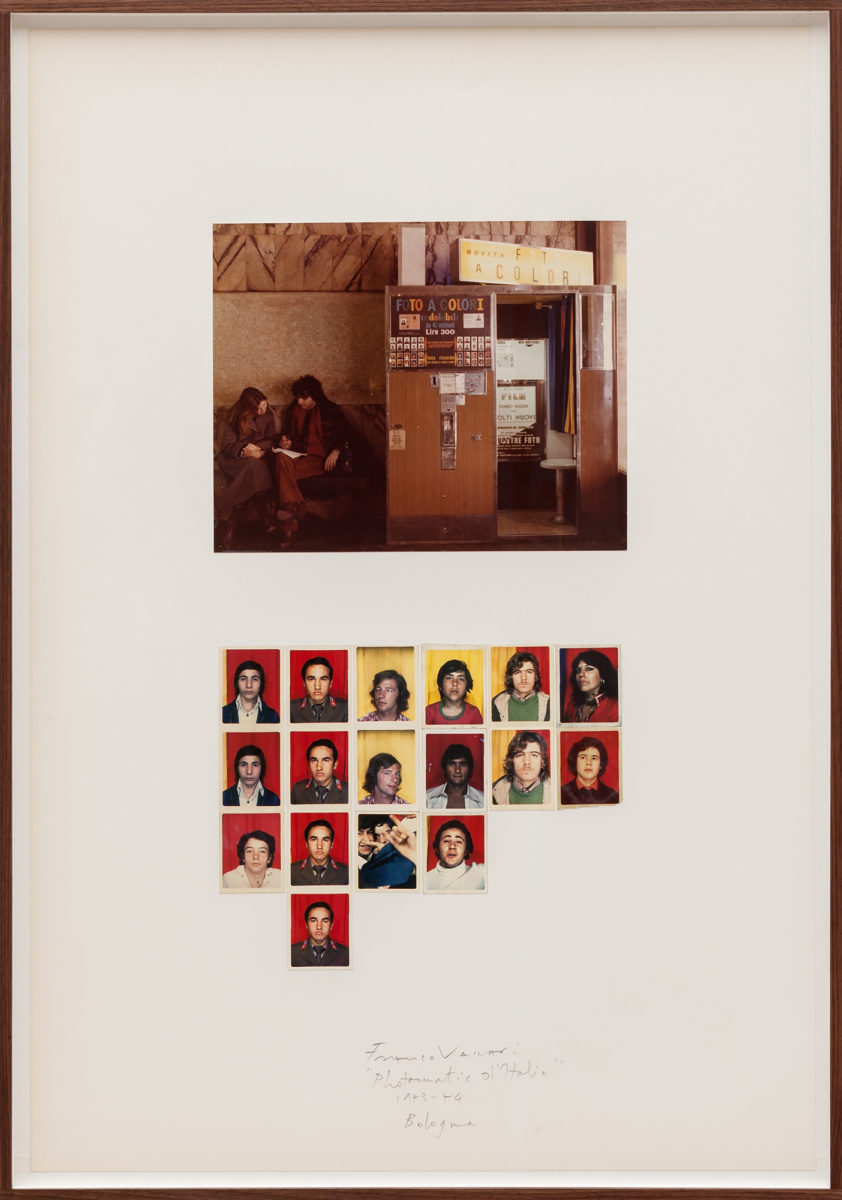

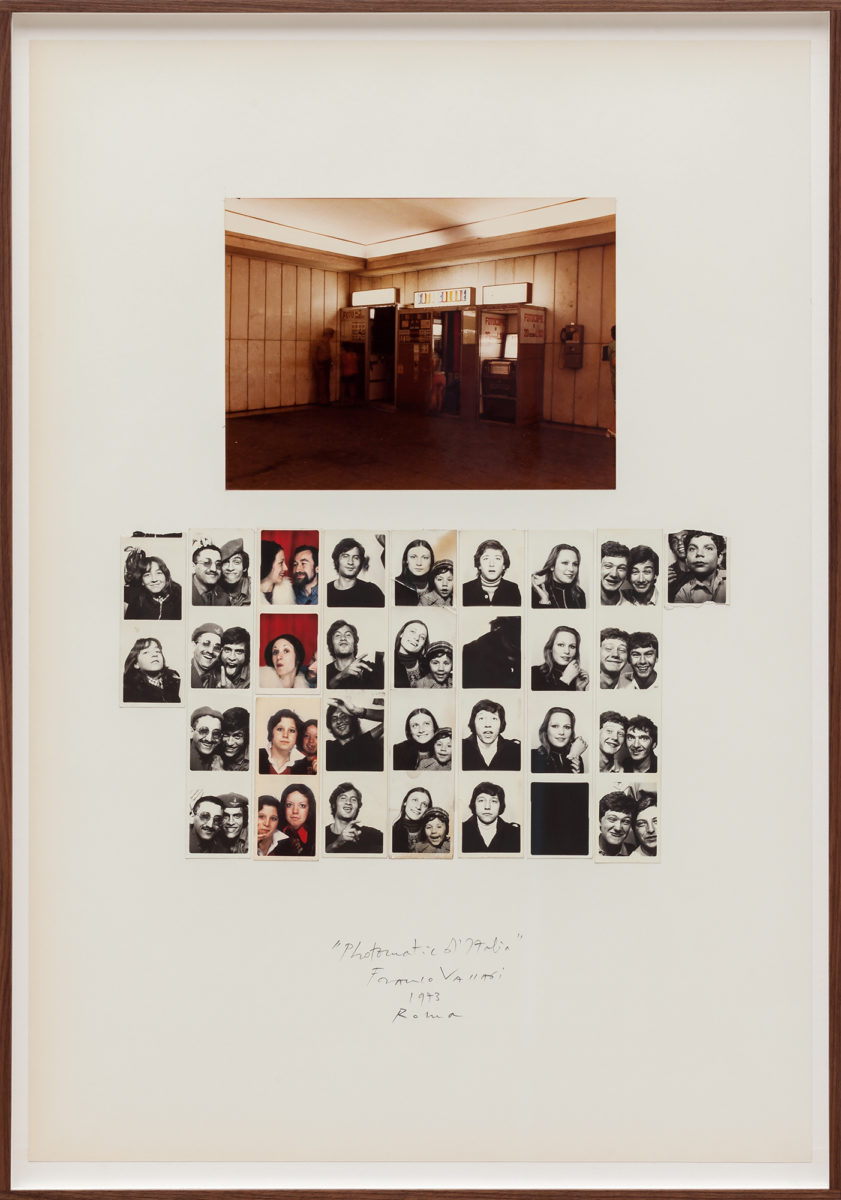

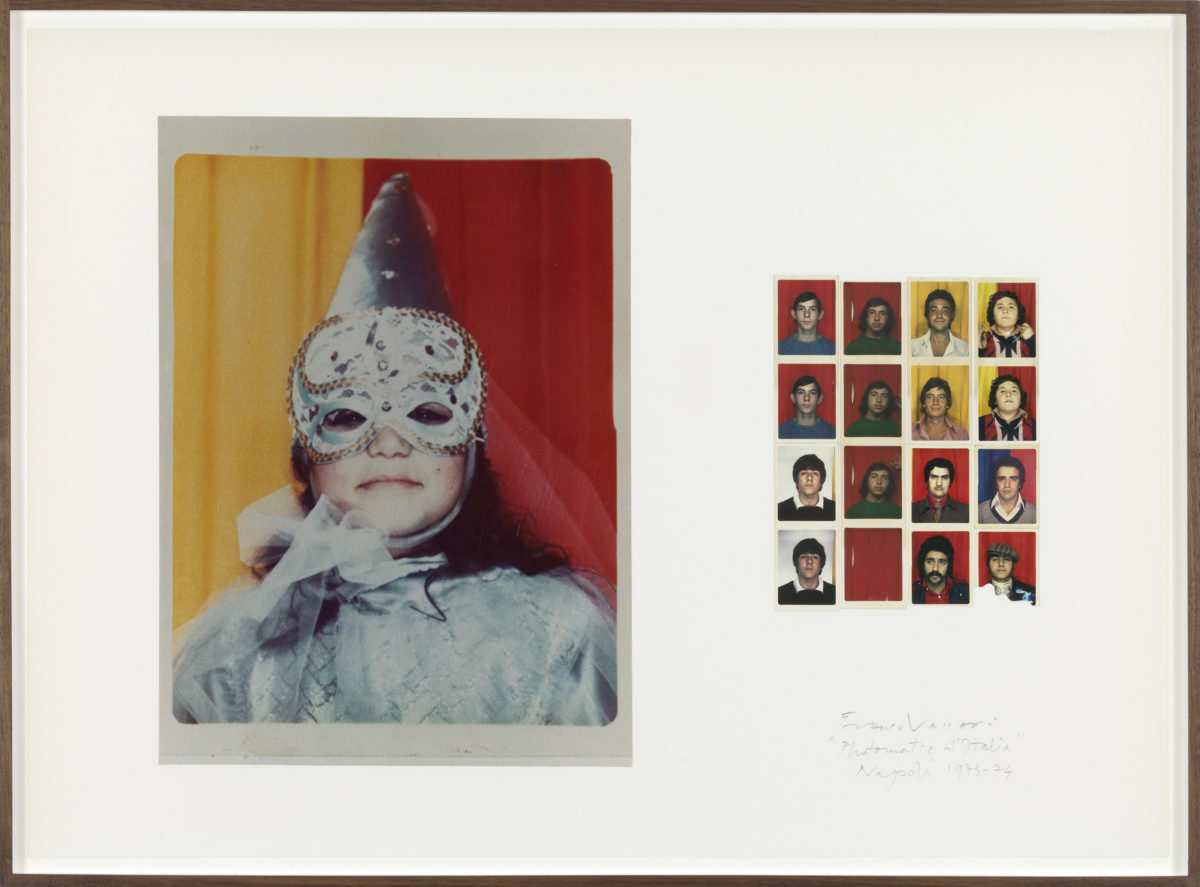

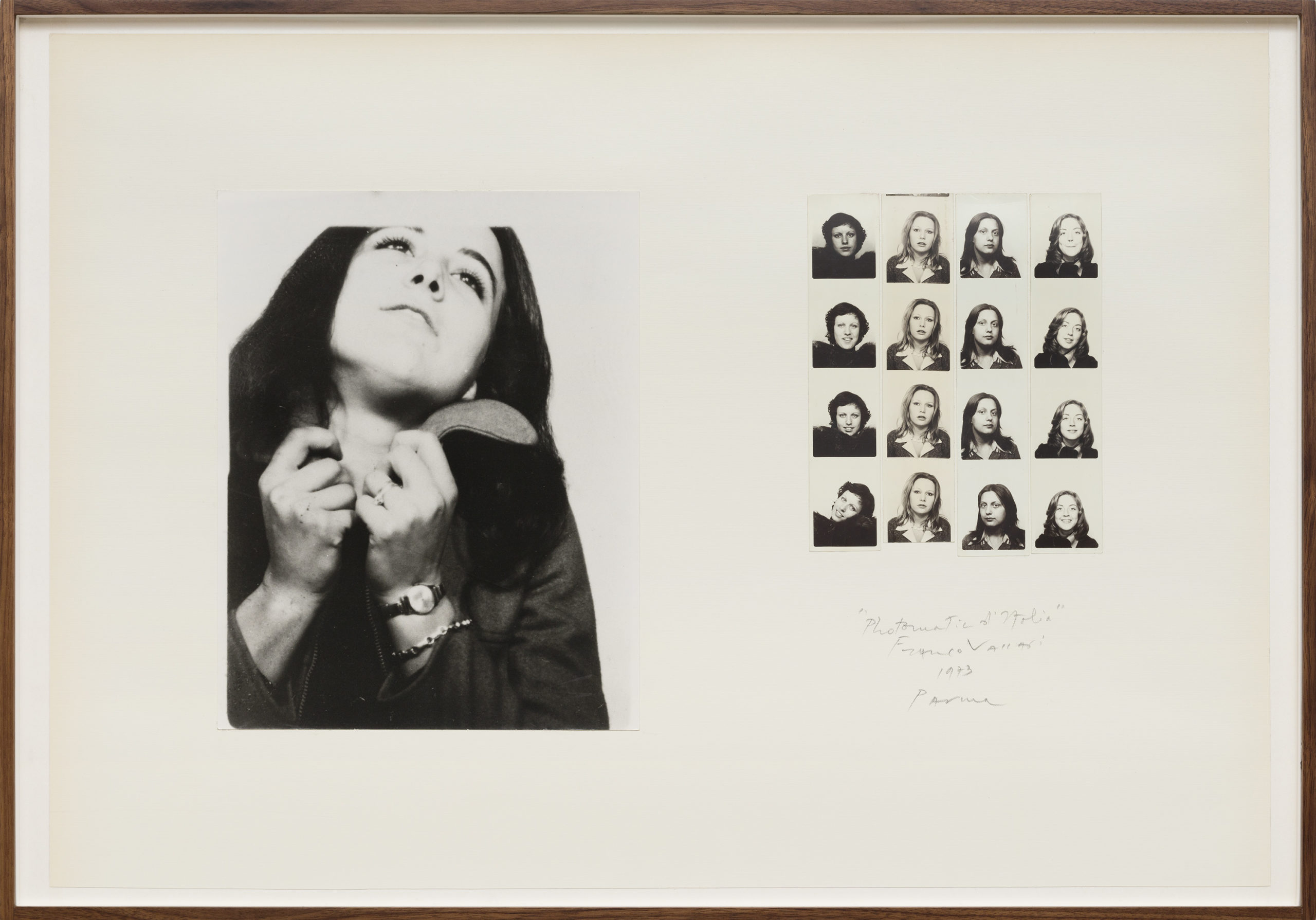

- Photomatic d’Italia (Roma), 1973-74 (left); Photomatic d’Italia, 1973-74 (right). Both courtesy the artist and P420, Bologna

“Selfie culture was still in its infancy, and a photo booth portrait (scanned and uploaded, naturally) made a statement” online pharmacy order cialis-soft no prescription with best prices today in the USA

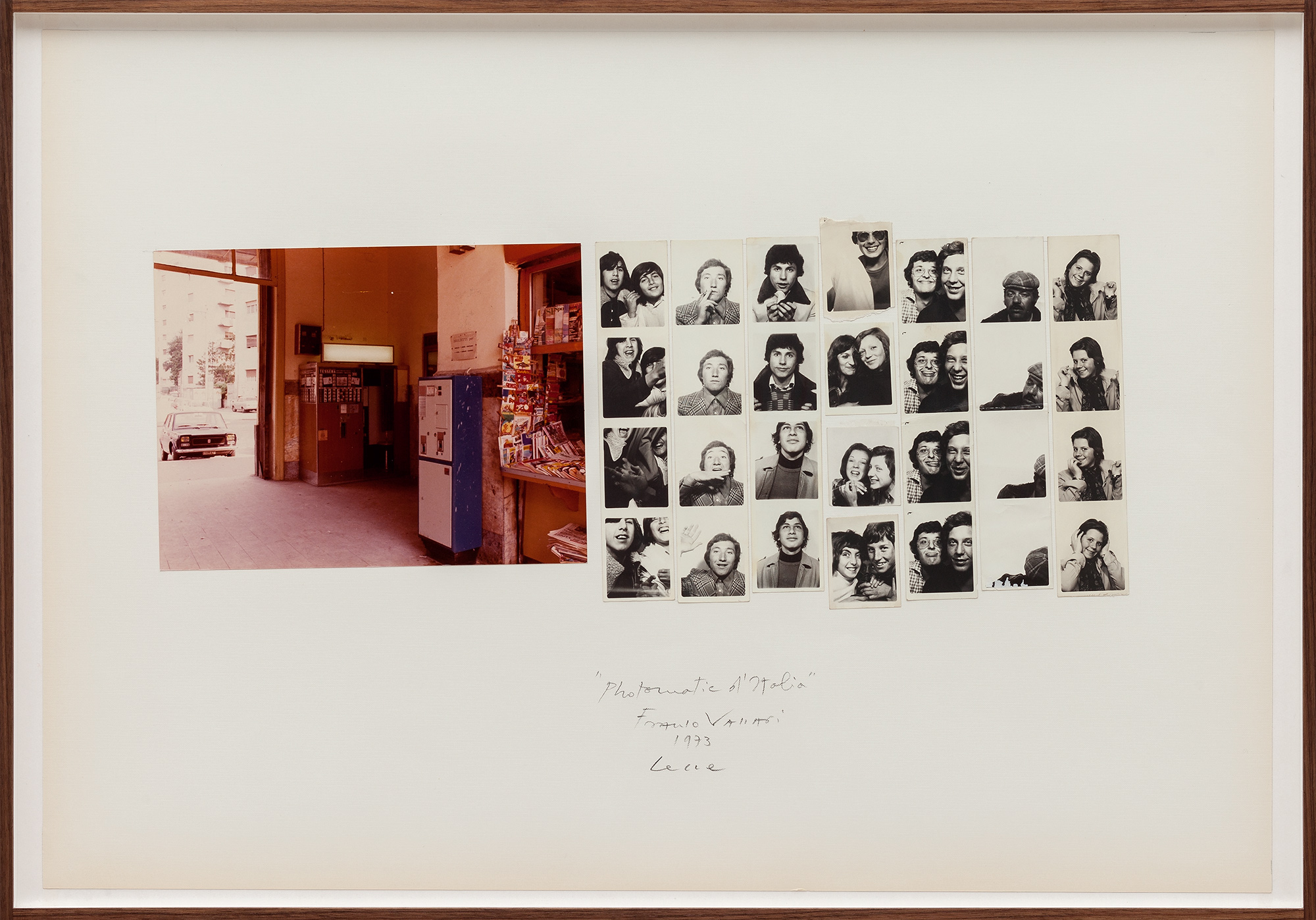

I was taking a number of Italian and art courses, and it was in one of these that I came across the work of Franco Vaccari. We had to submit a final project whose theoretical underpinnings were rooted in the work of an artist. I chose Vaccari, whose 1972 Venice Biennale project Photomatic d’Italia made pioneering use of the photo booth in contemporary artistic practice. In asking visitors to take and contribute their own photographs, he ended up with over 40,000 self-portraits, resulting in a collaborative, democratic artwork that examined questions of inclusivity and citizenship and foreshadowed the rise of online crowdsourcing.

Vaccari asked visitors to “Leave on the walls a photographic trace of your fleeting visit.” For my own project, I planned to lift this idea and ask friends that I had met during my year in Italy to submit a strip of self-portraits, which I would then use to compile an album of memories. It was not an original concept, but then originality didn’t seem to be a criterion for a decent grade. My tutor loved it and I was on course for an excellent mark.

To an extent, I fetishised the aesthetic of the photo booth with a hipsterish nostalgia that was characteristic then. I was a member of the “bridge generation”; we were raised analogue, then went digital. We instinctively understood both worlds. At the time, selfie culture was still in its infancy, and a photo booth portrait (scanned and uploaded, naturally) made a statement; it implied a level of detachment from the mass-produced modes of digital image production. Crucially, it gave off a cool aura of the sort I wanted to project to Alessandro, to whom I chatted online every single night.

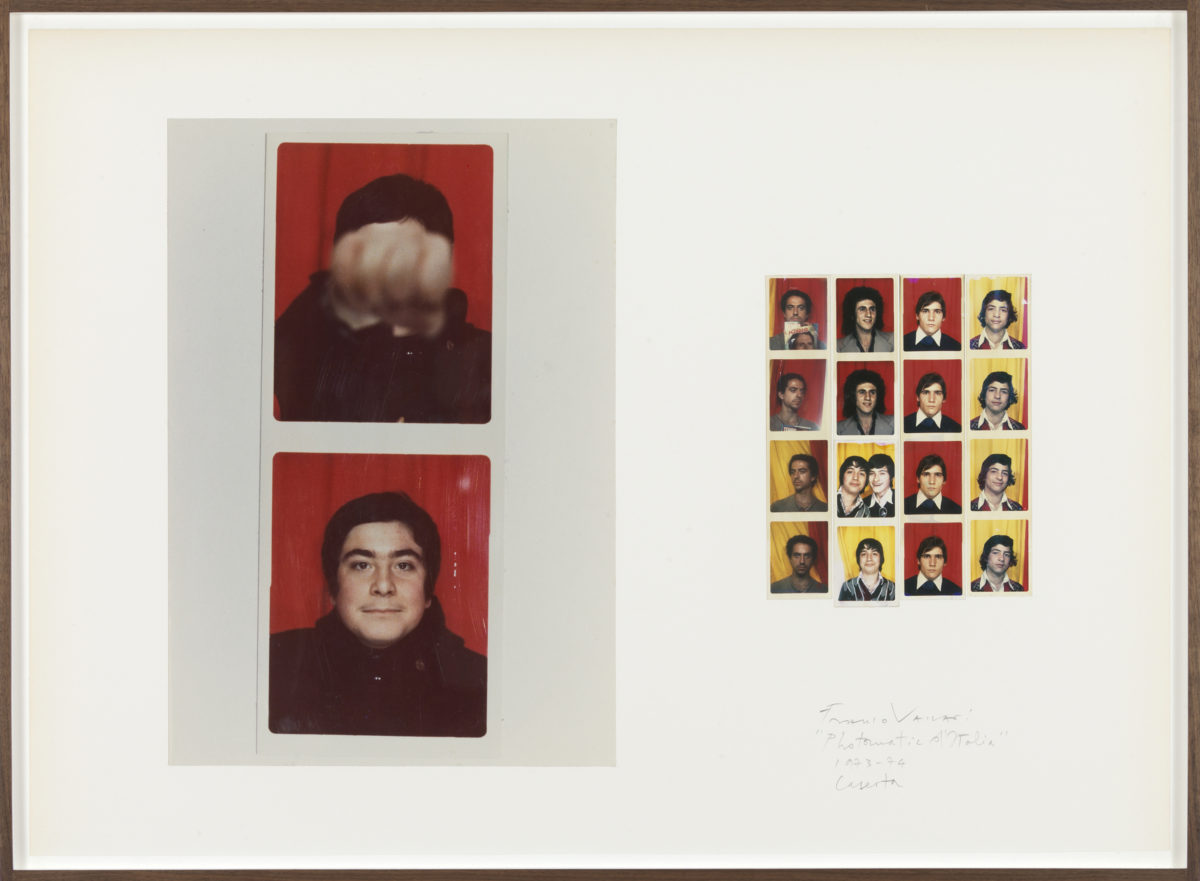

Photomatic d’Italia (Lecce), 1973. Courtesy the artist and P420, Bologna

He would tell me about all the other women he was sleeping with and ask me for advice when they got too clingy. Alessandro was gifted at flirting just enough that it would pique your interest before he withdrew. While having coffee he would reach out and momentarily touch your hand, or he would tuck a piece of hair behind your ear as you sat eating the risotto he had cooked for you. Sometimes he would engineer it so that you were standing very close, and then he would be looking down towards your upturned face as you stood on some autumnal street, and you would think, “This is it…”

If any of this is ringing alarm bells, please remember that I was young, alone in a foreign country and craving human connection. Perhaps the sex, when it finally happened, was disappointing because the level of chemistry leading up to it had been so intense. It did nothing, however, to abate the infatuation. On some level I knew that I was being played, that Alessandro was toying with me in ways that would now see him labelled, in internet parlance, a “fuckboy”, but I didn’t care. I was in too deep. And so, towards the end of my year abroad, when he texted me the day before my project deadline to say that he was in A&E because he had dislocated his knee, I dropped everything.

It would be very late before I returned home, my heart completely broken. Looking back, I realise that I wasn’t crying because I was in love with him. I wanted only for him to see me, for me to be someone worthy of care and consideration too. I was crying for the sort of tenderness that I craved, and which felt impossible at that time in my life. I was crying because, when I finally took him home and helped him hobble up the many, many flights of stairs to his apartment, he turned at the threshold and said, simply: “You can go now.”

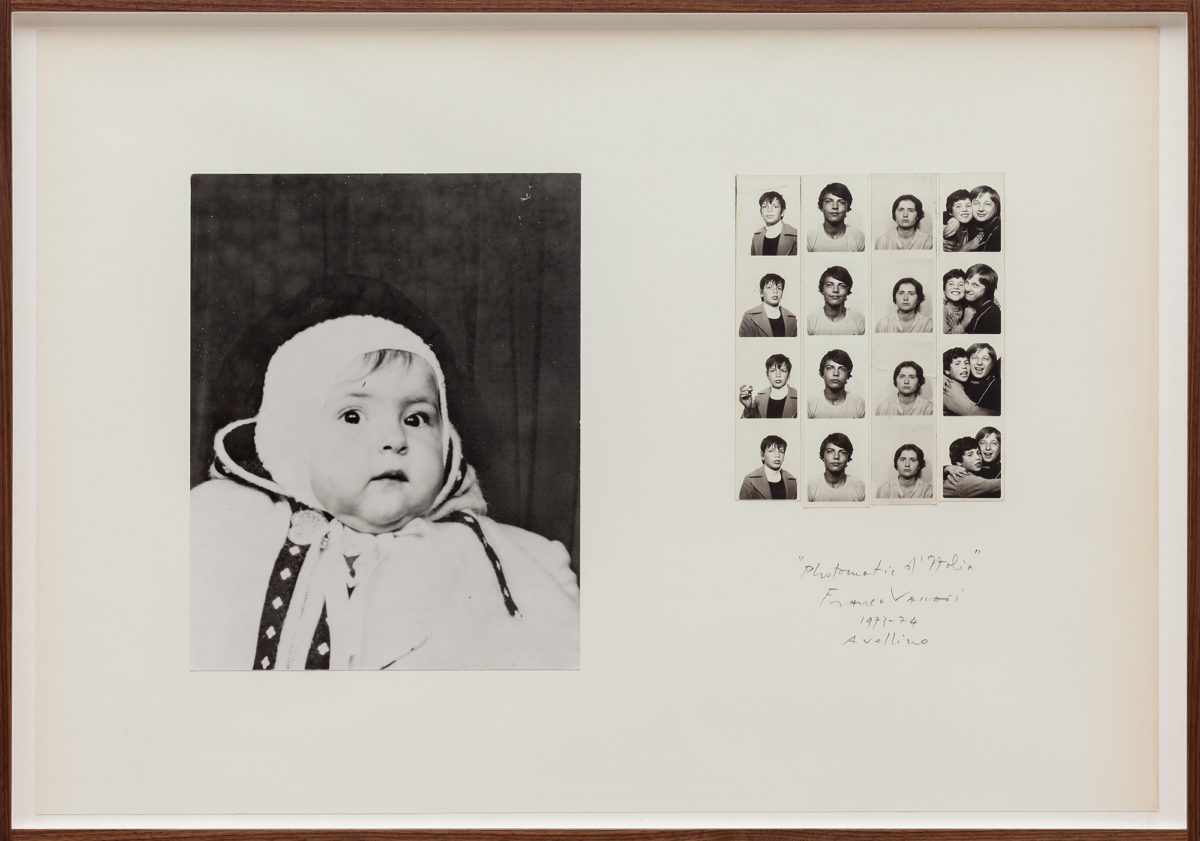

- Left to right: Photomatic d'Italia (Caserta), 1973-74; Photomatic d’Italia (Avellino), 1973–74; Photomatic d'Italia (Napoli), 1973-74. All courtesy the artist and P420, Bologna

“Vaccari’s work made me acutely aware of the disconnect between how we present ourselves visually and our shabby, imperfect realities”

I still have the project that I never submitted after that sleepless night. I failed the module. Flipping through it now, I couldn’t put a name to all of the faces I see, grinning out at me from the album’s pages. Some would be friends for life. Others would fade into indistinct, shadowy blurs in my mind. On the final page is Alessandro.

I was a fool, and for that I take full responsibility. Franco Vaccari’s Photomatic d’Italia made me vow never to let a romantic attachment to a man negatively affect my work or my career again. It marked the end of a destructive love affair. But most of all, Vaccari’s work made me acutely aware of the disconnect between how we present ourselves visually and our shabby, imperfect realities. Alessandro was all image. When I look at that photo strip of him now, I understand the infatuation. I think ah, yes, I see now. And I also think: never again.

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color

READ NOW