In today’s age of social media #activism, it’s hardly radical to point out that at a very basic, aesthetic level, there’s no difference between the genders when it comes to a nipple. In fact, however you identify, all nipples are different. All nipples, too, are inherently politicized. And unless you’re the sort of person who routinely, indignantly asks Twitter when International Men’s Day is every time International Women’s Day comes around (it’s 19 November, as Richard Herring will point out), you’ll see that censoring women’s nips and not men’s is unjust.

You’ll also know that women’s breasts hold a hell of a lot more misogynized sexual currency than men’s. For all this goes-without-saying stuff—and the various Free the Nipple campaigns that have rumbled on since 2012—the big social media platforms still happily let a fella go topless, but censor women doing the same. “Censorship on these platforms says that nipples are offensive, but only on a femme body. It’s a way of shaming a person,” says photographer Michael Bailey-Gates.

“Censorship on these platforms says that nipples are offensive, but only on a femme body. It’s a way of shaming a person”

Social media regulations when it comes to nipples are varied, and slightly confusing: as a rule, as The Verge reports, “pictures of post-mastectomy scarring and breastfeeding are generally okay, as is nudity in art,” though any images outside of that are forbidden by Instagram; while Twitter is more open as long as content is marked as sensitive. In 2018, Facebook’s Community Guidelines stated that its nudity policies have become “more nuanced over time,” claiming to have made moves to recognise that uncovered female bodies can be used as protest and awareness raising rather than simply for sexual ogling.

Facebook states, “While we restrict some images of female breasts that include the nipple, we allow other images, including those depicting acts of protest [nothing in the guidelines state what this means exactly], women actively engaged in breastfeeding, and photos of post-mastectomy scarring.” Until 2015, breastfeeding images were forbidden on Instagram.

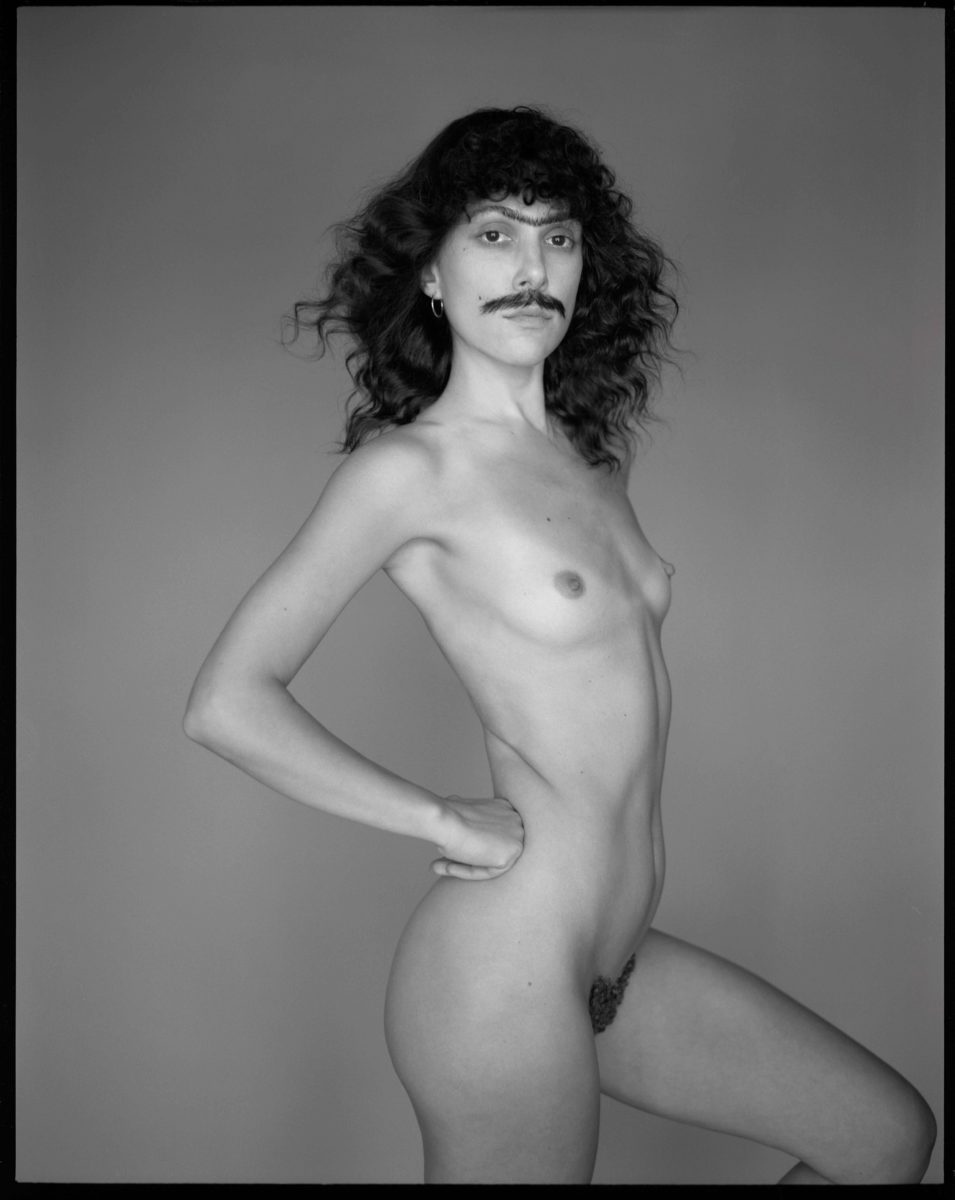

Bailey-Gates is one of the artists whose work is displayed in the online photography project Terms & Conditions. Hosted by photography platform Format, the exhibition features work by forty-nine photographers of various generations, styles and, of course, genders. Thankfully, it’s not just men; and it’s not just glossy fashion editorials, pert titties and titililating portraiture. Of course, there’s a bit of that here—and perhaps not quite as much variation as we’d hope in terms of body shape and binary-breaking—but clearly an effort has been made to steer away from dull, male-gaze objectification.

There’s some beautiful work here; and while of course the project is largely a smart way to show off what Format can do (alongside the stated aim to support “uniform representation of the human body on social media”), there’s clearly been an effort made towards representation.

“The minute I have to censor my work for social media, the magic is lost”

Among the artists featured are Mayan Toledano, Harley Weir, David Uzochukwu, Cameron Lee Phan, Kelia Ideishi and Mandy Lyn. For many of the artists, the idea of freeing the nipple isn’t just about gender inequality, but artistic integrity. “The minute I have to censor my work for social media, the magic is lost,” photographer Kalya Mann writes on the platform. “In this moment, the intent behind my art is broken, and the meaning behind it is diminished. While society has painted breasts to be provocative and inviting to sexual thoughts, in reality, nudity emulates confidence, vulnerability, and nature in its purest form.”

San Francisco-based photographer Madeline Louise adds, “When I photograph the female figure, it is to capture my emotions in a way I cannot verbalize. By having to blur or cover up a very small part of the body (a part that everyone has), the focus shifts away from the subject.”