Édgar Calel (Proyectos Ultravioleta)

Finding fresh fruit and vegetables perched on rocks was a surprise at this year’s Frieze. At the Proyectos Ultravioleta booth, it was difficult to figure out what Édgar Calel, an artist from Comalapa, an indigenous Maya Kaqchikel community in Guatemala, was selling at all.

The day before the fair opened, Calel ritually cut open the watermelon, bananas and pineapples before arranging them carefully on the surface of the stone. This served as an offering for his ancestors and other members of the Mayan indigenous community, acknowledging those who came before. The rocks came from the English countryside, while the fruit was purchased in Brixton, South London. The artist stated, “The stones are not just stones. These fruits are not just fruits.” (Louise Benson)

Andrew Pierre Hart (Tiwani Contemporary)

After sharing the Hayward Gallery walls with the likes of Lisa Brice and Oscar Murillo as part of Mixing It Up, Andrew Pierre Hart presents a rich mixed media installation with Tiwani Contemporary, exploring the relationship between the visual and sonic. A 45-minute soundscape, featuring saxophone by Shabaka Hutchings and Blue Cloud, accompanies Hart’s unseen paintings: shadowy, cryptic studies of sociality and stature rendered in a dusky indigo.

With sound works sparsely represented at this year’s fair, Hart’s multisensory booth commands a slower, more conscious appreciation, while his chequered swirls keep the mind busy and ambiguity open. (Ravi Ghosh)

Sin Wai Kin (Blindspot Gallery)

Their dreamy boyband installation It’s Always You sees Sin Wai Kin literally embody the heartthrob. In this deft exploration of the queer narratives, romantic paradigms and gendered expectations embedded within the pop group construct, they consider the contradictions and freedoms found within the seemingly binary confines of masculinity.

Life-sized cut-outs of the four band members each represent a very particular constructed personality that blends popstar aesthetics with mythological symbolism. Meanwhile the two-channel film installation features a surreal take on the karaoke video, complete with group choreography and vocals that subvert saccharine lyrics to consider the multiplicities of gender. All interspersed with the sound of a mesmeric, throbbing heartbeat. (Holly Black)

Johnson Eziefula (The Breeder)

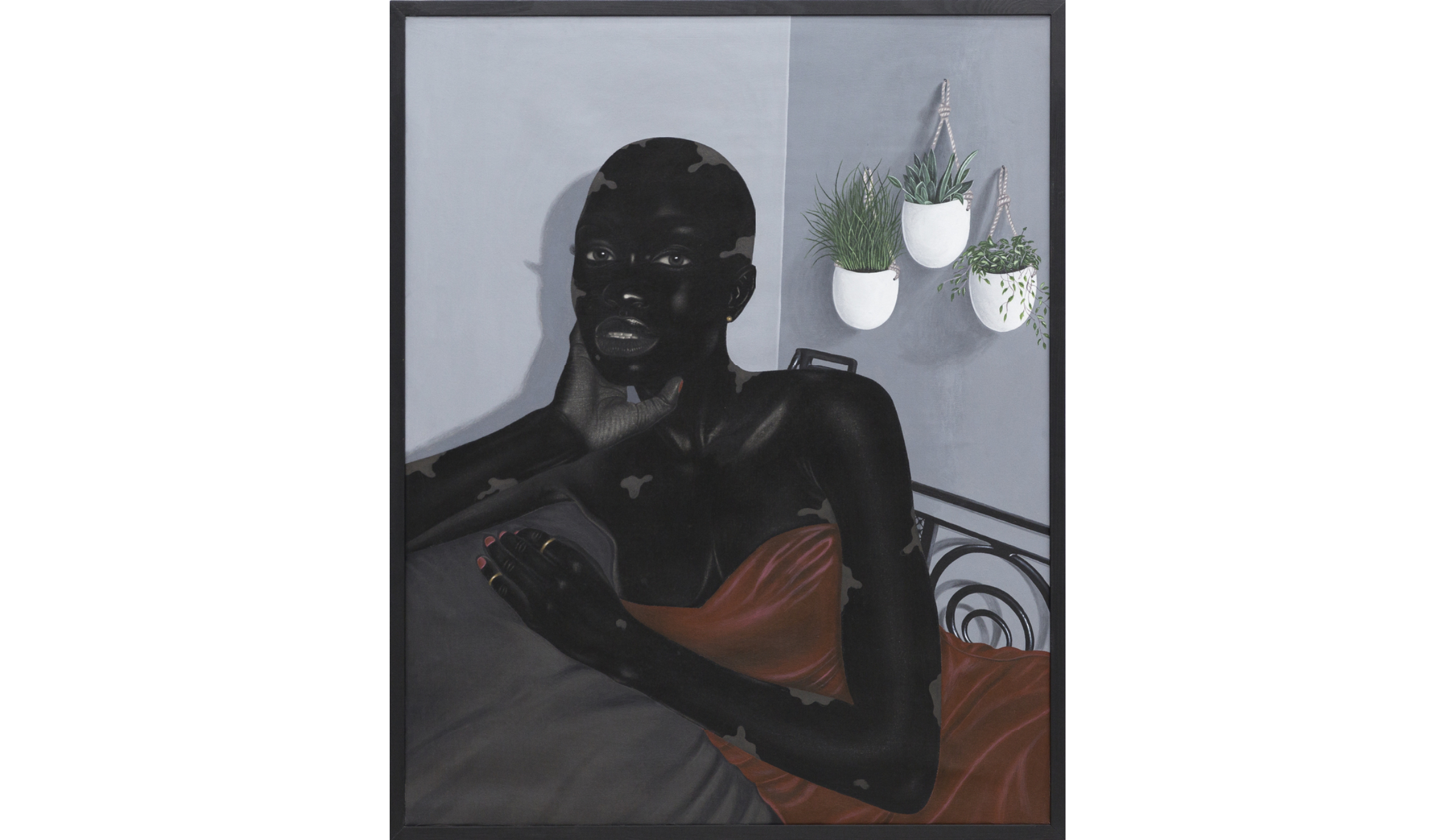

The Breeder has one of the fair’s strongest booths, bringing together a fantastic selection of painters, contemporary sculpture, wall drawings and even a cheeky phallic Man Ray carving. One of the stand-out painters is Johnson Eziefula, whose portrait of a seated woman draped in orange silk, her head gently resting in her hand and gazing directly at the viewer, is instantly arresting.

Three hanging white pot plants in the background of the painting situate this figure very definitely in the contemporary world, but there is a classic stillness to her pose that resonates strongly with historical paintings. The self-proclaimed “biographer of the unnoticed” is adept at capturing his subject’s gaze in each portrait, meeting the viewer face on and locking them into a powerful exchange. (Emily Steer)

Cathrin Hoffmann (Galerie Tanja Wagner)

Hamburg-based Cathrin Hoffmann translates virtually modelled figures into challenging human forms in paint, posing questions around digital futures and imperfect corporealities. Her canvases show angular surrealist subjects whose bodies bear shades of a single, often metallic colour, while her sculptures, comprised of fibre concrete, silicon, steel and faux fur, show deconstructed and dehumanised forms which veer towards the mechanic.

Hoffmann’s Galerie Tanja Wagner booth is encased in a blue wall painting, allowing her fleshy pink sculptures to hover in space, or in the case of Supposed To Fight—That Was The Deal, lie prone with an arm extended skywards. Nearby, similarly shaped limbs protrude from the floor, a constant conversation between the human and the object. (Ravi Ghosh)

Rene Matić (Arcadia Missa)

Starting in 2018 and concluding this year, Rene Matić has explored questions of English identity in her photo series Flags for Countries That Don’t Exist But Bodies That Do. In these vivid, high-contrast images of council estates, seaside towns and political graffiti, she weaves a personal story that raises questions around who is made visible and who disappears from sight when it comes to migration, diaspora and the fraught notion of belonging.

Matić interrogates their own relationship to Britishness, one divided by a simultaneous love-hate antagonism born out of their experiences as a queer Black womxn living in London. It was announced on the first public day of the fair that the Tate would acquire 15 photographs from the series for their permanent collection. (Louise Benson)

Koak (Union Pacific)

With deliciously curvaceous lines and highly pigmented hues, Koak’s five paintings are both alluring and unnerving. Her nude figures, which usually read as ‘feminine’, inhabit domestic spaces that are somehow tinged with horror, whether it be the presence of fiendishly hungry cats, or a doorway into a dark and menacing storm.

Koak has long disputed any overtly erotic reading of her work. As she previously told Elephant: “I find it perplexing that people will look at a drawing of a nude woman and the main thing they see is a sex object”. In reality, these uncanny scenes invite us to luxuriate in their aesthetic before confronting our own assumptions of how images of the female body are consumed. (Holly Black)

Ella Walker (Casey Kaplan)

A former student at Glasgow School of Art and The Royal Drawing School in London, the influence of the latter can really be seen in Ella Walker’s paintings, which carry many of the delicate markings of drawing. Colour is applied to her canvases in washed layers, creating a feeling of transparency in backgrounds, the fabric of clothing and sometimes even human bodies.

Her works are inspired by symbolism and medieval narratives but there is also a contemporary freshness to them, which brings past and present into a single, tangled space. The artist sees parallels between the Middle Ages and the 21st century, both periods experiencing the decline of high culture in their own way. Romantic, beautiful and unsettling in equal measure. (Emily Steer)