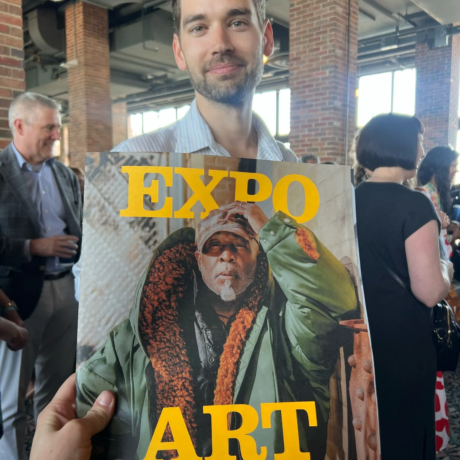

Hossein Qollar-Aqasi Convivial meeting of Kai Khosrow, 1920

Over recent decades, coffee shops have dominated daytime culture as the go-to hangout spot, thanks in no small part to the TV show Friends. Even if today the social aspect of a cafe feels slightly tainted by the pandemic: imagine risking drinking a beverage in a public place simply in order to spend time with a friend?

Coffeehouses are a much older idea than most might think, however. In 16th-century Iran

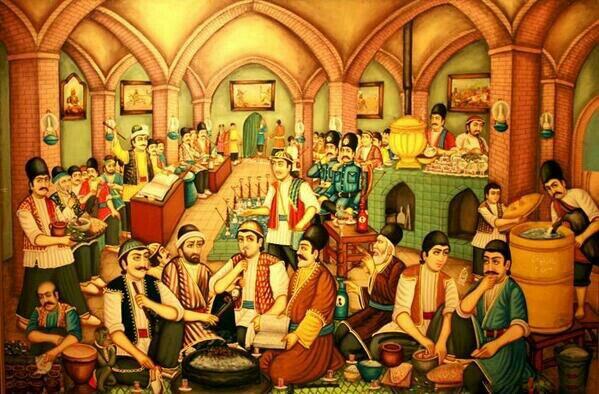

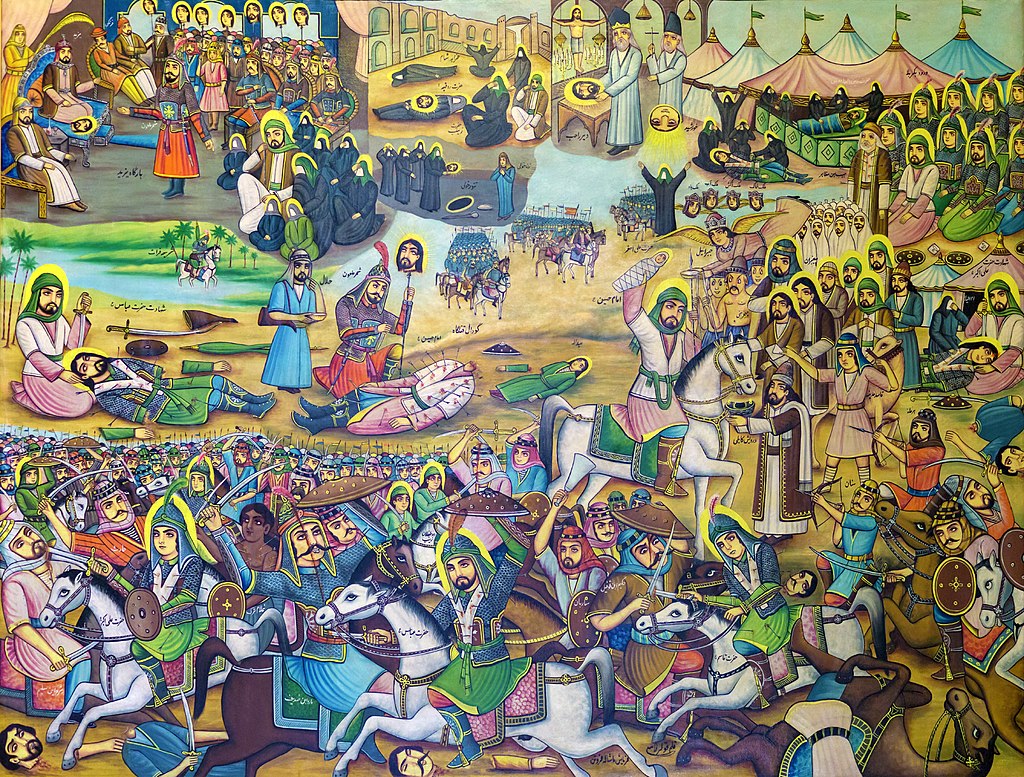

, they were a staple cultural hub: largely patronised by the working and middle classes, they were spaces where performers would recite their work (ranging from philosophy to poetry) in front of audiences, receiving critiques as well as praise. One of the most impactful relics of this time is a style of art dubbed ‘coffeehouse painting’: it accompanied the performances and drew heavily on the stories of the Shahnameh, Iran’s book of Kings. Both decadent in colour and detailed in narrative, coffeehouse art acted as a window into the Iranian way of life.

“In order to talk about coffeehouse painting, we have to talk about the most ancient performance art form in Iran, which was storytelling,” explains Simindokht Dehghani, a gallerist based in Tehran. “Because we had the national stories of our legends and heroes, travellers would visit villages and towns and recount what they had seen or heard.” Iranian coffeehouses were traditionally circular: travellers would stand in the middle, and recount their narratives, while audiences would sit around them. The main stories were taken from the Shahnameh, which was written in the 10th century by the poet Ferdowsi. Similar to Homer’s Iliad, the story is composed of 50,000 verses in rhyming couplets and recounts the stories of kings, their heroes and wives.

Dehghani explains that language plays a significant role within the preservation of Iranian culture. “When the Arabs attacked and brought Islam to Iran, they were unable to get rid of the Persian language,” she says. “So all over the Islamic world today, when you look at most countries in North Africa and the Middle East, they speak Arabic, although they had their own languages. But in the Persian speaking world, which was Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Arabic does not overcome the Persian language.”

This is due to the preservation of the oral tradition of storytelling: stories wouldn’t get written down so much as they would be told to people. Dehghani goes on to say that the Arabs burned whatever written work there was in Iran to get rid of the local culture. However, figurative painting persisted, despite being forbidden in all other areas of the Islamic world. “So what happens is we have this oral tradition, then Islam brings its alphabet, which we take and add other things to,” she explains. “We start writing down our stories, along with the paintings and drawings that we had.”

“Decadent in colour and detailed in narrative, coffeehouse art acted as a window into the Iranian way of life”

These drawings soon made their way onto cloth, or curtains, which could be folded. Travellers would take them along whenever they journeyed to a new city, and would unfold the pardehs (curtains), hang them up, and narrate the accompanying story at coffeehouses for paying audiences. The first coffeehouses opened up in the 16th century in Iran, and were places where artists, poets and philosophers would gather to drink coffee, smoke hookahs and have lunch. The buildings had high ceilings, and benches covered in carpet were arranged in a concentric fashion, so audiences could recline and face performers at the centre. “It was a thriving place for men to gather,” says Dehghani .

“They would open up at around six or seven in the morning until the same time at night. It was when the sun went down in the evenings that the coffeehouses would really come to life,” Candles would light up the interiors, which were decorated with mirrorwork, so the atmosphere shimmered. The coffeehouses were so popular that even the king would visit them to conduct his business, meeting ambassadors from foreign countries. Coffeehouse owners became wise to the fact that storytellers could attract crowds, and soon began paying them a small fee, while also offering them food and a place to sleep. As more audiences were attracted, the orator would paint more pardehs to act as backdrops to their stories.

View this post on Instagram

During the Safavid empire in the 16th century, the king moved the Iranian capital to the city of Esfahan (or Isfahan), in order to build a new city. To facilitate trade with Europe, he drafted in Armenian craftsmen and traders to work on the project. The Armenians were Christians, and brought with them a tradition of painting Bible stories on church walls. Armenian culture flourished in Esfahan, so at the height of the Safavid period it was a thriving, wealthy community with as many as 40 churches in the city. Dehghani points to Chehel Sotoun Palace, which functioned as the summer palace of the king, where wall frescoes exist that are very similar to those painted in the churches.

“It’s quite possible that the king would see the church paintings and ask that similar scenes of his court and battles be painted in his palace,” she suggests. “So from these very basic curtain paintings, the tradition is translated onto walls, and then during the Qajar dynasty, it reaches its highest form of expression as the coffeehouse art begins to be painted onto canvas.” Often these three-metre-long canvases would be hung on the walls of coffeehouses. Dehghani guesses that the move to canvas was inspired by the king’s travels to Europe, where he would have encountered Renaissance paintings.

“It was when the sun went down in the evenings that the coffeehouses would really come to life”

Persian painting is extremely narrative: the composition begins at the top and ends at the bottom. The perspective is flat, differing to European styles, so the painter can depict multiple things happening at once. Dehghani explains that “it’s not because they didn’t know how to paint European perspective or incorporate it into their compositions, but because they wanted to show things happening in order: if you look at Persian miniatures you’ll see this. So there’s a mountain on top, which seems to be in the background, but the person in the mountain is the same person in the middle ground, and the same in the foreground, and they’re all the same size.” The drawings would also have a direct connection to writing within the work.

While coffeehouse painting clearly forms part of a much older tradition, there is unfortunately little evidence to show that this style originated before the 16th century. “Every dynasty, in order to prove its own strengths, would destroy everything from the previous dynasty, and create new things in their own style, to glorify their reign,” explains Dehghani. The one remaining clue is the Esfahan wall frescoes where one can see scenes of the battle and palace court depicted.

Discussing coffeehouse painting’s influence on contemporary Iranian art, Dehghani recalls the evolution of the Saqqakhaneh movement. “There are places in Iran where anyone can drink water for free,” she says. “These always have the face of the martyr Imam Hussein painted on them, who was denied water and killed in a battle of Karbala, Iraq, in 680AD. So in the old bazaar, you will see public water fountains (saqqakhaneh) which are very old with beautiful tile work.”

“Travellers would stand in the middle of the coffeehouses, and recount their narratives, while audiences would sit around them”

In the 1960s, five artists used the term saqqakhaneh to describe a new art movement, which incorporates traditional and national signs and symbols into their art. “Many of these were symbols from the Book of Kings,” says Dehghani. “This movement, to this day, is one of the most important, and is still influencing many of the young artists of the contemporary art scene.” Alongside this, Dehghani points to the work of the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, whose murals have many similarities to coffeehouse paintings.

In the 20th century, the tradition was continued by prominent artists such as Hossein Qollar-Aghasi and his student Mohammed Modabber. Their work was championed by Marcos Grigorian, an Iranian-Armenian artist who was intent on preserving the art of the coffeehouse tradition. Today, the history of Iranian art is explored in the V&A’s Epic Iran exhibit, whose opening was delayed by the UK’s third coronavirus lockdown. While the show doesn’t cover coffeehouse painting specifically, it displays the work of many artists who take influence from this tradition, including Hossein Zenderoudi.

The impact of the coffeehouse tradition should not be forgotten. In Dehghani’s view, “it is these stories of the national heroes that kept our history and language alive.”