In 2009, a year before Wikileaks dumped the diplomatic cables and four prior to Edward Snowden’s last moments on US soil, the journalist and author Francis Wheen published a memoir-cum-history of the 1970s. The book presented a picture of an entire society intoxicated by suspicion, of a mass delirium stretching all the way from the squalid hippie hash dens of Westbourne Grove to Downing Street and the Oval Office. Its title? Strange Days Indeed: The Golden Age of Paranoia. Looking back with almost a decade’s hindsight, it seems Wheen called his “golden age” too soon: in the age of the Trump/Russia allegations, the Cambridge Analytica scandal and “Pizzagate”, current events have made conspiracy theorists of us all. Indeed, blanket internet surveillance and data farming have created a new reality in which Orwellian ideas of a society under total observation actually seem scarily apposite.

These developments have not, of course, been lost on the art world. In timely fashion, the Met Breuer in New York has mounted Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, an exhibition exploring the ways in which artists have reacted to societal paranoia and shadowy institutional intrigues. The show brings together an impressive selection of works that probe into secretive organisations and schemes, respond to conspiracy theories or even, in a few cases, forward their own. Beginning in the 1960s with artists like Peter Saul, Hans Haacke and Alfredo Jaar, it investigates the theme right up to the middle of the last decade.

Pointedly, we don’t get much of a look-in on any art that addresses the present confusion. Politically sensible though it may be, the curators’ decision to keep things historical feels just a little disappointing. While much of the higher profile work created in response to current uncertainties has taken a fatuous, caricature-level approach to its subjects (notably Trump and Brexit), the past decade has produced some intelligent, eye opening and genuinely terrifying art on the theme. Three contemporary artists are additionally included below, offering up some of the more impressive artistic reactions to the more or less rational obsessions of modern society, to bring us more or less up to date. Enjoy—and remember: just because you’re not paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not watching you.

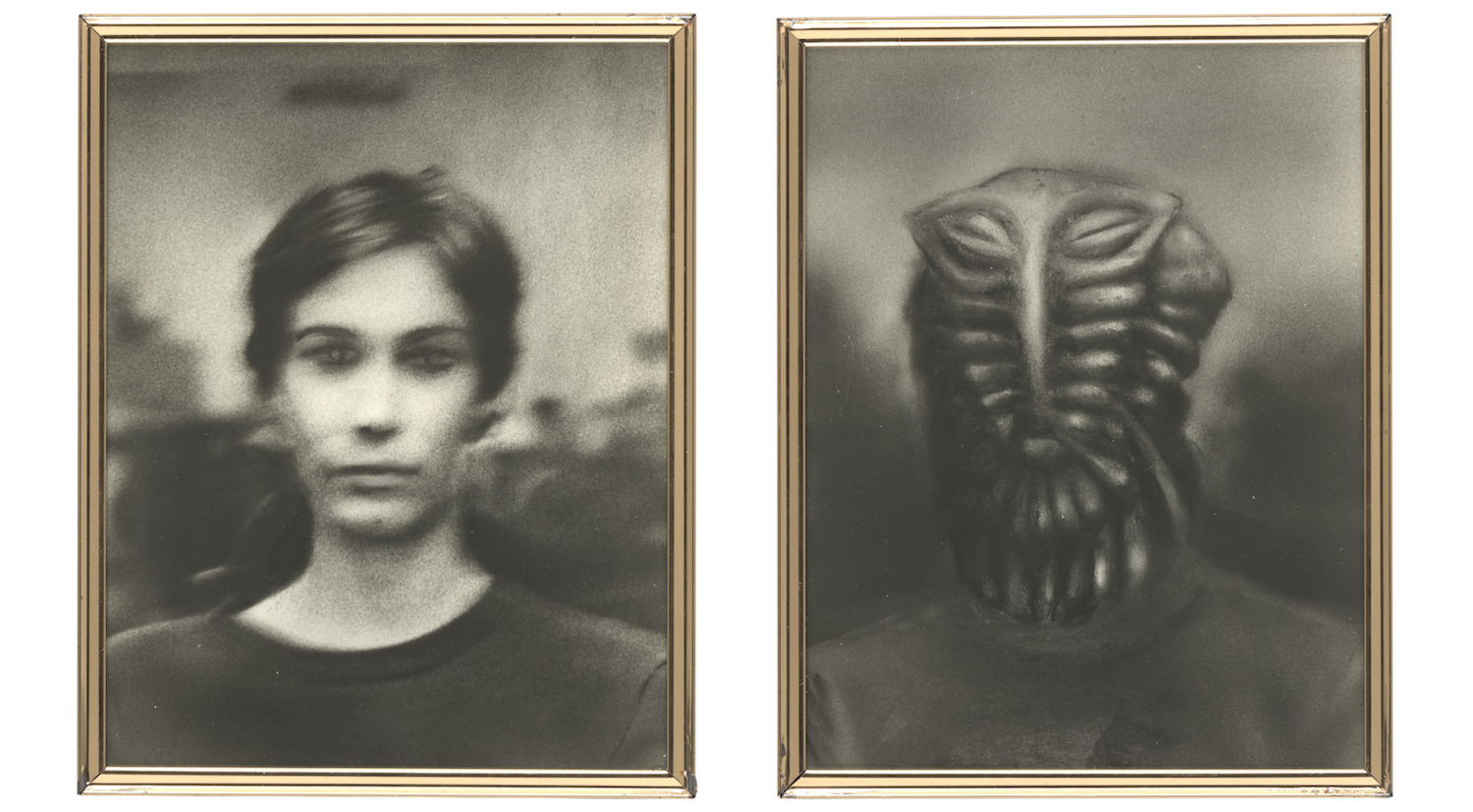

Jim Shaw, Martian Portraits, 1978

In times of heightened uncertainty, the thinking goes, we tend to project our anxieties onto inexplicable phenomena. In the 1970s, if you accept the argument, this manifested itself in a surfeit of UFO sightings—notably in the USA, and particularly in California. Jim Shaw, a graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, took a wry, detached view of the public obsession with alien encounters, noting how shoddy much of the so-called “photographic evidence” for these fantastical tales was. This is one of a number of satirical forged documentations he created, all of which deliberately imitate and exaggerate the poor-quality of the image manipulation.

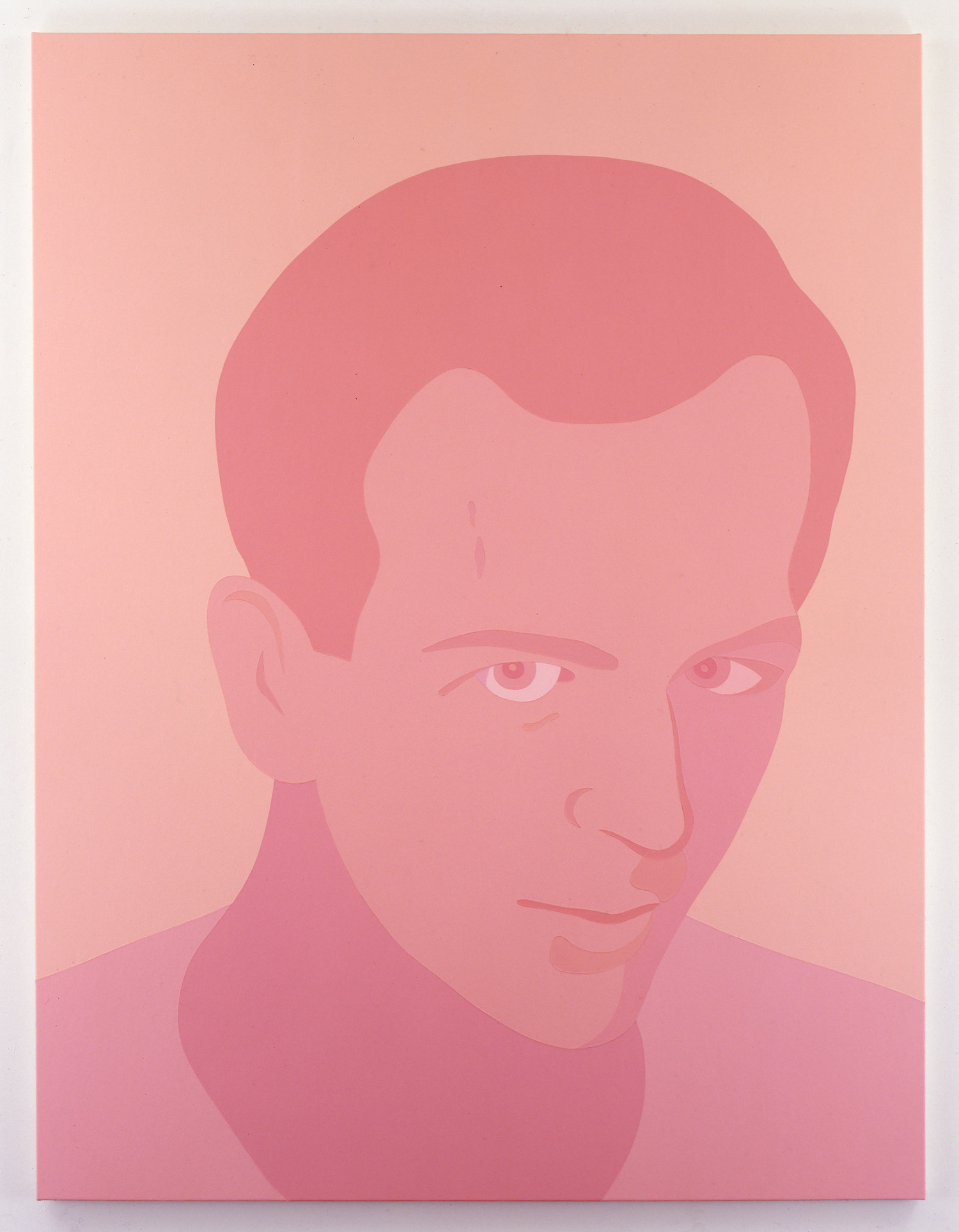

Wayne Gonzalez, Peach Oswald, 1999

The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 provoked countless conspiracy theories. The accepted story—that the President was shot by known Communist Lee Harvey Oswald, who was in turn murdered later that night by club boss Jack Ruby—was immediately thrown into doubt by sceptics. Small wonder: even authority figures refused to accept this narrative, with a local district attorney declaring that the supposed killer “never fired a shot”, and may himself have been the victim of a CIA cover-up. We can theorize all we want, but the only person who could have known the veracity of the official testament was Oswald himself. Wayne Gonzales, an artist who grew up on the same street as Oswald, separates his subject from the context with which he has become synonymous, bringing his gaze almost to eye level. Suddenly, this historical cypher, either the incarnation of evil or a fall guy, depending on your view, is finally given a little humanity.

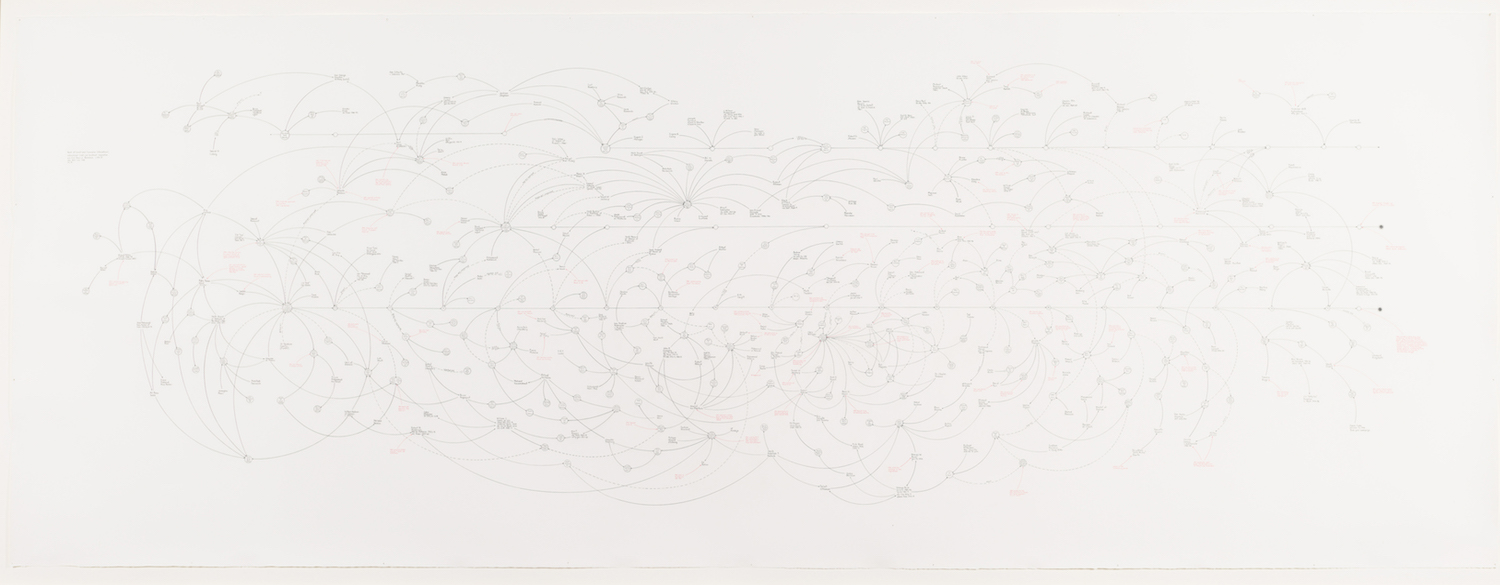

Mark Lombardi, Bill Clinton, the Lippo Group, and Jackson Stephens of Little Rock, Arkansas (5th Version), 1999

The late Mark Lombardi specialised in encyclopaedic flowcharts that connected impossibly diverse individuals and organisations with what we might describe as “persons of interest”: think of them as the dark side of the “six degrees of separation” principle. This example, created not long after the Lewinsky affair, links then-President Bill Clinton with James Liady, the businessman at the head of the Indonesian property company Lippo Group, throwing up a series of suspicious business dealings. Whether or not you consider it a condemnation of the Clinton administration, it gives visual shape to the opaque relations between executive power and secretive business networks.

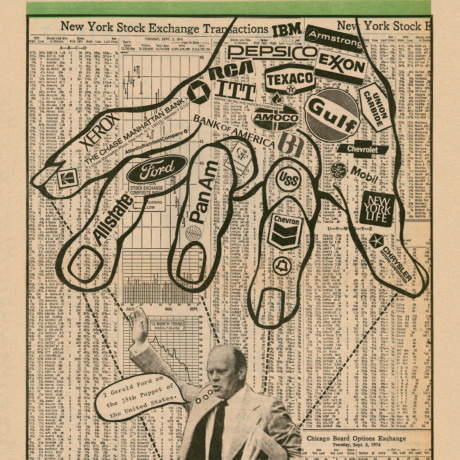

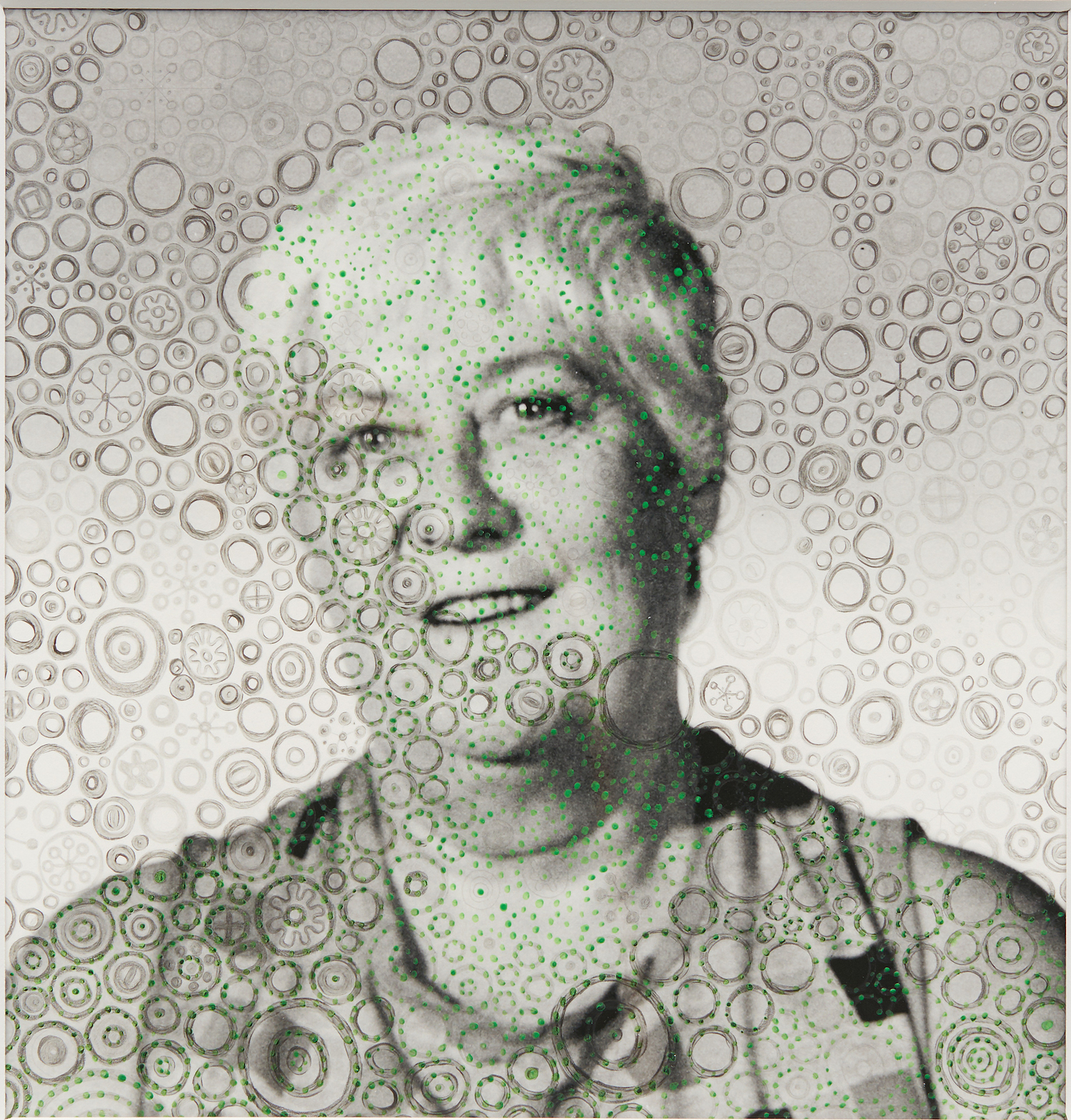

Sarah Anne Johnson, Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, 2008

This image belongs to a harrowing body of work by Canadian artist Sarah Anne Johnson, whose grandmother was part of the infamous, CIA-sponsored MK ULTRA mind control programme. This widespread initiative, launched in 1953 at around eighty different institutions, involved subjecting volunteers to brainwashing experiments involving electroshock treatment and psychoactive drugs including LSD, all for the purpose of military research. Though its subjects were willing, the “treatment” they received left many scarred for life. The research was eventually wrapped up in 1967, and kept secret for another decade before being acknowledged by the American authorities.

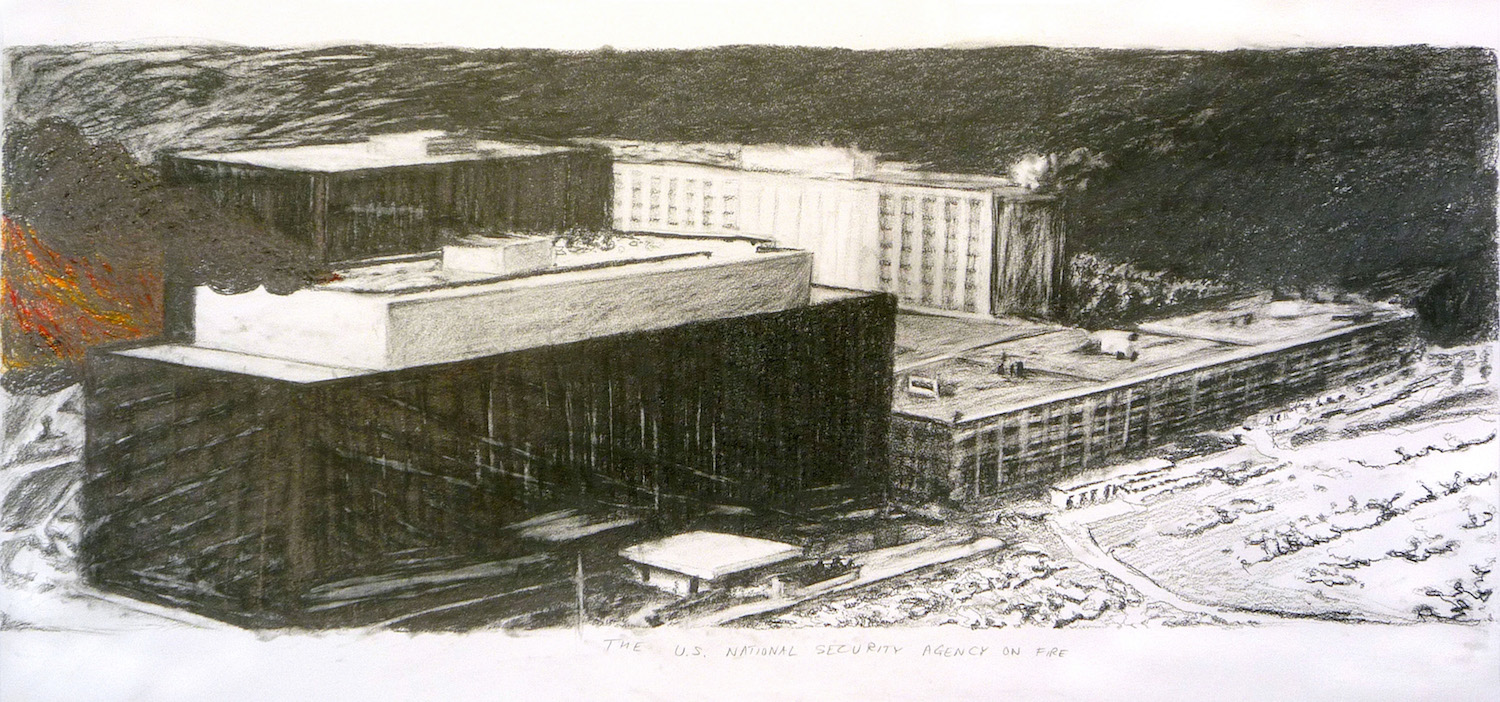

Suzanne Treister, The US National Security Agency on Fire, 2010

Long before the rest of us started paying attention, Suzanne Treister became aware that internet users were inadvertently disclosing a vast amount of personal data that flowed directly into the hands of state intelligence organisations. She created a number of works on the subject, but her research into the topic saw many brand her as—by her own account—a “paranoid conspiracy theorist”. Then came the Snowden revelations, and a total vindication of her efforts. “With the Snowden information, it was already out there if you looked for it,” she told me in 2014. “It was obvious how the data from social networking and commercial websites was providing information to security agencies and what kind of society this may lead us into.”

Bonnie Camplin, The Military Industrial Complex, 2015

“‘Conspiracy Theory’ acts as a derisive dismissal which serves to characterise counter-narratives as falsehoods or fantasy,” the American anarchist Lawrence Jarach once wrote. This might well have prefaced Bonnie Camplin’s 2015 exhibition at the South London Gallery. The installation consisted of a “study room” dedicated to defining the essence of “consensus reality”: that is, the agreed truth of how society works and what, exactly, makes it tick. Featuring an apparently arbitrary array of texts and videos on everything from psychology and quantum physics to military strategy and witchcraft, it presents our received notion of the world we inhabit as a fragile superstition built on random subjectivity.

Trevor Paglen, Fanon, 2017

Trevor Paglen is probably the best-known artist currently investigating the uncertainties of the present moment. In this, one of his most unusual works, he focuses on what might be described as the “visual imagination” of AI programmes. On the face of it, this image appears to be a straightforward portrait of the theorist Franz Fanon; in reality, however, it is a mathematical abstraction, the product of a complex algorithm that has been fed a set of data roughly corresponding to the features of Fanon’s face. With this and other works, Paglen taps deep into uncertainties surrounding the growing importance of artificial intelligence, allowing us to “see” through the eyes of machines. Whether or not our fears about AI have any rational base remains to be seen, but Paglen’s efforts make the world of Blade Runner seem uncomfortably real.