Every corner of Mary Beth Edelson’s large studio in Manhattan’s SoHo district exploded with images of potent, whip-smart, sexually liberated, self-actualising women. They avenged if wronged (Lorena Bobbitt), bore their vulvas with pride (the ancient folkloric goddess Sheela-na-gig), and worked interminably to centre women’s art and experience (Judy Chicago, Yoko Ono, Faith Ringgold, and so many more). Their visceral, convention-shaking power stretched deep into history and (as inferred in Edelson’s art) would push endlessly into the future.

“There is a feminist adage: ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. To which I say: ‘Let’s get some other tools! Fuck his house—who goes there anyway?’,” Edelson once wrote of her generative feminist art. “I’ve always felt that we can claim our own tools by deeply examining history, by researching the eras when women were revered in a different way—or so the myth goes.”

Born in 1933, Edelson began making art as a teenager in her native Chicago. It was between art school and moving around the country (Indiana, Florida, New York, Washington DC) as a young adult in the 1960s, that she started excavating the subject that would inform her work moving forward: the wide, devastatingly underrepresented spectrum of female strength.

As the feminist movement took hold, she abandoned the abstract-expressionist painting that art school typically encouraged and instead embraced conceptual art, blending collage, performance, collective action, and activism. Her medium became images of powerful women and goddesses throughout history—or using her own body to channel them. Her method was, in the words of scholar Laura Cottingham, “to disrupt and transform the patriarchal pictorial codes that define and limit female identity.”

“‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. Fuck his house—who goes there anyway?”

The early 1970s were foundational for Edelson, with both her individual work and passionate commitment to organising serving as wellsprings for the feminist art movement. In 1971, she organised a picket line at the Corcoran Gallery of Art to protest the museum’s all-male biennial. The following year she spearheaded the first National Conference for Women in the Visual Arts, drawing women from across the country and using her bedroom as the conference headquarters. It was a deeply personal and political affair.

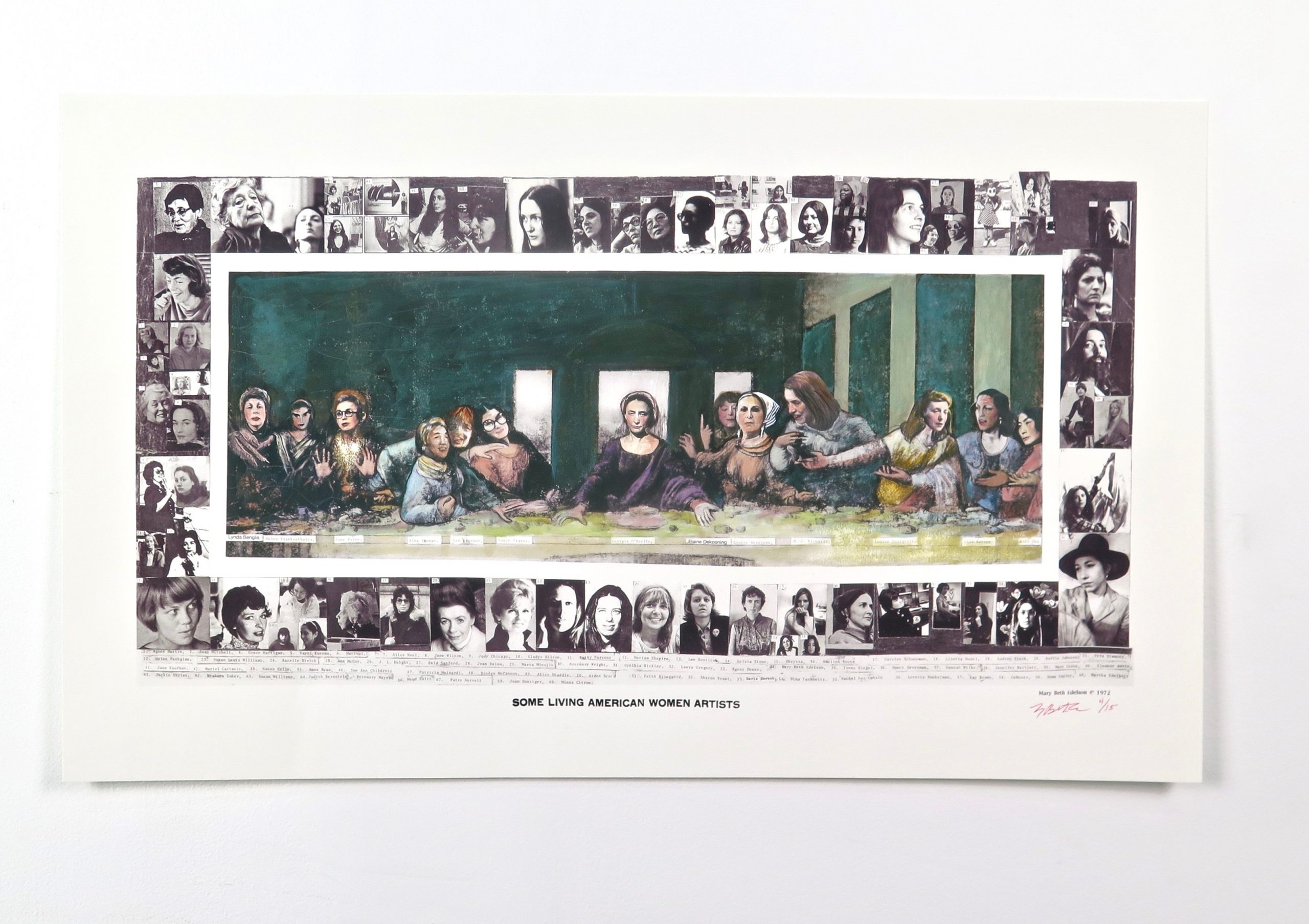

At the same time, Edelson forged her most famous work, Some Living American Women Artists (1972), a collage that deals in a dual take-down of organised religion and the patriarchy. Using photos of path-breaking female artists, both her forebears and her contemporaries, Edelson replaced the male faces of Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper with female artists including Georgia O’Keeffe, Alma Thomas, Yoko Ono, and Lee Krasner. A grid of some 50 additional portraits ring the main image, complete with a key of typed names, a cheeky and tenaciously commemorative record of women changing the male-dominated art game. “I want to honour these women who gave so much of their time in the 1970s to building the feminist movement, and stuck with it, making it happen,” she mused of her early collages.

“I am depicting the holistic, centred, assertive, sexual, spiritual woman who is in the process of becoming”

More provocative collages, ritualistic performances, and collective actions followed. Her 1973 series Woman Rising and Monstre Sacré saw Edelson pose in powerful, honorific stances in wild, windswept landscapes, channelling ancient goddesses and primal cries. She then transformed photos of the actions with serpentine drawings and collaged elements pulled from her ever-growing archive of female deities. “The result is a mutable, fantastic body that references archetypal modes without being tied down to a predetermined system,” says writer Dodie Bellamy of the work, in a resplendently thoughtful 2019 essay

.

Among a rich body of work that Edelson continued to develop in her New York studio into her eighties (she passed away in April 2021 at the age of 88) other significant pieces include her ego-busting, collaborative work Story Gathering Boxes (1972); the 1977 co-founding of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics; her 1994 sculpture that fused two avenging women, the Hindu goddess Kali and the cultural figure Lorena Bobbitt; and even a 1994 series of self-defence workshops.

At its molten core, Edelson’s work is powered by the long history of female representation, and her playful, potent ability to re-shape and reclaim it is both centring and abidingly empowering. As Lucy Lippard put it when speaking of Edelson’s practice: “She re-mythologises at the same time she de-mythologises.” And in Edelson’s own fiery, searing words: “I am depicting the holistic, centred, assertive, sexual, spiritual woman who is in the process of becoming, balancing her mind/body/spirit. I am using my body in these rituals as a stand-in for the Goddess, as a stand-in for the everywoman.”