Drew Zeiba meets with Funto Omojola and Precious Okoyomon to discuss Funto’s debut poetry collection and the similarities between both of their practices.

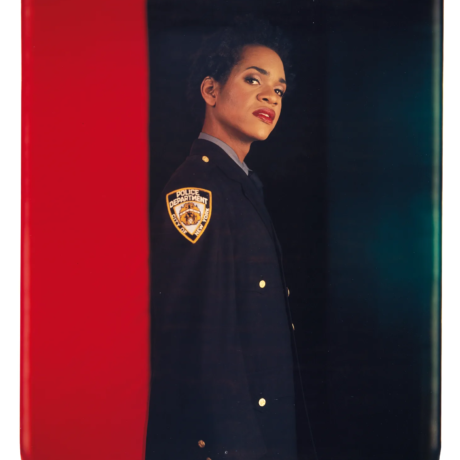

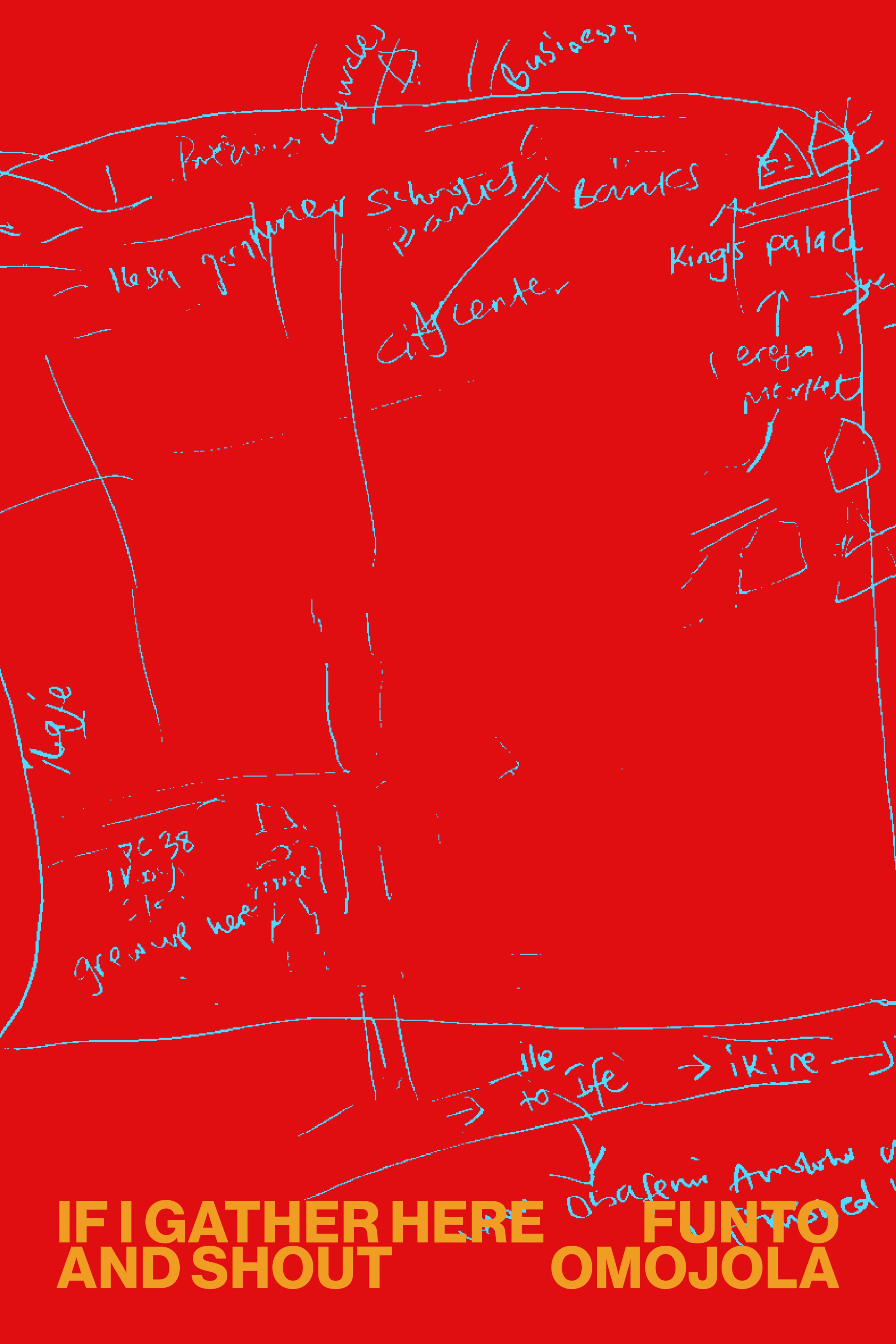

“There are not many disciples left,” writes Funto Omojola in their debut poetry collection, If I Gather Here and Shout, published by Nightboat Books this November. I first misread this line with “disciplines,” and maybe Omojola would agree. Working across photography, sound, installation, poetry, and movement, the writer and artist has performed and exhibited widely, including recently at A.I.R. Gallery in Brooklyn and as part of the Carrie Mae Weems-organized Remember to Dream nine-hour election-day gathering at Gladstone Gallery in Manhattan.

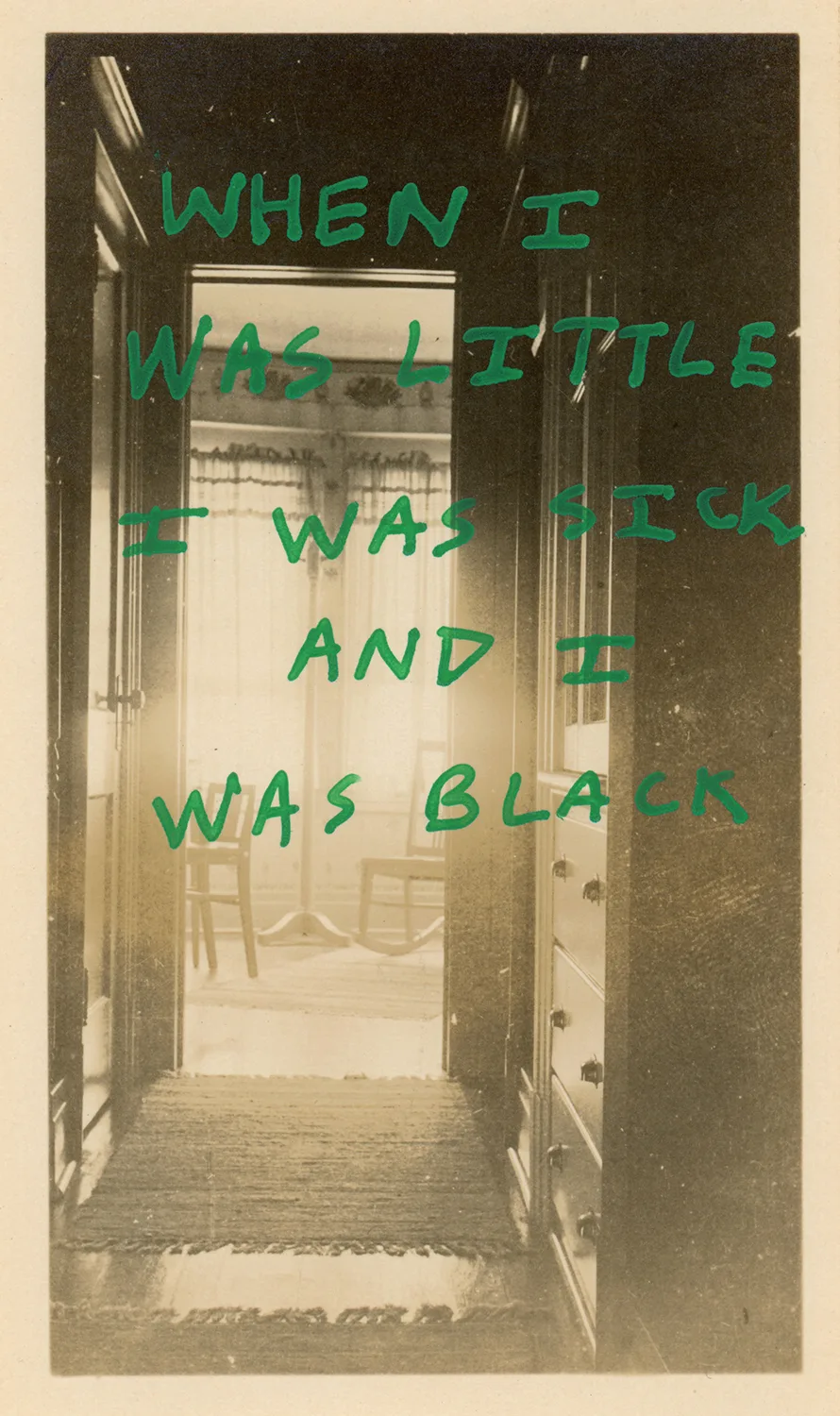

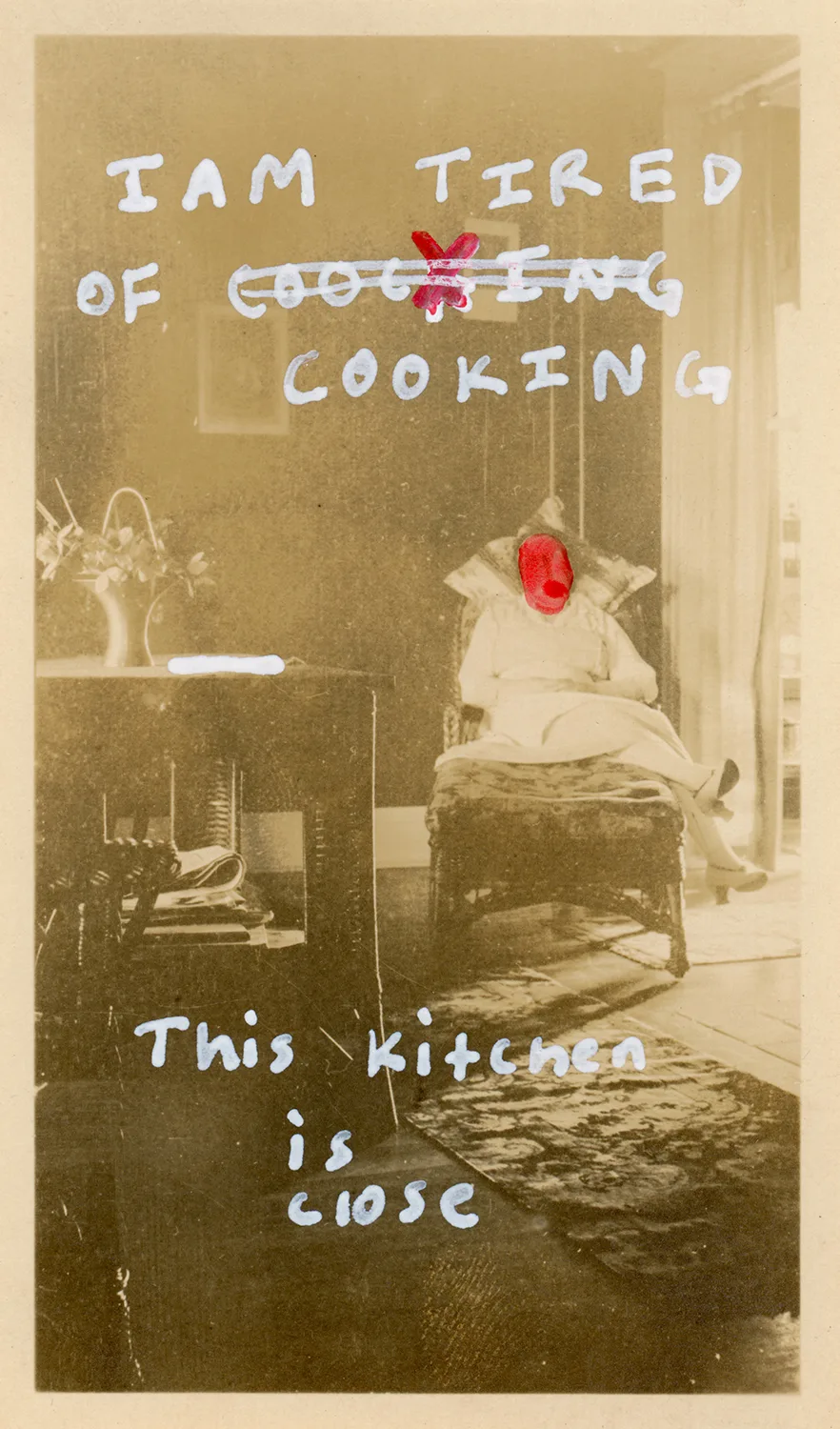

If I Gather Here and Shout blurs forms and voices seemingly across timelines and metaphysical realms. Woven throughout the book are discourses about divination and the dùndún drum from what registers as an outside interlocutor and histories of family members—like Grandpa Ado who broke his arms in a motorcycle accident and so “the people at st. gregory on basiri street / covered him in plaster of paris and he spent january with arms / outstretched like Jesus.” Omojola blends direct and oblique ruminations on inhabiting an ill body: “say girl body into machine, / lungs. How many worms legless hurdling hurdling toward machine, / lungs also? This is all for superstition,” they write. Or: “what a silly thing it is to not really be able to shit!”

In Precious Okoyomon’s recent book of poems, But Did You Die?, co-published by Wonder and the Serpentine Galleries, body (singular and collective), mind, spirit, and space-time likewise elide. The artist and poet—who most recently created this year’s Nigerian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale and has exhibited at institutions including MMK, in Frankfurt, and LUMA Westbau in Zurich—collected their work written roughly from ages 20 to 28 to create a volume that spirals and enfolds, sprawling through accrual as words recur: “drowning,” “dreams,” “dissolve,” mutate in different contexts.

In both books gaps and holes open up. “Inside every hole / I have put my fingers / Is my privatized escape sky torn membrane,” writes Okoyomon. “i am moving. / this my whole hole / this my rotten-ing hole,” writes Omojola. God has many voices. Awe and abjection vibrate together. Pain is not clarity but it is clear. So is ecstasy. As Omojola quotes Fred Moten in their epigraph, “Anybody who thinks they can come even close to understanding how terrible the terror has been without understanding how beautiful the beauty has been against the grain of that terror is wrong.”

Okoyomon’s book is small and felted, with gold-edged, Bible-thin pages. Drawings of frightened flowers sprout throughout. Omojola’s book places “Fig.,” atop many poems yet no image is ever present but an ultrasound—black and white, a bit larger than a thumbnail—credited in the notes to the author. We come to understand the image is not missing or even displaced but latent, imminent, there for those with belief enough to see.

The New York City-based pair met for the first time over Zoom from Boulder, Colorado, and from upstate New York for Elephant.

Funto Omojola: The mouth, the tongue, and swallowing comes up so much in your work. I was curious, to start us off, what your relationship to the mouth or orality is in general, but also specifically in this book?

Precious Okoyomon: It’s always swallowing, digesting, in a constant state of guttural digestion, being digested, eating others. It’s continuous for me, feeding. My love is stuffing other people with food and that process of nurturing. To me, the mouth is the beginning of the heart. It’s this continuous swallowing, witnessing eating, falling into holes and out of them, back in.

FO: The mouth is this gape in my work. I’m Yoruba, so I think of oral traditions where the mouth is crucial for chanting and divination. When I’m thinking about the mouth, it appears as this channel for spells, and when writing, I’m also asking how writing can be incantatory.

PO: I feel that so much. I read a lot of your work as prayers and spells. My last poetry book started as things that I read out loud to myself. How a lot of my poetry is written is I speak to myself, and it’s my voice notes that then gets translated into a poem. It’s these chants, these little prayers of worship,

FO: In a lot of your work, it seems like you’re getting visions.

PO: It’s very visions-from-God, honestly

FO: My mom, ever since I was little, would be like, “I’m psychic. We’re psychic.” Now that I’ve come into writing, I think about being psychic not in the way Westerners think of what it means to be a channel, but I feel like messages are always being passed to me in my sleep. Dreaming is crazy for me. I’m always calling up a friend and being like, “I saw you in this place. This thing is about to happen.”

PO: They’re very important downloads. My mom’s side is Esan. I feel like my mom is definitely tapped in. [Laughs] She’s very much seeing all the time—in the way that she witnesses the world. That taught me how I can make art. Visions or channels through or other feel-knowings that have come before you are passed down continuously, and those memories never die. The dream is the original archive. It is the archives of a transubstantiation that you go back to, you go back into that liquid void where you reach through time and space to articulate knowledge and languages you don’t know. It’s filtered through you. The dream state is the true place for me.

FO: When you’re separated from the land you have to compose from an in-between space cultivated from ancestral understanding. Even when you think about the rhythms of the folk tales, of the stories we’re told as children, there’s a patterning to them that I feel is reflected in a lot of Nigerian writers—all the way from Chinua Achebe to Helen Oyeyemi to other contemporary writers. Even if it’s written, the stories are being passed down orally.

PO: That is a really powerful tool. I’m continuously thinking about spoken archives. When I did the Nigerian Pavilion for Venice, my project was going to Lagos and doing interviews with strangers. I called it a radio tower. It was my archive of asking. I asked everyone a mixture of Bhanu Kapil’s twelve questions and questions I came up with. It was a project of self-fragilization and trying to think about what an original wound looks like. The fragilization between strangers, the passing of tongues—that became a very interesting space of storytelling and memory. There’s always a wound, there’s a break, but I’m asking, “Can I soften with you, and then together we will have a story?” That’s what I’m hungry for, and that flows so easily through your work. Have you read Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive?

FO: Mhm, yes.

PO: I had a similar feeling as I read your work. You have your feet in so many different worlds and you’re flowing in and out through time, which is very beautiful to see.

FO: Thank you. In my case, I was going through health issues. I was in the hospital, dealing with Western medicine and misdiagnosis. Then I would have my mom praying, or people back home saying, “I talked to a priest and I saw this happening.” And so I was thinking about my body as this in-between space where it’s the folk, while being physically in the hospital or detached from the land. A lot of my writing does feel like I’m receiving messages, and I’m a channel and I’m transcribing visions, even when my physical body feels at odds with my material surroundings, or I’m around white people and steeped in a very different understanding of what it means to have an illness or to heal. But it can feel distorted at times, and I want that distortion to come through the language or intonation on the page.

PO: I think about devotion. I grew up in a very Christian household, and I think about the devotional sense of likeworship. What it means for people to pray for you and for that energy to be channeled as that spiritual realm is cosmically unfolding all around you. I think of it as this real cosmic effluvia. It’s a devotional energy that then gets transcribed into language, and I found it reading your poems.

FO: I was thinking about devotion and God in your work. You have so many funny lines: “God doesn’t strike people down like he use 2” or “It’s a bummer nobody gets crucified anymore.” Do you think it’s because God is changing or has changed, or do you think it’s because there are too many people? [Laughs]

PO: I think God’s vibes had to change a little. He couldn’t be Old Testament all the time, which, honestly, I’m like, bring that vengeance…

FO: Because you need more striking.

PO: Striking! God doesn’t hit like he used to.

I was really struggling at that time. That book is very interesting because I wrote it at such a specific time in my life—from when I had just moved to New York, like my early 20s, to 28. It captures my 20s perfectly in this way—falling in and out of holes, into voids, begging God, praying to him. [Laughs.]

FO: I love that there are these yellow pages throughout the book that create a lot of space. But you also write, “Something yellow is drowning me again.” What did that drowning look like at that time?

PO: I often see my life in stages of colors. It’s almost how I transmute the taste of time. During that time, everything was a certain yellow. I was always finding yellow and drowning in it. For me, it was a very suffocating color. It can be very light and lifting, but at the same time I can become very lost in it. I lose myself when I feel myself in terms of yellows. Green is the best for me. Very grounded, really rooted. But yellow, I might as well be floating off into nothing.

FO: It’s funny, because for me, yellows and browns and oranges feel rooted whereas greens and blues feel floating and maybe suffocating. So it’s interesting to hear you say that. Even in the book you’re drawing flowers and suns, but they look like they’re in excruciating pain. There’s fire around their faces and in their eyes. They’re alarmed. What is that for you?

PO: That’s the constant fire. The world is constantly on fire. I think about world endings a lot and how people—usually brown or Black people—are facing that every day, especially living in a big, changing and shifting time and space of people and lands we’ll see come and go and questioning how we navigate that. And I’m like, Oh, the sun is always shining and witnessing, the flowers are growing, and everything is softly burning. It’s softly burning, and how do we live inside of it? It never stops.

Words by Drew Zeiba