In making art about humans’ relationship with future technologies, the challenge is to balance irrational fears with likely realities, all while leaving space for the many unknowables. Newcastle-based Kara Chin strives for this equilibrium in her sculptural installations and animations, which interrogate technology’s unstable future via outlandish fictions and provocative visual responses. Her works, which range from ceramic hangings and upholstered forms to disparate installations, deploy familiar and estranged motifs to create visual juxtapositions, leaving the viewer with a distinct sense of ambivalence, softened by their playful nature.

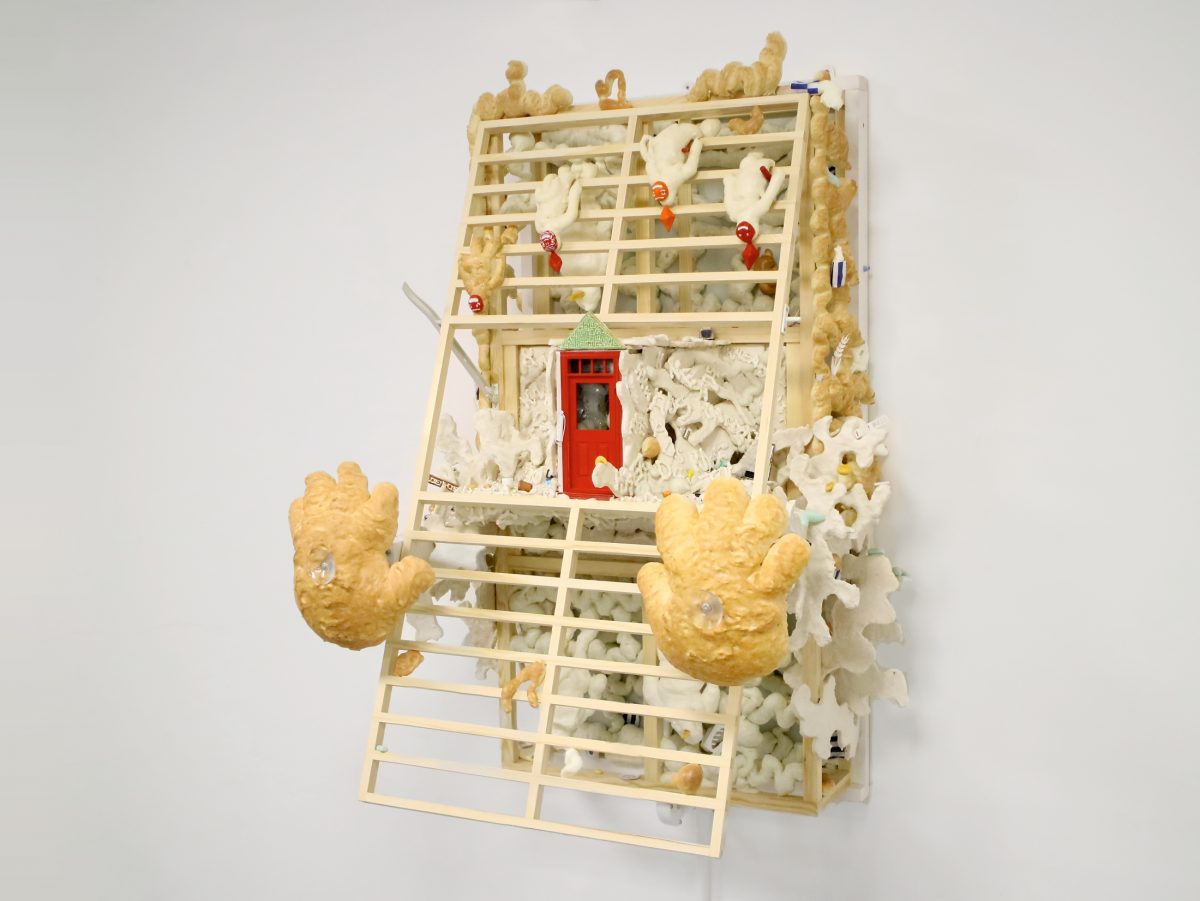

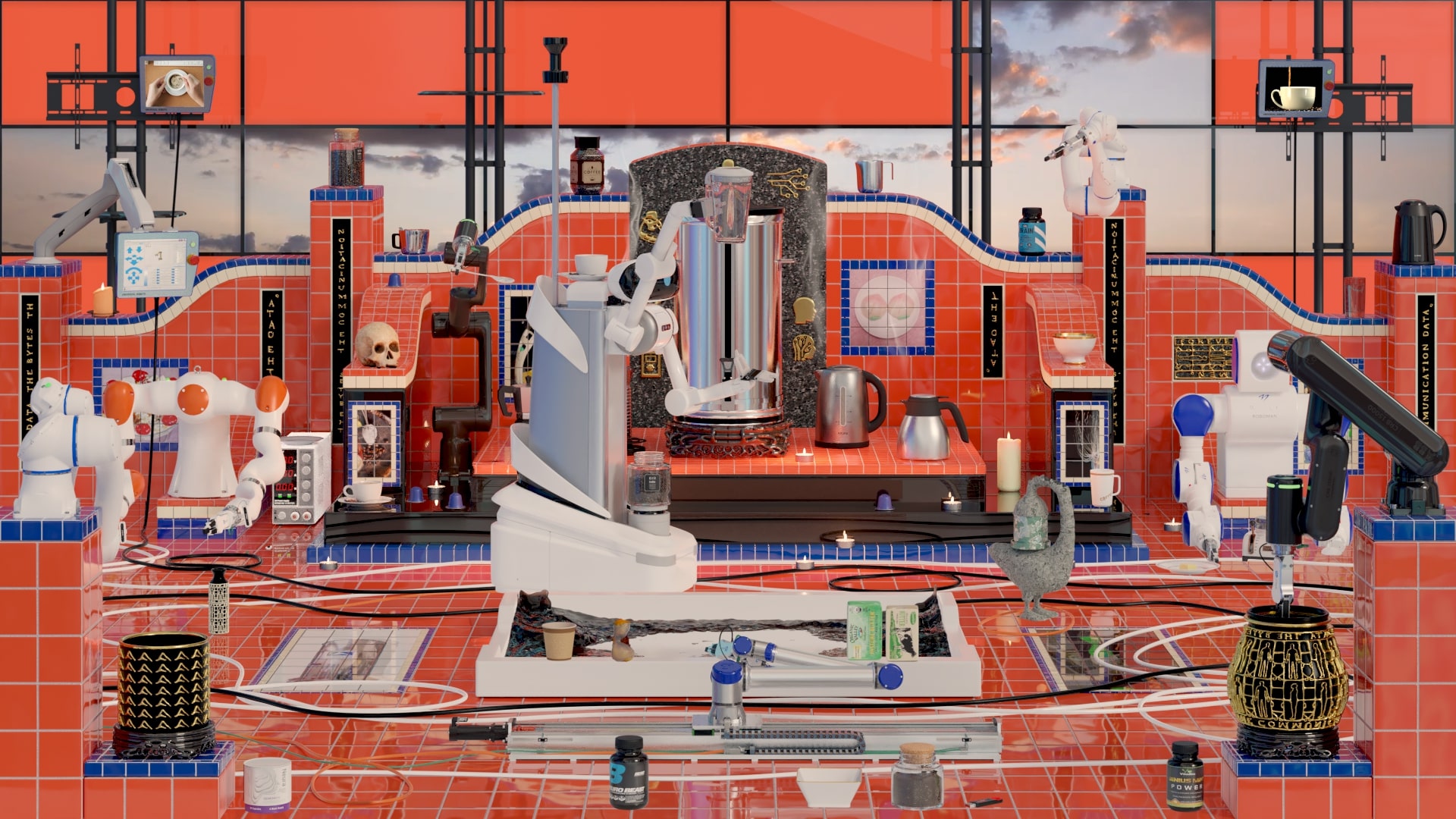

Fountain of Youth, her latest show at Huxley-Parlour in London, is a speculative fiction informed by transhumanism, the belief that “humans can (and should) merge with technology in order to live forever,” Chin explains. The new works emerge from the artist’s interest in the absurd consequences of robots trying and failing to perform simple human tasks, despite their proficiency in other complex areas.

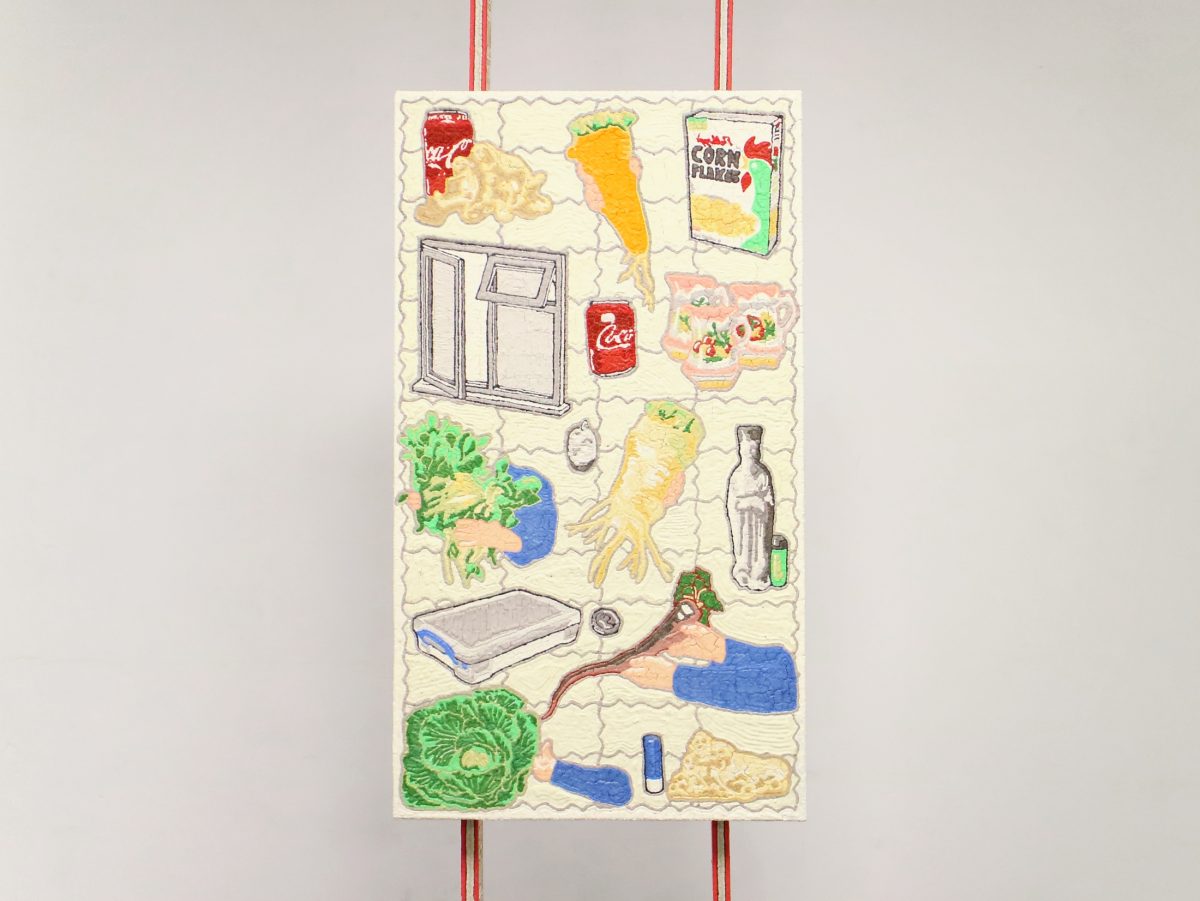

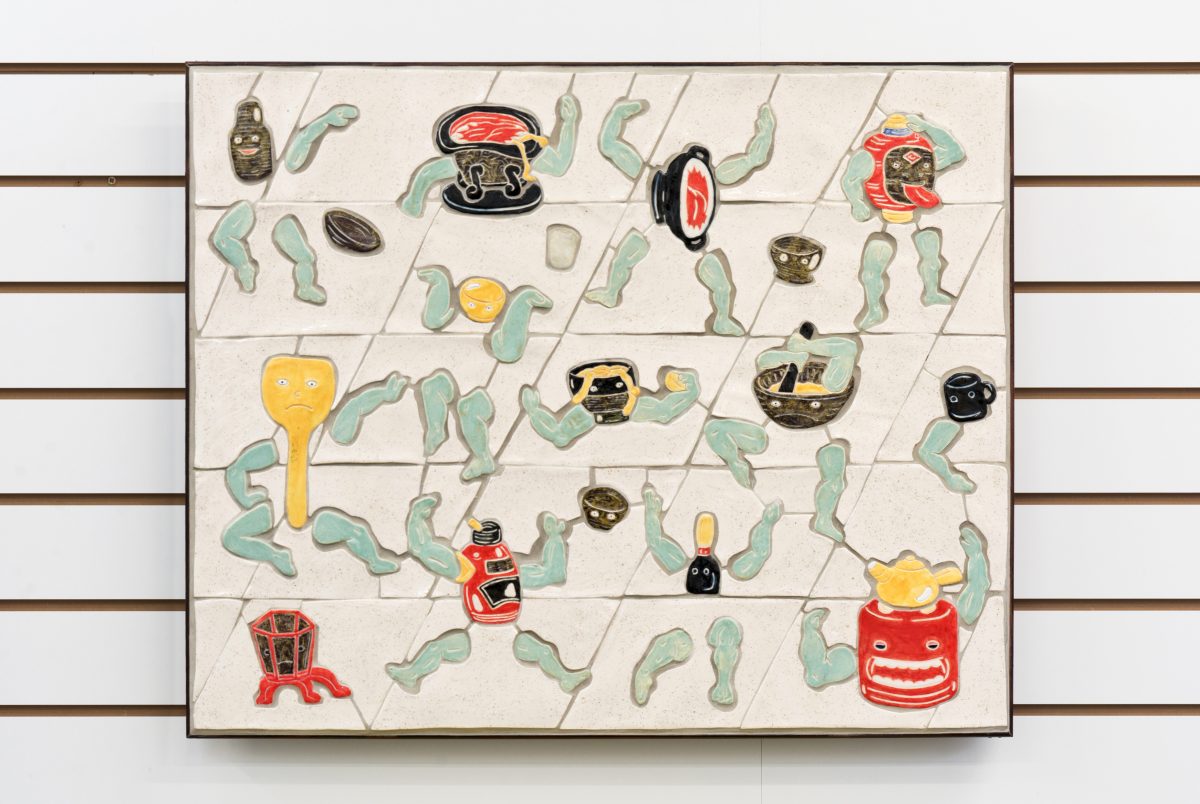

Echoing these scenarios, Fountain of Youth’s robot cult has mistakenly deified coffee cups as a symbol for rebirth. The result is a room of ambitious, multi-textured sculptural works interspersed with coffee cups, pencils and wires, grounding Chin’s speculative fictions in a familiar reality.

Your work moves between Pop Art-like references and a more obscure idiom. How do you view this relationship?

I never really think about or use pop art as a reference when I’m making work, but I can understand the comparison. My work often incorporates food or mundane household objects, usually because they are part of some narrative I’ve built around the show: I see them like props on a stage set, integral components of the scene awaiting their moment.

For this exhibition the relationship is about pairing everyday objects with high-tech devices. I like to watch videos of domestic robots doing mundane tasks badly: there’s something about the juxtaposition of watching something so engineered, with thousands of pounds worth of research invested into it, cleaning a toilet really slowly or attempting to fold clothes or something. Rather than emphasising the banality of the objects, the objects are giving banality to the robots.

Nothing has the label ‘high-tech’ for very long. I think by making these robots seem banal, it places the work in a time period that is undefined, but somewhere slightly beyond the present, where they’ve become ‘part of the furniture’ on the same level as the rest of the objects.

Can you talk through some of your research on transhumanism and technology?

One of the fundamental beliefs in transhumanism is that humans can (and should) merge with technology in order to live forever. I’m really interested in this total undying faith in technology, wanting to both think like and physically become a machine.

“I like to watch videos of domestic robots doing mundane tasks badly”

At the extremities of the movement, there are transhumanists in Silicon Valley performing basement surgeries on themselves, implanting chips under the skin so that they can open the garage door, or control a thermostat with their fingers. I think it’s these big mismatches that I find the most interesting: the contrast in the horror of performing self-inflicted surgery and the banality of the tasks it facilitates makes me think again of those videos of cutting-edge domestic robots performing mundane tasks.

There’s a projection that if you can make it to the age of 120 then you’ll be able to live forever, because the technology to do so will be around by then. I got interested in the idea that if you want and believe that you’re going to live forever, then the present would come to feel like a kind of purgatory.

Following that, is there a didactic element to your works, or are they purely exploratory?

I’m not really sure if there’s anything in particular I want people to take away from this. I start making things with a vague idea in mind and then very much get lost in that process.

The set-up of the show indicates it as a warning of some kind. The red lighting is like some dystopian industrial alarm, or video game death. Or like in bad robot films where the robot turns bad and its eyes go red; I don’t necessarily want people to think my robots are evil, but it may be more to just immediately set the scene as a malfunction.

“I’m really interested in this total undying faith in technology, wanting to both think like and physically become a machine”

I’m interested in the feelings of horror and humour we have towards technology malfunctioning. There’s a horror element to this: when technology glitches it becomes haunting. There’s a bit in Nick Bostrum’s book Superintelligence where he imagines a potential AI catastrophe: a paper clip company tells an AI system to make as many paper clips as possible, and then the AI takes over the entire world. We find this story humorous and horrifying: horrifying in its warning about the impact of using machines we don’t understand; and humorous because of the banality of paper clips and the humongous significance of a seemingly insignificant task.

What was the first piece of art to have a profound impact on you, and why?

When I was seven, my mum took me to the National Gallery and I saw this painting of a horse by George Stubbs and thought it was amazing. I don’t even like horses that much (and I’ve never revisited or had any interest in George Stubbs’ work or horses), but there was something about that horse. I think it’s because it looked so silky and I liked the contrast between the texture of the horse and the plain block colour background: it sort of looked like a big sticker.

Tell us an artist or photographer who you think should be better known.

Taro Izumi is one of my absolute favourite artists. He’s massive in Japan and very well known, but I don’t think he’s ever done a UK show. I first saw his work at a huge installation at Palais de Tokyo in Paris and then got to do a travel scholarship to Japan in 2019 and I saw his piece Cheese and Steak House in 2019. His work mixes sculpture and performance, and it’s always full of play and humour and absurdities.

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant