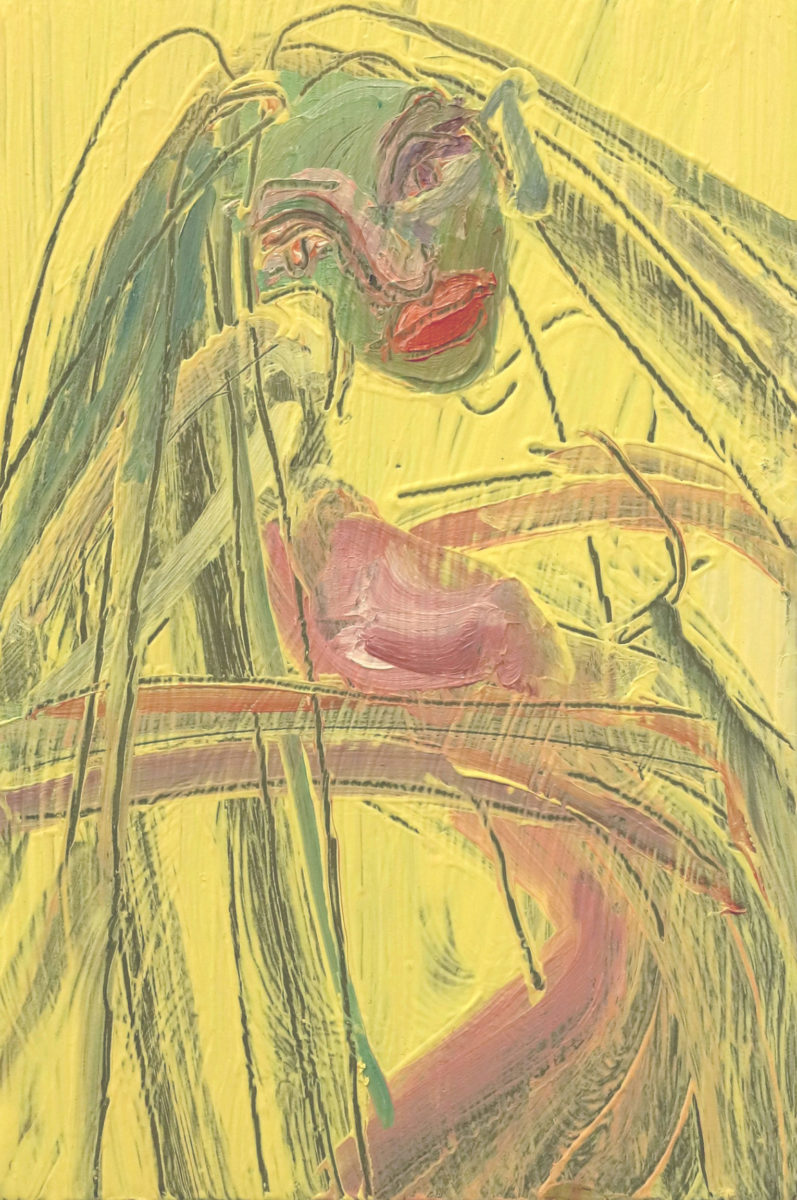

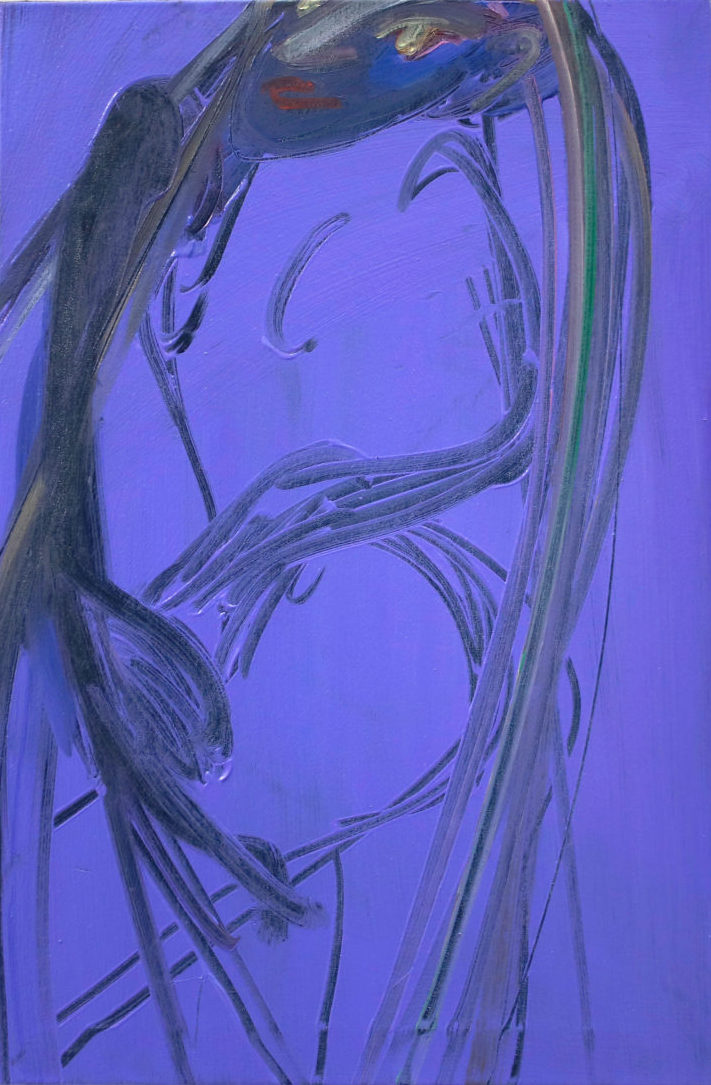

’s paintings, long-haired figures flicker from within the paint. They crouch in deep red to get their legs in-frame, or pose in sugary yellow, with backs turned and a sly over-shoulder look. Bodies give way to their surroundings as Schindler’s line breaks or melts away, but heavy-lidded eyes often remain, gazing or glaring back at you. These figures “opened up a way of dealing with internal contradicting tensions in relation to how women are represented in culture in general and in art especially,” the painter tells me. “I like to think of them as timeless, boundless primeval or modern female creatures, not being depicted but ‘being’ the painting themselves.”

“I’m thinking about subtraction and the act of removing wet paint from the surface, perhaps as a way of manipulating a negative into a positive”

Schindler works into glossy layers of oil paint with a gesture that’s both sharp and fluid. “Subtraction and the act of removing wet paint from the surface is also something I’m thinking about, perhaps as a way of manipulating a negative into a positive,” she explains, a process that speaks to her interest in concepts of desire. “I like that idea that love always comes with a silly pang of pain. That desire is forever rooted in an amorphous unfulfillable lack,” she says. Her painting Limb-Loosener takes its name from the work of Greek poet Sappho, which was translated by Anne Carson in the book Eros the Bittersweet. “Like a memory of a past lover’s face or a familiar scent, these two words lingered with me for a while so I thought it would make a good title,” she says. Within the work, a figure emerges from a collection of curves layered like a multiple exposure photograph.

- Left: Strawberry Moon. Right: Nite Mirror

Carson’s book deals with Eros as it was conceived in ancient Greece, bound up with lack, but Schindler also cites fluidity and multiplicity in language related to the feminine as an interest—specifically within the work of French philosophers Luce Irigaray and Hélèn Cixous.

“Painting, like desire, is also always rooted in a lack. It is not real, never complete. Full of contradictions and questions unanswered”

“I also have this endless visual archive of pictures that I take and that I save from films or from the internet,” says Schindler. “It has many images of Ancient Mesopotamian-Semitic and Hebrew goddesses figurines (Ishtar, Asherah Anat), sort of old-erotica photographs from the 1920s to 1950s that I’ve recently discovered (Atelier Manassé, Carlo Molino) and many figurative paintings (lots of Courbet, Munch, Balthus and the great Leonor Fini).” Histories of imaged women layer up on Schindler’s canvasses, and yet they seem less calcified than totally liquid, slipping from recognition with a wink. “Painting, like desire, is also always rooted in a lack,” she says. “It is not real, never complete. Full of contradictions and questions unanswered.”