Arriving in Marseille, the temperature is a sweet 30 degrees; not a cloud in sight. As our shuttle bus rumbles down the motorway toward the city, I take out my new fan from the welcome gift bag to try to alleviate the heat. Its design says “Art-O-Rama, cooler than ever”—a confident statement—but, between the fair programming, the off-site exhibitions, and the deliciously chilled atmosphere of the city, it really holds up. The exhibition centres and cultural spaces have a gritty urban feel to them–a range of raw, graffiti-scrawled brick buildings with exposed metal beams.

As the autumn art world calendar fills with an increasing number of fairs, the once-sacred August has been reinvented as an opportunity to grab collectors and art enthusiasts on the tail end of their holidays, riding the wave of relaxed positivity induced by a month’s break. Art-O-Rama, now in its eleventh edition, brings together a selection of galleries renowned for their avant-garde programming. They congregate at the Friche Belle de Mai–previously a tobacco factory and still holding on to its industrial charm. The building’s maze-like format encourages exploration—whilst wandering through on your way to the fair, it’s likely you’ll see families playing together outside, teenagers whizzing up ramps on BMXs, luxe little cafes selling gourmet ice lollies under festoon lighting, curated bookshops, artist studios, and the offices of the fair itself. There’s a real sense of community and celebration here, a welcoming charm that is absent from bigger, global superstar fairs.

The calibre of the galleries is high, too—largely European (eleven out of twenty-six from France: ten Paris, one Marseille) with a welcome injection of LA-panache from Ghebaly Gallery (presenting a group booth featuring a fantastically playful animal ceramic by Candice Lin) and Ltd Los Angeles.

Below are the gallery booths that really shone.

KLEMM’S

Fiona Mackay and Émilie Pitoiset were introduced earlier this year by the gallery owners, Sebastien Klemm and Silvia Bonsiepe. They admit, candidly, that when they first talked via email they thought there might be tensions working on the project—an “I’ll take one side of the booth, you take the other” approach—but as soon as they met in person they immediately hit it off and developed a close working relationship, influencing one another and synthesising their subjects as they worked. Their pieces are a quite significant departure from their existing body of work and were kept hidden from Klemm and Bonsiepe until their arrival at the fair. “We were really nervous about what they’d think,” Fiona told me with a cheeky grin on her face. Speaking to Klemm, it is clear he is absolutely thrilled with what they’ve produced.

A striking feature of the booth is the gallery’s logo printed in large-scale letters against the back wall–a move conceived by the artists. On meeting Scottish painter Fiona Mackay, I was struck by her wonderfully colourful character–her vibrant and playful paintings matched it to perfection. Her works evoke sexuality and the aroused body (she was reading Henry Miller while producing them) and she uses lots of warming pink and red tones and curvaceous contours which culminate in a strikingly honest and vibrant aesthetic.

On the other side of the booth are sculptures by Émilie Pitoiset. She has created emotive and lifelike figures out of metal roads, draped in temporally unspecified clothing which manage to at once invoke evening wear, equestrian riding suits and a uniform from a communist alternate reality. One figure sits forlornly on a table, head hung low, staring at its metal hands in a state of what appears to be quite destitute reflection (haven’t we all been there?). Another sits sprawled across a low-lying podium, draped in black, its limbs awkwardly at odds with its body. Her work features the recurring motif of a glove, an image bubbling with the idea of sexual fantasy and domination.

bombon

A huge polystyrene rock presides over bombon’s booth, coated in thick brown paint which gives it a meteor-like quality. In Spain, there’s a tradition around the laying of the first rock when an important building is being constructed–it’s often used by politicians for photo-ops and PR ops. Jordi Mitjà uses this garishly over-sized sculpture to throw shade on politicians for their shameless attempts at self-aggrandisement.

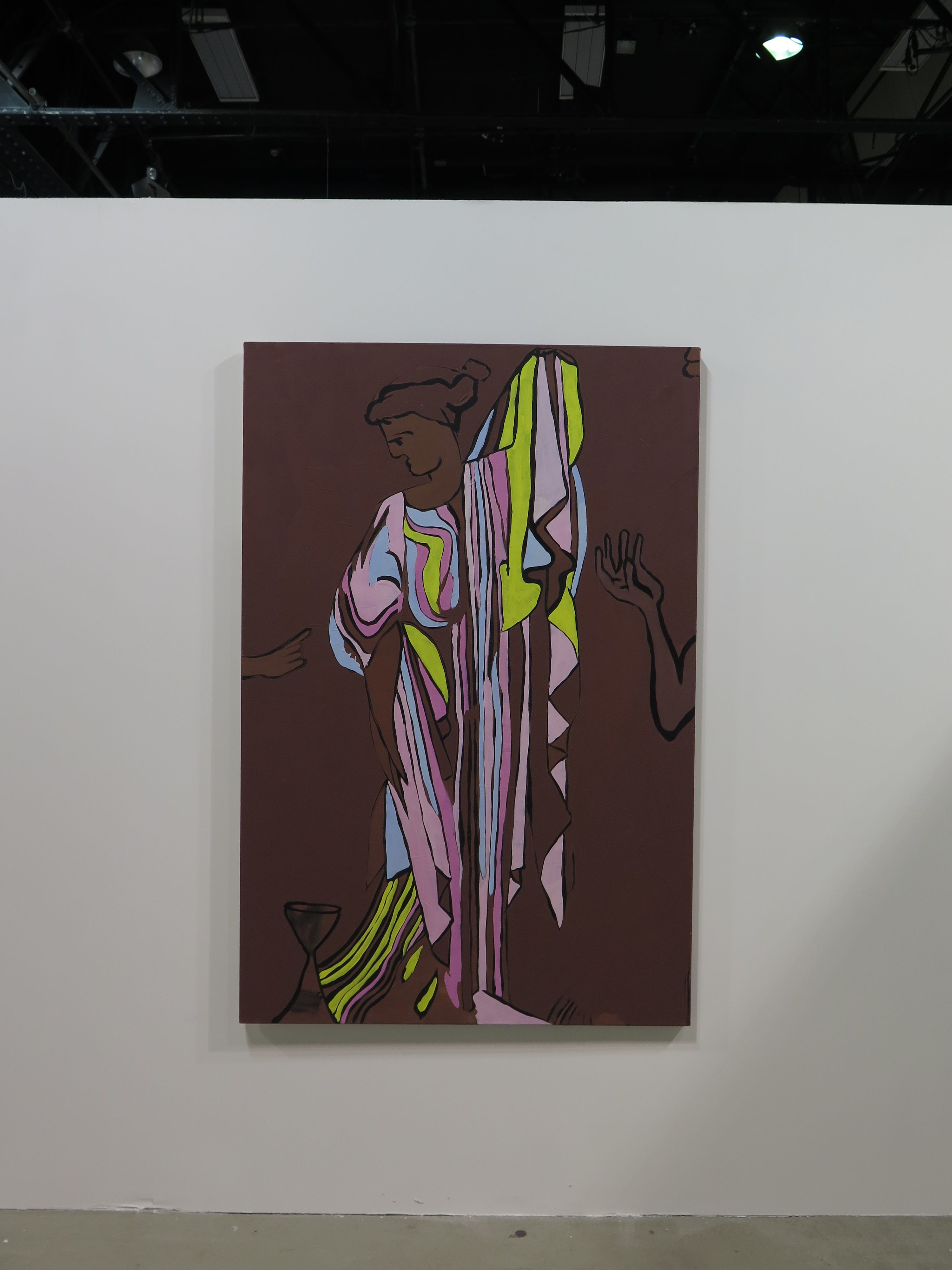

Marguax Valengin’s paintings are exhibited alongside. One large, brown canvas depicts a majestic Greek goddess. A coarse brown background is set against the bright, pastel colours of the figure’s robes and an hourglass sits in the foreground. Two hands and a pair of lips protrude from the outer border of the canvas, hinting at an unknown narrative that informs the static scene. Mythology functions as symbolism in Valengin’s work, as she sees in it the power to stir her viewers’ collective conscience, and tap into a shared tapestry of ideas and emotions. Mitja’s rock also has a mythological quality, imposing over the whole exhibition in an awesome, almost frightening way.

Meessen de Clercq

Jan de Clercq’s fascination with literature is palpable in this collection of international artworks. Clercq proudly admits that he takes to bed early each night to sit with his latest book, and that once he likes an author he will try to read their entire works. The artists he exhibits evidently share his passion.

Jorge Méndez Blake’s sculpture From an Unfinished Work (Stephen Hero) presents aluminium lacquer copies of a single page from one of James Joyce’s unfinished texts as if they had been crumpled up and thrown on the floor. The work is a striking tension between laborious artistic creation and the whimsical act of throwing away which speaks to a gulf between the aims and meaning of the writer and the reception of the reader. This tension is enforced by the disconnect between the apparently laissez-faire act of “crumpling” and the arduous work of “sculpting” such artefacts. The pages’ narrative is impossible to decipher (you have to bend down to try to catch the words, and it is impossible to read more than a few in sequence) hinting at the often unobtainable nature of the language and famously difficult Modernist style of Joyce’s writing.

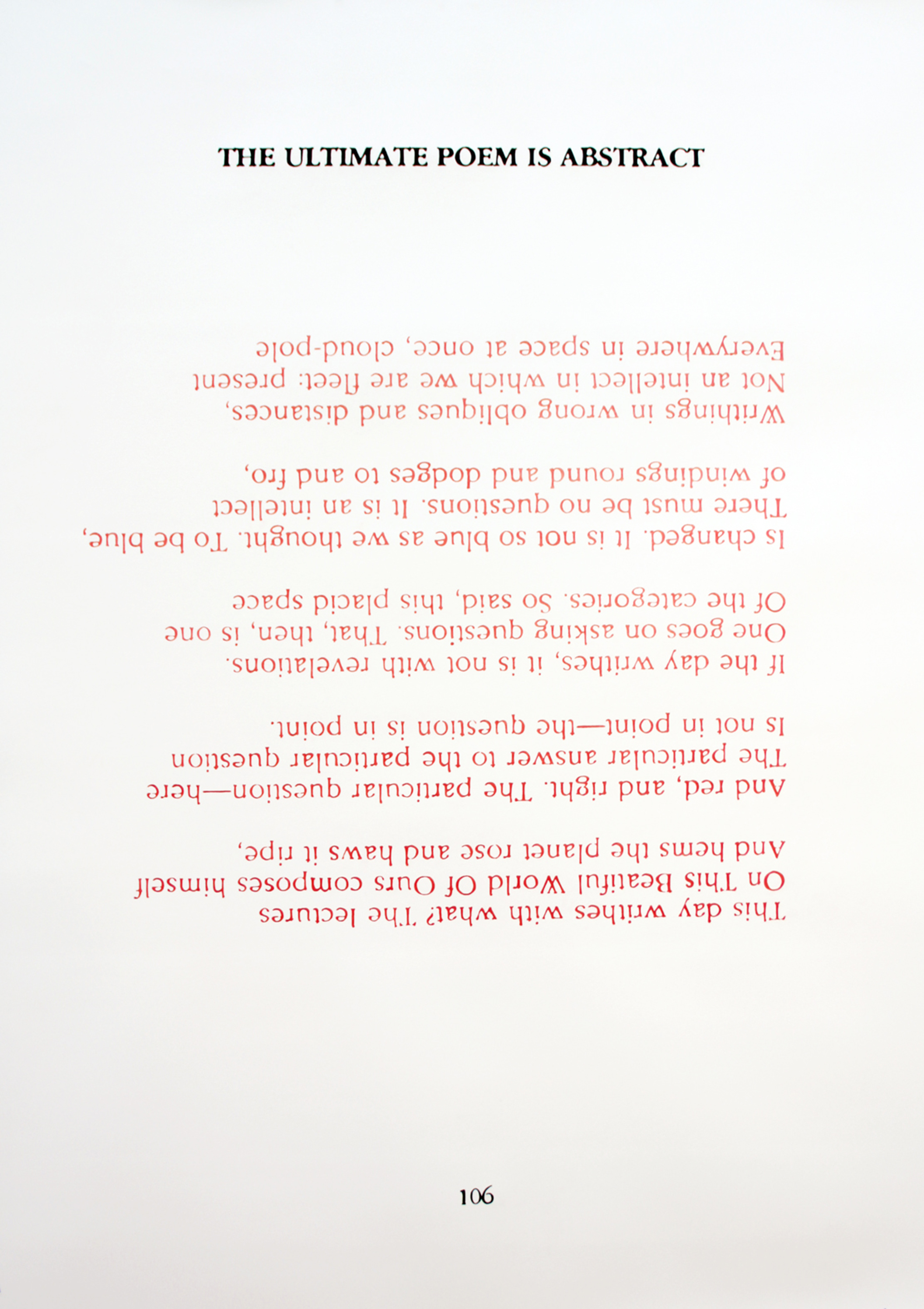

Another of Blake’s works, Ultimate Poem, presents Wallace Steven’s “The Ultimate Poem is Abstract”, drawn upside down in red pencil–(“and red, and right”, reads one line of the poem). Again, Blake seems to play with how form affects the intelligibility of the written word by adding an added layer of impenetrability to a poem of which the meaning is already illusive. Steven’s poem emphasizes the importance of the poem as a place of questions as opposed to answers. By physically turning the poem on its head, Blake makes working out what is contained within the lines a continuous challenge (what is this upside down word, what is the next, and so on) throughout the act of reading. “So said, this placid space – is changed,” reads one line in the poem, and Blake has certainly changed the space.

Margaux Valengin, ‘Villegiature’ (2016). Courtesy the artist and bombon, Barcelona.