Sitting in the garden of Raqib Shaw’s studio, it feels like Christmas day. An assistant has just handed the excited painter a tightly wrapped parcel from Germany. Shaw wields a pair of long scissors, scything through to reveal a bronze ornament. It is a Japanese Meiji-period sculpture of two birds, bought for his upstairs studio. Brown paper lies around our feet as he inspects it. “They have real personality,” he says, before explaining his preference for Japanese art. “They believe that it is the soul of the maker that goes into an object. That is what makes it divine.”

I am visiting Shaw at his home and studio in a former sausage factory in Peckham, South London. He is due to fly to Venice in a few days, not to further examine his show Palazzo della Memoria at the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Ca’ Pesaro, but because he has been summoned for dinner by a collector. I sense he would rather stay at home, tending to his Bonsais and Kashmiri Chinar trees.

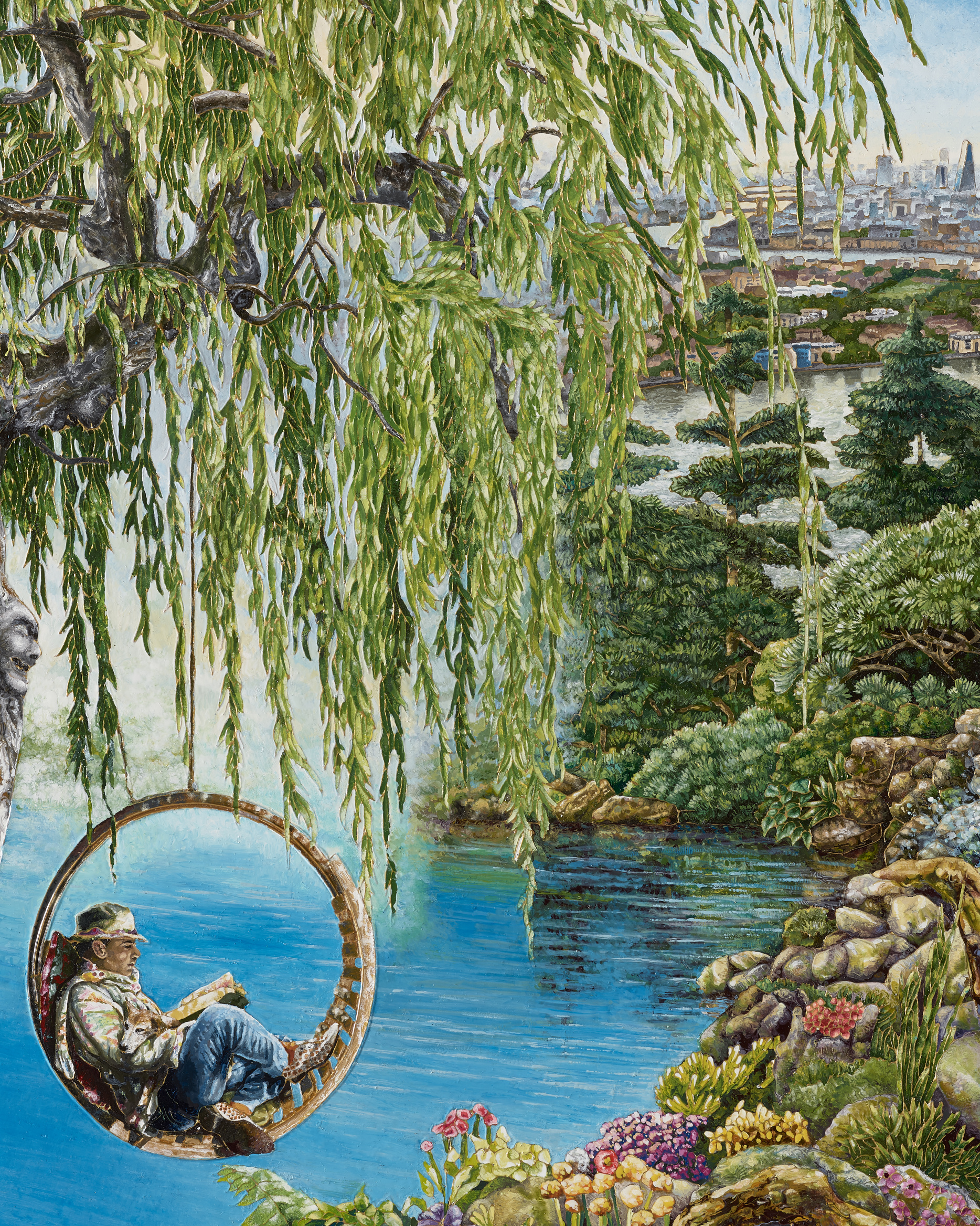

Palazzo della Memoria is one of the rare occasions he feels his paintings have really clicked. In 12 new works, he draws on Venetian masters Tintoretto and Giorgione to create dizzying self-reflexive visions: of his garden, Kashmiri mountain-scapes and palatial fantasylands. The scenes are meticulously etched in acrylic liner before being painted with enamel, on board or aluminium. The effect is of visual abundance, a craft hedonism which reveals darker episodes from his own past.

Raqib Shaw, Summer Solitude I, 2021 © Raqib Shaw

Shaw has lived in the factory (he calls it an atelier, but compound, studio, home and parallel universe also work) for nearly 15 years. “I bought this because it reminded me of a Rajasthani Haveli: a centre courtyard and then these ascending balconies,” he says. After graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2002, he squatted in Percy Dalton’s Peanut Factory in Hackney Wick before moving into a flat owned by fellow painter Peter Doig on Wharf Road, Islington, next to Victoria Miro gallery. A director at the gallery spotted his graduate show and propelled him to rapid success. He hasn’t looked back since.

“I bought this because it reminded me of a Rajasthani Haveli: a centre courtyard and then these ascending balconies”

The Peckham factory was in a state of disrepair when Shaw first saw it, but the heavy machinery gave him hope it could withstand the demands of a vast painting operation. “Everyone thought it was another one of my drunken ideas, buying this place,” he says, “But no! I was completely compos mentis.” Friends expressed concerns about crime in the area, but Shaw ignored them. His Muslim family left Kashmir in 1989 to escape violence between the Hindu and Pandit populations, and he refused to be dissuaded from South London by scaremongering (besides, he rarely actually ventures outside).

- A swing that has appeared frequently in his paintings hangs in the garden (left). Shaw prunes flowers on a summer afternoon (right). Photo: Louise Benson

Gentrification quickly followed, though Camberwell College of Arts still stands nearby, and South London Gallery have moved in next door, taking over the Peckham Road Fire Station. Shaw remembers firemen leaping over the wall when he set his studio alight in an incident involving a candle and dried hydrangeas. A hellish translation of the scene features in When the Thing with Feathers Turned Red (After Tintoretto) (2022), with Shaw depicted surrounded by orange flames, watering can in hand.

“As a painter, you have to completely eradicate that sense of ownership. Works are there to inspire, for people to look at”

His own plan to slow local property developers involves planting a giant sequoia tree in his front courtyard, towering over the Japanese garden he built during lockdown. By feeding it a “Big Mac diet” of Bonsai feed, the roots will stretch far under the factory (the plot currently has planning permission for 42 two-bed flats). “In about ten years, it’ll be double the size of this building and then in comes English Heritage!” he cackles.

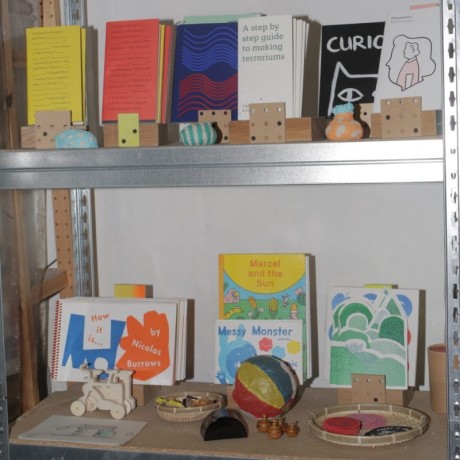

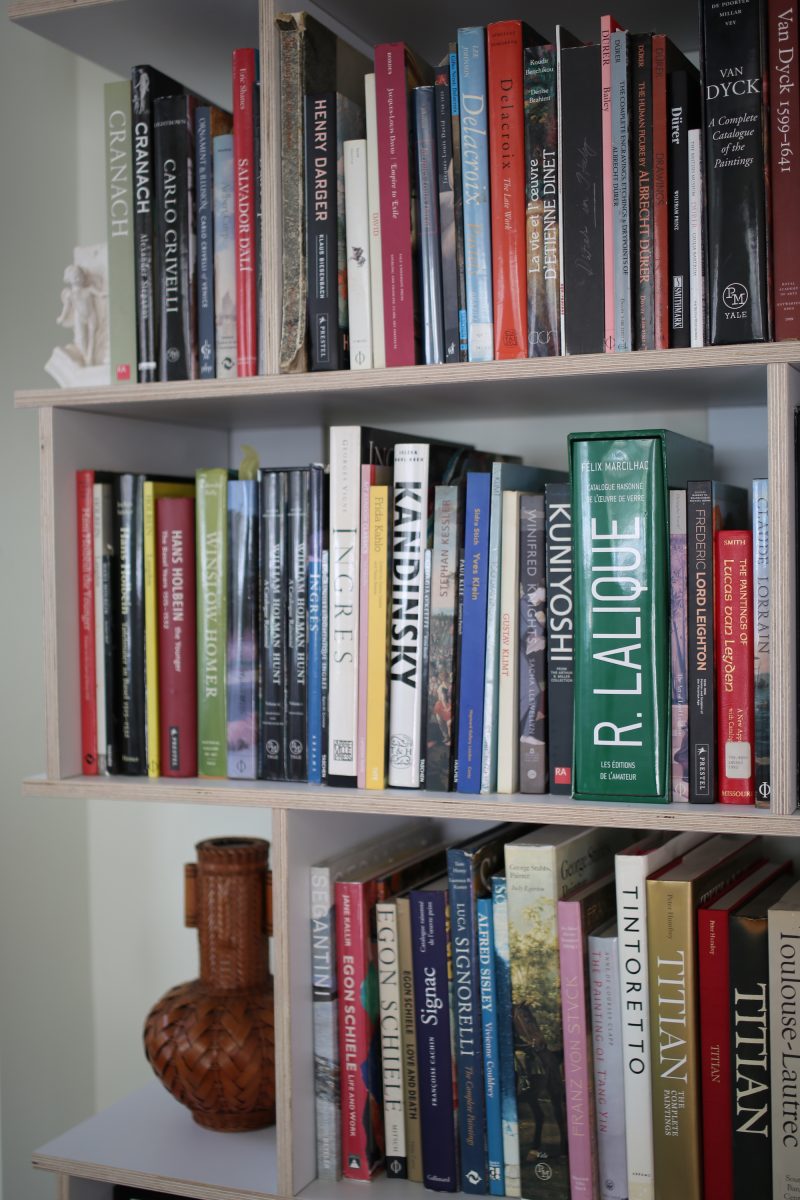

- Bookshelves in one of the reception rooms (left). A table decoration in an adjoining room where Shaw received visitors and has staged parties (right). Photo: Louise Benson

Today, the atmosphere is serene, doors thrown open as assistants paint quietly upstairs. It feels like Eden, but instead of apples we gorge on macarons. There are some grass snakes around, but Shaw seems unconcerned. His own Paradise Lost paintings took him ten years to complete, and he describes the bejewelled, cherry blossom panels as “a personal diary of my life.” He gestures to the garden ponds, rendered as enchanted ravines in Palazzo della Memoria. He feeds his fish impatiently, using a broom handle to swirl them towards the feed. He then pushes me on his wooden swing, which hangs from a tree, and which appears in Summer Solitude

(I and II).

Shaw’s studio hasn’t always been this tranquil. After opera performances staged in the garden, it became a hectic place filled with art-world hangers on. “I got sick and tired of late nights and drinking,” he says. We remain appropriately teetotal today, drinking alphonso mango smoothies made from fruit a friend brought back from India. Shaw insists on making them himself, making a quip about their carbon footprint.

Plants clearly occupy an essential part of Shaw’s life and psyche, but they have now taken on a more pronounced healing role. Shaw’s beloved dogs died in quick succession over the last two years, and a cousin was killed in a car crash in Dubai, an event depicted in miniature in Agony in the Garden (After Tintoretto) II. “Plants offer unbelievable solace, especially in times of loss and great sorrow,” Shaw reflects. He was shocked at the depth of his grief: “One day you wake up and realise you have absolutely no-one close to you in this world,” he says. He speaks not with self-pity, but hard-earned wisdom.

Shaw has a fierce sense of duty to his art, pets and plants. He missed his own show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2009, preferring to stay in London to look after his dogs. But he is most philosophical about his bonsai collection. “You are there to look after them, and you have to pass them onto someone who is going to spend their lifetime doing the same,” he says. “They are the result of many people’s dedication.”

- The bonsai garden, where Shaw cares for over a hundred trees (left). A weeping willow forms the centrepiece of the main garden (right). Photo: Louise Benson

I think of his works-in-progress laying flat in the upstairs studio, being attended by assistants who have been by his side for over a decade. “As a painter, you have to completely eradicate that sense of ownership,” he reflects. “Works are there to inspire, for people to look at.” Ultimately Shaw hopes that his works will all end up in public institutions, rather than private collections. “All collectors eventually succumb to the three Ds,” he says wryly. “Divorce, debt and death.”

“All collectors eventually succumb to the three Ds: divorce, debt and death”

Above all else, Shaw is a classicist, a highly allusive and canon-conscious artist. “The more you look, the more you find,” he says of Palazzo della Memoria. Milton, Bosch, Holbein, Ovid, all the way to the Indian myths he grew up with. But Shaw is there throughout, crouching in the corner of his scenes, tending carefully to the mystical gardens of his own imagination. As we sit on the bench looking out at the real thing, he jolts suddenly, launching into lines from Macbeth. “Life’s but a walking shadow… a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant

Raqib Shaw: Palazzo della Memoria is at the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Ca’ Pesaro, until 25 September 2022