“I think it’s very necessary that black and white women deal with the creative uses of differences between us, and how they can move us towards the things we share. I think it’s imperative also that women of colour continue this work within our communities, as well as white women dealing with this in your own communities”, Audre Lorde stated in an 1982 interview with Blanche Cook. How might this apply in a contemporary art context?

An urgent concern for feminism’s so-called fourth wave has been to examine the whiteness of the dominant rhetoric in the movement; in contemporary art, as much as every area of culture, there is a consistent need to rewrite the false narrative of feminism as western and white-centric within western institutions and art history, by engaging critically with the representations of women artists.

What of the white female gaze on black bodies? In contemporary portraiture, black subjects have continued to be portrayed by white women artists in the west, under the guise of intersectionality. The position of white women artists who chose black subjects is not the same as that of white male artists, when the position of white women and white men is not the same in the world. The experience of being a woman is often related to the experience of the “other”, but that doesn’t mean the white female gaze is free of its inherited past and its privilege in the present. To what extent is that gaze complicit with the subject, and to what extent does it conform to a kind of objectification? How can we discern the intent in the work itself?

“To what extent is the white gaze complicit with the subject, and to what extent does it conform to a kind of objectification? “

Alice Neel, who was perhaps the most prominent white woman artist to paint black subjects, a large and important part of her oeuvre, has been celebrated for her portraits of her neighbours in Harlem. These were predominantly people of colour to whom she felt deeply connected, emotionally and physically, as part of the community that she belonged to and lived in. As Jason Farago wrote in the New York Times of Neel, Neel’s portraits were different because they didn’t seek to explain through social realism. “They were something else: efforts to afford the same status and consideration to her neighbors that earlier portraitists reserved for popes and princes.”

As a white woman in Harlem at the time, Neel’s daily experience would have been very different from that of her subjects. But as a woman, an “other”, an affinity with her subjects is implied, and that can be perceived through her paintings.

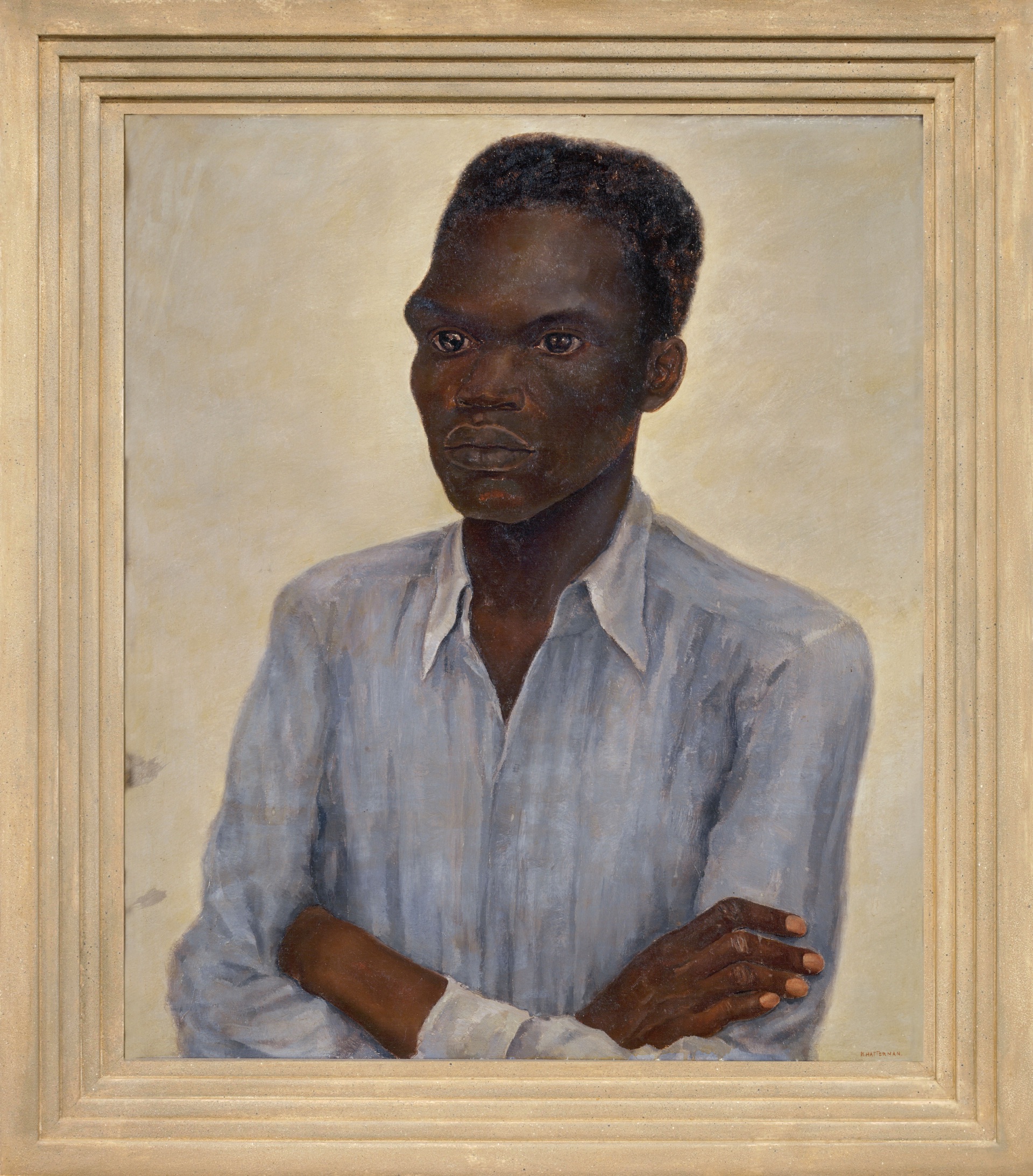

Nola Hatterman was a contemporary of Neel. A little-known Dutch painter, she was born in 1899 into a wealthy colonial family, and her father worked for an import-export company for Dutch East Indies colonial produce. Early on, due to her father’s profession, Hatterman witnessed racism and discrimination against the colonized. “I come from a colonial environment—that was actually the cause of my rebellion”, Hatterman herself explained.

Hatterman became a supporter of Surinamese independence, getting involved in the anti-fascist Surinamese labour movement with the first Surinamese anti-colonialists during the Second World War, doing illustrations for political publications. In 1953 she emigrated to Suriname, where she became the director of the School of van Beeldende Kunst, School of Fine Arts, in Paramaribo, and remained until her death in 1984. Her paintings almost exclusively portray black subjects.

Hatterman’s work, and her use of black subjects, were frequently questioned and critiqued; despite her political intent and commitment, her position was also undeniably problematic. She explained her own preference for black subjects in an interview:

Hatterman’s works and her legacy and role in training a new generation of artists in Suriname, both criticized and celebrated, are explored in an exhibition at the Stedelijk that opens this September. Hatterman’s portraits do appear to actively resist the exoticization and eroticization of blackness, and work against the stereotypical representations of painters of her day. At the same time, her position of power as a white woman in a colonised nation—Suriname only became fully independent from Holland in 1975—can’t be ignored.

Currently also showing at the Stedelijk is a work by the white Dutch artist Dana Lixenberg that is also focused on black subjects: Imperial Courts (2015). The three-channel video installation is an ambitious work that relates to Lixenberg’s portrait series on the inhabitants of the public housing project in Los Angeles that she began to shoot in 1993. Lixenberg first visited Imperial Courts to photograph in the aftermath of the riots in Los Angeles; her position is one of an outsider in every sense. She has explained her own stance as one of respect and empathy; she didn’t try to sensationalize the people she met as the media had done.

“Notions of power, privilege and history cannot be erased from the white female gaze on black bodies”

The people she photographed, having seen the pictures she took, then started to ask her to come back. She began to return regularly to document the residents, eventually starting to film in 2012. The shift in the medium was significant and, Lixenberg told me, necessary in order to reflect these lives and stories, and to record their reactions to the photographs she had taken almost two decades before. The nature of representation, memory and the meaning of photography is at the core of the work, as the residents reflect and discuss the images and their meaning among themselves. Lixenberg’s role is almost absent from the narrative, mechanical rather than political. The subjects speak for themselves, of themselves.

Notions of power, privilege and history cannot be erased from the white female gaze on black bodies. There is also potential to harness that power, through collaboration: to complicate the gaze, and turn it back on itself, by bringing visibility and prominence. To return to Lorde, who writes in The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle the Masters House, “Revolution is not a one-time event. It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses; for instance, it is learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”