It goes without saying that the art world is a microcosm plagued by ethical dilemmas, and few come more fraught than the legacy of posthumously “discovered” artists. The dead have no part in forming the mythologies that critics, historians or curators attach to their names, and cannot challenge the truisms that come to surround their work—factors that become all the more uncomfortable when applied to self-taught, so-called “outsiders”.

Class is one issue: it is no coincidence that many figures labelled with the term have hailed from humble backgrounds and work in professions far removed from the glamorous gallery scene. Moreover, history has a way of reading their achievements as visionary statements, obscuring the possibility that they might be driven by the same creative urges as more conventional artists.

What, then, should we make of it when we encounter the work of one yet to be acknowledged by the wider world? Take the case of Gerard Dalton, a man who passed away just over eight weeks ago in west London. Before last week, I had never heard his name—but without knowing it, I had been wondering at his work for years.

For over a decade, I have been walking by the canal near Trellick Tower and stopping to stare at a particular sight. Over the water, against an urban landscape dominated by grimy Victorian brick and the faded concrete of 1960s modernist buildings, stands a long stretch of blue-grey wall that spans past the gardens of four houses. Partially hidden by neat topiary and exotic trees, it resembles a kind of shrine, speckled with tiles, trinkets and colourful objects of all forms and sizes, arranged in uneven but rational patterns. From the path, you can just make out some unusual figurative sculptural forms rising about three foot from the ground, their chalk-white plinths lending them a sepulchral air at odds with the general magpie aesthetic.

It could be anything: a relic of the area’s countercultural past (in the 1970s, the neighbourhood had informally been known as “Squatland”); the lair of some eccentric millionaire art collector; perhaps even a voodoo burial ground. All were theories I entertained when passing by over the course of the next ten years, convinced that the story behind it would remain one of those strange, highly visible but entirely private secrets that form part of living in a city.

“Many so-called outsiders have posthumously been exploited for profit, on the strength of visionary myths they have no say in controlling”

Until visiting the house last week, I could never have guessed that Dalton, an immigrant from Ireland who had lived in one of the flats backing onto the canal from 1983 until his death this year, had spent years creating this vision alone. Born to a farming family near Athlone in 1935, Dalton had grown up, in his own words, without “much education really”. Despite a fascination with history that would stay with him his entire life, the academic opportunities available to a farm boy from County Westmeath were limited, and he ended up working as a handyman for Colonel Harry Rice, a rich, retired bon vivant with a taste for landscape gardening.

Dalton gave only one formal interview in his lifetime, with his friend and neighbour Roc Sandford, but he made no secret of his creative debt to his one-time employer: “[Colonel Rice] inspired me, he did really,” he acknowledged. “Because every tree in the world was planted around that house, it was unbelievable.” We can never know for sure, but it is tempting to imagine that his experiences of building a rockery for the colonel might have been the imaginative seed for what would become a life’s work.

Dalton moved to London in 1959, first working in railway sorting offices, then taking on a series of catering jobs around the city. We know little about this long period of his life, and nothing of any creative projects he may have undertaken. But following his retirement in the mid-1990s, something sparked him to begin producing his art at a prodigious rate: from here on in, he devoted himself to turning his garden into a personal museum. He created as many as 115 sculptures of British, Irish and European historical figures, and decorated the barren stretch of waterfront until it became the decorative masterpiece that would catch myself and countless others by surprise.

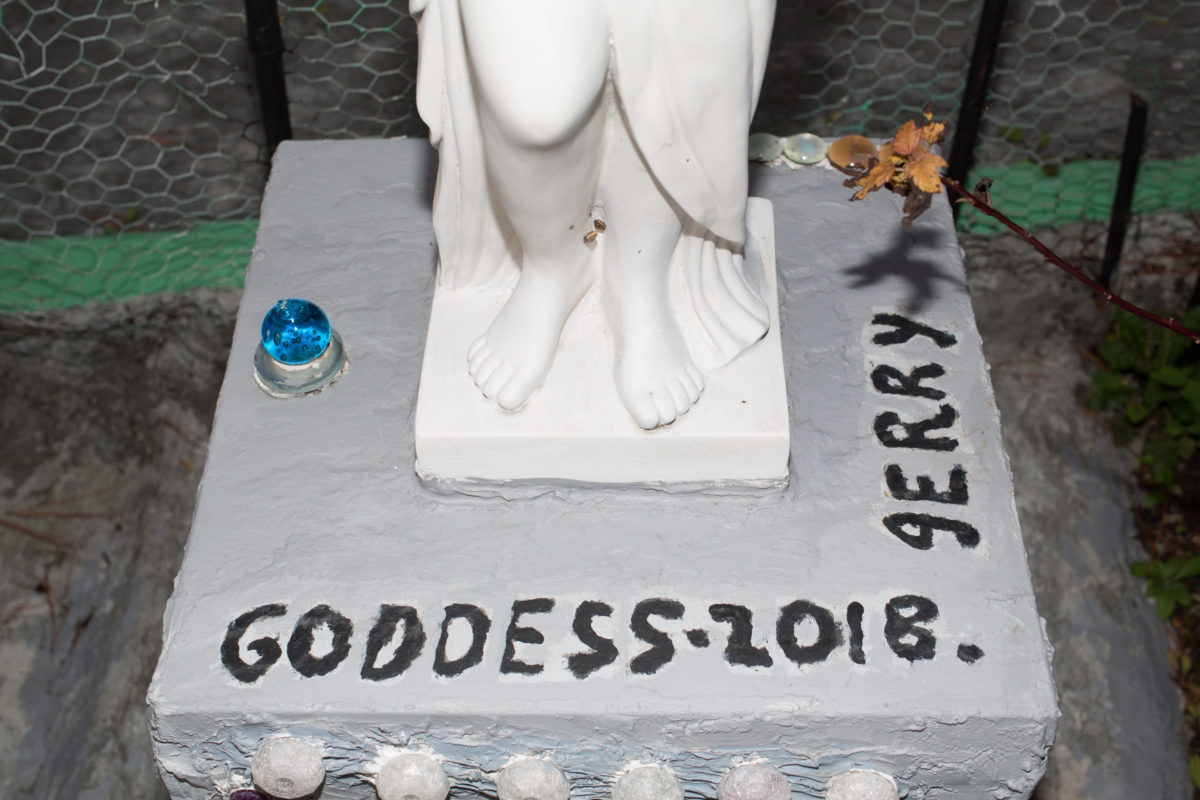

Behind the towpath, he transformed his small, square garden into a miniature sculpture park, its paths lined with statues of subjects including Jonathan Swift, the Irish warrior-queen Maeve, and Napoleon—something of a Dalton obsession; according to him, all were chosen on the democratic basis that they were “brilliant in their ways” (Oliver Cromwell—“a bad guy”—being the exception that made the rule).

Though all these sculptures were fashioned from just a handful of moulds, each individual work contains enough idiosyncratic detail to distinguish it from its neighbour, their clothes and wild hair arrangements all subtly differing, their distinctive, red-rimmed eyes painted to betray startling expressiveness. Others brandish plastic revolvers, or arrangements of brooches and gemstones studded across their bodies in unique configurations.

“I wanted to do a lot of statues [but] I couldn’t do them in the winter with the cold weather”, Dalton explained to Sandford. The temperature may have forced him indoors, but it was no bar to his creativity. Indeed, the interior of his home is, if anything, more arresting than the garden. Even had I been aware of the nature of Dalton’s project before visiting, nothing could have prepared me for the experience of walking into this seemingly modest ground-floor flat. The front room alone contains around a dozen dolls’ house sized replicas of palaces, castles, cathedrals and tower blocks complete with beautiful interior detailing and exquisite handmade furnishings.

Buckingham Palace, the Victoria Monument, St Paul’s Cathedral and Syon House were all there, created from wood, papier-mâché, card and whatever other found objects—matches, birthday cake candles, plastic gemstones—that came to hand. The attention to detail is astonishing. His Westminster Abbey, for example, includes everything from miniature tombs to stained glass windows fashioned from translucent plastic, while a vast replica of Hampton Court Palace apparently made with just a hammer, a chisel and a saw (“all the tools I had,” Dalton recounted) even finds space for a lonely visitor bench.

Almost every inch of space is put to creative use. The shelves are crammed full of figurines and plastic busts repurposed to represent his heroes, each repainted and labelled to create a very personal pantheon. On the walls hang hundreds of collages constructed from reproductions of historical paintings, as well as dozens of paintings and prints embellished with broad strokes of psychedelically bright paint; though Dalton clearly wasn’t much of a hippie, his home is full of evocations of 1960s counterculture. Whether or not this was intentional, it’s impossible to say: while Dalton was clearly an appreciator of Classical and Renaissance art, eighteenth and nineteenth century portraiture and history painting, we have no idea if he was concerned with or even much aware of modernism and its attendant theories.

“With London’s severe shortage of affordable housing, transforming a habitable apartment into a cultural venue is both a commercial hard sell and an ethical dilemma”

How, then, are we to treat Dalton’s legacy? Many so-called outsiders have posthumously been exploited for profit, on the strength of visionary myths they have no say in controlling. The obvious and ideal way to prevent this happening to Gerald Dalton, an artist whose life’s work is inextricably linked to the place of its creation, would be to convert his home into a not-for-profit museum.

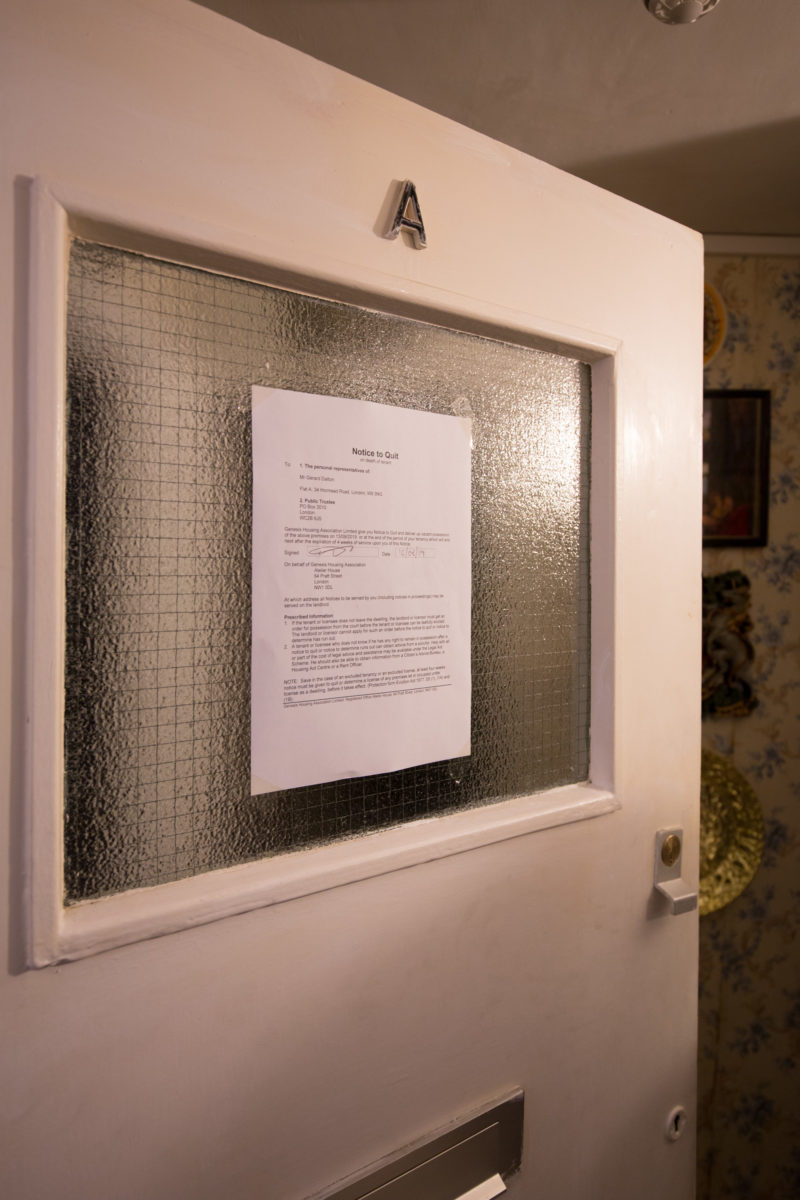

But herein lies a problem, and an urgent one at that. The Housing Association that owns the apartment has the right to repossess the property on the death of the tenant, and with London’s severe shortage of affordable housing, transforming a habitable apartment into a cultural venue is both a commercial hard sell and an ethical dilemma. The only conceivable hope of preserving this otherworldly monument to the imagination may be to buy the property outright.

It will not be easy to raise the funds to do so. “I don’t know of any situation in which ‘outsider art’ created in social housing has survived in Britain,” says the independent curator Sasha Galitzine, a friend of Dalton’s who opened up the house to the public for several weeks in October. Nevertheless, she is spearheading the campaign to preserve his home, and is quietly optimistic. “We’ve had about 400 visitors passing through in the past few weeks, and everyone who has come has been amazed by it,” she says. “This must at least show that this is a place of inspiration that must be preserved.” A Just Giving campaign to turn the flat into a museum has recently been launched.

But over all of this hangs a crucial question: what would Dalton himself have wanted? On this count, he left only one clue as to his hopes and expectations: “They’ll be astonished what they’ll find in my garden in years to come,” he mused. “It’ll be like Pompeii or something—Gerry’s Pompeii.”

All photographs © Miguel Santa Clara